Dante's Divine Comedy: Purgatorio

Canto XVI

As the poets stumble through the blinding, suffocating smoke, Virgil bears the voices of the penitent Wrathful singing their prayer, the Agnus Dei (the Lamb of God). Their punishment is apt because anger blinds judgment and suffocates all feeling. The spirit of Marco the Lombard guides the poets through the cloud as be outlines the political factors corrupting the world, plays down the influences of fate on human affairs, affirms the divine notion of free will and laments the lack of good political and religious leaders. The smoke thins out with the approach of the third angel.

Darkness of hell, and of a night deprived

Of every planet under a poor sky,

As much as may be tenebrous with cloud,[1]

Ne'er made unto my sight so thick a veil,

As did that smoke which there enveloped us,

Nor to the feeling of so rough a texture;

For not an eye it suffered to stay open;

Whereat mine escort, faithful and sagacious,

Drew near to me and offered me his shoulder.

E'en as a blind man goes behind his guide,

Lest he should wander, or should strike against

Aught that may harm or peradventure kill him,

So went I through the bitter and foul air,

Listening unto my Leader, who said only,

"Look that from me thou be not separated."

Voices I heard, and every one appeared

To supplicate for peace and misericord

The Lamb of God who takes away our sins.[2]

Still "Agnus Dei" their exordium was;

One word there was in all, and meter one,

So that all harmony appeared among them.

"Master," I said, "are spirits those I hear?"

And he to me: "Thou apprehendest truly,

And they the knot of anger go unloosing."

"Now who art thou, that cleavest through our smoke

And art discoursing of us even as though

Thou didst by calends still divide the time?"[3]

After this manner by a voice was spoken;

Whereon my Master said: "Do thou reply,

And ask if on this side the way go upward."

And I: "O creature that dost cleanse thyself

To return beautiful to Him who made thee,

Thou shalt hear marvels if thou follow me."

"Thee will I follow far as is allowed me,"

He answered; "and if smoke prevent our seeing,

Hearing shall keep us joined instead thereof."

Thereon began I: "With that swathing band

Which death unwindeth am I going upward,

And hither came I through the infernal anguish.

And if God in his grace has me infolded,

So that he wills that I behold his court

By method wholly out of modern usage,

Conceal not from me who ere death thou wast,

But tell it me, and tell me if I go

Right for the pass, and be thy words our escort."

"Lombard was I, and I was Marco called;

The world I knew, and loved that excellence,

At which has each one now unbent his bow.[4]

For mounting upward, thou art going right."

Thus he made answer, and subjoined: "I pray thee

To pray for me when thou shalt be above."

And I to him: "My faith I pledge to thee

To do what thou dost ask me; but am bursting

Inly with doubt, unless I rid me of it.

First it was simple, and is now made double

By thy opinion, which makes certain to me,

Here and elsewhere, that which I couple with it.

The world forsooth is utterly deserted

By every virtue, as thou tellest me,

And with iniquity is big and covered;

But I beseech thee point me out the cause,

That I may see it, and to others show it;

For one in the heavens, and here below one puts it."

A sigh profound, that grief forced into Ai!

He first sent forth, and then began he: "Brother,

The world is blind, and sooth thou comest from it!

Ye who are living every cause refer

Still upward to the heavens, as if all things

They of necessity moved with themselves.

If this were so, in you would be destroyed

Free will, nor any justice would there be

In having joy for good, or grief for evil.

The heavens your movements do initiate,

I say not all; but granting that I say it,

Light has been given you for good and evil,[5]

And free volition; which, if some fatigue

In the first battles with the heavens it suffers,

Afterwards conquers all, if well 'tis nurtured.

To greater force and to a better nature,

Though free, ye subject are, and that creates

The mind in you the heavens have not in charge.

Hence, if the present world doth go astray,

In you the cause is, be it sought in you;

And I therein will now be thy true spy.

Forth from the hand of Him, who fondles it

Before it is, like to a little girl

Weeping and laughing in her childish sport,[6]

Issues the simple soul, that nothing knows,

Save that, proceeding from a joyous Maker,

Gladly it turns to that which gives it pleasure.

Of trivial good at first it tastes the savor;

Is cheated by it, and runs after it,

If guide or rein turn not aside its love.

Hence it behooved laws for a rein to place,

Behooved a king to have, who at the least

Of the true city should discern the tower.

