Dante's Divine Comedy: Purgatorio

Canto XXXII

Beatrice descends from the chariot before the Tree of Knowledge. An allegorical scene follows, where the Griffin binds the chariot pole (Christ, the Second Adam) to the tree (the First, fallen Adam) which bursts into bloom (Christ's redemption of mankind). Dante is shown a second allegorical masque, the Pageant of Church and Empire. The Eagle (pagan Rome) attacks the tree (the early Christians) and the appearance of a fox (heresy) precedes that of a dragon (the schism with Islam) tearing through the floor of the chariot (the Church). The broken vehicle sprouts forth several heads (the Beast of the Apocalypse) and a prostitute (the perfidious papacy in Avignon) dallies with a giant (the corrupt French kings).[1]

So steadfast and attentive were mine eyes

In satisfying their decennial thirst,

That all my other senses were extinct,[2]

And upon this side and on that they had

Walls of indifference, so the holy smile

Drew them unto itself with the old net

When forcibly my sight was turned away

Towards my left hand by those goddesses,

Because I heard from them a "Too intently!"

And that condition of the sight which is

In eyes but lately smitten by the sun

Bereft me of my vision some short while;

But to the less when sight re-shaped itself,

I say the less in reference to the greater

Splendor from which perforce I had withdrawn,

I saw upon its right wing wheeled about

The glorious host returning with the sun

And with the sevenfold flames upon their faces.

As underneath its shields, to save itself,

A squadron turns, and with its banner wheels,

Before the whole thereof can change its front,

That soldiery of the celestial kingdom

Which marched in the advance had wholly passed us

Before the chariot had turned its pole.

Then to the wheels the maidens turned themselves,

And the Griffin moved his burden benedight,

But so that not a feather of him fluttered.

The lady fair who drew me through the ford

Followed with Statius and myself the wheel

Which made its orbit with the lesser arc.[3]

So passing through the lofty forest, vacant

By fault of her who in the serpent trusted,

Angelic music made our steps keep time.

Perchance as great a space had in three flights

An arrow loosened from the string o'erpassed,

As we had moved when Beatrice descended.[4]

I heard them murmur altogether, "Adam!"

Then circled they about a tree despoiled

Of blooms and other leafage on each bough.

Its tresses, which so much the more dilate

As higher they ascend, had been by Indians

Among their forests marveled at for height.[5]

"Blessed art thou, O Griffin, who dost not

Pluck with thy beak these branches sweet to taste,

Since appetite by this was turned to evil."[6]

After this fashion round the tree robust

The others shouted; and the twofold creature:

"Thus is preserved the seed of all the just."

And turning to the pole which he had dragged,

He drew it close beneath the widowed bough,

And what was of it unto it left bound.

In the same manner as our trees (when downward

Falls the great light, with that together mingled

Which after the celestial Lasca shines)

Begin to swell, and then renew themselves,

Each one with its own color, ere the Sun

Harness his steeds beneath another star:

Less than of rose and more than violet

A hue disclosing, was renewed the tree

That had erewhile its boughs so desolate.

I never heard, nor here below is sung,

The hymn which afterward that people sang,

Nor did I bear the melody throughout.[7]

Had I the power to paint how fell asleep

Those eyes compassionless, of Syrinx hearing,

Those eyes to which more watching cost so dear,[8]

Even as a painter who from model paints

I would portray how I was lulled asleep;

He may, who well can picture drowsihood.

Therefore I pass to what time I awoke,

And say a splendor rent from me the veil

Of slumber, and a calling: "Rise, what dost thou?"[9]

As to behold the apple-tree in blossom

Which makes the Angels greedy for its fruit,

And keeps perpetual bridals in the Heaven,

Peter and John and James conducted were,

And, overcome, recovered at the word

By which still greater slumbers have been broken,

And saw their school diminished by the loss

Not only of Elias, but of Moses,

And the apparel of their Master changed;

So I revived, and saw that piteous one

Above me standing, who had been conductress

Aforetime of my steps beside the river,

And all in doubt I said, "Where's Beatrice?"

