Dante's Divine Comedy: Purgatorio

Canto XXIX

The first allegorical masque, the triumphant Pageant of the Sacrament, draws near. A company dressed in white, like a Corpus Christi procession, is carrying seven candlesticks (the gifts of the Holy Spirit), followed by twenty-four elders crowned with lilies (the books of the Old Testament) and four winged creatures (the Beasts of the Apo calypse). Its centrepiece is a chariot pulled by a Griffin (half-eagle/half-lion and, as such, the union of Christ's divine and human nature) with three damsels (the Theological Virtues) on the right and four (the Cardinal Virtues) on the left. Behind every one is an old man (the Book of the Revelation of Saint John).[1]

Singing like unto an enamoured lady

She, with the ending of her words, continued:

"Beati quorum tecta sunt peccata."[2]

And even as Nymphs, that wandered all alone

Among the sylvan shadows, sedulous

One to avoid and one to see the sun,[3]

She then against the stream moved onward, going

Along the bank, and I abreast of her,

Her little steps with little steps attending.[4]

Between her steps and mine were not a hundred,

When equally the margins gave a turn,

In such a way, that to the East I faced.

Nor even thus our way continued far

Before the lady wholly turned herself

Unto me, saying, "Brother, look and listen!"[5]

And lo! a sudden lustre ran across

On every side athwart the spacious forest,

Such that it made me doubt if it were lightning.

But since the lightning ceases as it comes,

And that continuing brightened more and more,

Within my thought I said, "What thing is this?"[6]

And a delicious melody there ran

Along the luminous air, whence holy zeal

Made me rebuke the hardihood of Eve;

For there where Earth and heaven obedient were,

The woman only, and but just created,

Could not endure to stay 'neath any veil;

Underneath which had she devoutly stayed,

I sooner should have tasted those delights

Ineffable, and for a longer time.

While 'mid such manifold first-fruits I walked

Of the eternal pleasure all enrapt,

And still solicitous of more delights,

In front of us like an enkindled fire

Became the air beneath the verdant boughs,

And the sweet sound as singing now was heard.

O Virgins sacrosanct! if ever hunger,

Vigils, or cold for you I have endured,

The occasion spurs me their reward to claim!

Now Helicon must needs pour forth for me,

And with her choir Urania must assist me,

To put in verse things difficult to think.[7]

A little farther on, seven trees of gold

In semblance the long space still intervening

Between ourselves and them did counterfeit;[8]

But when I had approached so near to them

The common object, which the sense deceives,

Lost not by distance any of its marks,

The faculty that lends discourse to reason

Did apprehend that they were candlesticks,

And in the voices of the song "Hosanna!"

Above them flamed the harness beautiful,

Far brighter than the moon in the serene

Of midnight, at the middle of her month.

I turned me round, with admiration filled,

To good Virgilius, and he answered me

With visage no less full of wonderment.[9]

Then back I turned my face to those high things,

Which moved themselves towards us so sedately,

They had been distanced by new-wedded brides.

The lady chid me: "Why dost thou burn only

So with affection for the living lights,

And dost not look at what comes after them?"

Then saw I people, as behind their leaders,

Coming behind them, garmented in white,

And such a whiteness never was on Earth.

The water on my left flank was resplendent,

And back to me reflected my left side,

E'en as a mirror, if I looked therein.[10]

When I upon my margin had such post

That nothing but the stream divided us,

Better to see I gave my steps repose;

And I beheld the flamelets onward go,

Leaving behind themselves the air depicted,

And they of trailing pennons had the semblance,

So that it overhead remained distinct

With sevenfold lists, all of them of the colours

Whence the sun's bow is made, and Delia's girdle.[11]

These standards to the rearward longer were

Than was my sight; and, as it seemed to me,

Ten paces were the outermost apart.

Under so fair a heaven as I describe

The four and twenty Elders, two by two,

Came on incoronate with flower-de-luce.[12]

They all of them were singing: "Blessed thou

Among the daughters of Adam art, and blessed

For evermore shall be thy loveliness."