The laws exist, but who sets hand to them?

No one; because the shepherd who precedes

Can ruminate, but cleaveth not the hoof;

Wherefore the people that perceives its guide

Strike only at the good for which it hankers,

Feeds upon that, and farther seeketh not.

Clearly canst thou perceive that evil guidance

The cause is that has made the world depraved,

And not that nature is corrupt in you.

Rome, that reformed the world, accustomed was

Two suns to have, which one road and the other,

Of God and of the world, made manifest.[7]

One has the other quenched, and to the crosier

The sword is joined, and ill beseemeth it

That by main force one with the other go,[8]

Because, being joined, one feareth not the other;

If thou believe not, think upon the grain,

For by its seed each herb is recognized.

In the land laved by Po and Adige,

Valor and courtesy used to be found,

Before that Frederick had his controversy;[9]

Now in security can pass that way

Whoever will abstain, through sense of shame,

From speaking with the good, or drawing near them.

True, three old men are left, in whom upbraids

The ancient age the new, and late they deem it

That God restore them to the better life:

Currado da Palazzo, and good Gherardo,

And Guido da Castel, who better named is,

In fashion of the French, the simple Lombard:[10]

Say thou henceforward that the Church of Rome,

Confounding in itself two governments,

Falls in the mire, and soils itself and burden."

"O Marco mine," I said, "thou reasonest well;

And now discern I why the sons of Levi

Have been excluded from the heritage.[11]

But what Gherardo is it, who, as sample

Of a lost race, thou sayest has remained

In reprobation of the barbarous age?"[12]

"Either thy speech deceives me, or it tempts me,"

He answered me; "for speaking Tuscan to me,

It seems of good Gherardo naught thou knowest.

By other surname do I know him not,

Unless I take it from his daughter Gaia.

May God be with you, for I come no farther.

Behold the dawn, that through the smoke rays out,

Already whitening; and I must depart—

Yonder the Angel is—ere he appear."

Thus did he speak, and would no farther hear me.