And she: "Behold her seated underneath

The leafage new, upon the root of it.

Behold the company that circles her;

The rest behind the Griffin are ascending

With more melodious song, and more profound."[10]

And if her speech were more diffuse I know not,

Because already in my sight was she

Who from the hearing of aught else had shut me.

Alone she sat upon the very earth,

Left there as guardian of the chariot

Which I had seen the biform monster fasten.

Encircling her, a cloister made themselves

The seven Nymphs, with those lights in their hands

Which are secure from Aquilon and Auster.

"Short while shalt thou be here a forester,

And thou shalt be with me for evermore

A citizen of that Rome where Christ is Roman.[11]

Therefore, for that world's good which liveth ill,

Fix on the car thine eyes, and what thou seest,

Having returned to Earth, take heed thou write."

Thus Beatrice; and I, who at the feet

Of her commandments all devoted was,

My mind and eyes directed where she willed.

Never descended with so swift a motion

Fire from a heavy cloud, when it is raining

From out the region which is most remote,

As I beheld the bird of Jove descend

Down through the tree, rending away the bark,

As well as blossoms and the foliage new,[12]

And he with all his might the chariot smote,

Whereat it reeled, like vessel in a tempest

Tossed by the waves, now starboard and now larboard.[13]

Thereafter saw I leap into the body

Of the triumphal vehicle a Fox,

That seemed unfed with any wholesome food.[14]

But for his hideous sins upbraiding him,

My Lady put him to as swift a flight

As such a fleshless skeleton could bear.

Then by the way that it before had come,

Into the chariot's chest I saw the Eagle

Descend, and leave it feathered with his plumes.[15]

And such as issues from a heart that mourns,

A voice from Heaven there issued, and it said:

"My little bark, how badly art thou freighted!"

Methought, then, that the earth did yawn between

Both wheels, and I saw rise from it a Dragon,

Who through the chariot upward fixed his tail,[16]

And as a wasp that draweth back its sting,

Drawing unto himself his tail malign,

Drew out the floor, and went his way rejoicing.

That which remained behind, even as with grass

A fertile region, with the feathers, offered

Perhaps with pure intention and benign,

Reclothed itself, and with them were reclothed

The pole and both the wheels so speedily,

A sigh doth longer keep the lips apart.

Transfigured thus the holy edifice

Thrust forward heads upon the parts of it,

Three on the pole and one at either corner.

The first were horned like oxen; but the four

Had but a single horn upon the forehead;

A monster such had never yet been seen![17]

