Dante's Divine Comedy: Purgatorio

Canto XXII

Statius takes the visitors out of the Fifth Cornice through the Pass of Pardon and on to the next level. The Angel of Liberality erases the fifth P and blesses those who thirst for righteousness. Statius explains that his sin was not Avarice but the opposite. He also discusses his conversion to Christianity and the penalty be paid for keeping it secret. On the Sixth Cornice, where Gluttony is purged, they behold a fruit-laden tree and a cascade of water. From the tree issues a voice that forbids any eating of the fruit and shouts examples of the virtues of Moderation.

Already was the Angel left behind us,

The Angel who to the sixth round had turned us,

Having erased one mark from off my face;

And those who have in justice their desire

Had said to us, "Beati," in their voices,

With "sitio," and without more ended it.[1]

And I, more light than through the other passes,

Went onward so, that without any labor

I followed upward the swift-footed spirits;

When thus Virgilius began: "The love

Kindled by virtue aye another kindles,

Provided outwardly its flame appear.

Hence from the hour that Juvenal descended

Among us into the infernal Limbo,

Who made apparent to me thy affection,[2]

My kindliness towards thee was as great

As ever bound one to an unseen person,

So that these stairs will now seem short to me.

But tell me, and forgive me as a friend,

If too great confidence let loose the rein,

And as a friend now hold discourse with me;

How was it possible within thy breast

For avarice to find place, 'mid so much wisdom

As thou wast filled with by thy diligence?"

These words excited Statius at first

Somewhat to laughter; afterward he answered:

"Each word of thine is love's dear sign to me.[3]

Verily oftentimes do things appear

Which give fallacious matter to our doubts,

Instead of the true causes which are hidden!

Thy question shows me thy belief to be

That I was niggard in the other life,

It may be from the circle where I was;

Therefore know thou, that avarice was removed

Too far from me; and this extravagance

Thousands of lunar periods have punished.

And were it not that I my thoughts uplifted,

When I the passage heard where thou exclaimest,

As if indignant, unto human nature,

"To what impellest thou not, O cursed hunger

Of gold, the appetite of mortal men?'

Revolving I should feel the dismal joustings.

Then I perceived the hands could spread too wide

Their wings in spending, and repented me

As well of that as of my other sins;

How many with shorn hair shall rise again

Because of ignorance, which from this sin

Cuts off repentance living and in death!

And know that the transgression which rebuts

By direct opposition any sin

Together with it here its verdure dries.

Therefore if I have been among that folk

Which mourns its avarice, to purify me,

For its opposite has this befallen me."

"Now when thou sangest the relentless weapons

Of the twofold affliction of Jocasta,"

The singer of the Songs Bucolic said,[4]

"From that which Clio there with thee preludes,

It does not seem that yet had made thee faithful

That faith without which no good works suffice.[5]

If this be so, what candles or what sun

Scattered thy darkness so that thou didst trim

Thy sails behind the Fisherman thereafter?"[6]

And he to him: "Thou first directedst me

Towards Parnassus, in its grots to drink,

And first concerning God didst me enlighten.[7]

Thou didst as he who walketh in the night,

Who bears his light behind, which helps him not,

But wary makes the persons after him,

When thou didst say: "The age renews itself,

Justice returns, and man's primeval time,

And a new progeny descends from heaven.'

Through thee I Poet was, through thee a Christian;

But that thou better see what I design,

To color it will I extend my hand.

Already was the world in every part

Pregnant with the true creed, disseminated

By messengers of the eternal kingdom;

And thy assertion, spoken of above,

With the new preachers was in unison;

Whence I to visit them the custom took.

Then they became so holy in my sight,

That, when Domitian persecuted them,

Not without tears of mine were their laments;

And all the while that I on Earth remained,

Them I befriended, and their upright customs

Made me disparage all the other sects.

And ere I led the Greeks unto the rivers

Of Thebes, in poetry, I was baptized,

But out of fear was covertly a Christian,

For a long time professing paganism;

And this lukewarmness caused me the fourth circle

To circuit round more than four centuries.

Thou, therefore, who hast raised the covering

That hid from me whatever good I speak of,

While in ascending we have time to spare,

Tell me, in what place is our friend Terentius,

Caecilius, Plautus, Varro, if thou knowest;

Tell me if they are damned, and in what alley."[8]

"These, Persius and myself, and others many,"

Replied my Leader, "with that Grecian are

Whom more than all the rest the Muses suckled,[9]

In the first circle of the prison blind;

Ofttimes we of the mountain hold discourse

Which has our nurses ever with itself.

