Dante's Divine Comedy: Purgatorio

Canto XIX

Dante has another dream: this time, an ugly, misshapen woman is singing to him. Under his gaze, she becomes a beautiful Siren. He is enchanted but Virgil breaks the spell. The Angel of Zeal, guardian of the Fourth Cornice, utters the benediction, "Blessed Are They Who Mourn", wipes off the fourth P and takes the poets to the next level . In the Fifth Cornice, lie the prostrate (and praying) souls of the penitent Covetous who worshiped wealth and power above all things. The fettered spirit of Pope Adrian V (Ottobuono Fieschi) confesses his sins and asks after his niece, Alagia.

It was the hour when the diurnal heat

No more can warm the coldness of the moon,

Vanquished by Earth, or peradventure Saturn,

When geomancers their Fortuna Major

See in the orient before the dawn

Rise by a path that long remains not dim,[1]

There came to me in dreams a stammering woman,

Squint in her eyes, and in her feet distorted,

With hands dissevered and of sallow hue.[2]

I looked at her; and as the sun restores

The frigid members which the night benumbs,

Even thus my gaze did render voluble

Her tongue, and made her all erect thereafter

In little while, and the lost countenance

As love desires it so in her did color.

When in this wise she had her speech unloosed,

She 'gan to sing so, that with difficulty

Could I have turned my thoughts away from her.

"I am," she sang, "I am the Siren sweet

Who mariners amid the main unman,

So full am I of pleasantness to hear.

I drew Ulysses from his wandering way

Unto my song, and he who dwells with me

Seldom departs so wholly I content him."

Her mouth was not yet closed again, before

Appeared a Lady saintly and alert

Close at my side to put her to confusion.

"Virgilius, O Virgilius! who is this?"

Sternly she said; and he was drawing near

With eyes still fixed upon that modest one.

She seized the other and in front laid open,

Rending her garments, and her belly showed me;

This waked me with the stench that issued from it.[3]

I turned mine eyes, and good Virgilius said:

"At least thrice have I called thee; rise and come;

Find we the opening by which thou mayst enter."[4]

I rose; and full already of high day

Were all the circles of the Sacred Mountain,

And with the new sun at our back we went.

Following behind him, I my forehead bore

Like unto one who has it laden with thought,

Who makes himself the half arch of a bridge,

When I heard say, "Come, here the passage is,"

Spoken in a manner gentle and benign,

Such as we hear not in this mortal region.

With open wings, which of a swan appeared,

Upward he turned us who thus spake to us,

Between the two walls of the solid granite.[5]

He moved his pinions afterwards and fanned us,

Affirming those 'qui lugent' to be blessed,

For they shall have their souls with comfort filled.[6]

"What aileth thee, that aye to Earth thou gazest?"

To me my Guide began to say, we both

Somewhat beyond the Angel having mounted.

And I: "With such misgiving makes me go

A vision new, which bends me to itself,

So that I cannot from the thought withdraw me."

"Didst thou behold," he said, "that old enchantress,

Who sole above us henceforth is lamented?

Didst thou behold how man is freed from her?

Suffice it thee, and smite earth with thy heels,

Thine eyes lift upward to the lure, that whirls

The Eternal King with revolutions vast."

Even as the hawk, that first his feet surveys,

Then turns him to the call and stretches forward,

Through the desire of food that draws him thither,[7]

Such I became, and such, as far as cleaves

The rock to give a way to him who mounts,

Went on to where the circling doth begin.

On the fifth circle when I had come forth,

People I saw upon it who were weeping,

Stretched prone upon the ground, all downward turned.[8]

"Adbaesit pavimento anima mea,"

I heard them say with sighings so profound,

That hardly could the words be understood.[9]

"O ye elect of God, whose sufferings

Justice and Hope both render less severe,

Direct ye us towards the high ascents."[10]

"If ye are come secure from this prostration,

And wish to find the way most speedily,

Let your right hands be evermore outside."

