Dante's Divine Comedy: Purgatorio

Canto V

In the Second Terrace of Ante-Purgatory, Dante and Virgil meet a group of the Late Repentants, who are singing the Miserere. Although they had died under violent circumstances or had otherwise met an untimely death, they had still managed to repent. Dante converses with Jacopo del Cassero, a Guelf supporter from Fano; Buonconte da Montefeltro, son of Guido from Hell's Canto XXVII; and Lady Pia dei Tolomei, a Sienese aristocrat murdered by her husband, to whom she was forcibly betrothed. They ask Dante to assist them when he is back in the world again.

I had already from those shades departed,

And followed in the footsteps of my Guide,

When from behind, pointing his finger at me,

One shouted: "See, it seems as if shone not

The sunshine on the left of him below,

And like one living seems he to conduct him."

Mine eyes I turned at utterance of these words,

And saw them watching with astonishment

But me, but me, and the light which was broken!

"Why doth thy mind so occupy itself,"

The Master said, "that thou thy pace dost slacken?

What matters it to thee what here is whispered?

Come after me, and let the people talk;

Stand like a steadfast tower, that never wags

Its top for all the blowing of the winds;

For evermore the man in whom is springing

Thought upon thought, removes from him the mark,

Because the force of one the other weakens."

What could I say in answer but "I come"?

I said it somewhat with that color tinged

Which makes a man of pardon sometimes worthy.

Meanwhile along the mountain-side across

Came people in advance of us a little,

Singing the Miserere verse by verse.[1]

When they became aware I gave no place

For passage of the sunshine through my body,

They changed their song into a long, hoarse "Oh!"

And two of them, in form of messengers,

Ran forth to meet us, and demanded of us,

"Of your condition make us cognizant."

And said my Master: "Ye can go your way

And carry back again to those who sent you,

That this one's body is of very flesh.

If they stood still because they saw his shadow,

As I suppose, enough is answered them;

Him let them honor, it may profit them."

Vapors enkindled saw I ne'er so swiftly

At early nightfall cleave the air serene,

Nor, at the set of sun, the clouds of August,

But upward they returned in briefer time,

And, on arriving, with the others wheeled

Tow'rds us, like troops that run without a rein.

"This folk that presses unto us is great,

And cometh to implore thee," said the Poet;

"So still go onward, and in going listen."

"O soul that goest to beatitude

With the same members wherewith thou wast born,"

Shouting they came, "a little stay thy steps,

Look, if thou e'er hast any of us seen,

So that o'er yonder thou bear news of him;

Ah, why dost thou go on? Ah, why not stay?

Long since we all were slain by violence,

And sinners even to the latest hour;

Then did a light from heaven admonish us,

So that, both penitent and pardoning, forth

From life we issued reconciled to God,

Who with desire to see Him stirs our hearts."

And I "Although I gaze into your faces,

No one I recognize, but if may please you

Aught I have power to do, ye well-born spirits,

Speak ye, and I will do it, by that peace

Which, following the feet of such a Guide,

From world to world makes itself sought by me."

And one began: "Each one has confidence

In thy good offices without an oath,

Unless the I cannot cut off the I will;

Whence I, who speak alone before the others,

Pray thee, if ever thou dost see the land

That 'twixt Romagna lies and that of Charles,[2]

Thou be so courteous to me of thy prayers

In Fano, that they pray for me devoutly,

That I may purge away my grave offenses.

From thence was I; but the deep wounds, through which

Issued the blood wherein I had my seat,

Were dealt me in bosom of the Antenori,[3]

There where I thought to be the most secure;

Twas he of Este had it done, who held me

In hatred far beyond what justice willed.

But if towards the Mira I had fled,

When I was overtaken at Oriaco,

I still should be o'er yonder where men breathe.

I ran to the lagoon, and reeds and mire

Did so entangle me I fell, and saw there

A lake made from my veins upon the ground."

Then said another: "Ah, be that desire

Fulfilled that draws thee to the lofty mountain,

As thou with pious pity aidest mine.

I was of Montefeltro, and am Buonconte;

Giovanna, nor none other cares for me;

Hence among these I go with downcast front."[4]

And I to him: "What violence or what chance

Led thee astray so far from Campaldino,

That never has thy sepulture been known?"

"Oh," he replied, "at Casentino's foot

A river crosses named Archiano, born

Above the Hermitage in Apennine.

