Dante's Divine Comedy: Purgatorio

Canto IV

Virgil and Dante walk with the excommunicated souls along the terrace until they reach a steep rock face on the side of the mountain. The poets enter the Second Terrace of Ante-Purgatory which is occupied by the Late Repentant (the first sub-group of which are the Indolent). The Florentine instrument-maker Belacqua explains to them that, although such souls remained within the bosom of the Church, they chose a tardy repentance and must now endure a delay equal in length to the duration of their earthly lives before being pardoned. Dante wonders why the sun is always on their left and Virgil explains the paradox to him.

Whenever by delight or else by pain,

That seizes any faculty of ours,

Wholly to that the soul collects itself,

It seemeth that no other power it heeds;

And this against that error is which thinks

One soul above another kindles in us.

And hence, whenever aught is heard or seen

Which keeps the soul intently bent upon it,

Time passes on, and we perceive it not,

Because one faculty is that which listens,

And other that which the soul keeps entire;

This is as if in bonds, and that is free.

Of this I had experience positive

In hearing and in gazing at that spirit;

For fifty full degrees uprisen was

The sun, and I had not perceived it, when

We came to where those souls with one accord

Cried out unto us: "Here is what you ask."

A greater opening ofttimes hedges up

With but a little forkful of his thorns

The villager, what time the grape imbrowns,

Than was the passage-way through which ascended

Only my Leader and myself behind him,

After that company departed from us.

One climbs Sanri and descends in Noli,

And mounts the summit of Bismantova,

With feet alone; but here one needs must fly;[1]

With the swift pinions and the plumes I say

Of great desire, conducted after him

Who gave me hope, and made a light for me.

We mounted upward through the rifted rock,

And on each side the border pressed upon us,

And feet and hands the ground beneath required.

When we were come upon the upper rim

Of the high bank, out on the open slope,

"My Master," said I, "what way shall we take?"

And he to me: "No step of thine descend;

Still up the mount behind me win thy way,

Till some sage escort shall appear to us."

The summit was so high it vanquished sight,

And the hillside precipitous far more

Than line from middle quadrant to the center.

Spent with fatigue was I, when I began:

"O my sweet Father! turn thee and behold

How I remain alone, unless thou stay!"

"O son," he said, "up yonder drag thyself,"

Pointing me to a terrace somewhat higher,

Which on that side encircles all the hill.

These words of his so spurred me on, that I

Strained every nerve, behind him scrambling up,

Until the circle was beneath my feet.

Thereon ourselves we seated both of us

Turned to the East, from which we had ascended,

For all men are delighted to look back.

To the low shores mine eyes I first directed,

Then to the sun uplifted them, and wondered

That on the left hand we were smitten by it.

The Poet well perceived that I was wholly

Bewildered at the chariot of the light,

Where 'twixt us and the Aquilon it entered.[2]

Whereon he said to me: "If Castor and Pollux

Were in the company of yonder mirror,

That up and down conducteth with its light,

Thou wouldst behold the zodiac's jagged wheel

Revolving still more near unto the Bears,

Unless it swerved aside from its old track.

How that may be wouldst thou have power to think,

Collected in thyself, imagine Zion

Together with this mount on earth to stand,

So that they both one sole horizon have,

And hemispheres diverse; whereby the road

Which Phaeton, alas! knew not to drive,[3]

Thou'lt see how of necessity must pass

This on one side, when that upon the other,

If thine intelligence right clearly heed."

"Truly, my Master," said I, "never yet

Saw I so clearly as I now discern,

There where my wit appeared incompetent,

That the mid-circle of supernal motion,

Which in some art is the Equator called,

And aye remains between the Sun and Winter,

For reason which thou sayest, departeth hence

Tow'rds the Septentrion, what time the Hebrews

Beheld it tow'rds the region of the heat.[4]

But, if it pleaseth thee, I fain would learn

How far we have to go; for the hill rises

Higher than eyes of mine have power to rise."

And he to me: "This mount is such, that ever

At the beginning down below 'tis tiresome,

And aye the more one climbs, the less it hurts.

Therefore, when it shall seem so pleasant to thee,

That going up shall be to thee as easy

As going down the current in a boat,

Then at this pathway's ending thou wilt be;

There to repose thy panting breath expect;

No more I answer; and this I know for true."

And as he finished uttering these words,

A voice close by us sounded: "Peradventure

Thou wilt have need of sitting down ere that."

At sound thereof each one of us turned round,

And saw upon the left hand a great rock,

Which neither I nor he before had noticed.

Thither we drew; and there were persons there

Who in the shadow stood behind the rock,

As one through indolence is wont to stand.

And one of them, who seemed to me fatigued,

Was sitting down, and both his knees embraced,

Holding his face low down between them bowed.