Thus did the Poet ask, and thus was answered

By them somewhat in front of us; whence I

In what was spoken divined the rest concealed,

And unto my Lord's eyes mine eyes I turned;

Whence he assented with a cheerful sign

To what the sight of my desire implored.

When of myself I could dispose at will,

Above that creature did I draw myself,

Whose words before had caused me to take note,

Saying: "O Spirit, in whom weeping ripens

That without which to God we cannot turn,

Suspend awhile for me thy greater care.

Who wast thou, and why are your backs turned upwards,

Tell me, and if thou wouldst that I procure thee

Anything there whence living I departed."

And he to me: "Wherefore our backs the heaven

Turns to itself, know shalt thou; but beforehand

'Scias quod ego fui successor Petri.'[11]

Between Siestri and Chiaveri descends

A river beautiful, and of its name

The title of my blood its summit makes.

A month and little more essayed I how

Weighs the great cloak on him from mire who keeps it,

For all the other burdens seem a feather.

Tardy, ah woe is me! was my conversion;

But when the Roman Shepherd I was made,

Then I discovered life to be a lie.

I saw that there the heart was not at rest,

Nor farther in that life could one ascend;

Whereby the love of this was kindled in me.

Until that time a wretched soul and parted

From God was I, and wholly avaricious;

Now, as thou seest, I here am punished for it.[12]

What avarice does is here made manifest

In the purgation of these souls converted,

And no more bitter pain the Mountain has.

Even as our eye did not uplift itself

Aloft, being fastened upon earthly things,

So justice here has merged it in the earth.

As avarice had extinguished our affection

For every good, whereby was action lost,

So justice here doth hold us in restraint,

Bound and imprisoned by the feet and hands;

And so long as it pleases the just Lord

Shall we remain immovable and prostrate."[13]

I on my knees had fallen, and wished to speak;

But even as I began, and he was 'ware,

Only by listening, of my reverence,

"What cause," he said, "has downward bent thee thus?"

And I to him: "For your own dignity,

Standing, my conscience stung me with remorse."

"Straighten thy legs, and upward raise thee, brother,"

He answered: "Err not, fellow-servant am I

With thee and with the others to one power.

If e'er that holy, evangelic sound,

Which sayeth 'neque nubent,' thou hast heard,

Well canst thou see why in this wise I speak.[14]

Now go; no longer will I have thee linger,

Because thy stay doth incommode my weeping,

With which I ripen that which thou hast said.

On Earth I have a grandchild named Alagia,

Good in herself, unless indeed our house

Malevolent may make her by example,[15]

And she alone remains to me on Earth."