There where the name thereof becometh void

Did I arrive, pierced through and through the throat,

Fleeing on foot, and bloodying the plain;

There my sight lost I, and my utterance

Ceased in the name of Mary, and thereat

I fell, and tenantless my flesh remained.

Truth will I speak, repeat it to the living;

God's Angel took me up, and he of hell

Shouted: 'O thou from heaven, why dost thou rob me?

Thou bearest away the eternal part of him,

For one poor little tear, that takes him from me;

But with the rest I'll deal in other fashion!'

Well knowest thou how in the air is gathered

That humid vapor which to water turns,

Soon as it rises where the cold doth grasp it.

He joined that evil will, which aye seeks evil,

To intellect, and moved the mist and wind

By means of power, which his own nature gave;

Thereafter, when the day was spent, the valley

From Pratomagno to the great yoke covered

With fog, and made the heaven above intent,[5]

So that the pregnant air to water changed;

Down fell the rain, and to the gullies came

Whate'er of it earth tolerated not;

And as it mingled with the mighty torrents,

Towards the royal river with such speed

It headlong rushed, that nothing held it back.

My frozen body near unto its outlet

The robust Archian found, and into Arno

Thrust it, and loosened from my breast the cross

I made of me, when agony o'ercame me;

It rolled me on the banks and on the bottom,

Then with its booty covered and begirt me."

"Ah, when thou hast returned unto the world,

And rested thee from thy long journeying,"

After the second followed the third spirit,

"Do thou remember me who am the Pia;

Siena made me, unmade me Maremma;

He knoweth it, who had encircled first,[6]

Espousing me, my finger with his gem."