After the flowers and other tender grasses

In front of me upon the other margin

Were disencumbered of that race elect,

Even as in heaven star followeth after star,

There came close after them four animals,

Incoronate each one with verdant leaf.[13]

Plumed with six wings was every one of them,

The plumage full of eyes; the eyes of Argus

If they were living would be such as these.[14]

Reader! to trace their forms no more I waste

My rhymes; for other spendings press me so,

That I in this cannot be prodigal.

But read Ezekiel, who depicteth them

As he beheld them from the region cold

Coming with cloud, with whirlwind, and with fire;[15]

And such as thou shalt find them in his pages,

Such were they here; saving that in their plumage

John is with me, and differeth from him.

The interval between these four contained

A chariot triumphal on two wheels,

Which by a Griffin's neck came drawn along;[16]

And upward he extended both his wings

Between the middle list and three and three,

So that he injured none by cleaving it.

So high they rose that they were lost to sight;

His limbs were gold, so far as he was bird,

And white the others with vermilion mingled.[17]

Not only Rome with no such splendid car

E'er gladdened Africanus, or Augustus,

But poor to it that of the Sun would be,--

That of the Sun, which swerving was burnt up

At the importunate orison of Earth,

When Jove was so mysteriously just.

Three maidens at the right wheel in a circle

Came onward dancing; one so very red

That in the fire she hardly had been noted.

The second was as if her flesh and bones

Had all been fashioned out of emerald;

The third appeared as snow but newly fallen.[18]

And now they seemed conducted by the white,

Now by the red, and from the song of her

The others took their step, or slow or swift.

Upon the left hand four made holiday

Vested in purple, following the measure

Of one of them with three eyes in her head.[19]

In rear of all the group here treated of

Two old men I beheld, unlike in habit,

But like in gait, each dignified and grave.[20]

One showed himself as one of the disciples

Of that supreme Hippocrates, whom nature

Made for the animals she holds most dear;

Contrary care the other manifested,

With sword so shining and so sharp, it caused

Terror to me on this side of the river.

Thereafter four I saw of humble aspect,

And behind all an aged man alone

Walking in sleep with countenance acute.

And like the foremost company these seven

Were habited; yet of the flower-de-luce

No garland round about the head they wore,

But of the rose, and other flowers vermilion;

At little distance would the sight have sworn

That all were in a flame above their brows.

And when the car was opposite to me

Thunder was heard; and all that folk august

Seemed to have further progress interdicted,

There with the vanward ensigns standing still.[21]

Illustrations of Purgatorio

The four and twenty Elders, two by two, / Came on incoronate with flower-de-luce. Purg. XXIX, lines 83-84

