Dante's Divine Comedy: Purgatorio

Canto XX

As the two poets make their way through the Fifth Cornice, they hear someone proclaiming examples of the virtue opposed to Covetousness. The voice cites Mary, Fabricius and Saint Nicholas. This spirit is Hugh Capet, founder of the Capetian dynasty. He goes on to denounce the crimes of his descendants. Speaking of the souls, be explains that they recite virtuous prayers by day but at night they engage in criticism of the covetousness of prominent figures such as Pygmalion and Midas. The travelers carry on wit h their journey until the mountain of Purgatory suddenly shakes from top to bottom. All the prostrate souls sing Gloria in excelsis Deo. Dante is intrigued.

Ill strives the will against a better will;

Therefore, to pleasure him, against my pleasure

I drew the sponge not saturate from the water.

Onward I moved, and onward moved my Leader,

Through vacant places, skirting still the rock,

As on a wall close to the battlements;

For they that through their eyes pour drop by drop

The malady which all the world pervades,

On the other side too near the verge approach.

Accursed mayst thou be, thou old she-wolf,

That more than all the other beasts hast prey,

Because of hunger infinitely hollow![1]

O heaven, in whose gyrations some appear

To think conditions here below are changed,

When will he come through whom she shall depart?

Onward we went with footsteps slow and scarce,

And I attentive to the shades I heard

Piteously weeping and bemoaning them;

And I by peradventure heard "Sweet Mary!"

Uttered in front of us amid the weeping

Even as a woman does who is in child-birth;[2]

And in continuance: "How poor thou wast

Is manifested by that hostelry

Where thou didst lay thy sacred burden down."

Thereafterward I heard: "O good Fabricius,

Virtue with poverty didst thou prefer

To the possession of great wealth with vice."

So pleasurable were these words to me

That I drew farther onward to have knowledge

Touching that spirit whence they seemed to come.

He furthermore was speaking of the largess

Which Nicholas unto the maidens gave,

In order to conduct their youth to honor.

"O soul that dost so excellently speak,

Tell me who wast thou," said I, "and why only

Thou dost renew these praises well deserved?

Not without recompense shall be thy word,

If I return to finish the short journey

Of that life which is flying to its end."

And he: "I'll tell thee, not for any comfort

I may expect from earth, but that so much

Grace shines in thee or ever thou art dead.

I was the root of that malignant plant

Which overshadows all the Christian world,

So that good fruit is seldom gathered from it;[3]

But if Douay and Ghent, and Lille and Bruges

Had Power, soon vengeance would be taken

And this I pray of Him who judges all.

Hugh Capet was I called upon the Earth;

From me were born the Louises and Philips,

By whom in later days has France been governed.[4]

I was the son of a Parisian butcher,

What time the ancient kings had perished all,

Excepting one, contrite in cloth of gray.

I found me grasping in my hands the rein

Of the realm's government, and so great power

Of new acquest, and so with friends abounding,

That to the widowed diadem promoted

The head of mine own offspring was, from whom

The consecrated bones of these began.[5]

So long as the great dowry of Provence

Out of my blood took not the sense of shame,

Twas little worth, but still it did no harm.

Then it began with falsehood and with force

Its rapine; and thereafter, for amends,

Took Ponthieu, Normandy, and Gascony.[6]

Charles came to Italy, and for amends

A victim made of Conradin, and then

Thrust Thomas back to heaven, for amends.[7]

A time I see, not very distant now,

Which draweth forth another Charles from France,

The better to make known both him and his.[8]

Unarmed he goes, and only with the lance

That Judas jousted with; and that he thrusts

So that he makes the paunch of Florence burst.

He thence not land, but sin and infamy,

Shall gain, so much more grievous to himself

As the more light such damage he accounts.