Illustrations of Purgatorio

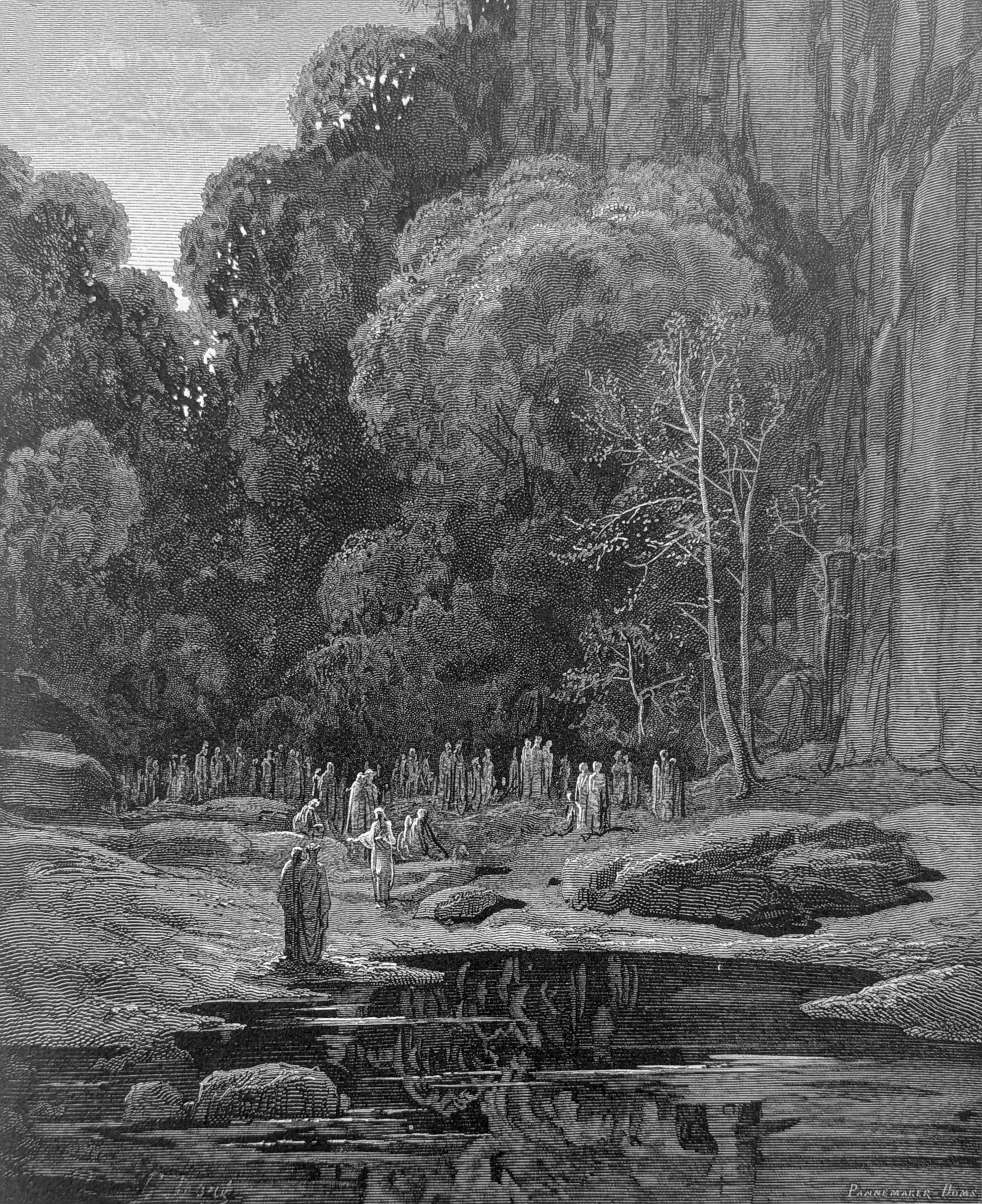

Meanwhile along the mountain-side across / Came people in advance of us a little, / Singing the Miserere verse by verse. Purg. V, lines 22-24

"God's Angel took me up, and he of hell / Shouted: ‘O thou from heaven, why dost thou rob me?" Purg. V, lines 104-105