Illustrations of Purgatorio

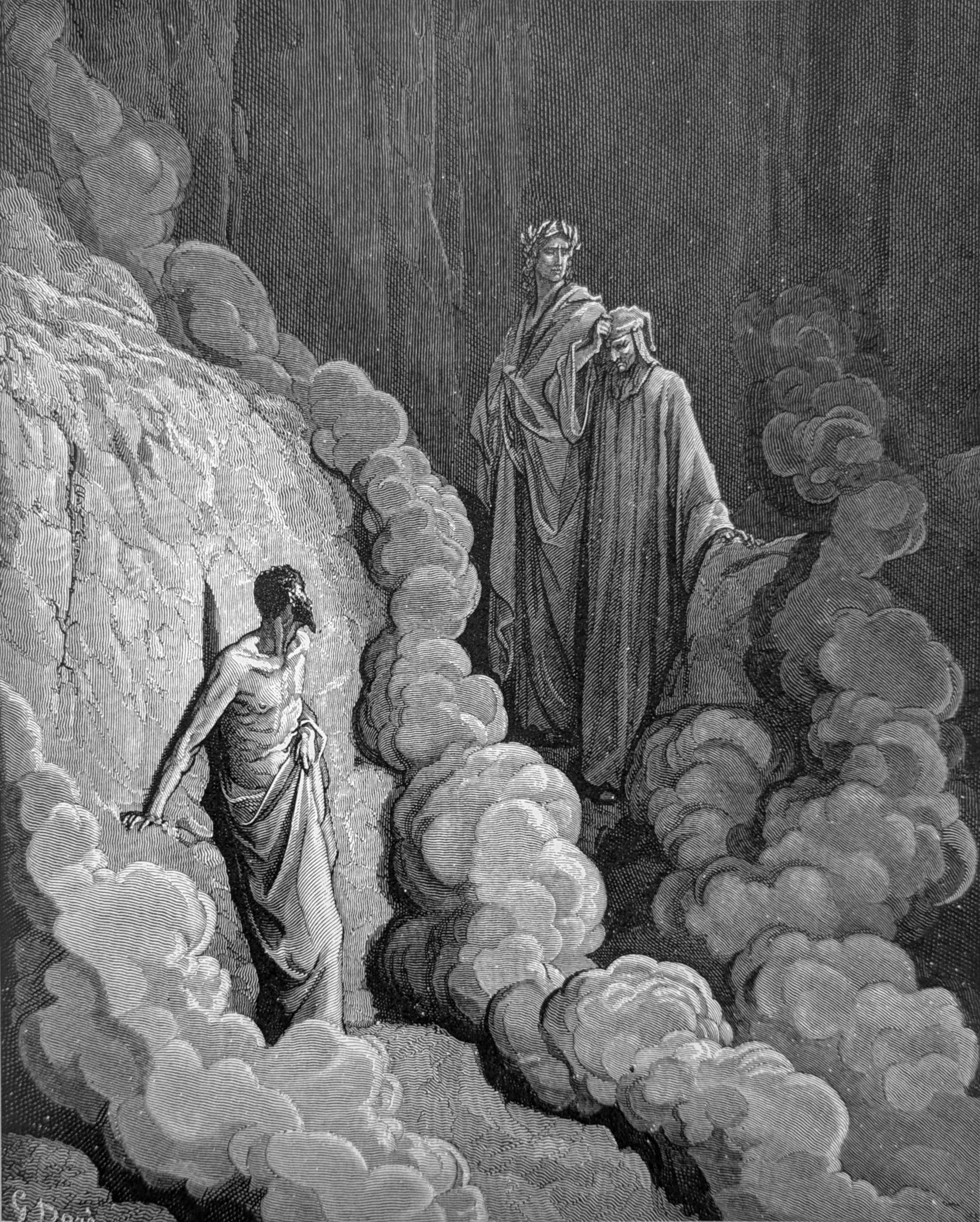

"Now who art thou, that cleavest through our smoke / And art discoursing of us even as though / Thou didst by calends still divide the time?" Purg. XVI, lines 25-27