Firm as a rock upon a mountain high,

Seated upon it, there appeared to me

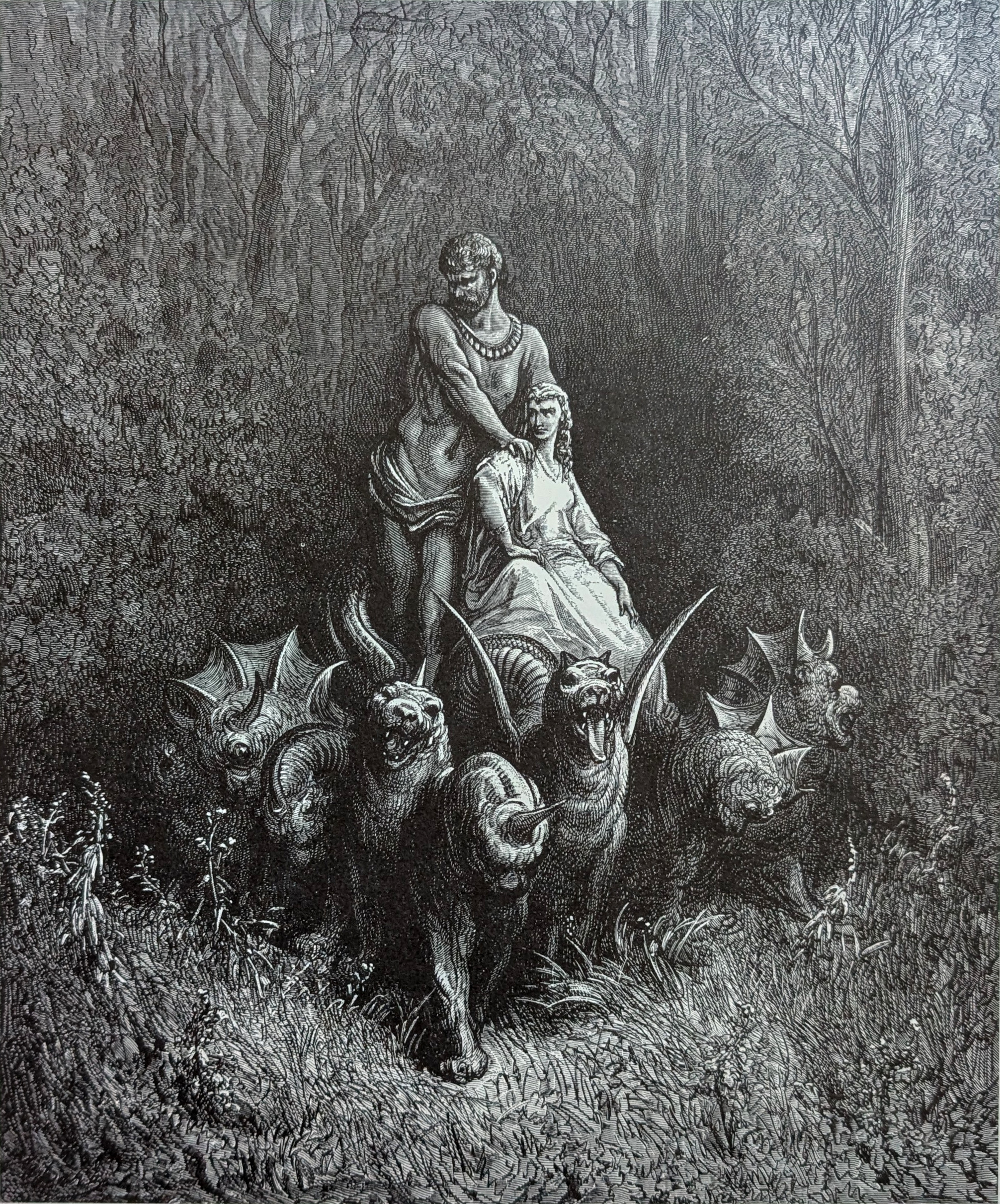

A shameless whore, with eyes swift glancing round,[18]

And, as if not to have her taken from him,

Upright beside her I beheld a giant;

And ever and anon they kissed each other.

But because she her wanton, roving eye

Turned upon me, her angry paramour

Did scourge her from her head unto her feet.

Then full of jealousy, and fierce with wrath,

He loosed the monster, and across the forest

Dragged it so far, he made of that alone

A shield unto the whore and the strange beast.

Illustrations of Purgatorio

Upright beside her I beheld a giant; / And ever and anon they kissed each other. Purg. XXXII, lines 152-153

Footnotes

1. Table:

The Seven Tableaus

1 Tree of Knowledge

2 Fox

3 Eagle

4 Dragon

5 Weeds-Feathers

6 Monster

7 Giant-Whore

2. decennial, Latin decennium, decennis+ium “10-year”+suffix as noun, deciēs+annus+is, “ten times”+“year”+suffix as adjective.

3. As the chariot makes its right turn, the three Theological Virtues and the four Cardinal Virtues turn also (along with Dante, Statius, and Matelda). The griffin, pulling the chariot with Beatrice, also turns. Recall that, unlike other representations of griffins in art and literature, this griffin (representing Christ in his two natures) has great wings. But note how, in all the movement of this great parade, not a single one of its feathers (as part of his divine nature) is ruffled–-a symbol of divine serenity.