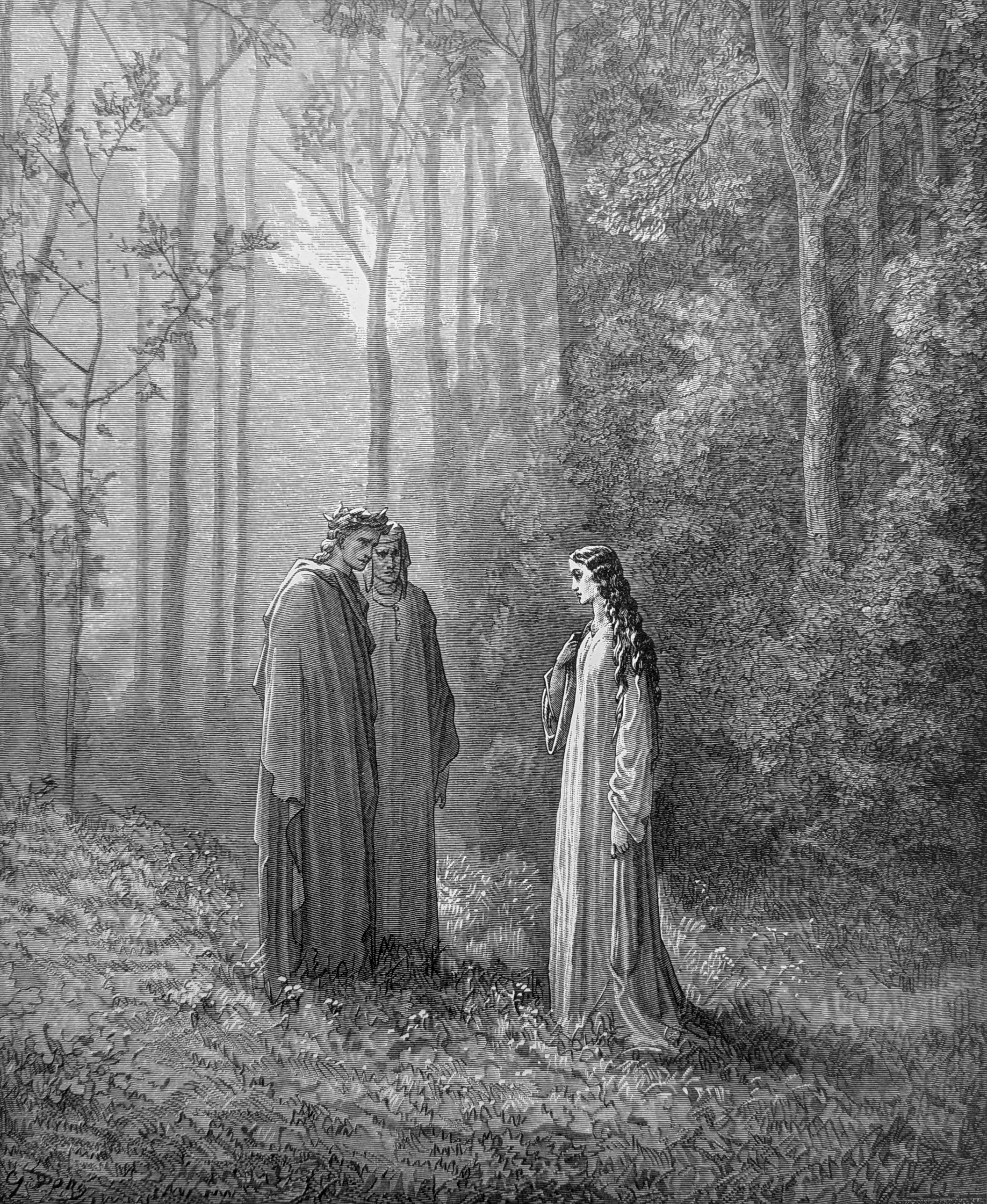

"Do thou remember me who am the Pia; / Siena made me, unmade me Maremma;" Purg. V, lines 133-134

Footnotes

1. Miserere, Miserere mei, Deus, Latin, "Have mercy on me, O God", is a setting of Psalm 51. The Miserere is the ancient name given to Psalm 51, coming from its first words, “Have mercy on me…” It’s the most important of what are known as The Seven Penitential Psalms (6, 32, 38, 51, 102, 130, and 143), highlighting the themes of the mercy and forgiveness of God–-a fitting hymn to summarize what happens here in Purgatory.

2. This first speaker does not identify himself, but from his story and the places he names we know that he was Jacopo del Cassero (1260-1298) whom Dante may have known because they both participated in the Florentine Guelf campaign against Arezzo in 1288. Alt hough Dante said he didn’t recognize any of the souls in this group, differences in time and circumstances between them may account for this. Jacopo was a well-known nobleman from the town of Fano on the Adriatic between Rimini in the north and Ancona in the south. He was the Podestà (the chief civil magistrate in Medieval Italian cities) of Rimini in 1294, of Bologna in 1296, and he was on his way to Milan to assume the same position in 1298 when he was assassinated by henchmen of Azzo VIII of Este (a town 2 0 miles southwest of Padua), a brutal megalomaniac whose schemes of expansion included Bologna where Jacopo was Podestà. Jacopo, of course, stood in the way. At the time of Jacopo’s death, Azzo was the lord of Ferrara, Modena and Reggio (cities that between them form a large swath of territory northeast and northwest of Bologna). Jacopo had apparently sailed to Venice and traveled toward Padua on his way to becoming Podestà of Milan when he was killed near Oriago, just west of Venice. Traveling this way most likely enabled him to avoid any of the territories of Azzo. Unfortunately, death caught up with him there in that swampy region. Note the element of chance: he tells Dante that if he had traveled to Mira, a town just a mile or two southwest of Oriago, on the way to Padua, he would still be alive. The people there would have protected him.

3. And there is another, darker and more subtle, connection at work here as Dante fashions this story of treachery. Padua, according to legend, was founded by Antenor who betrayed the city of Troy to the Greeks. Recall that, at the bottom of Hell, the frozen lake of Cocytus is divided into four parts–one of them called Antenora, reserved for those who betrayed their country. It should be said, however, that the Antenori (Paduans), as I noted above, would most likely have protected Jacopo from the likes of Azzo and his assassins.

4. The speaker here identifies himself as Buonconte da Montefeltro, and like Jacopo before him, his request is couched in gracious language. And yet, there is a great sadness to his story because no one in his hometown, including his wife, Giovanna, seems to remember or care about him which causes him great embarrassment. Like others before him, though he doesn’t say so directly, he, too, wants prayers that will speed him on his way to penitence in Purgatory proper.

