Dante's Divine Comedy: Purgatorio

Canto IX

Dante dreams that he is being carried away by an eagle but it is Saint Lucia, one of the three blessed ladies from Hell's Canto II, who is bearing him up to the Angel of the Church at Peter's Gate. Dante is invited to walk up the gate's steps (symbolizing the three parts of penitence—confession, contrition and satisfaction). With his sword, the angel marks the seven capital sins as Ps (for peccatum or 'sin') on Dante's forehead. One at a time, each P will be erased as his soul is purged of that particular sin. The poets enter Purgatory to the strains of the hymn Te Deum Laudamus.

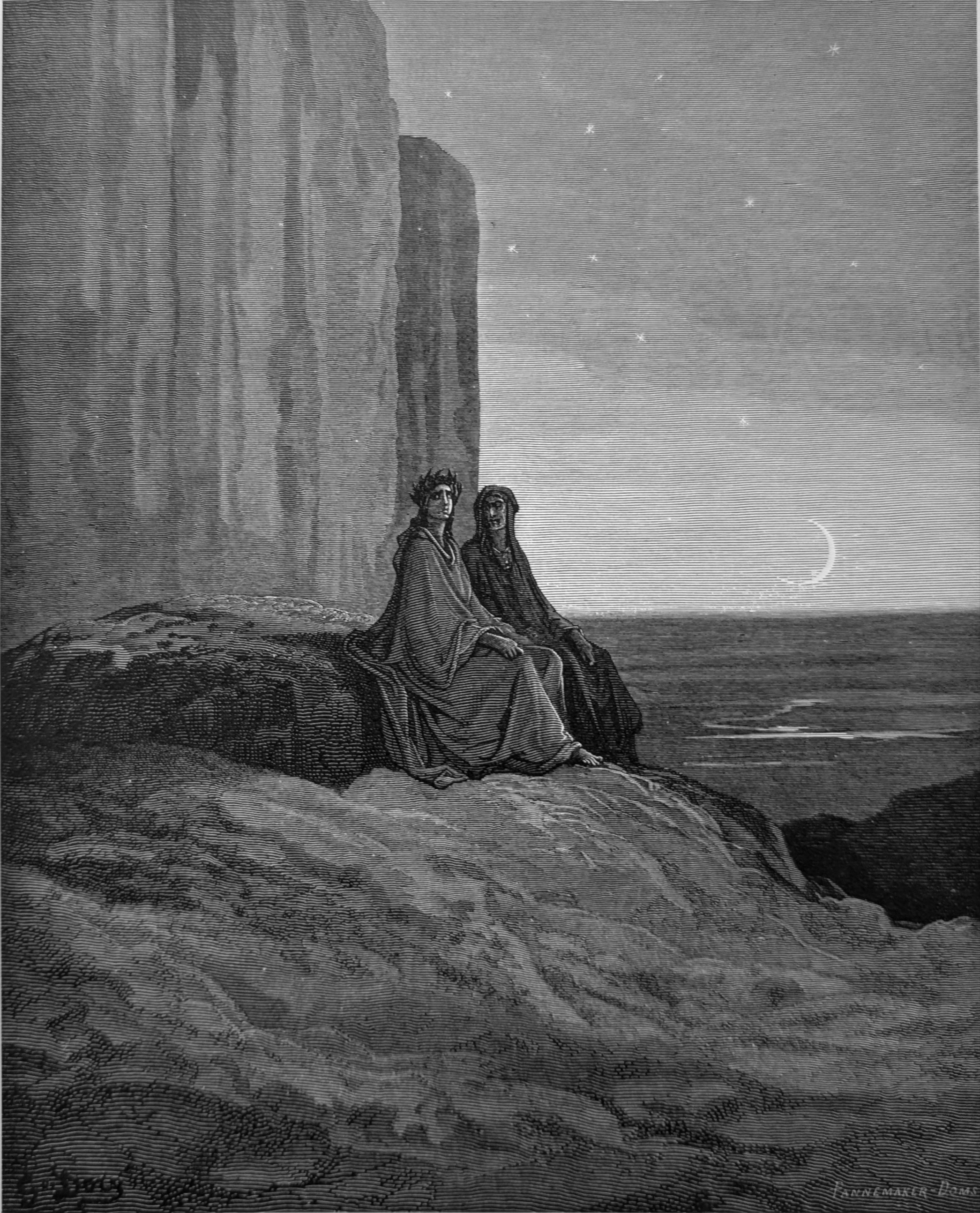

The concubine of old Tithonus now

Gleamed white upon the eastern balcony,

Forth from the arms of her sweet paramour;[1]