4. The procession continues to move slowly through the Earthly Paradise keeping time with heavenly music. Perhaps the angels are still singing. Sadly, though, the forest is empty because of the sin of Eve and Adam. Dante tells us that when the procession stopped they had traveled about three times the distance of an arrow shot. The maximum distance for a medieval longbow was about 300 yards, so everyone stops about 900 yards from where they started.

5. At this point, Beatrice steps off the chariot near a great barren tree, and everyone murmurs “Adam.” With this, we have certainly arrived at the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil which, along with the Tree of Life, is planted at the center of the Earthly Paradise (see Genesis 2:9). It is appropriate, considering the vast consequences of his sin, that at this spot Adam be mentioned in connection with the barren Tree of Knowledge. Furthermore, we are reminded here of the tree below on the Terrace of Gluttony that was an offshoot of this one, and whose branches were arranged like this one to prevent climbing or, more specifically here, God’s command that it’s fruit must not be eaten.

The specific mention of India here is exotic, according to Ronald Martinez, and gives some weight to the traditional notion of Eden as a far away place. The reference to the great height of its trees comes from Virgil’s Georgics (2:112ff).

6. There were legends in Dante’s time that the Cross upon which Jesus was crucified was made from the wood of this tree. In the Golden Legend by Jacobus de Voragine, the chapter on the Life of Adam ends with Seth planting three seeds from which the Tree of the Cross grows: “When Adam was close to death, he sent his son Seth into Paradise to the Tree of Life, also known as the Tree of Mercy, to get from it the oil of mercy that would relieve the dying man of his pains. Seth returned and also brought with him three seeds from the Tree of Life. When Adam died, Seth put the seeds under his father’s tongue and buried him. Later, three great trees grew out of Adam’s grave, and from one of them was hewn the Cross on which Jesus was crucified.”

7. Those gathered around the renewed Tree of Knowledge begin to sing a hymn. That it’s not recognizable because it’s not sung on earth begs the question, of course. What might it have been? And Dante himself is no help here because he fell asleep listening to it! However, Robert Hollander, in his commentary here does quite a bit of literary sleuthing. “We are looking for a song with two characteristics: it must be unknown on earth and it almost certainly must be in celebration of Jesus’ victory over death.” He concludes that the hymn is referenced in the Book of Revelation at the end of the New Testament. In chapter 14:3 we read about the 144,000 who are saved: “They were singing what seemed to be a new hymn before the throne, before the four living creatures and the elders. No one could learn this hymn except the hundred and forty-four thousand who had been ransomed from the earth.” Indeed, there are many hymns in the Book of Revelation for which we have the texts, but not this one. Since this “new hymn” is reserve d only for those who are saved at the end of the world, it is not known by us (Dante) yet.

8. That Dante falls asleep when he hears the heavenly singing is not meant to indicate any rudeness on his part. Quite the opposite. His attention to the music gives him a deep sense of serene peace and tranquility in this place where he has witnessed the symbolic re-flowering of the Tree of Knowledge and the symbolic reconciliation of God and humankind through the Cross. At this moment, one might say, the Earthly Paradise has been restored to its original state for the Pilgrim’s benefit.

The story of Argus from Ovid’s Metamorphoses (I:568-747) is not humorous, but the way Dante uses it here gives one a smirk as we try to picture him painting himself falling asleep! In Ovid’s story, Jupiter fell in love with the beautiful Io and was caught by his wife Juno. She promptly turned the girl into a cow. To keep an eye on the cow (Io), Juno put the hundred-eyed Argus on guard. Not to be outdone, Jupiter sent Mercury to lull Argo to sleep with music or, according to Ovid, by telling stories of Pan and Syrinx. Asleep, Mercury cut his head off, and Juno put the eyes of Argo into the peacock’s tail. Perhaps thinking of a smirk himself, Mark Musa notes here: The tribute to Ovid helps to temper the high seriousness of this interlude on the mountain by suggesting that by imitation, Dante might be putting us to sleep.”