"O my sweet Lord," I said, "do turn thine eye

On him who shows himself more negligent

Then even Sloth herself his sister were."

Then he turned round to us, and he gave heed,

Just lifting up his eyes above his thigh,

And said: "Now go thou up, for thou art valiant."

Then knew I who he was; and the distress,

That still a little did my breathing quicken,

My going to him hindered not; and after

I came to him he hardly raised his head,

Saying: "Hast thou seen clearly how the sun

O'er thy left shoulder drives his chariot?"

His sluggish attitude and his curt words

A little unto laughter moved my lips;

Then I began: "Belacqua, I grieve not[5]

For thee henceforth; but tell me, wherefore seated

In this place art thou? Waitest thou an escort?

Or has thy usual habit seized upon thee?"

And he: "O brother, what's the use of climbing?

Since to my torment would not let me go

The Angel of God, who sitteth at the gate.

First heaven must needs so long revolve me round

Outside thereof, as in my life it did,

Since the good sighs I to the end postponed,

Unless, e'er that, some prayer may bring me aid

Which rises from a heart that lives in grace;

What profit others that in heaven are heard not?"

Meanwhile the Poet was before me mounting,

And saying: "Come now; see the sun has touched

Meridian, and from the shore the night[6]

Covers already with her foot Morocco."

Illustrations of Purgatorio

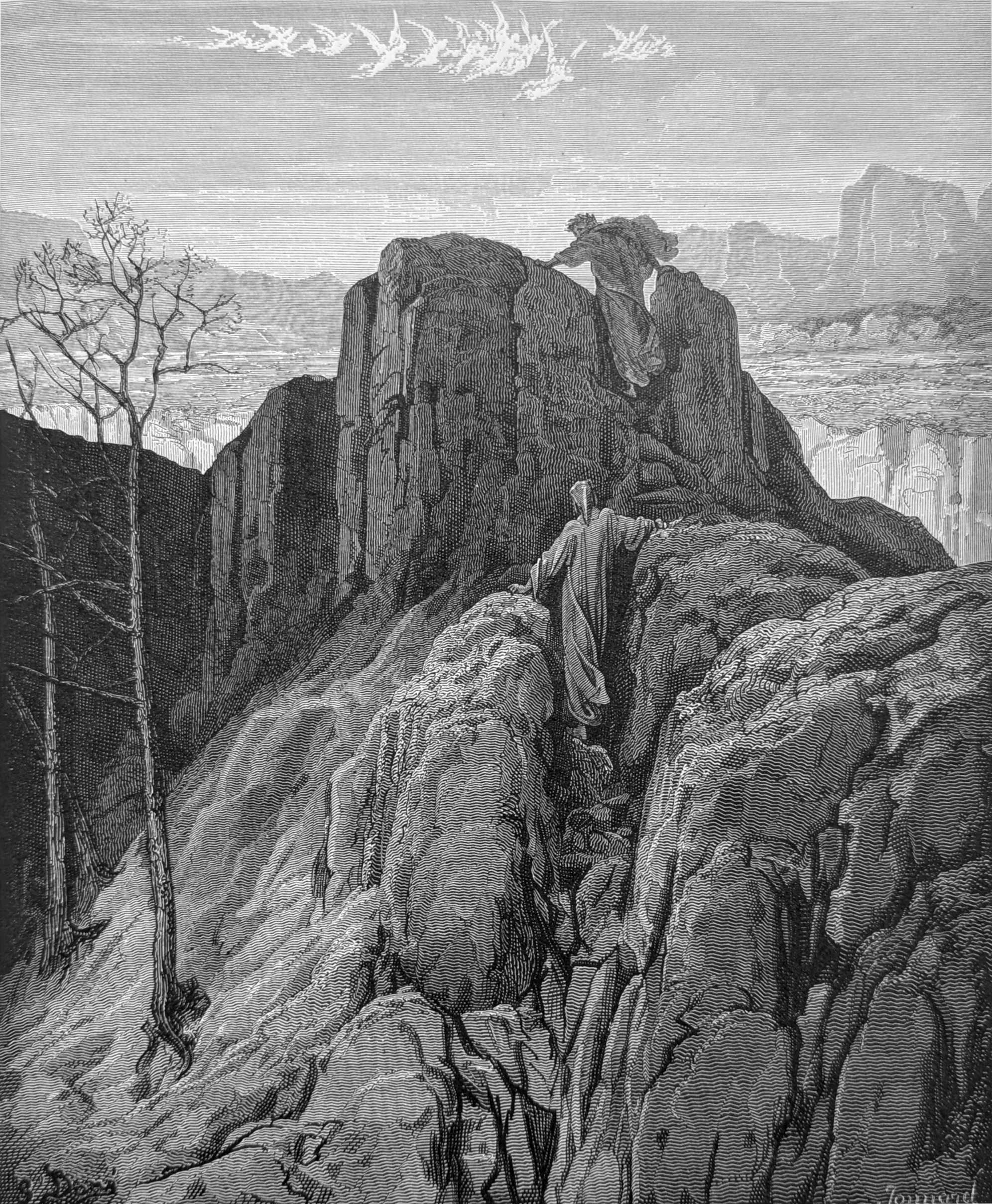

We mounted upward through the rifted rock, And on each side the border pressed upon us, Purg. IV, lines 31-32