The other, now gone forth, ta'en in his ship,

See I his daughter sell, and chaffer for her

As corsairs do with other female slaves.[9]

What more, O Avarice, canst thou do to us,

Since thou my blood so to thyself hast drawn,

It careth not for its own proper flesh?

That less may seem the future ill and past,

I see the flower-de-luce Alagna enter,

And Christ in his own Vicar captive made.

I see him yet another time derided;

I see renewed the vinegar and gall,

And between living thieves I see him slain.

I see the modern Pilate so relentless,

This does not sate him, but without decretal

He to the temple bears his sordid sails!

When, O my Lord! shall I be joyful made

By looking on the vengeance which, concealed,

Makes sweet thine anger in thy secrecy?

What I was saying of that only bride

Of the Holy Ghost, and which occasioned thee

To turn towards me for some commentary,

So long has been ordained to all our prayers

As the day lasts; but when the night comes on,

Contrary sound we take instead thereof.

At that time we repeat Pygmalion,

Of whom a traitor, thief, and parricide

Made his insatiable desire of gold;[10]

And the misery of avaricious Midas,

That followed his inordinate demand,

At which forevermore one needs but laugh.[11]

The foolish Achan each one then records,

And how he stole the spoils; so that the wrath

Of Joshua still appears to sting him here.[12]

Then we accuse Sapphira with her husband,

We laud the hoof-beats Heliodorus had,

And the whole mount in infamy encircles[13]

Polymnestor who murdered Polydorus.

Here finally is cried: 'O Crassus, tell us,

For thou dost know, what is the taste of gold?'[14]

Sometimes we speak, one loud, another low,

According to desire of speech, that spurs us

To greater now and now to lesser pace.

But in the good that here by day is talked of,

Erewhile alone I was not; yet near by

No other person lifted up his voice."

From him already we departed were,

And made endeavor to o'ercome the road

As much as was permitted to our power,

When I perceived, like something that is falling,

The mountain tremble, whence a chill seized on me,

As seizes him who to his death is going.[15]

Certes so violently shook not Delos,

Before Latona made her nest therein

To give birth to the two eyes of the heaven.[16]

Then upon all sides there began a cry,

Such that the Master drew himself towards me,

Saying, "Fear not, while I am guiding thee."

"Gloria in excelsis Deo," all

Were saying, from what near I comprehended,

Where it was possible to hear the cry.

We paused immovable and in suspense,

Even as the shepherds who first heard that song,

Until the trembling ceased, and it was finished.

Then we resumed again our holy path,

Watching the shades that lay upon the ground,

Already turned to their accustomed plaint.

No ignorance ever with so great a strife

Had rendered me importunate to know,

If erreth not in this my memory,

As meditating then I seemed to have;

Nor out of haste to question did I dare,

Nor of myself I there could aught perceive;

So I went onward timorous and thoughtful.