9. A moment ago, Dante had fallen into a deep sleep listening to heavenly music. Jolted awake by a bright light, he finds himself being chided by Matelda. What follows will be another transition point among these many scenes here in the Earthly Paradise.

As though to excuse himself for sleeping, Dante tells a version of the Transfiguration story in St. Luke’s Gospel (9:28-36). Jesus went up a mountain to pray and took along with him Peter, James, and John. While praying, Jesus’ appearance and clothing became dazzlingly bright and he was seen talking with Moses (representing the Law) and Elijah (representing the prophets). The three disciples had fallen asleep earlier, but were now fully awake and saw what was happening. Soon, they were covered by a cloud and heard the voice of God say: “This is my chosen Son, listen to him.” And then they were alone. (By the way, Dante’s sons were named Peter, James, and John. Pietro di Dante was the first to comment and lecture on his father’s work.)

Dante embellishes this story with additional imagery as though he, himself, were one of the apostles. The apple tree is Jesus who is also the host at the eternal banquet where all of heaven celebrates the perpetual marriage feast of Christ and his Church. I n Revelation 19:9 we read: “Blessed are those who have been called to the wedding feast of the Lamb.” The Lamb is an ancient Christian symbol of Jesus as the Lamb of God who was sacrificed for our salvation.

10. A moment ago, Matelda had awakened Dante. He seemed only concerned with Beatrice, and here he seems simply to have dismissed Matelda altogether. Beatrice, on the other hand, has changed. She has left the chariot, and instead of the rather imperious role she played earlier, she is seated on the ground–-a symbol of humility–-under the shade of the Tree of Knowledge. In her new role, surrounded by the seven virtues, she guards the chariot that the griffin (Christ) had tied to the tree. The chariot now represents the Church in the period after the Ascension to the time of Dante.

11. This short speech by Beatrice is completely without introduction, and it contains a wonderful promise. She tells Dante that he will continue to live in the world, and that when he dies he will join her in Paradise.

With this said, however, she tells Dante that he is going to witness a second pageant–-in seven parts-–all focused on the chariot and which depict the struggles of the Church from the time of Christ’s Ascension into Heaven to the present (the year 1300). Lending her own authority to one of the chief goals of the Poem, she wants Dante to watch the pageant very carefully and to write down for the benefit of posterity everything he is about to see.

12. This is the first of the seven tableaux witnessed by Dante. This and the six that follow it are very different from the first pageant where we witnessed, in a highly symbolic parade, the Church Triumphant from the beginning of time to the end of the world. In this second group of scenes, Dante sees the real (non-symbolic) struggles of the Church over the last 1300 years played out as a kind of allegory. Ronald Martinez notes in his commentary that these tribulations “recall the seven plagues of the Apocalypse (Book of Revelation) loosed by the opening of the seven seals” (See Rev. 5-8).

Faster than a powerful bolt of lightning, Dante sees a great eagle (symbolizing the Roman Empire’s persecution of the early Church) fly down into the Tree of Knowledge and ravage it before it slams into the side of the chariot (the Church) causing it to roc k back and forth like a ship (a traditional image of the Church) in a storm.

13. Traditionally, the Church has been referred to as a ship, the ship of St. Peter, the head of the Apostles and the first pope. It is he whose voice is heard from Heaven mourning the Church’s loss of its Gospel simplicity by acquiring wealth and power.

14. In this second of the seven tableaux, an emaciated fox jumps into the chariot. Shouting at it, Beatrice (here symbolizing Theology and Wisdom) causes the hungry creature (symbolizing its hollow doctrine) to flee as fast as it could. This fox with its “foul offenses” represents the early heresies that afflicted the early Church. In the Hebrew Bible, the prophet Ezekiel refers to false prophets as “foxes in the desert” (13:4). In his Narrative on Psalm 80, part 14, St. Augustine writes: “Foxes signify treachery , and especially heretics; deceitful, fraudulent, hiding in cavernous corners and deceiving, smelling foul.”