Illustrations of Purgatorio

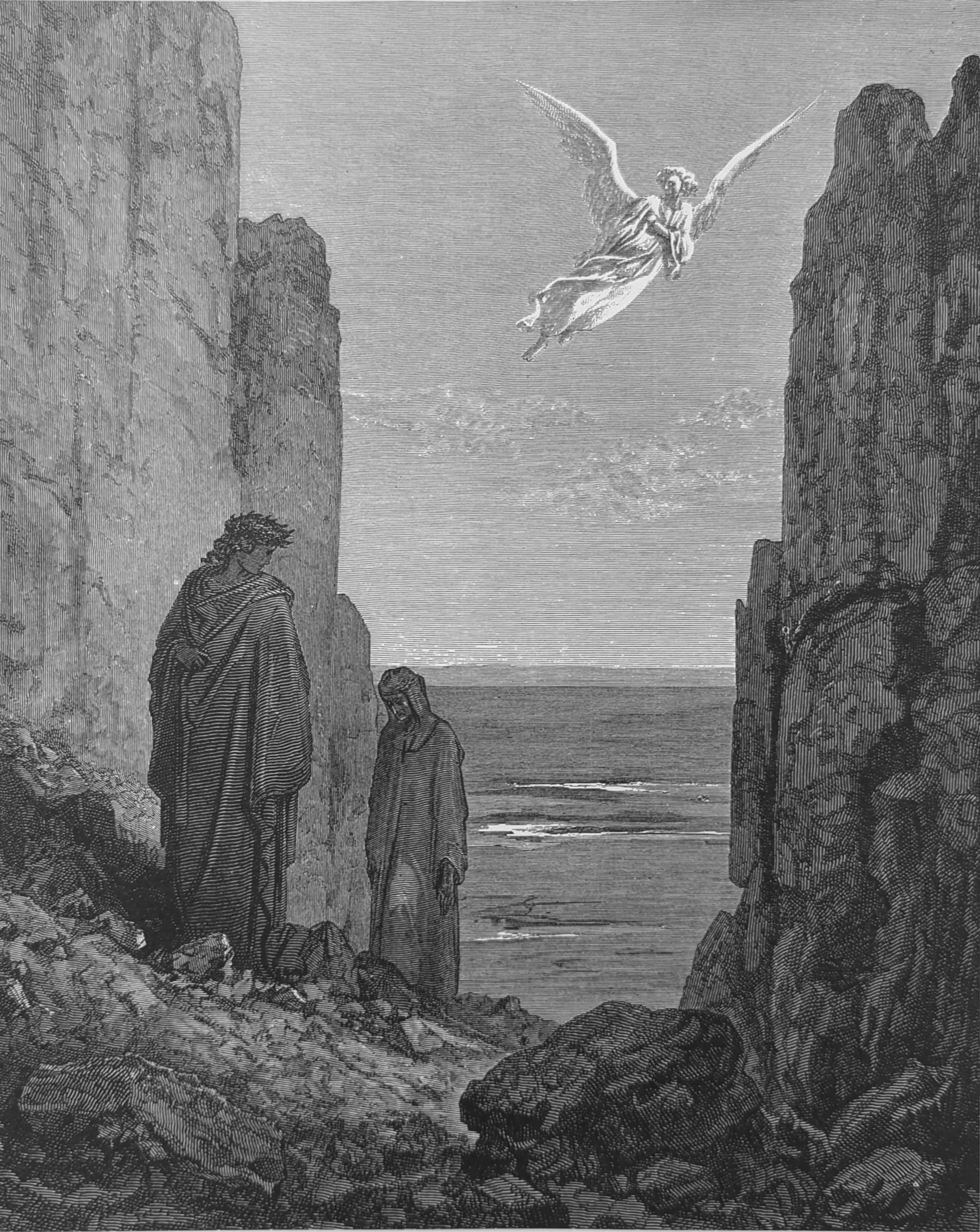

"What aileth thee, that aye to Earth thou gazest?" / To me my Guide began to say, we both / Somewhat beyond the Angel having mounted. Purg. XIX, lines 52-54

