Dante's Divine Comedy: Purgatorio

Canto XV

Dante is dazzled by the Angel of Generosity shining from the West, who effaces the second P and leads him through the Pass. As they are proceeding the singing of Beati Misericordes can be beard behind them. Virgil delivers his first great speech on Love. At the entrance to the Third Cornice, where the sin of Wrath is purged, Dante is shown three visions of the virtue of Meekness—the finding of the Christ child in the temple; Pisistratus forgiving the man who embraced his daughter, and the martyrdom of Saint Stephen. Thick, black smoke, the penance of the Wrathful suddenly envelops the poets from across the terrace.

As much as 'twixt the close of the third hour

And dawn of day appeareth of that sphere

Which aye in fashion of a child is playing,

So much it now appeared, towards the night,

Was of his course remaining to the sun;

There it was evening, and 'twas midnight here;[1]

And the rays smote the middle of our faces,

Because by us the mount was so encircled,

That straight towards the west we now were going

When I perceived my forehead overpowered

Beneath the splendor far more than at first,

And stupor were to me the things unknown,

Whereat towards the summit of my brow

I raised my hands, and made myself the visor

Which the excessive glare diminishes.

As when from off the water, or a mirror,

The sunbeam leaps unto the opposite side,

Ascending upward in the selfsame measure

That it descends, and deviates as far

From falling of a stone in line direct,

(As demonstrate experiment and art,)

So it appeared to me that by a light

Refracted there before me I was smitten;

On which account my sight was swift to flee.

"What is that, Father sweet, from which I cannot

So fully screen my sight that it avail me,"

Said I, "and seems towards us to be moving?"

"Marvel thou not, if dazzle thee as yet

The family of heaven," he answered me;

"An angel 'tis, who comes to invite us upward.[2]

Soon will it be, that to behold these things

Shall not be grievous, but delightful to thee

As much as nature fashioned thee to feel."

When we had reached the Angel benedight,

With joyful voice he said: "Here enter in

To stairway far less steep than are the others."

We mounting were, already thence departed,

And "Beati misericordes" was

Behind us sung, "Rejoice, thou that o'ercomest!"[3]

My Master and myself, we two alone

Were going upward, and I thought, in going,

Some profit to acquire from words of his;

And I to him directed me, thus asking:

"What did the spirit of Romagna mean,

Mentioning interdict and partnership?"[4]

Whence he to me: "Of his own greatest failing

He knows the harm; and therefore wonder not

If he reprove us, that we less may rue it.

Because are thither pointed your desires

Where by companionship each share is lessened,

Envy doth ply the bellows to your sighs.

But if the love of the supernal sphere

Should upwardly direct your aspiration,

There would not be that fear within your breast;

For there, as much the more as one says 'Our,'

So much the more of good each one possesses,

And more of charity in that cloister burns."

"I am more hungering to be satisfied,"

I said, "than if I had before been silent,

And more of doubt within my mind I gather.

How can it be, that boon distributed

The more possessors can more wealthy make

Therein, than if by few it be possessed?"[5]

And he to me: "Because thou fixest still

Thy mind entirely upon earthly things,

Thou pluckest darkness from the very light.

That goodness infinite and ineffable

Which is above there, runneth unto love,

As to a lucid body comes the sunbeam.

So much it gives itself as it finds ardor,

So that as far as charity extends,

O'er it increases the eternal valor.

And the more people thitherward aspire,

More are there to love well, and more they love there,

And, as a mirror, one reflects the other.

And if my reasoning appease thee not,

Thou shalt see Beatrice; and she will fully

Take from thee this and every other longing.

Endeavor, then, that soon may be extinct,

As are the two already, the five wounds

That close themselves again by being painful."

Even as I wished to say, "Thou dost appease me,"

I saw that I had reached another circle,

So that my eager eyes made me keep silence.

There it appeared to me that in a vision

Ecstatic on a sudden I was rapt,

And in a temple many persons saw;

And at the door a woman, with the sweet

Behavior of a mother, saying: "Son,

Why in this manner hast thou dealt with us?[6]

Lo, sorrowing, thy father and myself

Were seeking for thee;"--and as here she ceased,

That which appeared at first had disappeared.

Then I beheld another with those waters

Adown her cheeks which grief distils whenever

From great disdain of others it is born,

And saying: "If of that city thou art lord,

For whose name was such strife among the gods,

And whence doth every science scintillate,

Avenge thyself on those audacious arms

That clasped our daughter, O Pisistratus;"

And the lord seemed to me benign and mild[7]

To answer her with aspect temperate:

"What shall we do to those who wish us ill,

If he who loves us be by us condemned?"