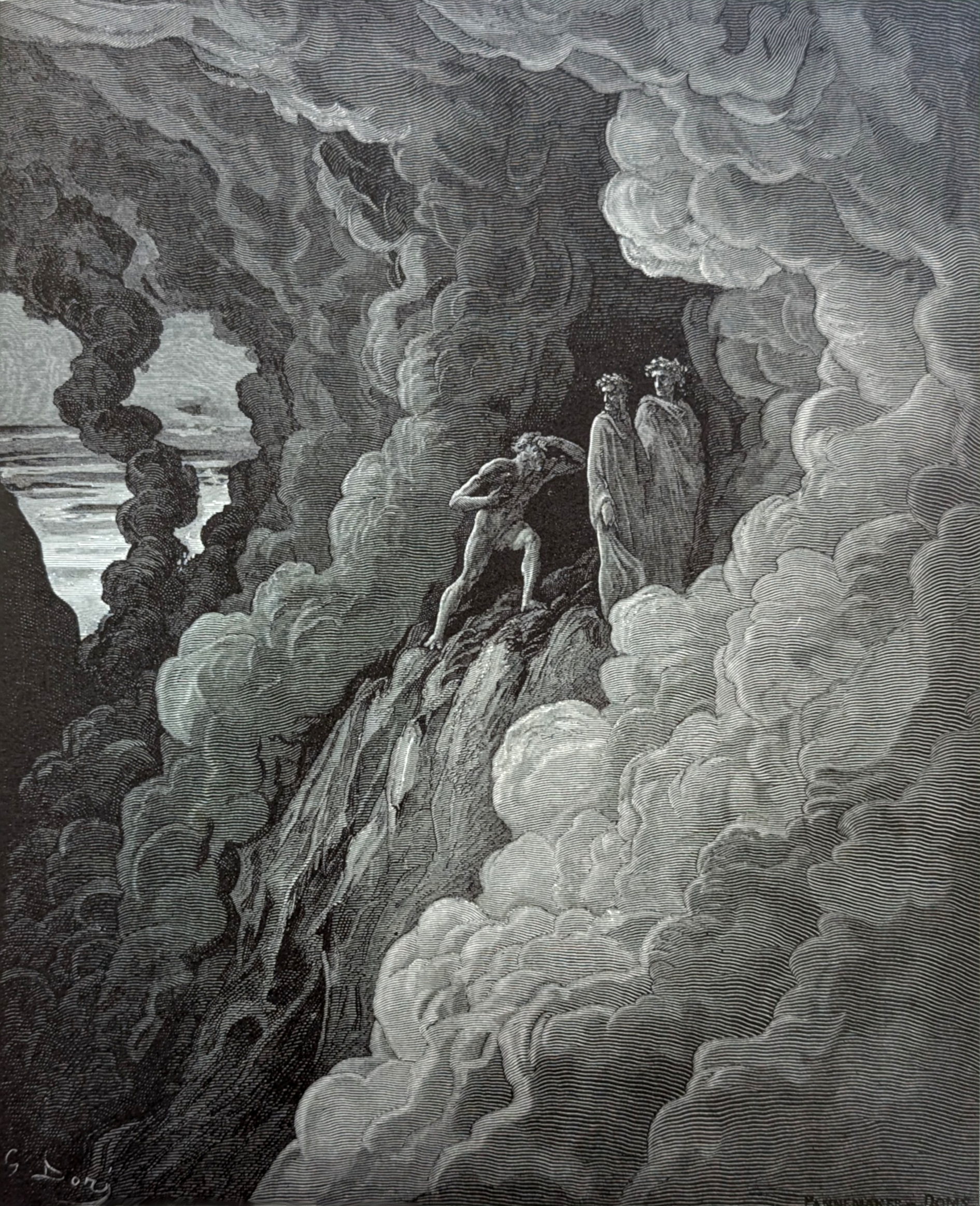

"Thee will I follow far as is allowed me," / He answered; "and if smoke prevent our seeing, / Hearing shall keep us joined instead thereof." Purg. XVI, lines 34-36

Footnotes

1. Tenebrous, Latin, tenebrōsus, tenebrae, “darkness, shadows”.

2. The particular prayer the sinners are reciting is an ancient one from the liturgy of the Mass which the congregation recites after the Our Father and before they receive Holy Communion: “Lamb of God (Agnus Dei), you take away the sins of the world, have mercy on us. Lamb of God, you take away the sins of the world, have mercy on us. Lamb of God, you take away the sins of the world, grant us peace.” The Lamb of God is a reference to Christ as the sacrificial victim who died to take away our sins and grant us peace. The innocent and spotless sacrificial lamb contrasts here with the sin of anger. Christian iconography often depicts a lamb as representing Christ. The significance of this prayer is also heightened because it comes from the liturgy of the Mass which, for Christians, is the highest form of prayer. All through the Purgatorio we are intended by Dante to see elements and symbols of the liturgy in which the penitent souls participate as they purged from their sins in sure anticipation of the heaven that awaits them.

3. In the Italian, the soul not only points out that Dante is alive, but that he (the living) measures time by calendars (or calends). It’s a subtle point the soul makes, but the Poet reminds us by doing this that space and time in Purgatory are radically different from what the living experience on earth. Note also that Virgil doesn’t answer for Dante, but he does tell him what to ask.

4. Marco first identifies himself as a Lombard. Lombardy is presently one of the provinces of north central Italy, its chief cities being Milan, Brescia, and Bergamo. In Dante’s time, being a Lombard or from Lombardy often meant northern Italy generally. We do know that he also lived in Venice, that he was noted for his many noble qualities, and that, while he knew the ways of the world, he lived a generally virtuous life. Benvenuto da Imola writes that “He was a certain noble knight of the illustrious city of t he Venetians.” According to some of the oldest commentators, including Benvenuto, his several princely acquaintances indicate that he may at times have been a political counselor and diplomat. Ronald Martinez connects him with a major character we met at the end of the Inferno: Count Ugolino in Canto 33. Marco denounced him for his betrayal of the Guelphs. Hollander suggests he may have been well-known enough in Dante’s time that additional biographical information was unnecessary.

That Marco was apparently a man who strove to live a virtuous life–-noting that not many do-–is manifest in his answer to one of Dante’s questions: “The path you’re on now is, in fact, the one that will lead you upward.” And at this point he seems to recognize the deeper significance of Dante’s gifted journey by asking the Pilgrim to pray for him when he reaches Paradise. By the way, he is the first soul we’ve met in Purgatory who has asked him to do this. Dante obviously takes the measure of Marco, because w hat he already knows of him from real life and what he says here enables the Pilgrim to raise a question we will soon discover is of great importance to both men, particularly because both of them realize the social consequences of lives lived without virtue.