Before commenting further, it’s important to note that Buonconte–here in Purgatory–is the son of Guido da Montefeltro whom we met in Inferno 27. Both father and son have rather twisted stories, and both have similar endings, but with different results. Guido appeared to Dante and Virgil in the Inferno as a rather whimpering soul wrapped in a tongue of flame after Ulysses narrated the amazing story of his final voyage. He had been a famed military strategist, but later in life, he gave up his former ways and became a Franciscan monk. This might have saved him if it hadn’t been for Pope Boniface VIII (Dante’s nemesis), who wanted to destroy the city of Palestrina in the foothills just to the east of Rome. Coming to the now-monk Guido, Boniface wanted a successful strategy that would give him victory. Despite Guido’s refusal, the evil pope got his way by promising him absolution before he committed the sin. This was his downfall.

Returning to Buonconte, Dante pities his situation and asks a curious question that leads to a fascinating answer. Dante wants to know why his body was never found after the famous Battle of Campaldino where the Guelfs slaughtered the opposing Ghibelline forces. Dante, in fact, was a Florentine cavalryman in that battle. Though Buonconte was the Captain of the defeated Aretine army, and he and Dante would have been enemies, here in Purgatory, there is no rancor between them, only curiosity and a gracious willingness to help. The quick answer to Dante’s question is that Buonconte’s body lies somewhere at the bottom of the Arno. The whole story, of course, is an invention of Dante’s. But there is fascinating drama before we get there.

5. And now for the devil’s revenge. As a complement to the spiritual/supernatural drama we witnessed with Buonconte’s death, we are presented with a nature drama that, meteorologically, is quite accurate. The devil who lost the “prize” of Buonconte’s soul to t he angel stirred up a great storm. That demons could do this was popular belief at the time. A heavy fog filled the area where Buonconte died, followed by torrential rains that flooded the region. The stream of the Archiano overflowed its banks and carried his dead body off into the Arno. In this tumult, his arms that were crossed over his chest as he died – a last pious act to accompany his contrition–came loose as the river’s “final violence” flung him through the torrent and buried him along its bottom, ma king for him a shroud from its mud and debris. Note the watery ends for Manfred, Jacopo, and Buonconte. With their deaths comes an initiation (baptism?) into eternal life and the literal washing away of their sins.

6. Whether he intended it or not, there is a subtle connection between the fact that Buonconte’s body was never found and that we know next to nothing about this poor woman who was murdered by her husband. And at the same time, we can contrast the little she t ells us about herself with the many details Manfred, Jacopo, and Bounconte gave us. She was born in Siena and at some point moved to the Maremma, a fearsome and dangerous swampy region on the western edge of Tuscany.

As might be expected, the sparse information Pia gives leaves us with a mystery that has generated a great deal of commentary over the centuries. As with so many of his characters in the Comedy, Dante must have known–in this case–much more than he’s telling us, but he’s a consummate artist by what he leaves out. Here he seems to be more interested in poetry than history. And though it’s a very small one, Pia is the first woman to have a role in the Purgatorio–in this case showing how nimble Dante is in moving from dramatic, highly-descriptive stories to this one, utterly simple and unembellished–as the British are wont to say, “without as much as a by-your-leave.”

Pia, sometimes called La Pia, according to some early accounts was the daughter of Buonincontro Guastelloni. She may have been married twice; her first husband, Baldo di Ildobrandino de’Tolomei, having died, she married Nello della Pietra de’Pannocchieschi. He was apparently a jealous husband, the Guelf lord of the Castello della Pietra in the Maremma, and Captain of the Tuscan Guelfs. Having moved there at some point in their marriage, he is said to have accused her of adultery and had her thrown to her death down a cliff from the castle in 1295. (Whether or not Pia was an adulteress, note the connection between her and Francesca in Canto 5 of the Inferno. Both were murdered by their husbands.) Some say he wanted to marry Countess Margherita degli Aldobrandeschi, the wealthy widow of Guy de Montfort. Benvenuto da Imola writes about her death this way: “This soul was a certain noble lady of Siena of the family of the Tolomei, and she was the wife of a distinguished soldier, called Lord Nello de’ Pannocchieschi de lla Pietra, and he was powerful in the coastal area controlled by Siena. One day, while they were dining and she stood for a time at a window of the palace with her maid servants, a servant, at Nello’s bidding, took her by the feet and threw her out of the window, and she died on striking the ground.” By the way, there were other stories relating to Pia’s death: e.g., that she was brought to the Maremma where the disease-laden air (malaria) led to her death; that only her husband knew how she was killed. In the end, we do not know whether she was guilty, but like the three before her, her death was violent and came quickly.

Top of page