Dante's Divine Comedy: Purgatorio

Canto III

As Virgil and Dante clamber up the lower slopes of the mountain, the Florentine notices that the rays of the rising sun cast his shadow but pass through Virgil's airy body. With a pang, be remembers that Virgil's spirit is dead and damned. In the First Terrace of Ante-Purgatory, the poets encounter the Excommunicate (including the Emperor Manfred). Although detained by God outside of Purgatory for having been lazy with their faith, these souls endure the delay patiently in the hope of securing divine satisfaction, after which time they will be allowed to ascend the mountain.

Inasmuch as the instantaneous flight

Had scattered them asunder o'er the plain,

Turned to the mountain whither reason spurs us,

I pressed me close unto my faithful comrade,

And how without him had I kept my course?

Who would have led me up along the mountain?

He seemed to me within himself remorseful;

O noble conscience, and without a stain,

How sharp a sting is trivial fault to thee!

After his feet had laid aside the haste

Which mars the dignity of every act,

My mind, that hitherto had been restrained,

Let loose its faculties as if delighted,

And I my sight directed to the hill

That highest tow'rds the heaven uplifts itself.

The sun, that in our rear was flaming red,

Was broken in front of me into the figure

Which had in me the stoppage of its rays;

Unto one side I turned me, with the fear

Of being left alone, when I beheld

Only in front of me the ground obscured.

"Why dost thou still mistrust?" my Comforter

Began to say to me turned wholly round;

"Dost thou not think me with thee, and that I guide thee?

'Tis evening there already where is buried

The body within which I cast a shadow;

'Tis from Brundusium ta'en, and Naples has it.[1]

Now if in front of me no shadow fall,

Marvel not at it more than at the heavens,

Because one ray impedeth not another

To suffer torments, both of cold and heat,

Bodies like this that Power provides, which wills

That how it works be not unveiled to us.

Insane is he who hopeth that our reason

Can traverse the illimitable way,

Which the one Substance in three Persons follows![2]

Mortals, remain contented at the 'Quia;'

For if ye had been able to see all,

No need there were for Mary to give birth;

And ye have seen desiring without fruit,

Those whose desire would have been quieted,

Which evermore is given them for a grief.

I speak of Aristotle and of Plato,

And many others;"--and here bowed his head,

And more he said not, and remained disturbed.

We came meanwhile unto the mountain's foot;

There so precipitate we found the rock,

That nimble legs would there have been in vain.

'Twixt Lerici and Turbia, the most desert,

The most secluded pathway is a stair

Easy and open, if compared with that.[3]

"Who knoweth now upon which hand the hill

Slopes down," my Master said, his footsteps staying,

"So that who goeth without wings may mount?"

And while he held his eyes upon the ground

Examining the nature of the path,

And I was looking up around the rock,

On the left hand appeared to me a throng

Of souls, that moved their feet in our direction,

And did not seem to move, they came so slowly.

"Lift up thine eyes," I to the Master said;

"Behold, on this side, who will give us counsel,

If thou of thine own self can have it not."

Then he looked at me, and with frank expression

Replied: "Let us go there, for they come slowly,

And thou be steadfast in thy hope, sweet son."

Still was that people as far off from us,

After a thousand steps of ours I say,

As a good thrower with his hand would reach,

When they all crowded unto the hard masses

Of the high bank, and motionless stood and close,

As he stands still to look who goes in doubt.

"O happy dead! O spirits elect already!"

Virgilius made beginning, "by that peace

Which I believe is waiting for you all,

Tell us upon what side the mountain slopes,

So that the going up be possible,

For to lose time irks him most who most knows."

As sheep come issuing forth from out the fold

By ones and twos and threes, and the others stand

Timidly, holding down their eyes and nostrils,

And what the foremost does the others do,

Huddling themselves against her, if she stop,

Simple and quiet and the wherefore know not;

So moving to approach us thereupon

I saw the leader of that fortunate flock,

Modest in face and dignified in gait.

As soon as those in the advance saw broken

The light upon the ground at my right side,

So that from me the shadow reached the rock,

They stopped, and backward drew themselves somewhat;

And all the others, who came after them,

Not knowing why nor wherefore, did the same.

"Without your asking, I confess to you

This is a human body which you see,

Whereby the sunshine on the ground is cleft.

Marvel ye not thereat, but be persuaded

That not without a power which comes from Heaven

Doth he endeavor to surmount this wall."

The Master thus; and said those worthy people:

"Return ye then, and enter in before us,"

Making a signal with the back o' the hand

And one of them began: "Whoe'er thou art,

Thus going turn thine eyes, consider well

If e'er thou saw me in the other world."

I turned me tow'rds him, and looked at him closely;

Blond was he, beautiful, and of noble aspect,

But one of his eyebrows had a blow divided.