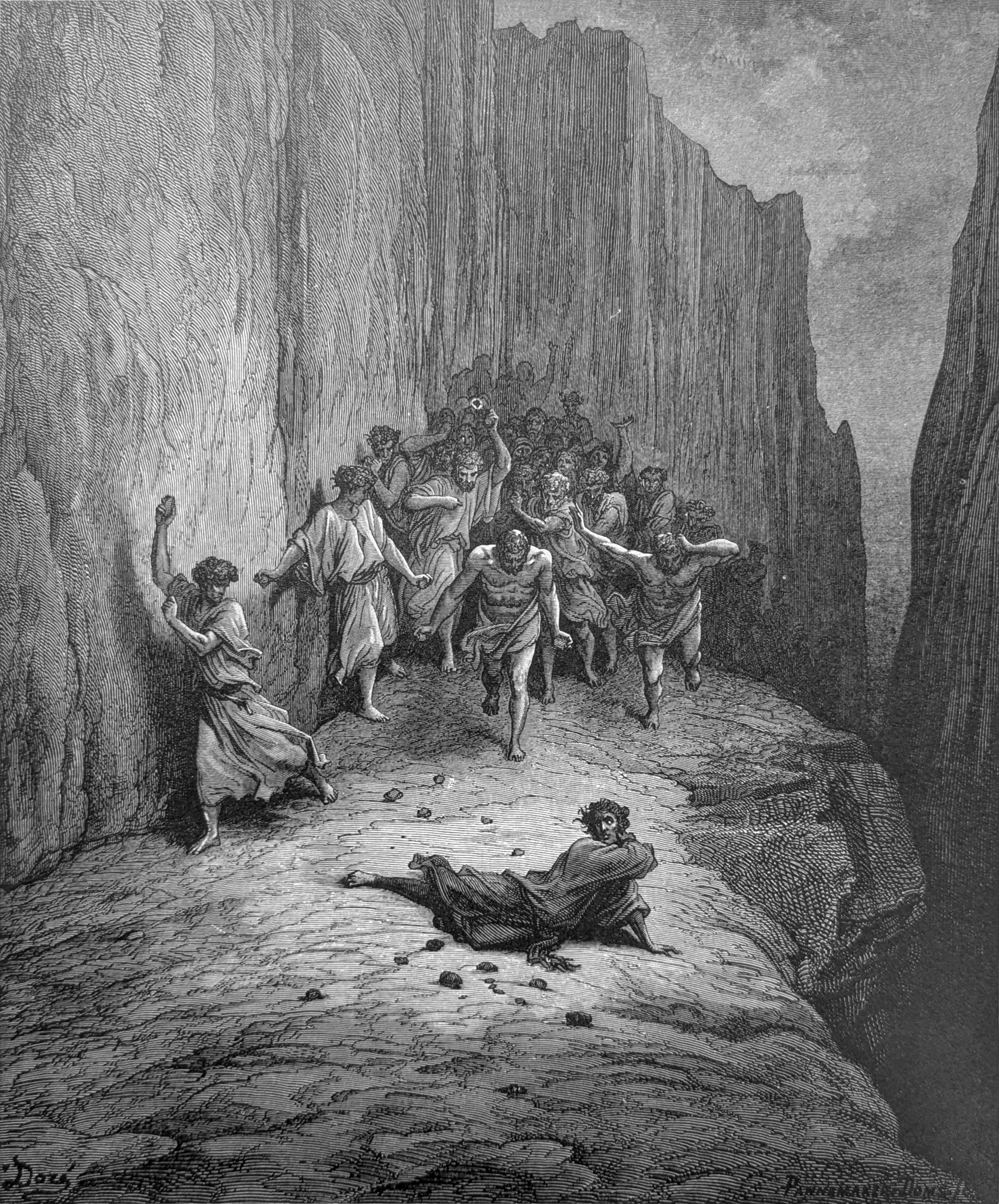

Then saw I people hot in fire of wrath,

With stones a young man slaying, clamorously

Still crying to each other, "Kill him! kill him!"[8]

And him I saw bow down, because of death

That weighed already on him, to the Earth,

But of his eyes made ever gates to heaven,

Imploring the high Lord, in so great strife,

That he would pardon those his persecutors,

With such an aspect as unlocks compassion.

Soon as my soul had outwardly returned

To things external to it which are true,

Did I my not false errors recognize.

My Leader, who could see me bear myself

Like to a man that rouses him from sleep,

Exclaimed: "What ails thee, that thou canst not stand?

But hast been coming more than half a league

Veiling thine eyes, and with thy legs entangled,

In guise of one whom wine or sleep subdues?"

"O my sweet Father, if thou listen to me,

I'll tell thee," said I, "what appeared to me,

When thus from me my legs were ta'en away."

And he: "If thou shouldst have a hundred masks

Upon thy face, from me would not be shut

Thy cogitations, howsoever small.