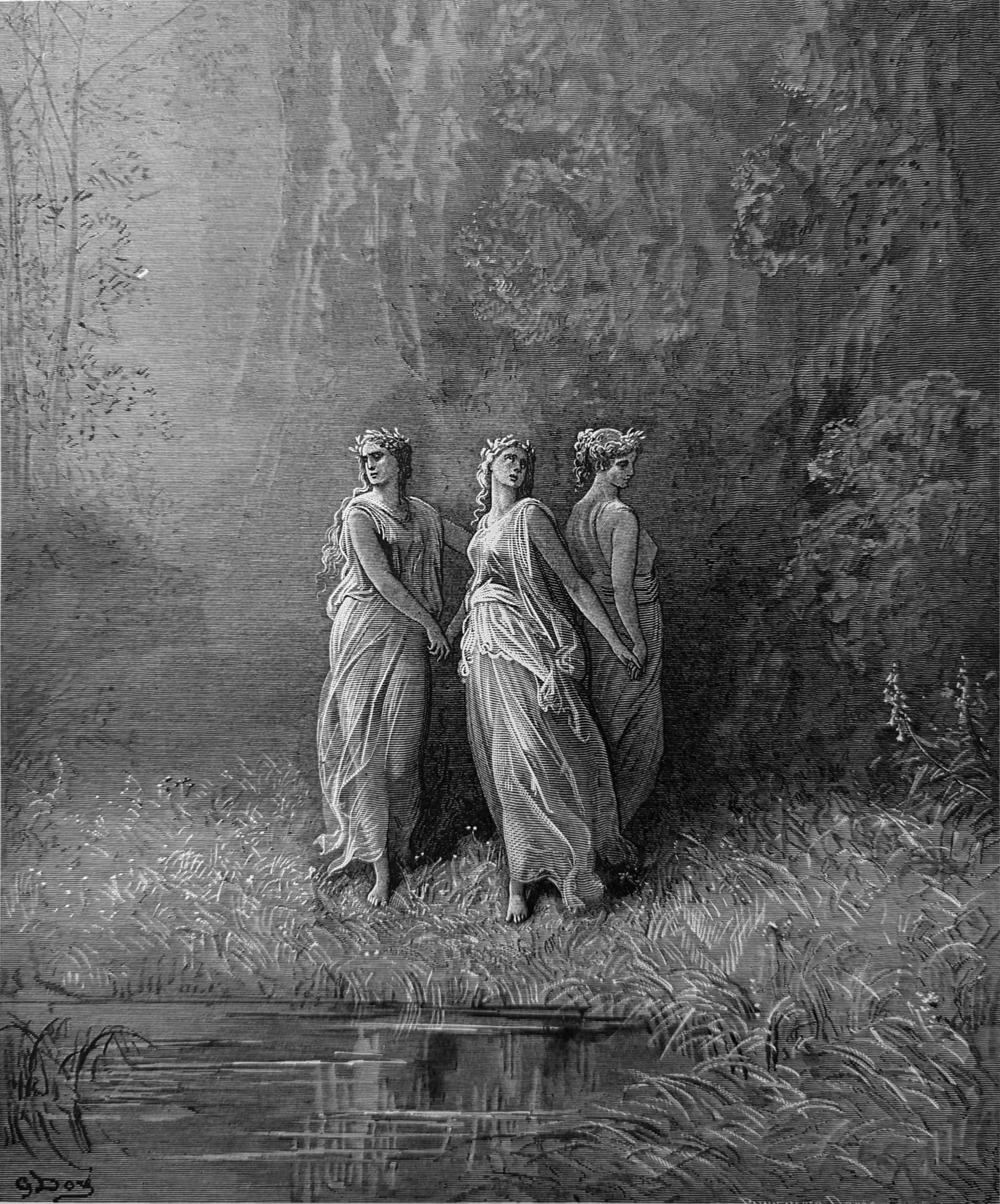

Came onward dancing; one so very red / That in the fire she hardly had been noted. / The second was as if her flesh and bones / Had all been fashioned out of emerald; / The third appeared as snow but newly fallen. Purg. XXIX, lines 122-126

Footnotes

1. Virtues:

Theological Virtues

1. Faith

2. Hope

3. Charity (Love)

Cardinal Virtues

1. Prudence

2. Justice

3. Fortitude (Courage)

4. Temperance

2. Beati quorum tecta sunt peccata, Latin, "Blessed are those whose sins are covered".

3. sedulous, Latin, sēdulus, “diligent, industrious, solicitous; unremitting”.

4. Having answered all of Dante’s questions in the previous canto, Matelda sings the first verse from Psalm 32: “Blessed is the one whose fault is removed, whose sin is forgiven.” Starting with Dante’s first encounter with Matelda in the previous canto, commen tators remark on the tender and gentle nature of Matelda and raise the question of whether or not Dante feels himself to be “in love” with her, particularly since she represents the kind of woman often the subject of love poems in the “sweet new style,” of which he is its greatest exponent. We read here that she is “moved by love.” But as Robert Hollander notes in his commentary: “She does indeed love the protagonist, but she is not in love with him, as he at first believed.” She has a great affection for him as indicated by the Italian word Dante uses to describe her here: innamorata. If we consider the Psalm verse she sang we can understand that her love is a reflection of the love and mercy of God who forgives Dante’s sins.

Following her step for step as she moves upstream, Dante’s imagination turns Matelda into a nymph at play in the forest speckled with sunlight. Earlier, recall, he envisioned her as another Proserpine. She is definitely a resource for the workings of his po etic imagination, which continues the theme of the poets of the Golden Age noted toward the end of the previous canto.

5. After a short walk along the banks of the Lethe (Matelda on her side and Dante, Virgil, and Statius on the opposite side) the stream curves and the group find themselves facing east and the still-rising sun. The east is an ancient Christian symbol for the r ising of Christ, and in countless churches, the altar toward which we pray, is at the east end.