With gems her forehead all relucent was,

Set in the shape of that cold animal

Which with its tail doth smite amain the nations,

And of the steps, with which she mounts, the Night

Had taken two in that place where we were,

And now the third was bending down its wings;

When I, who something had of Adam in me,

Vanquished by sleep, upon the grass reclined,

There were all five of us already sat.

Just at the hour when her sad lay begins

The little swallow, near unto the morning,

Perchance in memory of her former woes,[2]

And when the mind of man, a wanderer

More from the flesh, and less by thought imprisoned,

Almost prophetic in its visions is,

In dreams it seemed to me I saw suspended

An eagle in the sky, with plumes of gold,

With wings wide open, and intent to stoop,[3]

And this, it seemed to me, was where had been

By Ganymede his kith and kin abandoned,

When to the high consistory he was rapt.

I thought within myself, perchance he strikes

From habit only here, and from elsewhere

Disdains to bear up any in his feet.

Then wheeling somewhat more, it seemed to me,

Terrible as the lightning he descended,

And snatched me upward even to the fire.

Therein it seemed that he and I were burning,

And the imagined fire did scorch me so,

That of necessity my sleep was broken.

Not otherwise Achilles started up,

Around him turning his awakened eyes,

And knowing not the place in which he was,[4]

What time from Chiron stealthily his mother

Carried him sleeping in her arms to Scyros,

Wherefrom the Greeks withdrew him afterwards,

Than I upstarted, when from off my face

Sleep fled away; and pallid I became,

As doth the man who freezes with affright.

Only my Comforter was at my side,

And now the sun was more than two hours high,

And turned towards the sea-shore was my face.

"Be not intimidated," said my Lord,

"Be reassured, for all is well with us;

Do not restrain, but put forth all thy strength.

Thou hast at length arrived at Purgatory;

See there the cliff that closes it around;

See there the entrance, where it seems disjoined.

Whilom at dawn, which doth precede the day,

When inwardly thy spirit was asleep

Upon the flowers that deck the land below,

There came a Lady and said: 'I am Lucía;

Let me take this one up, who is asleep;

So will I make his journey easier for him.'[5]

Sordello and the other noble shapes

Remained; she took thee, and, as day grew bright,

Upward she came, and I upon her footsteps.

She laid thee here; and first her beauteous eyes

That open entrance pointed out to me;

Then she and sleep together went away."

In guise of one whose doubts are reassured,

And who to confidence his fear doth change,

After the truth has been discovered to him,

So did I change; and when without disquiet

My Leader saw me, up along the cliff

He moved, and I behind him, tow'rd the height.

Reader, thou seest well how I exalt

My theme, and therefore if with greater art

I fortify it, marvel not thereat.