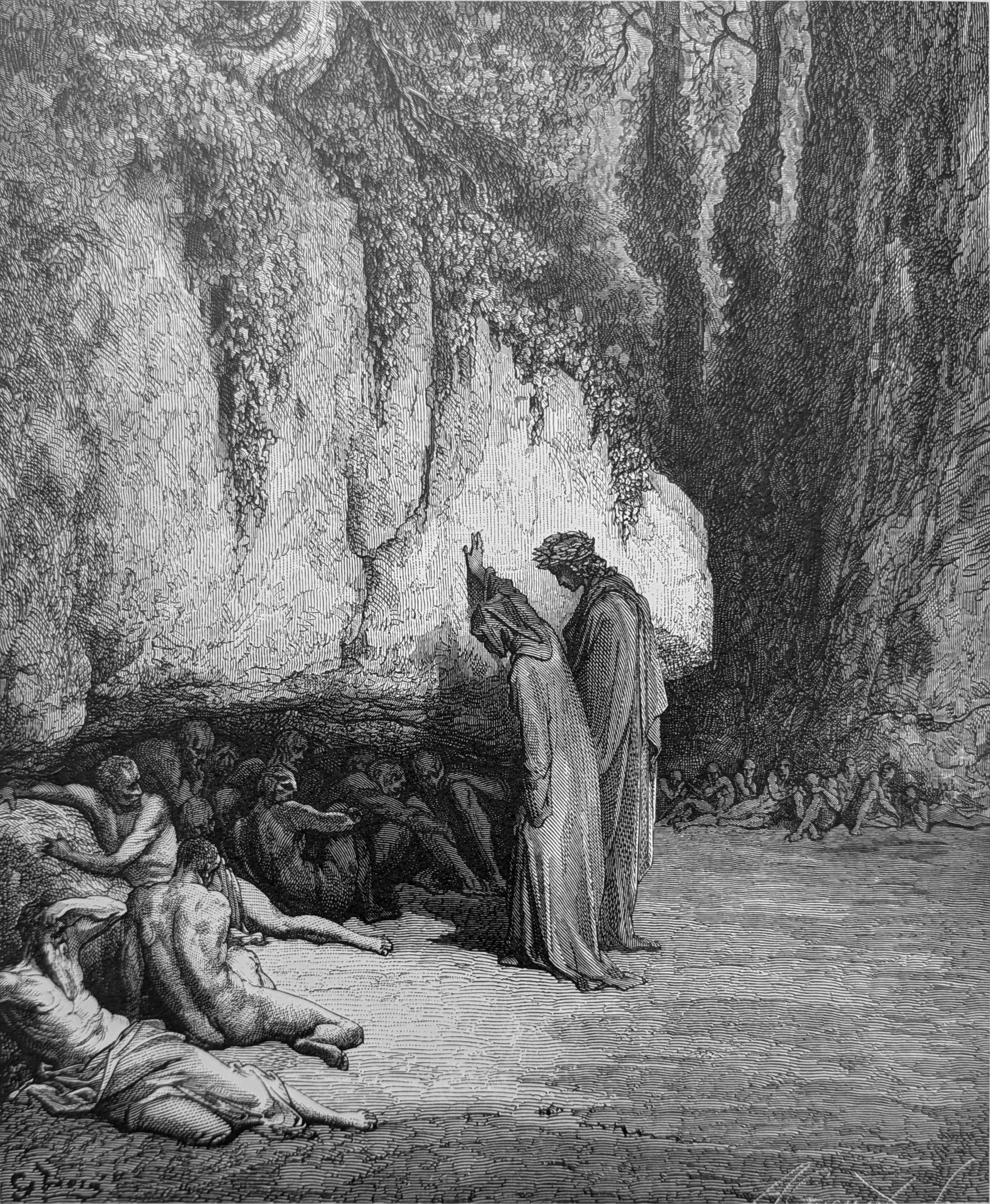

Thither we drew; and there were persons there / Who in the shadow stood behind the rock, / As one through indolence is wont to stand. Purg. IV, lines 103-105

Footnotes

1. He refers to San Leo, just to the west and south of the Republic of San Marino. Climbing up to this mountain town was exceedingly difficult. Noli is about 30 miles to the west of Genoa on the Ligurian coast. In Dante’s time, one could only get there by the sea or by a precipitous climb down from the mountainous region above it. Mount Bismantova is most likely a reference to what is called the Rock of Bismantova, southwest of the city of Reggio Emilia about 25 miles. It is an immense, tall, flat-topped up-crop ping (mesa) whose cliff sides would have been perfect images for the initial climb upward in Purgatory. And with this bit of geography out of the way, Dante becomes a bird again, this time with wings fueled by his great desire to move upward. Virgil leads t he way.