What thou hast seen was that thou mayst not fail

To ope thy heart unto the waters of peace,

Which from the eternal fountain are diffused.[9]

I did not ask, "What ails thee?' as he does

Who only looketh with the eyes that see not

When of the soul bereft the body lies,

But asked it to give vigor to thy feet;

Thus must we needs urge on the sluggards, slow

To use their wakefulness when it returns."

We passed along, athwart the twilight peering

Forward as far as ever eye could stretch

Against the sunbeams serotine and lucent;[10]

And lo! by slow degrees a smoke approached

In our direction, somber as the night,

Nor was there place to hide one's self therefrom.

This of our eyes and the pure air bereft us.

Illustrations of Purgatorio

Then saw I people hot in fire of wrath, / With stones a young man slaying, clamorously / Still crying to each other, "Kill him, kill him!" Purg. XV, lines 106-108

Footnotes

1. Basically, if it is three hours before sunset at six PM here in Purgatory, it is 3 AM in Jerusalem. And in Italy (Florence) it is three hours earlier, making it midnight there. In “liturgical time,” it is coming on the late afternoon prayer time called Vespers. The Poet’s “playing” with time here also includes light and darkness, themes that will weave through this and the next canto.

2. With the mid-afternoon sun now directly in front of the pilgrims, and aligned with their westward movement, Dante tells us that he was blinded by an even brighter light that he had to shield his eyes from. The source of this light is, of course, the Angel o f Meekness and Generosity. But instead of first questioning what this new light is, Dante, who seems to have forgotten about the angel guardians of each terrace, “blinds” us momentarily from the answer with a diversion about the property of reflected light, which only explains why he shielded his eyes. The sun, we already know, is always a symbol of God and Divine Light. Interestingly, while Dante tells us that the angel’s brightness is greater than that of the sun, this is due, most likely, to the suddenness and unexpected appearance of the angel, and the fact that the angel and the sun are coming at them from the same direction. However, we don’t yet know that this new light is an angel, and this gives the opening of the canto a sense of mystery. At the same time, we need to be reminded that we are leaving the envious sinners and, as Ciardi notes here: “Allegorically, this process of reflection may best be taken for the perfection of outgoing love, which the Angel, as the true opposite of the Envious, represent s.” We will soon see that this “outpouring of love” is the energy that fuels this canto. Furthermore, as we will learn toward the end of the Paradiso, all the angels look perpetually into the face of God and thus reflect the effulgence of that divine Love into the universe. Dante is not yet ready to share the fullness of their vision.

3. The angel’s joy now erases any sense of consternation at his appearance and, incidentally, he (very subtly) erases another P from Dante’s forehead. The pilgrims climb to the singing of the fifth Beatitude from Jesus’ Sermon on the Mount: “Blessed are the merciful, for they shall obtain mercy” (Matthew 5:7). Since the climbers haven’t yet reached the next terrace, we can presume that the Gospel verse is being sung by the envious sinners as part of their “rein,” mercy and compassion being the opposite of envy. At the same time, “Rejoice, you who conquer!” is most likely spoken to Dante by the angel as he removes the P from his forehead. Jesus ends his sermon with the words: “Rejoice and be glad, for your reward will be great in heaven” (Matthew 5:12). Interestingly, this exclamation is also similar to the hymn that Dante hears coming from the great cross of lights in the Paradiso (14:125) when he meets his great-great-grandfather, Cacciaguida: “Arise and conquer!”

Beati Misericordes: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_QF07SrGj1k

Beati Misericordes, quoniam ipsi misericordiam consequentur

Beati mundo corde, quoniam ipsi Deum videbunt.

"Blessed are the merciful, for they shall obtain mercy."

"Blessed are the pure in heart, for they shall see God."

4. This is the first of the three central cantos of the entire Comedy, and Dante’s question, which seems to harken back to the Terrace of Envy, is actually quite significant because it opens up one of the Poem’s central themes: the relation between earthly and heavenly things. He and Virgil are now alone and Dante takes advantage of the moment to unpack the meaning of Guido Del Duca’s statement in the previous canto: “O human race! Why do you go to such lengths to get what you cannot have?” Virgil’s answer, simple as it seems, will be echoed several more times in the Poem.

5. What is happening here is that this is really Dante’s first lesson in how to understand the workings of heaven. By the time we move a few cantos into the Paradiso, it will be clear that earthly ways of thinking-–including some cherished laws of physics–-no longer work there. Here on earth, Virgil tells Dante, there is a limited supply of “things.” Whatever is possessed by others means there’s less for me. Even when we share, what we share is less than the whole. Furthermore, those who spend their lives in pursuit of material gain (which is limited) also live in fear that others will get what I want, and when they get it I lament. This is where Envy enters the heart and begins to poison it. On the other hand, Virgil says, if we focused our energies on the things above we would quickly discover that there’s an endless supply, and sharing them actually increases the supply! Earlier, in his Convivio (III,xv), Dante wrote: “The Saints are free from envy of one another, because each has attained the limit of their desire.”