Nearer approached we, and were in such place,

That there, where first appeared to me a rift

Like to a crevice that disparts a wall,

I saw a portal, and three stairs beneath,

Diverse in color, to go up to it,

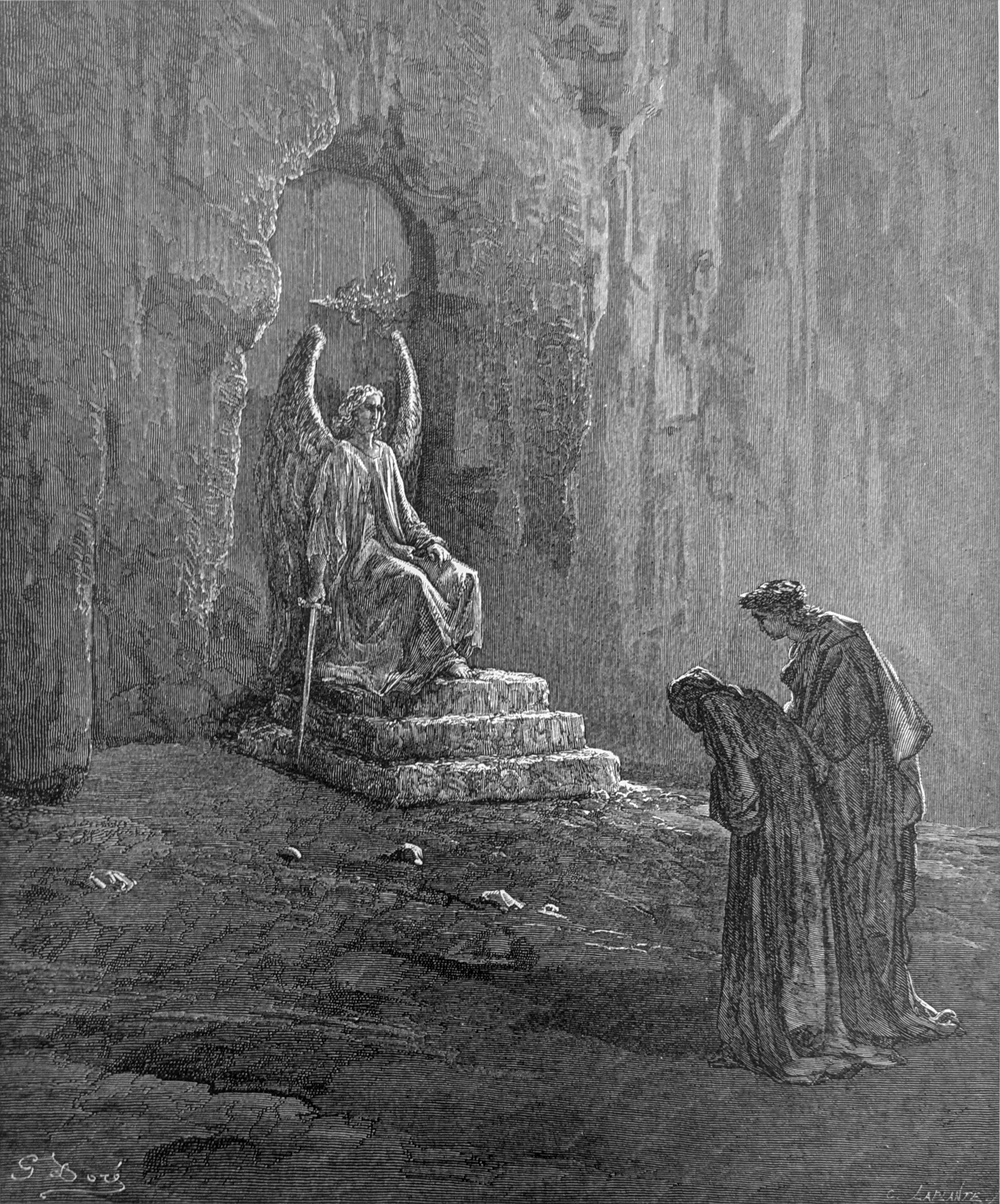

And a gate-keeper, who yet spake no word.[6]

And as I opened more and more mine eyes,

I saw him seated on the highest stair,

Such in the face that I endured it not.

And in his hand he had a naked sword,

Which so reflected back the sunbeams tow'rds us,

That oft in vain I lifted up mine eyes.

"Tell it from where you are, what is't you wish?"

Began he to exclaim; "where is the escort?

Take heed your coming hither harm you not!"

"A Lady of Heaven, with these things conversant,"

My Master answered him, "but even now

Said to us, 'Thither go; there is the portal.' "[7]

"And may she speed your footsteps in all good,"

Again began the courteous janitor;

"Come forward then unto these stairs of ours."

Thither did we approach; and the first stair

Was marble white, so polished and so smooth,

I mirrored myself therein as I appear.[8]

The second, tinct of deeper hue than perse,

Was of a calcined and uneven stone,

Cracked all asunder lengthwise and across.