Euripides is with us, Antiphon,

Simonides, Agatho, and many other

Greeks who of old their brows with laurel decked.

There some of thine own people may be seen,

Antigone, Deiphile and Argia,

And there Ismene mournful as of old.

There she is seen who pointed out Langia;

There is Tiresias' daughter, and there Thetis,

And there Deidamia with her sisters."

Silent already were the poets both,

Attent once more in looking round about,

From the ascent and from the walls released;

And four handmaidens of the day already

Were left behind, and at the pole the fifth

Was pointing upward still its burning horn,

What time my Guide: "I think that tow'rds the edge

Our dexter shoulders it behooves us turn,

Circling the mount as we are wont to do."

Thus in that region custom was our ensign;

And we resumed our way with less suspicion

For the assenting of that worthy soul

They in advance went on, and I alone

Behind them, and I listened to their speech,

Which gave me lessons in the art of song.

But soon their sweet discourses interrupted

A tree which midway in the road we found,

With apples sweet and grateful to the smell.[10]

And even as a fir-tree tapers upward

From bough to bough, so downwardly did that;

I think in order that no one might climb it.

On that side where our pathway was enclosed

Fell from the lofty rock a limpid water,

And spread itself abroad upon the leaves.

The Poets twain unto the tree drew near,

And from among the foliage a voice

Cried: "Of this food ye shall have scarcity."[11]

Then said: "More thoughtful Mary was of making

The marriage feast complete and honorable,

Than of her mouth which now for you responds;

And for their drink the ancient Roman women

With water were content; and Daniel

Disparaged food, and understanding won.[12]

The primal age was beautiful as gold;

Acorns it made with hunger savorous,

And nectar every rivulet with thirst.

Honey and locusts were the aliments

That fed the Baptist in the wilderness;

Whence he is glorious, and so magnified

As by the Evangel is revealed to you."

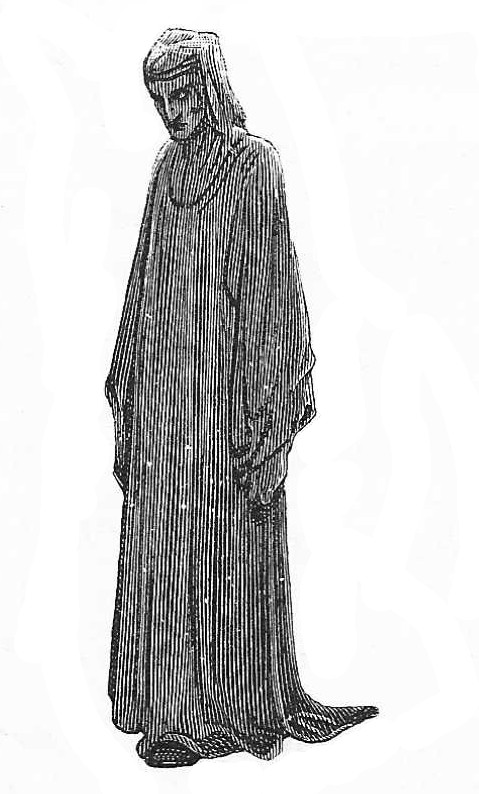

Illustrations of Purgatorio

Dante

Footnotes

1. While removing this P, the angel quotes from the fourth of the Beatitudes noted in St. Matthew’s Gospel (5:6): “Blessed are they who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they shall be filled.” However, the verse is actually truncated so that it would re ad: “Blessed are they who…thirst for righteousness.” This makes sense for the avaricious who thirsted for material wealth. The “hunger” part of the verse will make sense on the Terrace of Gluttony to which we are headed.

2. Decius Junius Juvenal (47-130AD) was a famous Roman satirist who was born 2 years after Statius and outlived him by 34 years. We really don’t know whether they were friends, but Statius, who often flattered the emperor Domitian in his poetry (Juvenal apparently hated the emperor), was apparently the object of one of Juvenal’s satires against Rome’s extravagance and its flattery. Dante seems to have known the Satires and noted Juvenal in some of his prose writings. In the Seventh Satire, Juvenal alludes to Statius’s poverty, but there is nothing historically to back this up. Juvenal writes there:

“When Statius made Rome happy, and fixed on a date, Everyone rushed to hear his fine voice, and the lines Of his dear Thebaid: the crowd’s hearts were captured By the sweetness he affected, listening there, in ecstasy. And yet, when he’d stunned the audience with his verses, He’d starve, unless he sold his virgin Agave [a pantomime] to Paris [a mime]…”

3. Hollander quotes Benvenuto da Imola here: “Statius now smiles at Virgil’s mistake just as Dante had smiled, earlier, at Statius’s mistake.” When he replies he gives us new information about how sins are punished in Purgatory. Before he answers, though, he reminds Virgil that appearances can be deceiving unless one knows the truth that is within. Virgil had assumed (most likely, Dante, too) that the sin was avarice. But it’s exactly the opposite, Statius tells him candidly. His sin was prodigality, which, I suspect, most of us don’t think about as being sinful. In this case, we, too, tend to judge by appearances until we know the truth.

Then comes something quite unexpected. Statius tells Virgil that he might well have been in Hell with the misers and spendthrifts (Canto 7) if he hadn’t read a passage in his Aeneid (Book 3:55-58). Like avarice, prodigality is an over-concern for material things, but manifested by a riotous, careless style of living rather than greed and grabbing so often characteristic of avarice. As noted above, however, we have no historical evidence to make any claims about Statius’s financial condition. Juvenal teased him about being poor, but that was in the context of satire.

4. The “fatal conflict between Jocasta’s twin sons” is a reference to one of the most famous ancient Greek stories involving Oedipus. Oedipus’ father, Laius, had been warned by an oracle from Delphi not to have a child or it would grow up to kill him and marry his wife, Jocasta. Laius failed to heed the warning, but thinking he could evade the prophecy, he gave the child to a shepherd to expose it on a mountainside. Instead, the shepherd raised Oedipus, who later returned to do exactly what the Delphic oracle ha d predicted.

Unwittingly marrying his mother, Jocasta, she produced the twins Eteocles and Polynices. Later, when the incest was revealed, Oedipus, now King, blinded himself and spent the rest of his life in exile. In the meantime, Eteocles and Polynices were left to sh are the rule of Thebes, each one on alternating years. But Eteocles refused to surrender the throne after the first year, which led to the famous war of the Seven against Thebes, during which the twins killed each other in hand-to-hand combat as they had be en doomed to do by their father’s curse.

The Bucolics are a series of ten pastoral poems called Eclogues, written by Virgil with mostly rural themes. John Ciardi notes in his commentary here that, “this is the first time that Virgil has been cited as the author of any work except the Aeneid.” In a moment, one of these poems will become quite important to the conversation here.

5. Clio was the Muse of History, and Statius invoked her aid at the beginning of his famous epic, the Thebaid, about the war of the Seven against Thebes (which preceded the Trojan War by a generation). Statius also set out to write an epic about Achilles (the Achilleid) but died before he could finish it.

6. Here, Virgil doesn’t think Statius was a Christian when he wrote the Thebaid (close to a hundred years after Virgil died) and wants to know what inspired his conversion (“… travel with the great Fisherman”–-a reference to St. Peter). In a sense, Statius’ epic poem isn’t really the major focus in this conversation, except that Virgil has a rather convoluted way of addressing Statius by way of that poem. Virgil, of course, could not have read the Thebaid himself, though some commentators suggest that Dante treats him as if he had. But he obviously knows about it–-most likely from other Roman poets who arrived in Limbo after it had been written. Dante must surely have read it and he must have had an admiration for Statius, bringing him into the Poem as he does in these cantos (and for the rest of the Purgatorio), and even comparing him with the post-Resurrection Christ in the previous canto. It’s also interesting to consider that just as Virgil saved Dante as his guide and mentor in the Comedy, it was Virgil ’s poetry that saved Statius.

7. The opening reference to Parnassus takes us to the famous mountain by that name in Greece. Mythologically, it was a place sacred to the god Apollo and also inhabited by the Muses: appropriate here because the Muse of Poetry, Calliope, lived among them. On t he mountain, near Delphi, was also the sacred fountain of Castalia to which Statius refers. Virgil, having already drunk from that sacred fountain, inspired Statius to do the same. Furthermore, and without his realizing it, Virgil himself was the “light fro m Heaven” that led Statius to the Christian faith.

8. Terence, Plautus, Caecilius, and Varius were Roman playwrights and are with Virgil in Limbo. Varius was a close friend of Virgil’s and one of the editors of the Aeneid after Virgil’s death. Dante’s exposure to them would probably have been through the Rom an poet Horace.