Keeping this symbolism in mind, Matelda’s words carry a heightened sense of expectation as she stops and tells Dante (“my brother”) to look and listen. At this moment, as some commentators suggest, Matelda raises the curtain on a drama of profound proportio ns, and nothing will be the same after this.

6. In spite of the fact that he’s been told there is no “weather” above the Gate below, Dante mistakes this burst of light for lightning until he realizes that its light is still there–-and increasing in brightness. Added to this mysterious light is beautiful (“heavenly”) music, which causes him to vent his anger at Eve who, by her sin, lost the whole of this heavenly place for the rest of humankind, including himself.

7. Dante is moving along the stream again, enchanted by the brilliant light which seems to have caught the air on fire, and the singing which has turned into a chant. Straining to comprehend what he sees and hears, and yearning for even more, he invokes the Mu ses to come to his aid by enabling him to write it all down. This holy invocation was common among the ancients who sought the Muses’ inspiration. Recall that Dante invoked Caliope, the chief of the Muses and Muse of epic poetry, in the first canto of the P urgatorio. Now he invokes Urania, the muse of astronomy and all things celestial–-another foretaste of what is to come. The Poem he writes (and which we read) will be their reward to him for his perseverance. His asking the Muses to “let the streams of Heli con burst forth” is a reference to their home on the mountain sacred to Apollo (god of poetry). On this mountain there were two fountains, Aganippe and Hippocrene, sacred to the Muses. This invocation of the pagan deities is also a way of bringing both the sacred and the profane into the ceremonial action of the great drama that is about to take place. Note how Dante is slowly building the tension and suspense that will soon be released.

8. The great mystical pageant now begins. It is an allegory of the Church Triumphant, a theological term referring to all the Saints and all who have died and are in heaven. Up to this point in the Poem there hasn’t been anything like this but, as the reader w ill see, it fits perfectly here as Dante moves from the level of reason to revelation. Only on this level will he understand the meaning of his experiences here at the top of the Mountain and as they lead him into Paradise.

At the head of the great procession Dante sees what he thinks are seven golden trees. Given the mystical environment of the Earthly Paradise this sight doesn’t seem too out of the ordinary to him, and he probably connects them to the flash of light and the heavenly singing. However, as he keeps walking along the bank of the Lethe, he gets closer to the “trees” and realizes that they are immense candlesticks–a minor example of moving from reason to revelation.

In English, though this is a mistake, we tend to think of candles and candlesticks as synonymous. A candlestick is basically a candle holder. A candle sits atop a candlestick, and a candelabra is a device that holds several candlesticks. The Italian word Da nte uses here is candelabri. This is sometimes translated as candlesticks. So, what Dante most likely saw from a distance were seven gold trees and their branches. Closer up he realized these were seven huge candelabra. But, it’s not clear in the text at th is point how many candles these candelabra held.

Now from the singing he makes out the word “Hosanna,” in Hebrew a plea meaning “save us!” In the Christian tradition, the word is used in the ritual of the Mass as an acclamation of praise just before the consecration of the bread and the wine. It recalls t he joyful shouts of the crowds when Jesus came into Jerusalem shortly before he was killed. St. Matthew quotes this acclamation in his Gospel (21:9): “Hosanna to the son of David! Blessed is he that comes in the name of the Lord.”Note how this single word h ere imparts both a scriptural and a liturgical significance to what is about to happen.

9. As Dante continues to observe the candelabra the light above them fills the dark forest more than a full moon on a clear night. It would seem that each candlestick on these candelabra has a light at the top (but we’re not told it is a lighted candle). Altho ugh there might be several candelabra and candlesticks with lights, Dante uses the word arnese to describe it–in other words a kind of “device.” One suspects that the lack of specificity here is intended to focus our attention on the supernatural glory of t he scene rather than the various stage props. We’re intended to see the candelabra-–as Dante sees them–-as an ensemble making up a single unit. And as he has done at other amazing experiences, he turns around, awestruck, to see Virgil’s reaction to this rev elatory manifestation. For once, Virgil, who represents human Reason as far as it can go, appears to be more amazed than Dante. Recall that when he consecrated and crowned Dante earlier, Virgil told him that he had reached the limits of Reason. Perhaps “mys tified” is a better word to describe his reaction here because he has not been initiated into the Christian faith as Dante has, and doesn’t “see” this revelation as his pupil does.