The third, that uppermost rests massively,

Porphyry seemed to me, as flaming red

As blood that from a vein is spirting forth.

Both of his feet was holding upon this

The Angel of God, upon the threshold seated,

Which seemed to me a stone of diamond.

Along the three stairs upward with good will

Did my Conductor draw me, saying: "Ask

Humbly that he the fastening may undo.

Devoutly at the holy feet I cast me,

For mercy's sake besought that he would open,

But first upon my breast three times I smote.

Seven Ps upon my forehead he described

With the sword's point, and, "Take heed that thou wash

These wounds, when thou shalt be within," he said.

Ashes, or earth that dry is excavated,

Of the same color were with his attire,

And from beneath it he drew forth two keys.[9]

One was of gold, and the other was of silver;

First with the white, and after with the yellow,

Plied he the door, so that I was content.[10]

"Whenever faileth either of these keys

So that it turn not rightly in the lock,"

He said to us, "this entrance doth not open.

More precious one is, but the other needs

More art and intellect ere it unlock,

For it is that which doth the knot unloose.

From Peter I have them; and he bade me err

Rather in opening than in keeping shut,

If people but fall down before my feet."[11]

Then pushed the portals of the sacred door,

Exclaiming: "Enter; but I give you warning

That forth returns whoever looks behind."[12]

And when upon their hinges were turned round

The swivels of that consecrated gate,

Which are of metal, massive and sonorous,

Roared not so loud, nor so discordant seemed

Tarpeia, when was ta'en from it the good

Metellus, wherefore meager it remained.[13]

At the first thunder-peal I turned attentive,

And "Te Deum Laudamus" seemed to hear

In voices mingled with sweet melody.[14]

Exactly such an image rendered me

That which I heard, as we are wont to catch,

When people singing with the organ stand;

For now we hear, and now hear not, the words.

Illustrations of Purgatorio

The concubine of old Tithonus now / Gleamed white upon the eastern balcony, Purg. IX, lines 1-2

Terrible as the lightning he descended, / And snatched me upward even to the fire. Purg, IX, lines 29-30

I saw him seated on the highest stair, / Such in the face that I endured it not. / And in his hand he had a naked sword, Purg. IX, lines 80-82

Footnotes

1.Greek mythology, Tithonus, tɪˈθoʊnəs or Τιθωνός, was the lover of Eos, Goddess of the Dawn. With the prayer of Compline and the drama of the serpent’s appearance now finished Dante begins this wonderful canto of transition with an image of the moon rising bejeweled with the stars that make the constellation of Scorpio. It’s about 9pm, and after an amazing first day in Purgatory he falls asleep with Virgil, Sordello, Nino de’Visconte, and Corrado Malaspina still nearby. Note that it is only in Purgatory (which exists in time) that Dante falls asleep, whereas Hell and Paradise are eternal and sleep is unnecessary.

2. All of this is by of prelude to situating the dream Dante has in this canto. But before he actually discloses his dream he calls to mind the sad singing of swallows before sunrise which–almost universally among commentators–brings to mind the terrible legend of Philomela and Procne recounted in Ovid’s Metamorphoses (6:424-674). It’s fascinating how just a word or two can evoke a story, and sometimes, as in this case, a story with tenuous connections to what is at hand. Nevertheless, Ovid’s stories are amazing and the fact that they are often unforgettable, like this one, bears witness to how a classical text doesn’t die because it retains its ability to speak to and move us from out of the past. Because it is so much a part of the tradition of Dante commentary, let me give a brief summary of the legend.

Philomela and Procne were sisters. Procne’s husband, Tereus, king of Thrace, raped Philomela, and to prevent her from telling anyone about it he cut out her tongue. However, she wove a tapestry which depicted the atrocities committed against her and sent it to her sister, Procne. In horror and revenge, Procne murdered her son, Itys, and, with Philomela’s help, cooked him and fed him to her husband, Tereus. When Tereus discovered what he had eaten, he chased the two women with an ax. But before he could kill t hem the gods turned all three into birds. Tereus was changed into a hoopoe, Philomela a nightingale, and Procne a swallow. And this is the (tenuous) connection with Dante’s reference to the swallow singing mournful songs at dawn. Quite amazing, actually.