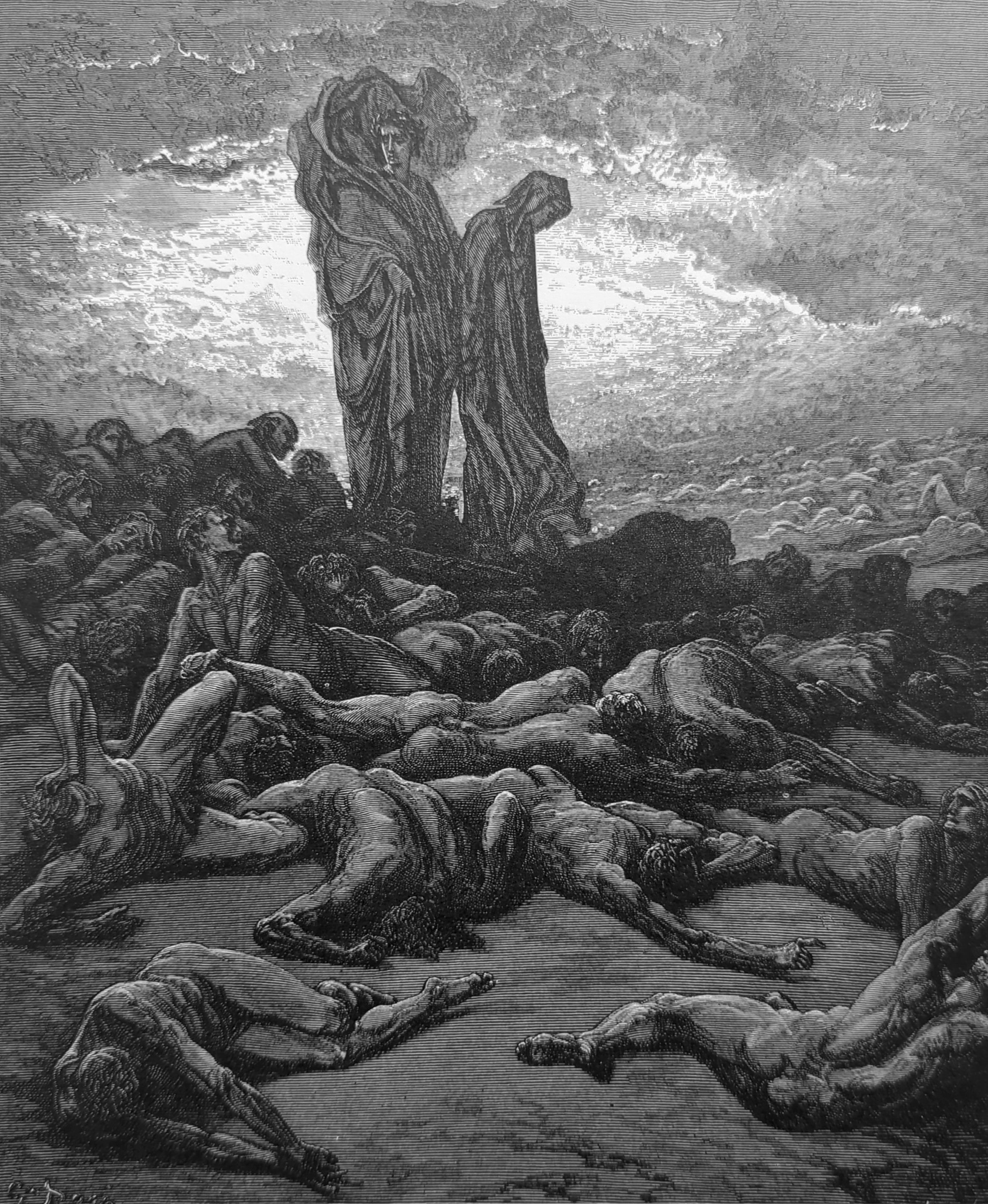

Illustrations of Purgatorio

Onward we went with footsteps slow and scarce, / And I attentive to the shades I heard / Piteously weeping and bemoaning them; Purg. XX, lines 16-18

Footnotes

1. These lines are rich with allusions to Canto 1 of the Inferno. First is the ancient She-Wolf, the third of the wild beasts that sent Dante running down the mountainside and back into the dark forest. Vicious and hungry, she symbolizes the ravenous greed that has been the downfall of so many. It is the same here as Dante apostrophizes the sin of greed. And raising his voice to the heavens for some divine intervention, “that one to come” is a reference to the Greyhound–-also in Canto 1 of the Inferno–-who will drive the wolf away and heal the world of greed. The Poet’s curse of the She-Wolf is reminiscent of Virgil’s rebuke of Plutus, early in Canto 7 of the Inferno: “Be quiet, cursed wolf of Hell: feed on the burning bile that rots your guts.” Plutus is the god of wealth and guardian of the circle of the misers and hoarders.