When with humility I had disclaimed

E'er having seen him, "Now behold!" he said,

And showed me high upon his breast a wound.

Then said he with a smile: "I am Manfredi,

The grandson of the Empress Costanza;

Therefore, when thou returnest, I beseech thee[4]

Go to my daughter beautiful, the mother

Of Sicily's honor and of Aragon's,

And the truth tell her, if aught else be told.[5]

After I had my body lacerated

By these two mortal stabs, I gave myself

Weeping to Him, who willingly doth pardon.

Horrible my iniquities had been;

But Infinite Goodness hath such ample arms,

That it receives whatever turns to it.

Had but Cosenza's pastor, who in chase

Of me was sent by Clement at that time,

In God read understandingly this page,[6]

The bones of my dead body still would be

At the bridge-head, near unto Benevento,

Under the safeguard of the heavy cairn.

Now the rain bathes and moveth them the wind,

Beyond the realm, almost beside the Verde,

Where he transported them with tapers quenched.

By malison of theirs is not so lost

Eternal Love, that it cannot return,

So long as hope has anything of green.

True is it, who in contumacy dies

Of Holy Church, though penitent at last,

Must wait upon the outside this bank[7]

Thirty times told the time that he has been

In his presumption, unless such decree

Shorter by means of righteous prayers become.

See now if thou hast power to make me happy,

By making known unto my good Costanza

How thou hast seen me, and this ban beside,

For those on Earth can much advance us here."