5. That the stars and planets have an influence on the human character and human affairs is an ancient astrological principle that was still very much alive in Dante’s time. He himself believed that the stars had some minor role in the direction of human affairs, yet he also placed astrologers and fortune-tellers in Canto 20 of the Inferno, walking forward with their heads twisted backwards! Yet even today various forms of astrology are popular.

Fundamentally, that the stars have a more than passing influence on human behavior is a denial of free will. In Paradiso 5:19-24, Beatrice, referring to free will, tells Dante: “The greatest gift that our bounteous Lord bestowed as the Creator, in creating, the gift He cherishes the most, the one most like Himself, was freedom of the will. All creatures with intelligence, and they alone, were so endowed both then and now.” Quite an amazing statement! If one denies the freedom of the will, they are no better than animals. These, in fact, are the ones Virgil refers to when he and Dante enter the gate of Hell in Canto 3 (l.18) of the Inferno: “…souls who lost the good of the intellect.” By choosing sin over grace and virtue, the souls have forfeited their free w ill. Better yet, they’ve misused their free will to choose sin over God. In Canto 14 above, Guido del Duco told Dante that the banks of the Arno are populated by people who have become like animals-–corrupted their wills and chosen evil over good.

If, as Marco suggests, human affairs were guided by the stars–-fate, in other words, not only would we have no free will, but this raises significant questions about the nature and workings of justice, good and evil, and the rewards or punishments that foll ow from them. No wonder he sighs! But he sighs also at human moral blindness, perhaps Dante’s included. There is an irony here, of course, because though both Dante and Marco are blinded by the thick smoke of this place, Marco can perceive what Dante wants to see but can’t until Marco answers his question. In the largest sense possible, Purgatory is a correction of faulty sight.

6. When we are born, Marco explains, our souls are as child-like as our baby bodies. Having watched small children at play, we can follow the image he uses: they are distracted by one pretty thing or another, and want whatever strikes their fancy at the moment . No doubt, these pretty things are good. But, innocent as they are, children need to be guided and taught to control their impulses. And, sadly, there’s a bite to what he says next: grown-ups are not much different from children in this regard. They also need virtuous guides and leaders if they are to follow the path toward the “Heavenly City.”

“Ah!,” Dante replies, “There are laws, there are guides.” And Marco agrees. But, he argues, no one enforces those laws and, we might be persuaded to say, (almost) no one keeps them. What follows is already clear from Dante’s own life and experience: the Emperor has not lived up to his responsibilities, and the Pope, who should be the leader of the faithful par excellence, is himself corrupt and lawless (behaving, at times, as though he were the Emperor). His example is worthless, and his greed is an evil incentive for others to follow. We ask with chagrin: if the following of Christ is the standard by which Christians should live, shouldn’t the Pope lead the way?

Another perspective from St. Thomas (Summa Theol. I, q. u5, a. 4, ad 3): “The majority of men follow their passions, which are movements of the sensitive appetite, in which movements heavenly bodies can cooperate: but few are wise enough to resist these passions. Consequently astrologers are able to foretell the truth in the majority of cases, especially in a general way. But not in particular cases; for nothing prevents man’s resisting his passions by his free will.”

In the end, Marco answers Dante’s question: the cause of the poor state of affairs in the world is not our inner nature (though even that is in danger of corruption). No, it’s bad leadership.

7. Marco looks back to an ideal time when Rome’s “two suns”–-the Emperor and the Pope, lived in peace, each upholding their own responsibilities and each respecting the rights of the other. Unfortunately, as he noted already, the Pope has usurped what rightly belonged to the Emperor and, symbolically, the sword of the empire has melded with the shepherd’s crook of the papacy. The harmony between these two ruling entitles has been lost and, it seems, neither one cares. Dorothy Sayers, in her commentary here, note s that Dante is probably thinking here of the “great days of the Byzantine Empire, particularly, perhaps, under Justinian.” And, she adds, “The empire envisaged by Dante in his political writings is not the Holy Roman Empire of Western feudalism, nor is it the pagan empire of Augustus or Trajan.”

At Dante’s time, the Pope lived in and ruled from Rome, but the Emperor virtually never traveled south of the Alps, one of the causes of the civil strife between Guelphs and Ghibellines that ripped viciously through the social fabric of northern Italy. Dante's exile is a direct result of this strife. And, of course, the papacy’s fraudulent claim that the empire was subject to it only made matters worse. Dante will come back to this theme in subsequent parts of the Poem.