9. As Statius finished the story of his conversion, he asked Virgil (his heavenly light) about four other pagan Roman writers: Terrence, Plautus, Caecilius, and Varius (see the note above). Responding, Virgil adds 14 more famous figures from antiquity. Keeping in mind the idea of Virgil as the prophet of the Christian era, Ronald Martinez notes here in his commentary: “Along with Limbo (Inf. 4.79-144), this is the most extensive catalogue of classical figures in the Comedy; both lists include historical person ages (in Inferno 4 mostly political figures and philosophers, here exclusively poets) and characters of myth (here figures from Statius’s poems). They are a reminder of the richness of classical civilization, both Greek and Latin, culminating in Virgil, which prepared for the advent of Christianity.” At the same time, the careful reader will recall that Manto, the daughter of Tiresias, was highlighted among the fortune-tellers in Inferno 20. But here Statius places her in Limbo, causing difficulties for interpreters ever since. Robert Hollander, in his commentary, lays the problem out clearly: “… [this causes] a terrible problem for Dante’s interpreters, the sole ‘bi-location’ in his poem. Did he, like Homer, ‘nod’? Are we faced with an error of transcription? Or did he intentionally refer here to Statius’s Manto, while Virgil’s identical character is put in hell?” In the end, we just don’t know.

A Who’s Who in order of mention:

• Persius: Roman satirist.

• Homer: greatest of the Greek epic poets.

• Euripides: Greek playwright.

• Antiphon: Greek playwright.

• Simonides: Greek playwright.

• Agathon: friend of Plato and Socrates; speaks in Plato’s Symposium; no surviving works.

The following characters are mentioned in Statius’s Thebaid and Achilleid:

• Antigone: Daughter of Oedipus and Jocasta, sister of Ismene and of Eteocles and Polynices.

• Deiphyle: wife of Tydeus (one of the Seven against Thebes) and mother of Diomedes (comrade of Ulysses).

• Argia: daughter of Deiphile and wife of Polynices.

• Ismene: Daughter of Oedipus and Jocasta, sister of Antigone and of Eteocles and Polynices.

• Hypsipyle: granddaughter of the god Dionysius, queen of Lemnos.

• Thetis: mother of Achilles.

• Manto: daughter of Tiresias the seer.

• Deidamia: wife of Achilles.

10. This unusual tree and the water falling down upon it from above is one of the stranger sights we’ve seen in Purgatory. From the way it’s described, we might, at first, think it’s actually upside-down. But the text gives us no indication that this is the case, although some commentators through the ages have stated that it was upside-down. And there are some late Medieval illustrations showing an actual upside-down tree with its roots in the air. But since Dante himself suggests that the tree’s unusual tapering is probably intended to keep the souls from climbing it (though we haven’t seen any of them yet), it may be that the branches actually get longer toward the top and bend downward instead of upward. This would make it hard to climb.

Though we have not been told yet, we can correctly assume that the three poets have now arrived at the Terrace of Gluttony. The lush evergreen tree, filled with fruit, and splashed with abundant water from above will be symbolic and play directly into the contrapasso for the sinners we will meet on this Terrace.

11. The mystic voice that shouts from the tree (it is never identified) completes the way Dante structures our fascination. One is reminded here of the injunction in Genesis (2:17) where God forbids Adam and Eve to eat from the Tree of Knowledge. This is immediately followed by a series of examples of temperance and moderation, beginning, as always, with the virtue of Mary, the mother of Jesus. His first miracle in the Gospel of St. John (2:1-11) takes place at a wedding celebration. Seeing that the hosts had run out of wine, Jesus’s mother brought this to his attention and he changed water into wine. Note how Mary’s compassion for the bride and groom is highlighted here and how the voice tells the poets that that same compassion pleads on our behalf in heaven.

12. Following this, other examples of moderation are given, all of which comprise the “whip” of Gluttony (virtues opposed to the sin) that ends this canto. The first is actually noted in St. Thomas Aquinas’ Summa Theologica (2a 2ae q. 149 a. 4)-–in ancient Rome, women drank water instead of wine. Second, Daniel, in the Book of Daniel (1:17), was given wisdom and understanding when he refused to blaspheme and eat the food the king sent to him. The third example comes from Ovid’s Metamorphoses (1:103ff): early humans in the Golden Age satisfied themselves with acorns and water. And, finally, John the Baptist ate locusts and wild honey as noted in St. Matthew’s Gospel (3:4).

Top of page