2. Sitting on a ledge of the Mountain of Purgatory, Dante wants us to understand that Purgatory is a physical place antipodal or directly opposite the city of Jerusalem on the globe. This would put it somewhere in the Pacific Ocean between Santiago, Chile and Sydney, Australia, but still some 4-5 thousand miles north of the South Pole. Understand, of course, that the southern hemisphere was understood to be almost completely covered with water.

Dante and Virgil are facing east, the direction they started from, and from which they watched the glorious sunrise upon their emergence from the darkness of Hell. Dante is scanning the landscape to give us a sense of their position. Looking down, it’s clear that they have climbed quite a distance, the shore seems far away, but the sun–now to their left (north)–is not where Dante thought it would be. Recall that he had been talking with Manfred for three hours before he began to climb, which itself has taken some time. Being from the northern hemisphere, he’s obviously used to seeing the sun rise in the east to his right. Virgil (actually the Poet) will “clear up” his companion’s confusion with some rather “opaque” observations. Since Jerusalem and Purgatory ar e on opposite sides of the globe, they share a common horizon no matter which way they look. But in the northern hemisphere, the sun will always be south of the observer, and in the southern horizon, the sun will always be north of the observer. Right now, it is the beginning of spring, Virgil reminds Dante, and the sun is in Aries. But as the months move toward summer, Aries will give way to Gemini and the sun will be farther north, etc. Dante’s mention of the Ecliptic, the Zodiac, and the Equator here are a bit “over the top,” and in a way confuse the issue. Virgil, it would seem, said the same thing. Dante, signifying that he understands Virgil, not-so-simply does so by using the astronomical terms for what his mentor explained quite clearly with the shared horizon.

3. Phaethon is the son of Helios who did not head his father's warning and drove the charion to disaster.

4. Latin, septentriones, the seven stars of the Plough (Big Dipper), meaning to the north.

5. Belacqua, like Dante, was a Florentine and apparently a maker of musical instruments. Otherwise, we don’t know much about him. Yet, he seems to fit into Dante’s framework for this part of Purgatory perfectly because it was said of him by the Anonimo Fiorent in (quoted by Ciardi) that “he was the most indolent man who ever lived.” Apparently, Dante would frequently criticize him for his laziness, and the anonymous commentator tells us that Belacqua once quoted Aristotle (Phys. 7.3.247b) back to Dante, saying:” Sitting in quietness makes the soul wise.” Dante is said to have replied: “Certainly if sitting makes one wise, no one has ever been wiser than you!” Nevertheless, he’s an endearing character and adds a definite lightness to this canto that has been quite rather sober up to this point.

6. Virgil, taking the lead again, brings Dante back from his distraction with Belacqua by reminding him of the time. If it’s now noon time on the Mountain of Purgatory, the Pilgrims have been here for about six hours, having emerged from Hell at sunrise. They left Manfred and began climbing about two and a half hours ago or 10:30am. The mention of dusk in Morocco (the western limit of the inhabited world) seems rather gratuitous except that it’s another way of telling Dante that it’s noon. Recalling that Purgatory is antipodal to Jerusalem, it’s midnight there and 90̊ to the west it’s 6:00pm in Morocco. All of this, of course, is designed to heighten the sense of urgency and the need to hasten toward the travelers’ goal.

Some final thoughts on Morocco lead Martinez and Durling, in their Purgatorio commentary, to note the several subtle references to Ulysses (Inferno 26) in this canto. They note Dante’s amazement at the height of the Mountain of Purgatory and Ulysses’ same observation. They contrast the “mad flight” toward the west by Ulysses and his crew with Dante and Virgil sitting on the ledge looking east. And the metaphor of flight is used again by Ulysses, who calls the oars in his boat “wings,” and Dante who tells us h e and Virgil needed wings and become like birds to climb such a steep mountain face. Finally, the mention of Morocco. Ulysses passes Morocco, the western limit of the known world, the end of human habitation, and “the last shore touched by the sunlight [God ] as the night moves westward.” Virgil’s mention of Morocco is not at all tragic, but simply a way of telling time–time to continue climbing the Mountain with the strength of humility in contrast to Ulysses, who thought to conquer it with his hubris and pride.

Top of page