Dante's Divine Comedy: Purgatorio

Canto XXV

As the three poets venture up the steep and rocky stairs, Dante inquires how the penitent can look so emaciated whilst lacking a physical form. Statius embarks on a scientific and theological lecture about the origin of the rational human soul and its relation to the material body, before and after death. The trio come to a wall of fire, the Seventh Cornice, and hear Summae Deus Clementiae coming from the blaze that is purifying the penitent Lustful. The spirits cry out examples of virgin Chastity, the opposing virtue, and then praise chasteness within marriage.

Now was it the ascent no hindrance brooked,

Because the sun had his meridian circle

To Taurus left, and night to Scorpio;[1]

Wherefore as doth a man who tarries not,

But goes his way, whate'er to him appear,

If of necessity the sting transfix him,

In this wise did we enter through the gap,

Taking the stairway, one before the other,

Which by its narrowness divides the climbers.[2]

And as the little stork that lifts its wing

With a desire to fly, and does not venture

To leave the nest, and lets it downward droop,[3]

Even such was I, with the desire of asking

Kindled and quenched, unto the motion coming

He makes who doth address himself to speak.

Not for our pace, though rapid it might be,

My father sweet forbore, but said: "Let fly

The bow of speech thou to the barb hast drawn."

With confidence I opened then my mouth,

And I began: "How can one meagre grow

There where the need of nutriment applies not?"

"If thou wouldst call to mind how Meleager

Was wasted by the wasting of a brand,

This would not," said he, "be to thee so sour;[4]

And wouldst thou think how at each tremulous motion

Trembles within a mirror your own image;

That which seems hard would mellow seem to thee.

But that thou mayst content thee in thy wish

Lo Statius here; and him I call and pray

He now will be the healer of thy wounds."[5]

"If I unfold to him the eternal vengeance,"

Responded Statius, "where thou present art,

Be my excuse that I can naught deny thee."

Then he began: "Son, if these words of mine

Thy mind doth contemplate and doth receive,

They'll be thy light unto the How thou sayest.

The perfect blood, which never is drunk up

Into the thirsty veins, and which remaineth

Like food that from the table thou removest,

Takes in the heart for all the human members

Virtue informative, as being that

Which to be changed to them goes through the veins

Again digest, descends it where 'tis better

Silent to be than say; and then drops thence

Upon another's blood in natural vase.[6]

There one together with the other mingles,

One to be passive meant, the other active

By reason of the perfect place it springs from;

And being conjoined, begins to operate,

Coagulating first, then vivifying

What for its matter it had made consistent.

The active virtue, being made a soul

As of a plant, (in so far different,

This on the way is, that arrived already,)

Then works so much, that now it moves and feels

Like a sea-fungus, and then undertakes

To organize the powers whose seed it is.[7]

Now, Son, dilates and now distends itself

The virtue from the generator's heart,

Where nature is intent on all the members.

But how from animal it man becomes

Thou dost not see as yet; this is a point

Which made a wiser man than thou once err[8]

So far, that in his doctrine separate

He made the soul from possible intellect,

For he no organ saw by this assumed.

Open thy breast unto the truth that's coming,

And know that, just as soon as in the foetus

The articulation of the brain is perfect,

The primal Motor turns to it well pleased

At so great art of nature, and inspires

A spirit new with virtue all replete

Which what it finds there active doth attract

Into its substance, and becomes one soul,

Which lives, and feels, and on itself revolves.[9]

And that thou less may wonder at my word,

Behold the sun's heat, which becometh wine,

Joined to the juice that from the vine distils.[10]

Whenever Lachesis has no more thread,

It separates from the flesh, and virtually

Bears with itself the human and divine;[11]

The other faculties are voiceless all;

The memory, the intelligence, and the will

In action far more vigorous than before.

Without a pause it falleth of itself

In marvelous way on one shore or the other;

There of its roads it first is cognizant.

Soon as the place there circumscribeth it,

The virtue informative rays round about,

As, and as much as, in the living members.

And even as the air, when full of rain,

By alien rays that are therein reflected,

With divers colors shows itself adorned,

So there the neighboring air doth shape itself

Into that form which doth impress upon it

Virtually the soul that has stood still.

And then in manner of the little flame,

Which followeth the fire where'er it shifts,

After the spirit followeth its new form.

Since afterwards it takes from this its semblance,

It is called shade; and thence it organizes

Thereafter every sense, even to the sight.

Thence is it that we speak, and thence we laugh;

Thence is it that we form the tears and sighs,

That on the mountain thou mayhap hast heard.

According as impress us our desires

And other affections, so the shade is shaped,

And this is cause of what thou wonderest at."[12]

And now unto the last of all the circles

Had we arrived, and to the right hand turned,

And were attentive to another care.[13]

There the embankment shoots forth flames of fire,

And upward doth the cornice breathe a blast

That drives them back, and from itself sequesters.