15. This is the third of the seven tableaux. The eagle of the Empire returns, flies through the Tree of Knowledge again, and this time lands inside the chariot. There it leaves some of its golden feathers symbolizing the Church’s gradual acquisition of wealth and power following the Emperor Constantine’s conversion and the end of the persecution of Christians. However, what was worse was what is known as “The Donation of Constantine.” Accordingly, around the year 315 AD, the Emperor granted Pope Sylvester I control over the western part of the Empire. Dante, of course, considered this action to be the source of many of the evils plaguing the Church in his time. The document was determined to be a forgery in 1439. For more on the Donation of Constantine, see my commentary on Canto 19 of the Inferno, notes 17 and 20.

16. This fourth tableau represents one or more of the schisms that afflicted the Church in its earlier centuries. Most commentators point to Mohammed and the growth of Islam. Recall that Dante places him among the schismatics in Canto 28 of the Inferno. The dragon here breaks the floor of the Church and threatens its unity. This dragon is Satan, featured as a power of great evil in Chapter 12 of the Book of Revelation. In verse 4 we read: “It’s tail swept away a third of the stars in the sky and hurled them d own to the earth.” That the dragon here comes up from below highlights the cleverness and subtlety of the devil’s wiles.

This fifth tableau follows from the third one where, because of its growing wealth and power (royal gifts, privileges, acquisition of lands like the Papal States), the Church (chariot) becomes like a rich soil where weeds grow all over it like feathers. Tho ugh some of these may have been well-intentioned, Dante notes that these “feathers” growing on the Church spread ever so quickly, like a virus, over the entire chariot, even the wheels and the pole.

17. In this sixth tableau Dante sees the chariot of the Church turn into a grotesque monster, the likes of which have never been seen. Already covered with feathers, the chariot starts to sprout heads on various of its parts. Three heads, looking like t he heads of oxen, grow on the pole. Each has two horns. And then one head grows on each of the four corners of the chariot, and these have only one horn on top of their heads. Unfortunately, Dante does not specify whether these four heads are human or beastly. Since the ox heads already have two horns and these four have only one horn on top of their heads, I suggest that they are grotesque human heads. Again, this image comes from the Book of Revelation (13:1): “I saw a beast come out of the sea with ten horns and seven heads.” Throughout the centuries, these seven heads and ten horns have caused scholars grief in their attempts to interpret them. Some interpreters think of the seven horns as the Seven Sacraments and the ten horns as the Ten Commandments. One early interpretation that seems to work better than most is that they represent the Seven Deadly Sins. And some commentators give one or two horns to each sin depending on whether they offend only God or God and neighbor. Thus, Pride, Envy, and Wrath (Anger ), the worst of the sins, have two horns. While Avarice, Sloth, Gluttony, and Lust are lesser sins and have only one horn. That these heads and horns grow on the chariot itself indicates that much of the Church’s corruption has come from within. Regardless of different later interpretations, Dante offers his own-–a monstrosity, a parody, a horror, a vision of the Church’s corruption as it has strayed from the simplicity of the Gospel.

18. In this seventh scene, the grotesque chariot-–once glorious and occupied by Beatrice-–is now occupied by a naked whore, kissed and slapped about by her pimp-giant. Ultimately, the jealous giant (Philip IV of France) unhitches the chariot and drags it off in to the forest until it can no longer be seen. But this shameless whore is not a weakling. She sits as firmly on the chariot as a castle on a hilltop. Representing the corrupt papacy that ends up removed from Rome to Avignon (the forest) in 1309, this image of the Whore of Babylon fornicating with the kings of the earth comes again from the Book of Revelation (Chapter 17). The whore’s lusty glances at Dante are difficult to interpret. It is interesting to consider whether the “me” is the Poet or the Pilgrim. Perhaps the “glances,” at least, may represent Boniface VIII’s behind-the-scenes involvement with Dante’s exile. Her being beaten by the giant most likely relates to the incident where Philip IV’s thugs briefly imprisoned and beat Boniface VIII at his castle in 1303.

Top of page