10. Though Matelda, reminiscent of Virgil, chides him here, it will become clear that Dante intends to focus on one part of the mystical pageant at a time. This way both he and his readers have time to enrich themselves on the meaning of what they see until the whole procession is on stage across the stream and right in front of him/us. At this point, he is facing east with the stream to his left, which acts as a kind of mirror for the action on the other side. In this “mirror” he also sees his left side. And soon enough, as he tells us, he stopped in order to take in the whole scene. Now, there gradually comes into view a group of people dressed in dazzlingly white garments. That they walk slowly, like modest brides, adds to the ceremonial nature of the proces sion. More importantly, a nuptial theme is introduced here which brings with it sub-themes of love, purity, joy, union, and the joining of things heavenly and earthly in this forest cathedral.

11. The number seven has a long history and significance in the Judeo-Christian tradition, indicating fullness, completion, and perfection. One can trace this back to the seven days in the first chapter of the Book of Genesis. Other uses of this number are foun d throughout the Hebrew Bible. In the New Testament two notable examples can be found: one in the Gospel of St. John, and a great many in the Book of Revelation, both said to have been written by the same author. Seven times in St. John’s Gospel, Jesus uses the phrase, “I AM,” a self-reference to the divinity, first used when God identified himself to Moses in the Book of Exodus (3:14). Jesus tells his hearers: I AM the bread of life, I AM the light of the world, I AM the door, I AM the good shepherd, I AM th e resurrection and the life; I AM the way, the truth, and the life, and I AM the vine. In Revelation 4:5 we read: “Seven flaming torches burned in front of the throne, which are the seven spirits of God.” Traditionally, these seven spirits of God have been understood as the seven Gifts of the Holy Spirit: wisdom, understanding, counsel, might, knowledge, piety, and respect for the Lord. Note also that the rainbow has seven colors. The Poet probably borrows from the prophet Ezekiel (1:28) who like the author o f the Book of Revelation, has a vision of God enthroned in heaven: “Just like the appearance of the rainbow in the clouds on a rainy day so was the appearance of brilliance that surrounded him. Such was the appearance of the likeness of the glory of the Lord.”

12. As the stately procession moves slowly past Dante, we learn that the people dressed in white (symbolizing the illumination of faith) following the candlesticks are twenty-four elders crowned with flowers. This image is directly from the Book of Revelation ( 4:4): “Surrounding the throne I saw twenty-four other thrones on which twenty-four elders sat, dressed in white garments and with gold crowns on their heads.” Note how Dante likens himself to St. John who records his heavenly vision in this last book of the New Testament.

These twenty-four white-robed elders, crowned with flowers, represent the books of the Hebrew Bible and Old Testament. The fleur de lis is not actually a lily but a yellow iris. It often appears in a stylized form on emblems and banners, particularly in France. Here in the poem the flower is probably white, and it symbolizes faith.

Over the centuries and to this day there have been various lists of the books of the Hebrew Bible and Old Testament. Dante used the list created in 391 AD by St. Jerome in his Prologus Galaetus, the introduction to his Latin translation of the Book of Kings (which, in his time, included 1 & 2 Kings and 1 & 2 Samuel). In his Prologus St. Jerome lists 24 books in three groupings: The Law included five books (Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers, and Deuteronomy). The Prophets included eight books (Joshua, Judges , 1-2 Samuel, 1-2 Kings, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, and the twelve Minor Prophets as one book). The Writings included eleven books (Job, Psalms, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Song of Songs, Daniel, 1-2 Chronicles, Ezra/Nehemiah, Esther, Ruth, and Lamentations. To gether these Books of the Hebrew Bible symbolize all revelation before Christ.

13. The Poet mentions that these winged creatures were crowned with green leaves (symbolizing hope). Recall that the elders were crowned with white flowers (symbolizing faith). And, moving ahead, we will see that the figures at the end of the procession are cro wned with red flowers (symbolizing love).

