Dante's Divine Comedy

Introduction

Dante Alighieri (1265-1321) was born into a noble Florentine family in a city torn apart by rival clans. While feudal aristocracy backed imperial authority (Ghibellines), the Alighieri family supported the pope (Guelphs). Their party eventually splintered into hostile White and Black factions. Offended by Pope Boniface VIII's interference in secular affairs, Dante, too, became embroiled in this sectarianism and joined the White Guelphs. He was banished following the Black Guelph victory of 1302. Although he enjoyed the patronage of powerful northern Italian princes, his future political allegiances were misguided. He died in exile in Ravenna in 1321.

The Divine Comedy, the first book to be written in the Italian vulgare instead of Latin, was begun in 1308 and contains three cantiche—Inferno (Hell), Purgatorio (Purgatory) and Paradiso (Paradise)—written in terza rima, a verse scheme of three-line stanzas with interlocking rhyme patterns (aba, bcb, cdc, and so on). Dante's influences included the classics, the neo-Platonists, Aristotle, natural philosophy and theology. The Inferno's opening canto is a microcosm of the entire work and its topography prefigures the three realms of the soul's afterlife: the dark wood (Hell), the barren slope (Mount Purgatory) and the blissful mountain (Paradise).

The epic poem juxtaposes human privation, injustice and imperfection with divine freedom, justice and perfection. Dante's allegorical theme of God's gradual revelation to an unsuspecting, unprepared pilgrim beautifully illustrates the concept of the rational human soul choosing salvation of its own free will. The use of real-life characters, autobiographical detail, personal failures and triumphs, sophisticated eschatological discourse and the denunciation of contemporary politics renders the poem unique. The images remain unsurpassed—galloping centaurs, devils, chained giants, cannibalism, dazzling angels, supernatural rivers and trees, configurations of lights and a heavenly stadium.

The symbolism of each realm with its various landscapes, rivers, guardians, inhabitants, pageants and dramas, combined with important number patterns (seven terraces, nymphs and capital sins; the Trinity; Lucifer's three faces; Cerberus' three heads, the heavenly trio (Mary, Lucy and Matilda); three theological virtues; the triune nature of Geryon; and three beasts and three Furies), gives the poem a tight complexity.

The technique of having two Dante characters, the Poet and the Pilgrim, allows the narrative to reach out to the universal reader whilst operating on a personal level. During his spiritual journey, the pilgrim participates in the sin of every sinner, the penance of every repentant soul and the bliss of the blessed—he is Everyman. Sometimes his pity is stirred by the damned—many sinners try to trick him (Inf. V) and each other (Inf. XXI-XXIII)—which threatens his safety. Exchanges in Hell are hurried, devious and insincere, in marked contrast with the stoical patience of Purgatory and Heaven's peaceful eternity.

Beatrice's intervention when the pilgrim is lost and contemplating suicide (Inf. I) reveals that benign forces have authorized the whole pilgrimage. God's supervision is also evident from the events paralleling the Advents of Christ: the arrival of the angel at the gates of Dis (Inf. IX) is like the First Coming or Christ's Harrowing of Hell; the pair of angels making their descent into the valley (Purg, VIII) is like the Second Coming or Christ entering Christian hearts; and Beatrice appears in the Earthly Paradise (Purg. XXX) like the Third Coming or Final Judgment.

Virgil and Beatrice embody qualities that change with major shifts in the narrative. Where logic is required over faith (Hell), Virgil is a wonderful personification of reason or human wisdom: he wards off danger and shows the way in spite of his pre-Christian limitations (Inf. IX). Where faith supersedes reason, he fades into the background (Purg. III) and feels self-conscious (Purg. VII, XXI), his answers limited by a lack of Christian knowledge (Purg. VI). Stepping in to pass judgment on the pilgrim after he has been crowned and mitred by Virgil is Beatrice (Purg. XXVII). She appears on the pageant's chariot as the Sacrament of the Body of Christ in the Church. No longer just an earthly model of beauty and courtesy, she now embodies divine wisdom, revelation and grace (Purg. XXX) and in her eyes is reflected the dual nature of Christ in the Griffin (Purg. XXXI).

Inferno (Hell)

Dante categorizes sin as being without malice (Incontinence) or with malicious intent (Violence or Fraud). Cowardice and indecisiveness escape this dichotomy and are marginalized within Limbo. Heresy is in a kind of no-man's land as it refutes Christian reality and the soul's immortality yet does not involve sinful action. Hell, under the city of Jerusalem in the Northern Hemisphere, extends funnel-like into the earth's core. Dante and Virgil are forced to climb down Lucifer's body because Mount Purgatory lies in the opposite (Southern) Hemisphere.