2. Here we have three examples of poverty and generosity as the “whip” of avarice. In keeping with the pattern of these examples of virtue, the first refers to the Virgin Mary who was so poor that she gave birth to Jesus–the Son of God–in a stable. Note that t he voice that cries out this example actually sounds like a woman about to give birth. The second example is from Roman history. Gaius Fabricius Luscinus, a general and consul who spurned a life of greed and luxury, and later refused to be bribed in exchange for betraying Rome. Though a hero, he eventually died in such poverty that he had to be buried by the state. And the third example comes from the story of St. Nicholas, a wealthy fourth-century bishop of Myra in Turkey during the reign of Constantine. He gave away his money to the poor. Known to us as “Santa Claus,” he saved the three young daughters of an impoverished friend from lives of prostitution because they were too poor to marry. One night he threw bags of gold through their window so that they would have dowries and be able to marry respectably. Thus the tradition of filling stockings on the night before Christmas. Another tradition has it that the three gold balls over a pawn shop’s door represent St. Nicholas’ three bags of gold. And in Medieval heraldry, the three gold balls represented wealth and prosperity.

3. This as-yet-unidentified soul begins speaking with a reply that evinces the progress of his penitence for the sin of avarice. He doesn’t seek something for himself, namely, Dante’s offer of a “reward.” Rather, he graciously acknowledges the action of God’s grace in the fact that Dante is standing there alive and speaking with him. Furthermore, he senses the goodness within Dante, which is also evidence of God’s activity. Building obliquely–-and opaquely-–toward the revelation of his identity, this soul first presents a negative image of himself as the root (as we shall see) of an evil family tree whose branches cover and darken all of Europe and the Near East, and stifle mu ch good growth beneath them.

The mention of the four chief cities of Flanders is an allusion to the wars of the treacherous King Philip IV (the Fair) against Flanders. The French were finally defeated by the Flemish forces (this “the vengeance that is theirs”) at the Battle of Courtrai (also known as the Battle of the Golden Spurs) in 1302. Since the Poem is set in 1300, this “wish” is more of a prophecy here.

4. At last, the speaker identifies himself as the founder of the Capaetian Dynasty in France. But, as will be pointed out below, there was most likely confusion on Dante’s part as to which Hugh Capet he was actually referring to. That he was the father of kings is borne out by the fact that all the kings of France from 1060 to 1300 (the year in which this Poem is set) were either Philips or Louises. Many of their nicknames have stayed with them throughout history: “the Fat,” “the Young,” “Augustus,” “the Lion,” “the Saint,” “the Bold,” “the Slothful,” “the Fair,” etc. When he notes that these kings ruled France “to this very day,” Dante is undoubtedly referring to the evil Philip IV (“the Fair”), whose brother, Charles of Valois, betrayed the Florentine White Guelphs (Dante) into the hands of the Black Guelphs in 1301. Robert Hollander notes here that of the ten kings who followed Hugh to the throne between 996 and 1314, four of them bore the name “Philip” and four “Louis.” But it is the last in each of these groups who may be of greatest interest. “Louis IX (1225-1270) is one of the major figures of the Middle Ages, a great crusader, king, and saint. Of him Dante is-–perhaps not surprisingly, given his hatred of France–-resolutely silent; of Philip IV (the Fair: 1285-1314), he is loquacity itself, vituperating him several times in this canto, but also in a number of other passages [in all three Canticles of the Poem].”

5. Diadem, Latin, diadēma, an ornamental headband worn as a badge of royalty.

6. As for Ponthieu, Normandy, and Gascony, all three of these were English territories. Philip II took Normandy in 1202, and in 1292 Ponthieu and Gascony were taken by Philip IV (the Fair).

7. Charles of Anjou was called to Italy after Manfred, King of Sicily, had been excommunicated (see Purg. 3). Charles became king in his place, but Manfred did not go easily. Unfortunately, he was defeated and killed by the forces of Charles at the Battle of Benevento in 1266. Manfred’s nephew and rightful heir, Conradin, was later defeated and beheaded by Charles.