At the same time, Marco’s noting of Rome’s “two suns” is actually Dante’s idea (and ideal), which he set out in De Monarchia (3.11.7-10; see this quote at the end of this canto’s commentary). Musa tells us here that “Dante objected to the idea that the empire could receive no light of its own but only that reflected by the papacy. Hence, he devised the unusual concept of “two suns,” while most of his contemporaries used the image of the sun and the moon, the sun being the Pope and the moon being the Emperor.

8. Crozier, from Latin, crux, “cross”, meaning the staff used by the pope.

9. Using the names of two different rivers, Marco echoes Guido’s image in Canto 14 of the banks of the Arno populated and contaminated by equally “disreputable” people. As it happened, Marco himself was from the regions of the Po and the Adige. That he mention s Frederick II is fascinating, because Dante put him in Hell with the heretics in Canto 12 of the Inferno. But, as Hollander remarks, “For Dante, Frederick was the last emperor to take his role as emperor of all Europe seriously.” Even though he fomented continual strife between papacy and empire.

In light of this, Musa notes: “Emperor Frederick II, last of the emperors from Dante’s point of view, was involved in successive conflicts with the papacy: he met resistance from Popes Honorius III, Gregory IX, and Innocent IV. Before he was forced into constant conflict with the Church, he was renowned for the high culture he brought to Italy. The ideals of chivalry peaked during his reign and began their decline with this discord.”

10. Again, echoing Guido del Duca in Canto 14, Marco makes note of noble characters whose virtue contrasts with the present state of affairs. Currado da Palazzo was a Guelph nobleman from Brescia. He represented Charles of Anjou in Florence, and was Podestà of both Florence and then Piacenza. His bravery and courage are noted by Benvenuto da Imola, who wrote that in a certain battle Currado was the standard bearer. In an attempt to confuse his troops, an enemy soldier is said to have hacked off both his hands so he would drop the flag. Currado, however, continued to lead his soldiers forward, embracing the flag with both arms. Gherardo da Camino was a nobleman, a supporter of the White Guelphs, and captain-general of Treviso for more than 20 years. He was apparently generous and hospitable to poets, including Dante when he was in exile. Guido da Castel was yet another unassuming, but generous and hospitable, nobleman from Reggio Emilia who also honored Dante with his generosity and hospitality. Note how all three men are examples of nobility and virtue in contrast to the corruption that Marco points out.

11. We are accustomed to Dante’s tangling one or more items together along the way of his Poem. On the one hand, this is a simple “Thank you!” for the breadth, length, and depth of Marco’s explanation throughout this canto. But what, we might ask, does this have to do with the biblical rules governing the Levites? It becomes clear enough when we explore a passage in the Book of Numbers (18:20-24):

“Then the Lord said to Aaron: ‘You shall not have any heritage in their land nor hold any portion among them; I will be your portion and your heritage among the Israelites. To the Levites, however, I hereby assign all tithes in Israel as their heritage i n recompense for the labor they perform, the labor pertaining to the tent of meeting … this is a permanent statute for all your generations. But they shall not have any heritage among the Israelites, for I have assigned to the Levites as their heritage the tithes which the Israelites put aside as a contribution to the Lord. That is why I have said, they will not have any heritage among the Israelites.’”

Basically, then, they were forbidden to own property. Instead, they lived off a portion of the offerings brought to the Temple. Dante’s point, of course, is that in amassing great wealth and power, the Church lost its spiritual integrity. Later Church Councils did away with practices that led to such abuses.

12. As noted above, Gherardo da Cammino, was a nobleman from Brescia, captain-general of Treviso, and noted for his generous hospitality to poets. He is known to have entertained Dante during his exile. Marco, of course, thinks Dante is joking not to know who Gherardo was. Yet, ironically, Dante already uses Gherardo’s virtuous life to identify him. Like the other men Marco singled out, Gherardo stands out nobly among a cast of otherwise corrupt characters.

The mention of Gherardo’s daughter, Gaia, seems strange, however, and commentators throughout the centuries have differing opinions to offer about her being mentioned here. Some of the earliest suggest that she was a wanton woman, and that she is mentioned here as another one of Marco’s examples of corruption. Others suggest the opposite, that she was noted for her beauty and virtue. Others, still, claim there is simply not enough evidence to make an accurate judgment.