Faced with an embarrassment of riches, as it were, Dante must choose his description of the four winged creatures from classical mythology or from Scripture.

Each of the four creatures has six wings that are covered with eyes-–a symbol of omniscience. Focusing on the eyes for a moment, Dante tells us that they remind him of Argus, the giant with a hundred eyes who guarded Io in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (I:622ff). More to the point, however, he sends us to the prophecy of Ezekiel (1:4f) who has a vision in which he sees four living creatures, each with four wings and four heads (but no mention of eyes). Then he tells us that his creatures across the stream resemble E zekiel’s except for the wings. These resemble those in the vision of St. John in the Book of Revelation (4:6-8): “In the center and around the throne, there were four living creatures covered with eyes in front and in back. The first creature resembled a li on, the second was like a calf, the third had a face like that of a human being, and the fourth looked like an eagle in flight. The four living creatures, each of them with six wings, were covered with eyes inside and out.”

14. Argos Panoptes is a many-eyed giant in Greek mythology. Known for his perpetual vigilance, he served the goddess Hera as a watchman. His most famous task was guarding Io, a priestess of Hera, whom Zeus had transformed into a heifer. Argus's constant watch, with some of his eyes always open, made him a formidable guardian. His eventual slaying by Hermes, on Zeus's orders, is a prominent episode in the myths surrounding him, and his eyes were then incorporated into the peacock's tail by Hera in his honor.

15. Both Ezekiel and Isaiah will identify these creatures as seraphim, the highest order of the angels. In the Christian tradition, the creatures from the Book of Revelation represent the four Evangelists (lion=St. Mark, calf=St. Luke, human=St. Matthew, eagle= St. John). Together, they represent what is noblest, strongest, wisest, and swiftest in creation.

16. Dante’s attention is drawn first to the griffin. This is a mythical creature that has the head and neck of a great eagle and the body of a lion. This griffin is special because it also has wings, wings that rise so high they pierce the veil of light over th e forest and beyond on either side of the central streamer of colored light. All the eagle parts of the griffin are gold, while the lion parts are white with red spots.

As for the chariot, not only is it more beautiful than those driven by Scipio Africanus or the Emperor Augustus in their Roman triumphs. In fact, it is more gorgeous than the mythical chariot of the sun! (By the way, it is not clear which Scipio Africanus D ante is referring to here. The Elder (235-183 BC) was famed for his defeat of Hannibal, and the Younger (185-129 BC) was famed for his defeat of Carthage.)

17. That the griffin’s wings seem to pierce the heavens is another image of the union of the divine and the earthly in this Earthly Paradise–the only place where this pageant can take place.

And there is much symbolism to see in what Dante sees. As we saw, the four creatures with six wings covered with eyes represent the four Evangelists who wrote the New Testament Gospels. The eyes represent not only omniscience, but also the movement of the W ord of God throughout the world, when both sees and is seen. It will soon become evident that the chariot represents the Church Triumphant (all those in Paradise). The wheels of the chariot represent the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament. And, most importa ntly, the griffin represents Christ in his two natures as God and human.

18. These three ladies dancing alongside the right wheel of the chariot represent the three Theological Virtues of Faith, Hope, and Love. They are traditionally associated with the colors white (Faith), green (Hope), and red (Love). Because Love is the grea test of the virtues (see I Cor. 13:13), it is she whose song leads the tempo of the dance. What Dante sees here is not simply three ladies clothed in different colors. Their actual bodies and their clothes are all of one color.

Note that hope moves at the direction of Faith and Love. St. Thomas Aquinas is even more specific, stating that Faith precedes Hope:

“Absolutely speaking, faith precedes hope. For the object of hope is a future good, arduous but possible to obtain. In order, therefore, that we may hope, it is necessary for the object of hope to be proposed to us as possible. Now the object of hope is, in one way, eternal happiness, and in another way, the Divine assistance: and both of these are proposed to us by faith, whereby we come to know that we are able to obtain eternal life, and that for this purpose the Divine assistance is ready for us, accor ding to Hebrews 11:6: ‘He that cometh to God, must believe that He is, and is a rewarder to them that seek Him.’ Therefore it is evident that faith precedes hope” (Summa Theologiae II-II, q. 17, a. 7).