3. Dante imagines that he is like the mythical Ganymede, who was taken up to the abode of the gods by Jove disguised as a great eagle, Dante sees a great golden eagle hovering over him with its wings outstretched, ready, it would seem, to snatch him up like Ganymede. Here. the subtle sexual undertones of Ganymede’s kidnapping by Jove links with the sexual violence in the story of Philomela and Procne.

And he talks with himself in his dream as though he might be Ganymede. While that mythical boy was tending his sheep on Mount Ida, Dante is a different Ganymede on Mount Purgatory, where the work at hand is the cleansing of the soul and not the bucolic wanderings of a shepherd. One wonders whether he might have included reference to this myth as a way of seeing himself, like Ganymede, chosen by God for this journey into the realms of the afterlife.

As for the eagle, it symbolizes many things: nobility, power (Rome, empire), authority, courage, freedom, sight, and vision to name a few. Commentators on this canto also link the eagle with God and Heaven, spiritual wisdom, intelligence, and grace. In the Tetramorph (the symbols of the Four Christian Evangelists), the symbol of St. John is an eagle. Several Psalms use the image of the wings of a great bird (God) that provide shelter and safety to the faithful, especially in times of difficulty (e.g., Ps 17:8 ; 36:8; 57:2; 63:8; 91:4). Exodus 19:4 proclaims, “You have seen how I treated the Egyptians and how I bore you up on eagles’ wings and brought you to myself.” And in 1976, Michael Joncas wrote the popular Christian hymn, On Eagle’s Wings, with these lines as the refrain: “And he will raise you up on eagle’s wings, / bear you on the breath of dawn, / make you to shine like the sun, / and hold you in the palm of his hand.”

4. His reference to Achilles comes from the unfinished epic of the Roman poet Statius, the Achilleid (I:247ff). In order to thwart a prophecy that Achilles would be killed in the Trojan War, his mother, Thetis, took the sleeping lad off and hid him on the island of Skyros. She amplified her ruse by dressing him as a girl. Unfortunately, he could not escape the two cunning “detectives,” Ulysses and Diomedes, who tricked him into revealing his identity and lured him away with them to the war. The rest of the story will be completed by Homer. We met Ulysses and Diomedes in Canto 26 of the Inferno in a tongue of flame, suffering for their numerous tricks and frauds. Chiron was Achilles’ tutor. We met him in Canto 12 of the Inferno as chief of the centaurs who guard the violent sinners in the river of boiling blood. Hollander, in his commentary, notes the contrast between Achilles and Dante here: “Achilles is carried down from his mountain homeland to an island from which he will go off to his death; Dante is carried up a mountain situated on an island toward his eventual homeland and eternal life.”

5. For a second time, St. Lucy has come to the Pilgrim’s aid. It was she, in Canto 2 of the Inferno, who was sent by the Blessed Virgin to exhort Beatrice to commission Virgil to guide the lost Dante through all the realms of the afterlife in the hope of saving his almost-lost soul. While Dante dreamed of a great golden eagle carrying him (Ganymede) off into the spheres, it was really Lucy (divine light). We have no sense from the text that she was sent by anyone this time. She seems to be keeping an eye (sight, vision) on Dante and his journey. Representing light and sight, it is no coincidence that she carries the Pilgrim up the Mountain at daybreak. Her last task is to motion with her eyes–again, sight–the proximity of the Gate of Purgatory. Dante is obviously changed by Virgil’s explanations and they begin at once toward the gate, Dante following his mentor.