Hugh tells Dante that Charles of Anjou also poisoned St. Thomas Aquinas, the most brilliant theologian of the Middle Ages. Actually, this was a legend in Dante’s day but it is completely unfounded. According to the story, Aquinas knew some grave secret about Charles that he was going to reveal. Thus the poisoning. The author of the Anonimo Fiorentino notes that before he left for Lyons, Aquinas was asked by Charles what he would say if anyone asked about him. Aquinas said that he would tell the truth. Shortly after he left, Charles sent two doctors to catch up with him, apparently with poison. Telling Thomas that they were sent by Charles to attend to his safety during his journey to Lyons, they later poisoned him with some medication. According to Robert Hollander, this was “a rumor that appears to have been made out of whole cloth as part of Italian anti-French propaganda, but which Dante seems only too willing to propagate.” As for the truth, Aquinas had been summoned from Naples to the Second Council of Lyons by Pope Gregory X . On the way, he apparently hit his head on a large tree branch near Monte Cassino. Recovering, he continued on his way, but later became ill because of the wound to his head and stopped at the Trappist monastery in Fossanova between Naples and Rome. It was there that he later died (March 7, 1274), apparently from a swelling of the brain.

8. In this prophecy Hugh is referring this time to Charles of Valois, brother of Philip IV (the Fair). In terms of how “he and his family behave,” the outcome is not good. In 1301, he came to Italy with the intention of recovering the Kingdom of Sicily for France. Already in thrall to Pope Boniface VIII (Dante’s nemesis), he came to Florence as a supposed peace-maker (intending to destroy those who opposed Boniface’s expansionist-–read Florence-–policies). Instead, he backed the coup whereby the Florentine Black Guelphs ousted the White Guelphs (Dante’s party) and with this betrayal thrust “the spear of Judas … into the belly of Florence!” This led to Dante’s exile. Of this event, Benvenuto da Imola writes: “In that time Florence had grown fat, full of citizens an d bursting with pride. And this Charles ripped her belly open so that he made her guts burst out, that is to say, her principal citizens, among whom was this famous poet.”

Charles’ “reward” of shame for this treachery was that he lost Sicily and ended up with the nickname “Lackland.” His countrymen jeered: “… son of a king, brother of a king, uncle of three kings, father of a king, but never a king.” Charles Singleton notes h ere: “…he unsuccessfully aspired to no less than four crowns: those of Aragon, of Sicily, of Constantinople (through his second wife, Catherine, daughter of Philip de Courtenay, titular emperor of Constantinople), and of the Empire.”

And, finally, accepting “no blame for his wicked deeds” is, according to Mark Musa here: “… significant because in this canto assuming personal responsibility becomes an issue, the individual penitent taking charge of his own atonement.”

9. This third Charles (the Lame) is Charles II, King of Naples and son of Charles of Anjou. Hugh is referring to an incident during the war of the “Sicilian Vespers,” where Charles, against the orders of his father, set out to engage the fleet of Peter III of Aragon near Palermo. Charles’ forces were defeated and he was taken prisoner. Hundreds of his retainers were captured with him and executed in revenge for the murder of Conradin by Charles’ father, Charles of Anjou, after the defeat and death of King Manfred of Sicily at the Battle of Benevento.

Highlighting his greedy sins, Hugh recalls a deplorable act where, like a pirate, this Charles shamelessly married his youngest daughter, Beatrice, to the cruel Azzo VIII d’Este (reputed by Dante in Inf. 18 for having murdered his father) for an enormous sum (51,000 florins). Hugh’s brief apostrophe against Avarice is that of a grief-stricken father whose heirs “care nothing for their own children.” It echoes the earlier curse(s) against the greedy she-wolf and mirrors Aeneas’ curse as he mourns the death of Polydorus: “To what do you not drive human breasts, O cursed hunger for gold” (Aeneid 3:56f).