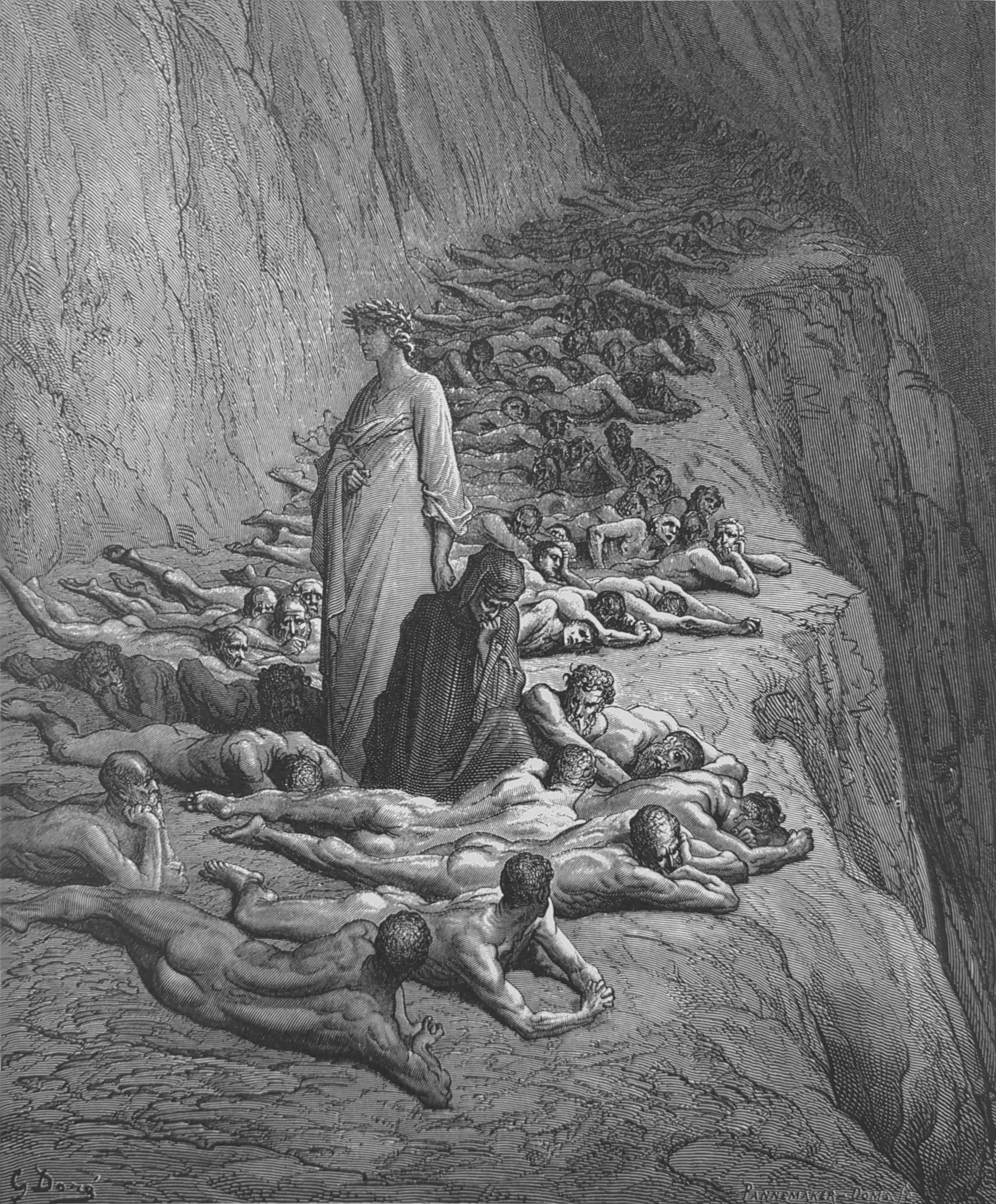

"What cause," he said, "has downward bent thee thus?" / And I to him: "For your own dignity, / Standing, my conscience stung me with remorse." Purg. XIX, lines 130-132

Footnotes

1. While Dante drops the word into his text and moves on, geomancy (practiced by geomancers) was a complex practice of divination that was very popular in Europe in the Middle Ages. Practitioners of geomancy foretold the future by attempting to match random marks on the ground or some other surface with configurations of stars. There are sixteen geomantic patterns of marks, and Fortuna Major (Greater Fortune, or good luck) is the most favorable sign in the geomantic system. It involves a pattern of the last few stars in the constellation of Aquarius and the first stars of Pisces. The pattern would look something like this:

**

**

*

*

which would/could be associated with the four prime elements (earth, air, fire, water) or parts of the body, etc. In fact, this particular pattern of stars in these two constellations would have appeared in the east before sunrise on the morning Dante write s about here.

2. First, we must remember that we are still on the Terrace of Sloth. Dante’s initial description of the Siren who appears to him in his dream needs no further explanation except that his staring at her seems to work a kind of magical transformation so that sh e becomes the exact opposite of what she first appeared to be. Observe how he stares at her and she is transformed, then she sings to him and he is almost transformed. We have here an image of the gradual seduction of the inattentive soul. Something inherently evil can gradually become falsely beautiful—and loved—if we aren’t careful, allowing ourselves to be taken in by it.