6. As we’ve become accustomed, a scene from the life of Mary, the mother of Jesus, is always first. This one is taken from the Gospel of Luke (2:41-52). Jesus, now 12 years old, and his family had gone down to Jerusalem from Nazareth for the feast of the Passover. On the way home, his parents missed him, but figured he was with friends somewhere else in the caravan. After three days, they realized this wasn’t the case and went back to Jerusalem. There they found him in the Temple amid the teachers, talking about points of the law. Apparently, he had stayed behind. With every right to be angry with her errant son, Mary takes the high road. An example of meekness to the sinners on this terrace.

7. The second vision is drawn from ancient history with two sources joined together into this one vision. The reference to the city of great learning and wisdom comes from Ovid’s Metamorphoses (VI,70ff) where we read of the contest between Athena and Neptune to name the city of Athens. Interestingly enough, this naming contest is actually part of a larger story that we encountered back in Canto 12 with Arachne challenging Minerva/Athena to a weaving contest. Arachne depicted the dalliances of the gods with mortal women (which offended Minerva), while Minerva depicted the gods in their glory–-herself and Neptune included.

The rest of the vision comes from the 1st century Memorable Acts and Deeds by Valerius Maximus:

“Humanity is of no robust nature, yet we may proclaim the clemency of Pisistratus, tyrant of Athens. When a young man inflamed with love of his maiden daughter, meeting her in the street, kissed her, and therefore his wife wanted him to punish the ma n with death, he replied, ‘If we punish those that love us, what must we do to those that hate us?’ It is incongruous to have to add, that this saying came out of the mouth of a tyrant” (Book I:1e2).

Read broadly, one can hear echoes of the Great Commandment and Jesus’ command to love one’s enemies.

8. This final ecstatic vision is of the stoning of St. Stephen, the first Christian martyr. The long and dramatic story is found in the Acts of the Apostles (6:8-7:60 ). Stephen, a brilliant and articulate follower of Jesus, is arrested for heresy and brought for trial before the Jewish high court. After a long narrative in which he recounts the stiff-necked history of Israel’s many infidelities in their relationship with Yahweh, he ultimately blames his accusers of murdering Christ. The story comes to an amazing conclusion in this way:

“ ‘You stiff-necked people, uncircumcised in heart and ears, you always oppose the holy Spirit; you are just like your ancestors. Which of the prophets did your ancestors not persecute? They put to death those who foretold the coming of the righteous one, whose betrayers and murderers you have now become. You received the law as transmitted by angels, but you did not observe it.’ When they heard this, they were infuriated, and they ground their teeth at him. But he, filled with the holy Spirit, looked up intently to heaven and saw the glory of God and Jesus standing at the right hand of God, and he said, ‘Behold, I see the heavens opened and the Son of Man standing at the right hand of God.’ But they cried out in a loud voice, covered their ears, and rushed upon him together. They threw him out of the city, and began to stone him. The witnesses laid down their cloaks at the feet of a young man named Saul. As they were stoning Stephen, he called out, ‘Lord Jesus, receive my spirit.’ Then he fell to his knees and cried out in a loud voice, ‘Lord, do not hold this sin against them’; and when he said this, he fell asleep.”

Note how Stephen’s compassionate dying words are similar to Jesus’ as he was being crucified: “Father, forgive them, they know not what they do” (Luke 23:34). Dante actually heightens the violence of the drama by inserting the words, “Kill him! Kill him!” which are not in the biblical story. But in St. John’s account of the Passion (19:6), the mob does cry out: “Crucify him! Crucify him!” Note also that Hollander, in his commentary here, points out a progression among the three visions that exemplify meekness , “from a beloved son, to a relative stranger, to one’s enemies.” There’s something here for every angry sinner, as it were.

9. Virgil offers a brief lesson that is rather beautiful to consider: “Open yourself to the waters of God’s peace that flow from Him eternally in heaven.” One can’t help but hear the echoes of Jesus’ words to the Samaritan woman: “He who drinks of the water th at I will give him, shall not thirst forever; but the water that I will give him shall become in him a fountain of water springing up into life everlasting” (John 4:14). Water imagery plays throughout the Poem. In Hell there were the various rivers to be crossed. Here, the Mountain is surrounded by water, and water will appear several more times in this Canticle. Most extraordinarily, and Virgil’s holy thought may be hinting at it, toward the end of the Paradiso (canto 30), Dante and Beatrice will come to a river of light. She will direct him to drink from it. And when he does, his vision is changed such that he can see the entirety of the celestial court! It is a moment not to be missed. No wonder Virgil urges him to resume the journey.

10. Serotine, Latin, sērōtinus, “late; relating to the evening”.