The story of the martyr St. Lucy of Syracuse in Christian hagiography is a fascinating one. She is one of the more popular early Roman martyrs, executed in Syracuse by the Emperor Diocletian in 304 AD. Among the many strands of her story throughout the centuries we know that she vowed to remain a life-long virgin which enraged her suitor who accused her of being a Christian to the local authorities. Lucy is actually among several virgin martyrs of that era. One needs to understand that women had no real status the society of that time, and to declare oneself a virgin-–apart from being a Christian–-was a crime against the state. Marriage and children were the social foundation of the Empire. Arrested and forced to offer a sacrifice before an image of the Emperor , she refused. She was tortured and died by a sword thrust to her throat. (Note how she was referred to as the “enemy of cruelty” in Inferno 2.) By the 700s she was already included, with several other women martyrs, in the Eucharistic prayers of the Liturgy. She was widely venerated in the Middle Ages and is honored until this day as the patron saint of the blind and those with illnesses of the eyes, most likely because a later strand of her story included having her eyes gouged out as part of her torture. H er relics are venerated at many shrines in Europe and most of her body is enshrined in the church of San Geremia in Venice. She seems to make her first appearance in western literature three times in Dante’s Commedia (once in each of the three Canticles). And there is every reason to believe that Dante himself venerated her as a patron. He also recounts in his Convivio (III:9) that he suffered from a fogginess of his eyes because of too much intense reading. Luckily, he notes, he was able to treat himself wit h rest (including his eyes) and cool compresses.

6. As Dante and Virgil approach the Gate of Purgatory, the Poet addresses the reader directly for the ninth time in the Poem and the second time here in Purgatory. Words like “breadth,” “great theme,” “splendor,” and “subtlety” are signals that give meaning an d context to what we have witnessed on the Mountain up to this point. At the same time, they portend even more to come and with deeper meaning and significance. Close at hand is the ritual at the Gate of Purgatory which we and the Pilgrim must interpret correctly in order to continue. As opposed to the ritual and drama of the previous canto, which was public, the ritual here will be much more personal and only involve the Pilgrim Dante. We will want to remember this brief address as we continue to climb the Mountain and enjoy the Poet’s art as he wraps us more and more in a mantle of wonder as we climb and consider the new sights and new meanings he lays out before us.

As the two travelers continue to climb upward toward the great wall of Purgatory, what they thought earlier was a kind of gap or crack in the face of the Mountain turns out to be an unusual portal–the actual Gate of Purgatory. And as Dante describes it, we understand immediately that this is no ordinary gate. Recall that we encountered the Gate of Hell in Canto 3 of the Inferno. It was certainly larger and more grand than this, with the terrifying three tercets carved above it, ending with the words, “Abandon all hope you who enter here!” Not only this, it had no guard, and it was wide open, ready (sadly) to receive anyone who cared to enter through it. Here, on the other hand, the gate is closed and we have no grand entryway. It’s actually rather narrow, hidden from view, has no inscription over it, and, as we’ll see–contrary to Hell’s gate–there is an angel guard who–in order to pass through–requires participation in a ritual of reconciliation and hope. There are three steps of different colors that lead up to the angel who sits at the threshold of the portal holding a great unsheathed sword. Both the angel’s face and the sword shine so brilliantly that Dante cannot look at them. One is reminded of the Cherubim who was stationed outside the Garden of Eden with a great flaming sword to prevent Adam and Eve from returning after they had been driven out (Genesis 3:24).

7. The lady from Heaven is St. Lucy who, just moments ago, had carried the dreaming Dante up from the Valley of the Kings and laid him, awakening, at the feet of Virgil. Note that Dante the Poet makes a slight error here in Virgil’s recounting of what St. Lucy “told” him. As a matter of fact, she didn’t tell him where the gate was. Noted as she is for the power of her eyes, she merely glanced at the gate with her eyes several lines back and, with a nod of her head in its direction, Virgil knew what she meant.

Recognizing that St. Lucy is one of the company of the Saints, the angel commends the pilgrims to her continued patronage and bids them approach the stairs in front of them.

8. There is much rich symbolism to pay attention to here as Dante and Virgil prepare to pass through the Gate of Purgatory. The three different steps each represent a phase of the Christian Sacrament of Reconciliation (also known as the Sacrament of Confession or Penance.) The first step, white marble, is so highly polished that Dante can see himself reflected in it. This represents the first step in the Sacrament: a deep and careful introspection or examination of one’s conscience; humbly seeing oneself as they truly are, leading to true and sorrowful rejection of one’s sins.