Illustrations of Purgatorio

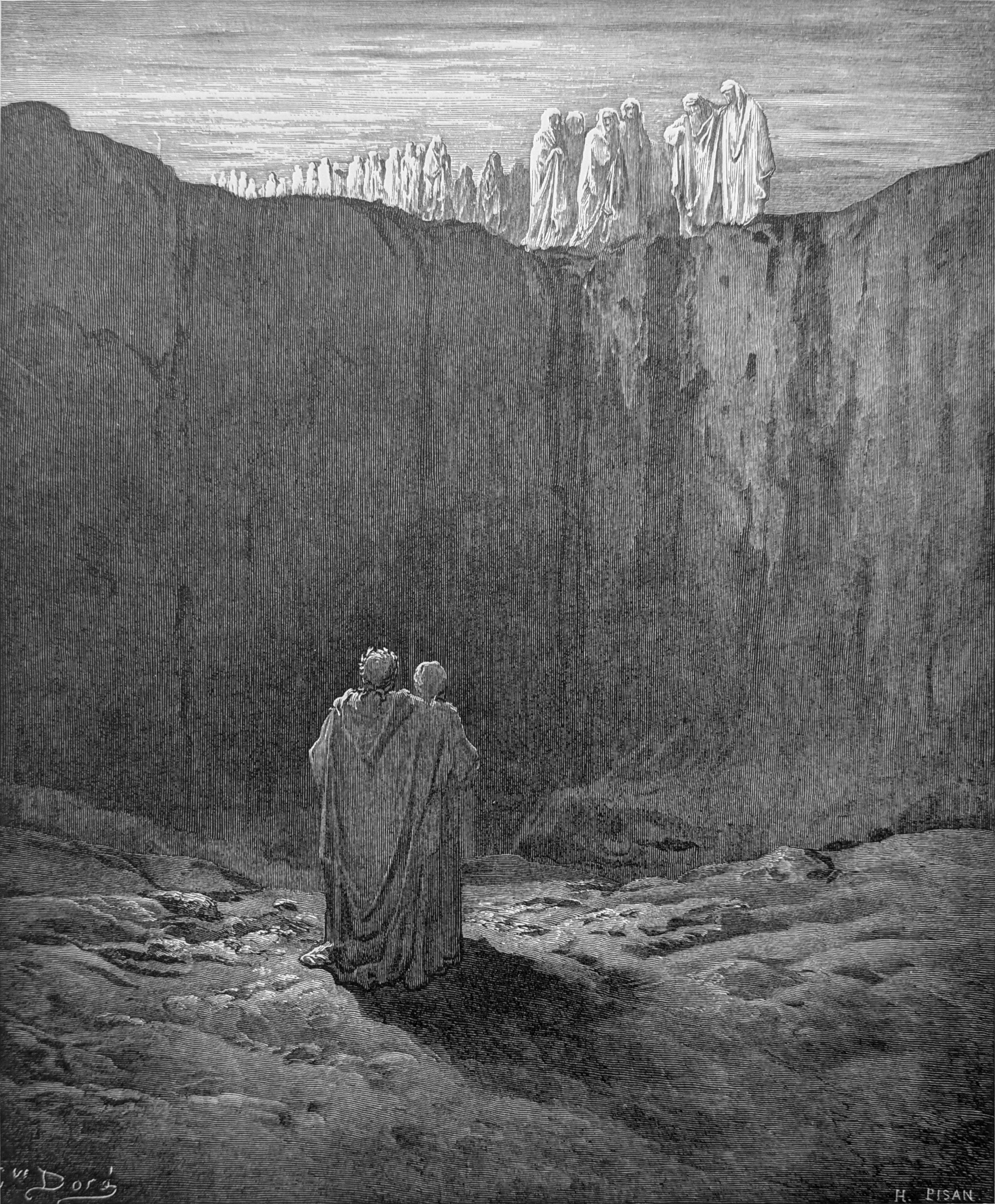

On the left hand appeared to me a throng/ Of souls, that moved their feet in our direction, / And did not seem to move, Purg. III, lines 58-60

Footnotes

1. Dante’s momentary fear of losing Virgil–his “Comfort”–actually prompts Virgil to reassure his companion about his presence, even though he is dead. Though he refers to his own death in Brindisi and reburial in Naples, his point is that, while his spirit-bod y might not cast a shadow, light still passes through him and gives him a kind of corporeal appearance. More than this, though, is his pointing to the cosmos and how light passes unblocked through all the great spheres. While this is another affirmation of Dante’s cosmology, it’s a spiritual affirmation that points to the Light of God which passes unhindered into our souls.

2. He invokes the Trinity.

3. The cities Dante refers to here are at either end of the extremely rugged Ligurian Coast (the Italian Riviera) which stretches from east of Nice in southern France (Turbia), wrapping around Genoa and ends just south of La Spezia (Lerici). It’s a considerable distance between these two cities, and is known for its steep cliffs and daunting mountain passes. As always, the reference to real places enhances the reality of the poem, particularly for those who have experienced them.

4. We have here a handsome, obviously noble soul who bears a mark of violence on his face. He expects that Dante might recognize him; but when he fails to do so, he shows the pilgrim an even larger wound on his chest. While not pushing this identification too far, one is reminded of Jesus’ post-resurrection appearances to his Apostles and how he showed them his wounds. Manfred, as we will see, is hardly a Jesus-figure. But his presence here in Purgatory is rock-solid evidence of the mercy of the Savior!

Some background on Manfred: Apart from being the grandson of the empress Constance, as he tells us, Manfred was the illegitimate son of the Holy Roman Emperor, Frederick II and Bianca Lanci and grandson of the Hohenstaufen Emperor, Henry VI. It’s clever of the Poet to have him introduce himself this way, so as to keep an air of propriety. (Recall that Frederick, reputed to be an Epicurean–and therefore a heretic–was mentioned by Farinata in Canto 10 of the Inferno.) Manfred was the last Hohenstaufen king of S icily and ruled there from 1258 until his death in 1266–a year after Dante was born. Thus, it’s odd that he should ask Dante if he recognized him. Like his father before him, he was accused of being an Epicurean. He was urbane, spoke several languages, cultivated an environment of artistic refinement at court, was a composer and patron of the arts, and was, in fact, noted for his handsome bearing. After his father and his half-brother, Conradin, died (he was said to have murdered them!), he crowned himself King of Sicily. His political wranglings and his various battles ran him afoul of the papacy on several occasions, and he was excommunicated twice. At the horrific Battle of Montaperti, he sided with the victorious Ghibellines against the Florentine Guelfs. D ante mentions this battle in Canto 32 of the Inferno when he accidentally (?) kicks one of the frozen traitors in the face. The traitor was Bocca degli Abati who, posing as a Guelf, cut off the hand of the Florentine standard-bearer, who then dropped the signal flag and threw the army into chaos and eventual defeat. (It might be noted here that Dante admired Manfred and his father in spite of their many moral failures because they were enlightened and refined rulers.) At Manfred’s last battle–at Benevento, ne ar Naples–he was both betrayed by his nobles and outnumbered by his enemies. Before he was killed on the battlefield, he most likely received the two wounds he shows to Dante. Because he was excommunicated, though, he was denied a Christian burial in holy g round, and he was buried on the battlefield where he died. There is a wonderful legend at this point that each enemy soldier who passed his grave laid a stone at the spot out of respect. Later, Pope Clement IV ordered the local Archbishop to unearth Manfred ’s body and bury it outside the kingdom along the banks of the Verde River, as though to have done with the likes of him for good!

5. Manfred’s daughter was also named Constance. She married Peter III of Aragon.

6. This would be Cardinal Bartolomeo Pignatelli who was the Archbishop of Cosenza at the time. Cosenza being in the northern part of the province of Calabria.

7. Latin, contumācia, contumāx, “refusing to appear in a court of law in disobedience of a summons".

Top of page