The pilgrim's behavior sometimes mirrors that of the damned—for example, he chooses not to interact with the Indecisives (Inf. III); he compares his excusable vandalism of church property with Boniface's inexcusable destruction of the Church's foundations (Inf. XIX); and the language he uses when conversing with the Thieves suggests that he is contributing to the transformations themselves (Inf. XXIV).

Here are a few examples of contrapasso (the logical relationship between punishment and offense). The Suicides severed ties with their body so they will be denied human form on Judgment Day (Inf. XIII). The Profligates, who were violently wasteful, are chased and torn by dogs through trees because property was seen as an extension of the body and this kind of violence was tantamount to suicide (Inf. XIII). The Flatterers are immersed in their verbal diarrhea (Inf. XVIII). The Simonists are given inverted baptisms with fire to illustrate their ecclesiastical perversion (Inf. XIX). The Benedictine garb of the Hypocrites condemns their false piety (Inf. XXIII) whilst the Thieves' multiple transformations parody reincarnation and reflect their inability to separate 'mine' from 'thine' (Inf. XXV). Fraudulent, silver-tongued rhetoric is condemned by the flaming tongues that consume the evil counselors (Inf. XXVI-XXVII) while those who divided institutions, communities and families are ripped open (Inf. XXVIII). The corrosive influence of falsification on metals (Alchemists), money (Counterfeiters), identity (Imposers) and truth (Liars) is fittingly expressed through the diseased state of their bodies and minds (Inf. XIX-XXX).

Church doctrine unfolds within a dark, noisy, smelly and antagonistic panorama where teachings are witnessed through the actions of sinners. As the pilgrim progresses through Purgatory on his way to Paradise, learning more and more by example, he hears long discourses about philosophical and theological doctrine from his teachers (Virgil, Beatrice, Statius, Lucy, Saint Bernard) until his faith comes to be examined by three of the Apostles (Peter, James and John).

Purgatorio (Purgatory)

Hell and Heaven are eternal states. Purgatory is a place of transition where souls do penance and are in contact with the living (Purg. XXXIII). Death's second kingdom is courteous yet disciplined with a gatekeeper at Peter's Gate, the Rule of the Mountain and angel guardians stationed all the way up the terraces to the Earthly Paradise. It is fitting that the journey from Ante-Purgatory to the First Cornice should be the most arduous.

The mood is one of joy—lovers are reunited and all souls are bound for Heaven—but there is melancholy and austerity here as well because acute contrition is required to purge the stain of capital sin. Rituals to eradicate its root include penitence (Purg. IX, XXXI), a seven-fold pardon and two baptisms—one by water(Purg. XXXIII), the other by fire (Purg. XXVII). In a reversal of Inf. XVI, when Virgil cast off his pupil's cord (foolish self-confidence) before entering Lower Hell, the pilgrim girds himself with a reed (Purg. I) to clothe his spirit in humility.

Everywhere there is the promise of God's love: in visions of the Host (the Sun, Beatrice riding the chariot), Cato's face (Purg. I), the ship of souls (Purg. II), the murmur of prayer and angelic voices, the pageants(Purg. XXIX, XXX, XXXII) and the seven terrace warders. Punishment is borne willingly. On every cornice, penitence comprises the penance itself followed by a meditation made up of the Whip (examples of the opposing virtue) and the Bridle (deterrent examples of the sin), plus a prayer, a benediction and the pardon of the angel.

Paradiso (Paradise)

The structure of the heavenly ascent is based on the accepted Ptolemaic model—seven concentric planetary spheres revolving around the Earth. Beyond Saturn, the planets are enclosed in the Starry Heaven, where changeless angelic intelligences control the motion and order of the visible universe circling around the Primum Mobile, which is motionless. The abode of God, the Empyrean or Tenth Heaven, lies beyond time, space and movement.

Dante places different groups of souls on each level to represent the stages of spiritual advancement that are possible through the active and the contemplative life. This arrangement does not physically exist of course—all souls share one God and one Heaven and are not attached to a particular sphere (Par. IV)—but it is part of God's plan to provide some sort of sequence so that the pilgrim may be able to grasp a fragment of the ultimate reality of it all.

The tone of Paradise is at once liturgical, lyrical and scientific, dominated by the presence of light, song, discourse, visions and revelations. A sense of harmony, of spirits united in love and will, is reflected in the encounters and conversations with the souls (manifested as light forms) who speak, sing or blush in anger at humanity's earthly wrongdoings. The blessedness of unity with God is conveyed in those cantos where souls are not presented individually but as part of a symbolic figure or a larger whole: the double configuration of lights (Par. XII-XIII), the ruby-studded Cross (Par. XIV-XV), the eagle of justice (Par. XIX-XX), the ladder (Par. XXI), the lit-up message (Par. XVIII) and, finally, the mystic rose (Par. XXX-XXXII).