This leads the penitent to the second phase of the Sacrament, the confession of sin at the rough, fire-blackened, bruise-colored second step, cracked across its length and breadth like a cross. Some commentators speak of these characteristics as representing the shame and pain the penitent feels. And like the stone, the penitent also feels him-/herself broken by their sins.

The third stone appears to Dante to be a large slab of blood-red porphyry. How appropriate that, as the third phase of the Sacrament, this symbolizes both the love and mercy of God and the blood of Christ poured out for the forgiveness of sins–-all received in humble gratitude by the penitent. Note how the angel, who holds the dazzling sword (God) sits on the adamantine threshold of the Gate with his feet resting on this slab of red stone.

Adamantine stone, sometimes confused with the properties of diamonds, here represents the authority of the Church, while the angel rests the feet of his authority on the Love inherent in the Beatitudes.

9. The ash-colored robes worn by the presiding angel here signify penitence. Recall how the gorgeous green robes worn by the angels just below in the Valley of the Kings signified hope. Like the others of his kind so far, though, he is far too brilliant for Dante to look at directly.

10. Whether or not he laid aside his shining sword we are not told. But once the angel had carved the seven Ps on Dante’s forehead he reached within his robes and brought out two keys with which he opened the Gate for Dante and Virgil to pass within. But not until he explained their separate uses and the difference between them. This is an important angel. He carries both the sword of God and St. Peter’s keys to the Kingdom of Heaven which were given to him by Jesus in the Gospel (Matthew 16:18f): “And I tell you that you are Peter, and on this rock I will build My church, and the gates of Hell will not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven. Whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.” Dante saw that one of the keys was silver and the other was gold. The silver one went into the lock first, followed by the gold one. Then the gate opened. And here things become somewhat complicated and mysterious. The angel explains that both keys must work in the lock(s) in order for the gate to open. Furthermore, while the gold key is the more precious of the two, it’s the silver one that enables the gold one to work.

11. To “unlock” the riddle of these two mysterious keys we need to understand something about the nature of the Sacrament of Reconciliation. First, the Catholic Church and several of the mainstream Protestant churches have seven Sacraments, each of which is the occasion of a special encounter with Christ: Baptism, Confirmation, Eucharist, Reconciliation, Ordination, Matrimony, and the Anointing of the Sick. For each of these there is a particular ritual conducted by a priest or a bishop, with the exception of Matrimony, in which the couple marry themselves and the priest is merely an official witness. In the Sacrament of Reconciliation, between an opening prayer and the closing absolution, the penitent privately tells the priest–representing Christ–whatever sins they may have committed since the last time they received this Sacrament, especially those (or the one) that are more serious. Before giving absolution the priest might ask a question or offer a point of advice for the penitent. This is followed by a “penance ”–some prayers, or charitable deed, etc. to be done by the penitent. The absolution by the priest/Christ ends the ritual of the Sacrament.

It is before the priest grants absolution that the silver and gold keys come into play–perhaps in the asking of a question or the giving of some advice, or even privately to himself. However it’s done, he determines the penitent’s readiness to receive absolution. This is where the statement of Jesus to Peter in the passage from St. Matthew’s Gospel quoted above fits in: “Whatever you bind on earth will be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth will be loosed in heaven.” In essence, the gold key, the more precious of the two, represents the authority of the Church to forgive sins, which comes from God. The silver key represents the intelligence and discretion (“wisdom and skill,” says the angel) needed by the priest to read the penitent’s heart. Both need to work together to effect the absolution.

Referring to the keys, the angel, almost gratuitously, tells the travelers that St. Peter gave them to him with the command: “Let in more than less, as long as they humbly ask for mercy.” This is wonderful and hopeful, particularly after we have already met several outstanding examples of the mercy of God in Ante-Purgatory. And while they still have to wait to be admitted through the Gate, at least they are saved. We’ll want to remember St. Peter’s words as we climb the Mountain.