As she sings, Dante becomes her captive and she identifies herself. Ronald Martinez notes that the double “I am” is a possible parody of God’s self-identification to Moses on Mount Sinai in the Book of Exodus. In this case, we have non-being (the Siren) posing as Being Itself. Moreover, and to emphasize the danger of her power, she tells the Poet that it was her singing that led Ulysses off course into near destruction in Homer’s Odyssey (12:39-200). Of course, we know that Dante never read Homer. His resource for Ulysses, among others, was Cicero’s De Finibus (On the ends of good and evil) (5:18), where the famed Roman writes about Ulysses and the Sirens. Cicero’s point is fascinating, though, because he suggests that it wasn’t their songs that attracted and enchanted passing voyagers. Rather, it was that the Sirens possessed knowledge, and it was this knowledge “that kept men rooted to their rocky shores.” Ulysses in Homer, of course, escapes. In Cicero’s sense, and in Homer’s, Dante is like their Ulysses. He is in search of the ultimate knowledge—salvation, and he is a traveler on an epic journey. In both cases, he needs to keep his wits about him and focus clearly on his goal. Recall that he refers, at times, to his Poem as a ship, and he (the soul) needs to navigate the waters of life carefully.

3. Contrary to the Siren, the “saintly lady” is not identified, though she is definitely heaven-sent. She sharply summons Virgil (symbolizing Reason) to rescue Dante who was being seduced by the Siren’s outward beauty. He, in turn, rushes forward, boldly tears open the Siren’s clothes, and reveals the horror of her ugliness–evil and sin symbolized by the terrible stench. Note that during this wild scene, Virgil never takes his eyes off the saintly lady. In a sense, she is his protection from what has just happen ed to Dante.

4. There is something to be said about Virgil’s three calls to awaken Dante from his dream. The Poet may have had in mind that pivotal scene in the Garden of Gethsemane just before Jesus’ arrest (Mt 26:36-46). Three times he left his disciples to go off and pray by himself. Three times he came back and woke them because they had fallen asleep. Finally rousing them from their slumber he says: “Get up, let us go. Look, my betrayer is at hand.” Jesus was betrayed by Judas, one of the disciples who had been part of his inner group. Likewise, Dante was in the process of betrayal by the Siren.

5. The first to speak, though, is not Virgil. It’s the Angel of Zeal. That he speaks in tones not heard on earth is a waking spiritual reminder, after last night’s dream, that the soul, on the path to salvation, must ever strive to be in tune with the voice of virtue rather than the voice of evil. Waving its beautiful wings over them, the angel shows them the stairs and anticipates the punishment on the next terrace with a line from the Beatitudes in St. Matthew’s Gospel (5:4): “Blessed are those who mourn, for they will be comforted.” At the same time, this verse is subtly fitting as we leave the Terrace of Sloth.

6. qui lugent, Latin, "those who mourn".

7. Urging Dante to look upward and be enthralled by the heavens, Virgil spurs Dante to think of himself as a falcon (hawk) at rest and then released to fly after its prey. It returns when the falconer whirls his lure. Virgil is really telling Dante to look up instead of down and be enthralled by God the Falconer who whirls his own lures–-the heavens above–-and draws him upward to Paradise (and through the rest of Purgatory) where he will dine on everlasting food.

8. Emerging from the narrow stairway, Dante arrives at the Terrace of Avarice. Looking around, he sees penitent, weeping souls, lying everywhere, face-down on the ground. At the same time, he hears their muffled singing from Psalm 119, verse 25: “My soul cling s to the dust.” Over the years, commentaries on this verse have presented it as a warning against worldly attachments, and the conjoined word, adhaesit pavimento, came to be the term used for the posture of a person laying on the ground in a prayer of sup plication.

9. Adbaesit pavimento anima mea, Latin, "My soul has stuck to the pavement".

10. It is Virgil who speaks first here, and with great respect. These are the same words he used to address the crowd of souls he and Dante encountered in Canto 3 as they were looking for the place to begin climbing the Mountain. That Virgil mentions the justice and hope that make the souls’ suffering easier here may be a reflection of his and the other souls’ condition in Limbo, which is quite the opposite—so notes Robert Hollander. There they long for what these souls are assured of—“… hope in the justice of God for eventual salvation.”