Paradise is a blinding vision beyond human comprehension where words fall short yet astounding lucidity prevails: the indescribable beauty of Beatrice's face when the Empyrean momentarily shines through her (Par. III); the radiance of the blessed wearing their body of glory (Par. XXXII); Dante gazing into the divine light and seeing the created universe in its entirety (Par. XXXIII); the mystery of the Holy Trinity expressed through geometric perfection (Par. XXXIII).

Anna Amari-Parker, 2006

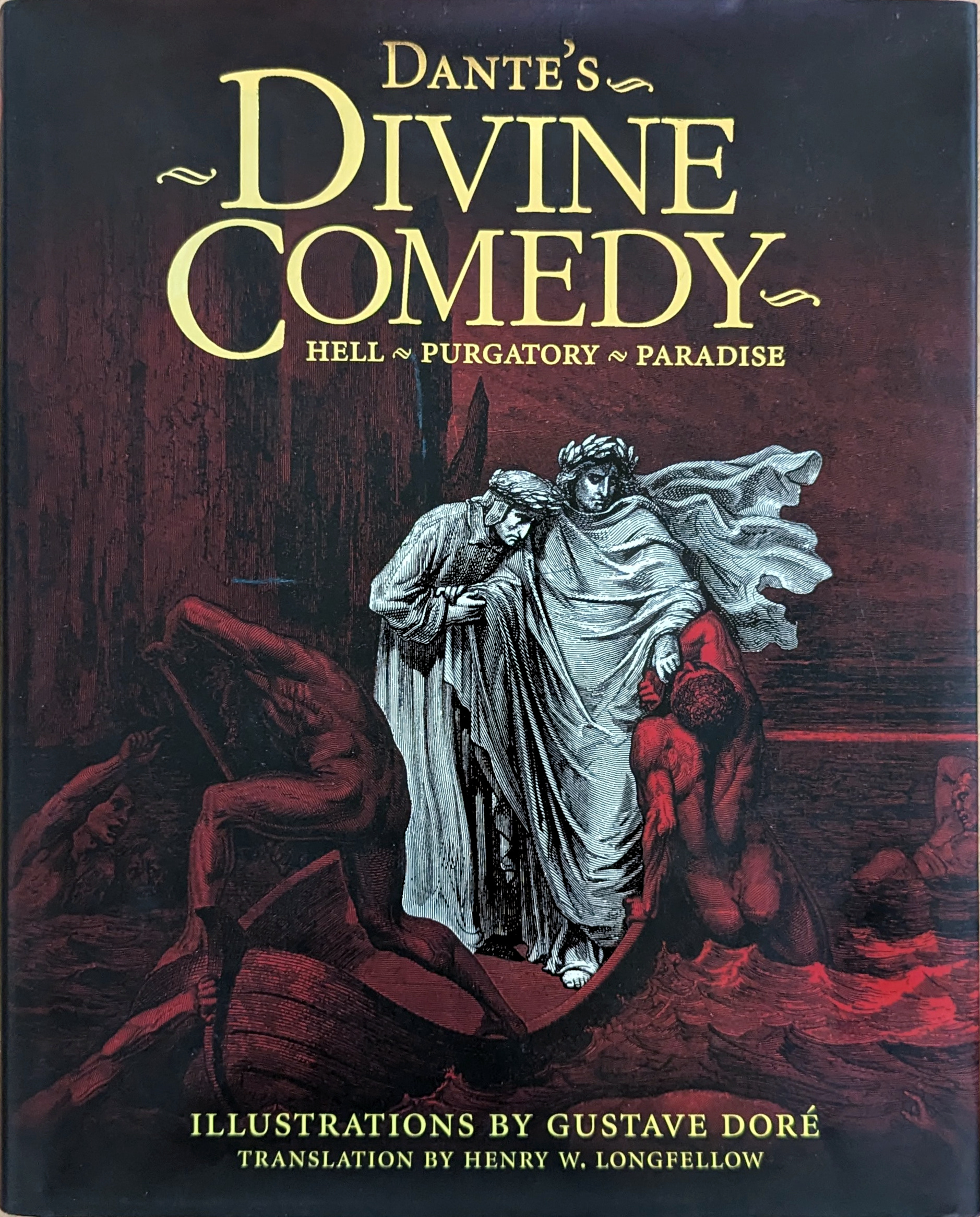

Cover

Dante's Divine Comedy, by Henry W Longfellow; Illustrations by Gustave Dore

Note: According to gutenburg.org, Longfellow's version is no longer under copyright.

Top of page