19. Along the left side of the chariot Dante sees four dancing ladies dressed in purple, led by one with three eyes. These ladies represent the Cardinal Virtues of Prudence, Justice, Fortitude, and Temperance. They are led by Prudence with the third eye which enables her to see the past, present, and future. In his Convivio, Dante writes: “One should therefore be prudent, that is, wise, and to be wise requires a vivid memory of things past, a sound knowledge of things present, and a clear foresight for th ings future” (IV, xxvii). Their gowns of imperial purple set them apart as the Classical Virtues, and since the color purple consists mostly of red, they are also grounded in love. Quoting the famous 15th century commentator, Mark Musa notes: “Christofo ro Landino states: ‘Dante presents these women dressed in purple to denote charity and the fervor of love, without which no one can have these virtues.’” These two sets of virtues (Cardinal and Theological) stand on either side of the chariot (the Church Tr iumphant) signifying how they work together in communion with the Church for the development of the soul.

20. Following the chariot, and comprising the last part of the mystic procession, Dante sees seven more elders, serious in composure, and dressed in the white garments of faith and crowned with red flowers, again symbolizing great love. These seven elders a re given symbolic descriptions. (a) The first elder, the disciple of Hippocrates, is St. Luke, author of the Acts of the Apostles and called by St. Paul “the beloved physician.” (b) The second elder, carrying the fearsome sword (symbol of the word of God), is St. Paul. He represents the fourteen Letters attributed to him (Romans, 1 Corinthians, 2 Corinthians, Galatians, Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians, 1 Thessalonians, 2 Thessalonians, 1 Timothy, 2 Timothy, Titus, Philemon, and Hebrews). (c,d,e,f) Followin g these two are four more. They represent the Letter of St. James, the two Letters of St. Peter, the three Letters of St. John, and the Letter of St. Jude. (g) The last elder and the final figure in the procession is depicted as an old man with a radiant fa ce, walking as if in a dream. This is St. John the Evangelist, author of the Book of Revelation, the last book in the New Testament which is filled with his visions and dreams. Dante certainly identifies with him and his visions in this canto, and in art, S t. John is often depicted asleep.

21. In summary, there are 9 sections to the Mystical Pageant, 43 characters, and 3 props:

Section 1: The great gold candlesticks (prop 1). These represent the sevenfold Spirit of God symbolized in the Gifts of the Holy Spirit in the streamers of colored light: Wisdom, Understanding, Counsel, Fortitude, Knowledge, Piety, Reverence for God.

Section 2: The 24 elders representing the books of the Hebrew Bible. They are crowned with white flowers symbolizing Faith.

Section 3: The 4 Evangelists/Gospels represented by the 4 creatures with 6 wings covered with eyes symbols of omniscience. They are crowned with green leaves symbolizing Hope. The lion is St. Mark, the calf is St. Luke, the human is St. Matthew, the eag le is St. John). Together, they represent what is noblest, strongest, wisest, and swiftest in creation.

Section 4: The Griffin pulling the chariot (prop 2). This section is the centerpiece of the entire pageant. He represents the dual nature of Christ as God and human. He has wings which reach up through and beyond the canopy of streaming light from the s even candlesticks. This is a symbol of Christ’s triumph. His eagle part is pure gold (immortality), and the lion part is white with red spots (the Body and Blood of the Eucharist). The red spots can also symbolize the wounds of his torture and crucifixion. The chariot represents the Church Triumphant (everyone in Heaven).

Section 5: The 3 Theological Virtues near the right wheel of the chariot as three dancing ladies in white (Faith), green (Hope), and red (Love).

Section 6: The 4 Cardinal Virtues near the left wheel of the chariot as four dancing ladies in royal purple, symbolizing Prudence, Justice, Fortitude, and Temperance.

Section 7: The Book of Acts (St. Luke) and the Letters of St. Paul, crowned with red flowers symbolizing love. (Sword–prop 3).

Section 8: The 4 authors of the lesser Epistles (Sts. James, Peter, John, Jude), also crowned with red flowers symbolizing Love.

Section 9: The Book of Revelation (St. John), also crowned with red flowers.

Top of page