11. Scias quod ego fui successor Petri, Latin, "You should know that I was the successor of Peter".

Before the speaker begins to answer Dante’s questions, he tells him in Latin that he was the successor of Peter. He is the soul of Pope Adrian V. The cities he mentions that were connected with his family indicate that he was of the noble family of the Fieschi in Genoa and the Counts of Lavagna (also the name of the river that flows between Sestri and Chiaveri). Before he became Pope he had been made a cardinal by his uncle, Innocent IV, and acted as a papal legate to England, restoring peace among the warring barons. He also preached the Crusade of 1270. He was elected Pope on July 11, 1276 (Dante would have been 11 years old) and died 38 days later on August 18.

Remarking rather pointedly on “the great mantle,” Robert Hollander notes here: “It is perhaps by design that the first saved pope whom we meet in the poem (there will be more) should be distinguished by having died shortly after his election and thus without having served ‘officially’ at all.” And note how, in Canto 19 of the Inferno, Pope Nicholas also referred to “the great mantle.”

12. Pope Adrian’s candor here is truly redemptive, and his humble admission of the earlier state of his soul is evidence that his purgation on this terrace is working effectively. His restless heart and his striving for more is an echo of St. Augustine’s famous invocation: “You have made us for yourself, and our hearts are restless until they rest in you” (Confessions 1:1). At the same time, Charles Singleton writes in his commentary that:

“No historical evidence has been found to bear out either Pope Adrian’s avarice or his conversion in so brief a time in office. Dante appears to have attributed to Adrian V words which John of Salisbury had put in the mouth of Pope Adrian IV (1154-59). In Policraticus VIII, 23, 814b-c, John of Salisbury writes: ‘He said that the chair of Peter was very uncomfortable; the cope is completely studded with spikes, and it is of such a weight that it presses upon, wears away, and breaks down even the strongest shoulders.’ He continues: ‘… as he rose, step by step, from cloistered monk through various positions until he finally became pope, his rise never added one whit to the happiness or peace of his former life.’ The passage in the Policraticus was known to Dante by an indirect tradition, even as it was to Petrarch, who at first made the same confusion of the two popes, but later corrected it.”

13. Now Pope Adrian explains the nature of the punishment meted out on this terrace. Earlier, in Canto 13, we encountered sinners with their eyes sewn shut, purging the sin of envy–-a sin of the eyes. Avarice, as Pope Adrian describes it is, in a sense, also a sin of the eyes. We see the material things of this world in a way that blinds us to their inner good, and we forget to look up to God, the Author of all created things. The sinners’ continual, almost blind, grasping for more is countered here on this terrace by the ropes is justice, and because they failed to look upward to acknowledge the beneficence of God, they are now forced to lie face down on the ground. Thus the contrapasso.

14. neque nubent, Latin, "nor do they marry".

15. Interestingly enough, Alagia was married to Moroello Malaspina, a nobleman and friend of Dante’s in the Lunigiana region to the west of Florence. He invited Dante to stay with him in the early years of his exile, as noted by Boccaccio and several other earl y commentators on Dante. In his Life of Dante, Boccaccio relates that after Dante was condemned, his family gathered a cache of important papers and documents and put them away safely. Later, when the political strife in Florence had abated somewhat, Dante’ s wife, Gemma, sent her nephew, Andrea, to get the box containing her husband’s papers. Among them he found the first seven cantos of the Inferno. Andrea gave these to a scholar named Dino Frescobaldi who, in turn, passed them along to Moroello Malaspina, begging him to press Dante into finishing what he had begun before his exile. It is said that Dante was stunned when presented with his work, saying that he believed he would never have seen it again. Thereupon, he took up the work at the eighth Canto. Obviously, this last part of Canto 19 is intended by Dante as a tribute to Moroello and his wife, Alagia. In a sense, it is thanks to Moroello that we have the Divine Comedy!

Top of page