12. The angel’s final words are both a welcome and a warning. The warning stands out in particular because we have come across it in Scripture and other places with rather serious consequences. In chapter 19 of the Book of Genesis, we have the destruction of So dom and Gomorrah and the angel’s warning to Lot and his family not to look back as they flee the destruction. Unfortunately, Lot’s wife looks back (v.26) and is turned into a pillar of salt. In Luke’s Gospel (9:62), Jesus lays down a rather severe cost for following him: “No one who puts his hand to the plow and looks back is fit for the kingdom of heaven.”

Dante often quotes from the great St. Augustine, and he obviously has his City of God (Bk. 16, Ch. 30) in mind here as the Saint supports the presentation of absolution he has just given us: “For what is meant by the angels forbidding those who were deliver ed to look back, but that we are not to look back in heart to the old life which, being regenerated through grace, we have put off, if we think to escape the last judgment? Lot’s wife, indeed, when she looked back, remained, and, being turned into salt, furnished to believing men a condiment by which to savor somewhat the warning to be drawn from that example.” Basically, to look back means to go out again, to regress back into the sins we have just confessed.

In mythology, there is also the tragic story of Orpheus and Euridice, whose happy marriage was cut short when Euridice was bitten by a snake and died instantly. Orpheus went down into the Underworld to find her in the hopes that he might bring her back with him. He played so sadly upon his lyre that Hades granted his wish–with one condition: that he not look back. Orpheus agreed, but just steps away from the upper world, he lost faith and turned around. Euridice, who was always behind him, vanished.

13. Interestingly, though, this is not his memory here. Rather, he jumps back to Roman history and the story of Julius Caesar robbing the treasury. Having crossed the Rubicon, he came to Rome with the intent of seizing the vast treasury stored in the Temple of Saturn in order to finance his pursuit of Pompey and Cato. Dante’s source here is Lucan, in his Pharsalia (III, 154-168), who relates that the tribune, one Lucius Caecilius Metellus Creticus, loyal to Pompey, attempted to stop Caesar from breaking open the treasury doors. Faced with such nobility, Caesar half-threatened to kill Metellus, but he was finally convinced by friends to stand aside and let Caesar proceed. He continues:

“Forthwith, Metellus led away, the Temple was opened wide. Then did the Tarpeian rock re-echo, and with a loud peal attest that the doors were opened; then, stowed away in the lower part of the Temple, was dragged up, untouched for many a year, the wealth o f the Roman people, which the Punic wars, which Perseus, which the booty of the conquered Philip, had supplied; that which, Rome, Pyrrhus left to thee in his hurrying flight, the gold for which Fabricius did not sell himself to the king, whatever you saved, manners of our thrifty forefathers; that which, as tribute, the wealthy nations of Asia had sent, and Minoïan Crete had paid to the conqueror Metellus; that, too, which Cato brought from Cyprus over distant seas. Besides, the wealth of the East, and the re mote treasures of captive kings, which were borne before him in the triumphal processions of Pompey, were carried forth; the Temple was spoiled with direful rapine; and then for the first time was Rome poorer than Caesar.”

The Tarpeian Rock was a high cliff not far from the Temple of Saturn, a place used for the execution of major criminals by shoving them off.

14. Dante closes this canto with a deliberate harmonization of the singing of the Te Deum, a late fourth century Christian hymn of unknown origin and authorship, accompanied by the organ and the screeching and creaking of the metal hinges of the Gate of Purgatory against the stone portal which, strangely, he calls a beautiful “new harmony.” Here he is obviously drawing on his experience as a faithful Catholic in terms of the music that is generally part of major Church ceremonies. The Te Deum is a grand and somewhat lengthy hymn of praise in Gregorian chant sung on special occasions, and it makes sense as the musical accompaniment for this special moment when our pilgrims’ enter into Purgatory Proper (as will the Gloria in excelsis later). Dante’s mention of “harmony” here, however strange it might seem, is significant as the marker of another of Purgatory’s overarching virtues. Along with hope, harmony or unity will often stand out as the significant features of the souls’ purgation. The pain (screeching hinges) of purgation will harmonize with the growing beauty (singing) of souls cleansed and repaired before they rise to see God in the face. And what better way to celebrate Dante’s transition than with the sounds of singing accompanied by a great organ. Music is its elf a mode of transit.

Top of page