10. The first wicked example of avarice is Pygmalion, taken from Virgil’s Aeneid. (This is not the Greek Pygmalion who fell in love with a statue.) He was the king of Tyre and brother of Dido, queen of Carthage (and lover of Aeneas). Pygmalion murdered Dido’s wealthy husband, Sychaeus, in order to steal his wealth. But he was foiled in this when Sychaeus appeared in a dream to Dido and exposed the plot, enabling her to escape with her dead husband’s wealth.

Parricide, someone who kills a relative, especially a parent.

11. The next example refers to the famous story of King Midas of Phrygia in Ovid’s Metamorphoses. Having done a favor for Bacchus, he was granted one wish. Being so in love with gold, he asked that everything he touched would be turned to gold. This became a problem when he sat down to eat, and he was forced to ask that his wish be reversed.

12. The third example is from the Book of Joshua in the Old Testament. When the ancient city of Jericho was captured and destroyed by Joshua and his army, Joshua commanded that any valuables recovered afterward were to be collected and consecrated to God. Achan disobeyed Jericho and took some of the loot for himself. As a result, he and his family were stoned to death.

13. The fourth (and fifth) example comes from the Acts of the Apostles in the New Testament. The early Christian converts in Jerusalem formed a kind of commune in which they held all things in common. Ananias and his wife, Sapphira, sold some property but gave only part of the proceeds to the Apostles saying it was all. Their lie was uncovered and they fell dead at the feet of St. Peter.

The next example comes from the Second Book of Maccabees in the Old Testament. There, Heliodorus, the chief minister of King Seleucus, went to rob the treasury of the Temple in Jerusalem for the king. But he was stopped by the appearance of a terrifying divine figure clad in golden armor and mounted on a great horse who rushed at him and kicked him with his front feet. Then two strong men appeared and beat him senseless.

14. The seventh example is also from the Aeneid and involves the story of Polymnestor, the King of Thrace. In order to save his youngest son, Polydorus, from the war, Priam, King of Troy, sent his son to Polymnestor for protection with a great sum of gold. When Troy fell, Polymnestor murdered Polydorus and kept the gold.

The last example is presented sarcastically by Hugh and involves Crassus, known as the richest man in Rome, who joined with Julius Caesar and Pompey in the First Triumverate. Later, as governor of Syria he waged war against the Parthian Empire and was defeated. Killed in battle and beheaded, his head was delivered to the Parthian king, Hyrodes. Knowing his love for gold, the king poured molten gold down his throat, saying: “You thirsted for gold, drink gold!”

15. And from the murmuring of the penitents here it shocks Dante into a new reality about the Mountain of Purgatory that will be revealed in the next canto. Furthermore, the terrifying earthquake, during which Dante fears he will die, is accompanied by a shout from every soul on the Mountain. The point Dante wants to make here is that if the shepherds in the Bethlehem hills were stunned into something totally new by the heavens opening and the angels singing Gloria at the birth of Jesus (Luke 3:15), he and Virgil (and the reader) are likewise ushered into a new (apocalyptic?) reality about the nature of Purgatory, a reality we can look forward to with much anticipation because the entire Poem is only half over.

16. The mention of the Greek island of Delos also adds a mythical flavor to this experience. Latona was pregnant by Jupiter, and fled from place to place, chased his jealous wife, Juno. To protect her (according to one version of the story), Jupiter caused a gr eat earthquake and raised the island of Delos out of the sea and stabilized it. (It is the smallest of a chain of islands called the Cyclades off the southeast of the mainland of Greece. The word “Cyclades” means to encircle, and the sacred island of Delos sits in the middle of a group of more than 200 other islands.) Latona went there and gave birth to the twins Apollo and Diana-–the Sun and the Moon. (We know from both ancient and modern history that that area of the Mediterranean world is often rocked by powerful earthquakes.)

Top of page