Hence we must needs go on the open side,

And one by one; and I did fear the fire

On this side, and on that the falling down.

My Leader said: "Along this place one ought

To keep upon the eyes a tightened rein,

Seeing that one so easily might err."

"Summae Deus clementiae," in the bosom

Of the great burning chanted then I heard,

Which made me no less eager to turn round;[14]

And spirits saw I walking through the flame;

Wherefore I looked, to my own steps and theirs

Apportioning my sight from time to time.

After the close which to that hymn is made,

Aloud they shouted, "Virum non cognosco;"

Then recommenced the hymn with voices low.

This also ended, cried they: "To the wood

Diana ran, and drove forth Helice

Therefrom, who had of Venus felt the poison."[15]

Then to their song returned they; then the wives

They shouted, and the husbands who were chaste.

As virtue and the marriage vow imposes.

And I believe that them this mode suffices,

For all the time the fire is burning them;

With such care is it needful, and such food,

That the last wound of all should be closed up.

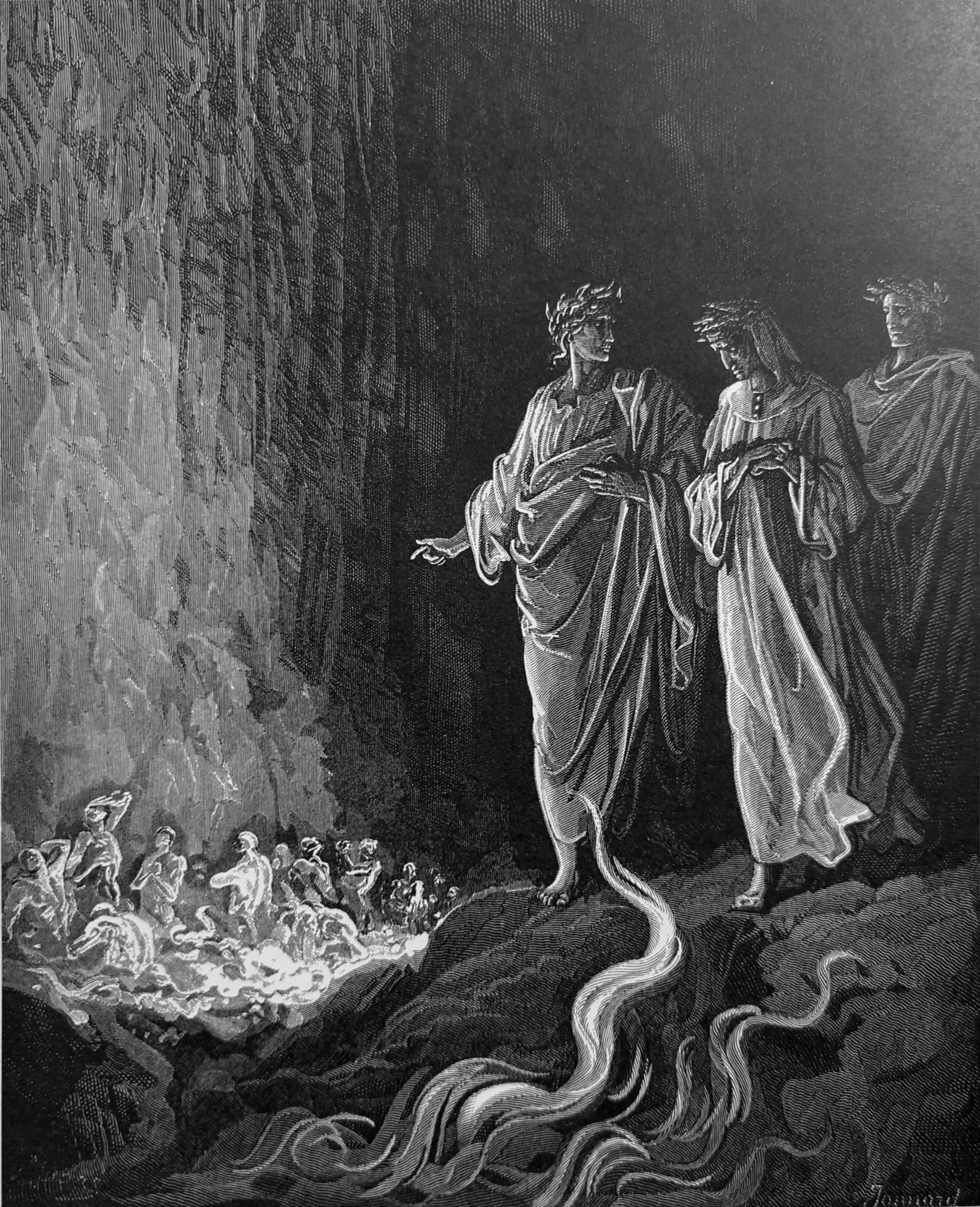

Illustrations of Purgatorio

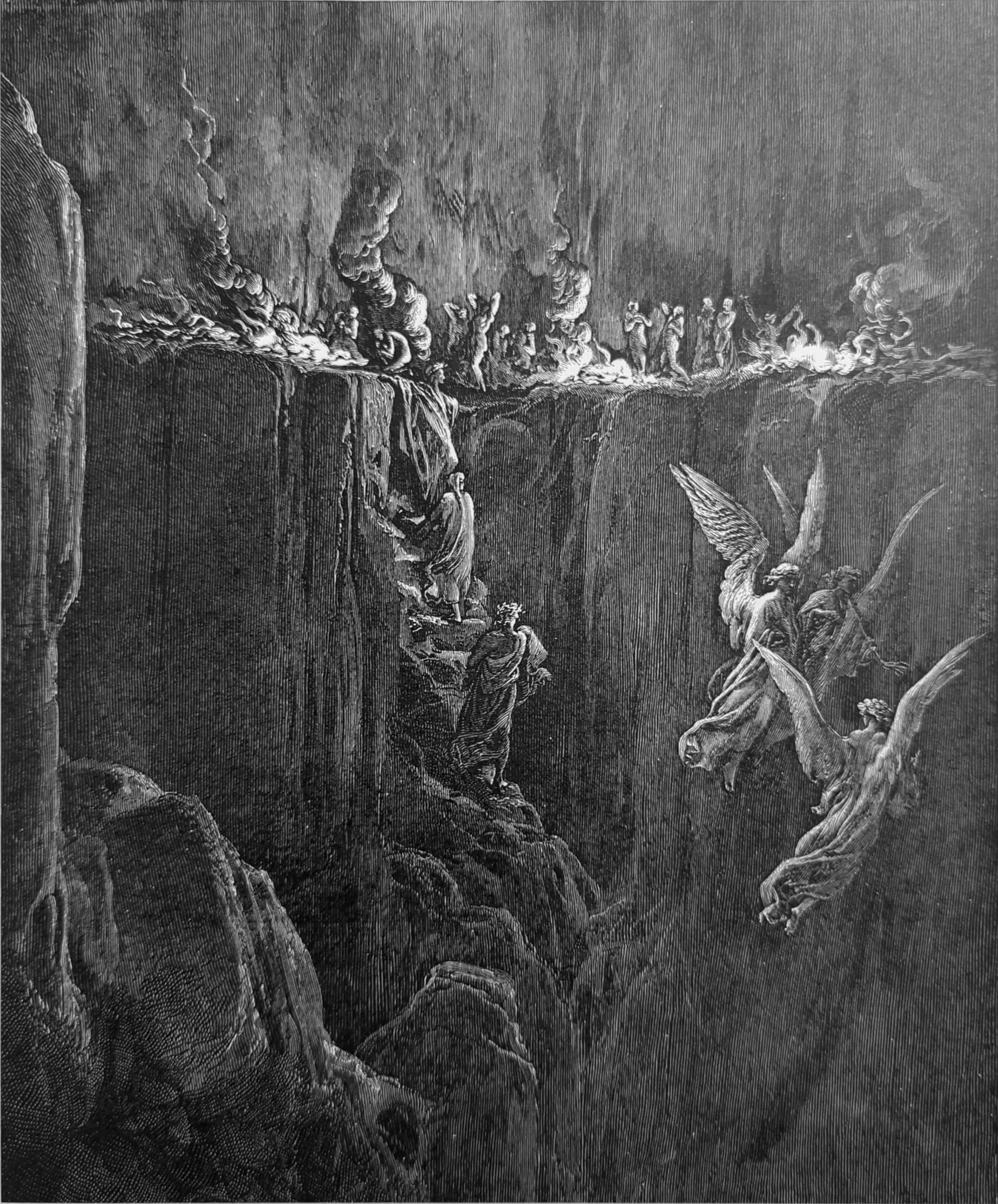

There the embankment shoots forth flames of fire, / And upward doth the cornice breathe a blast / That drives them back, and from itself sequesters. Purg. XXV, lines 112-114

"Summae Deus clementiae," in the bosom / Of the great burning chanted then I heard, / Which made me no less eager to turn round; Purg. XXV, lines 121-123

And spirits saw I walking through the flame; / Wherefore I looked, to my own steps and theirs / Apportioning my sight from time to time. Purg. XXV, lines 124-126

Footnotes

1. Dante is quite precise about the time of day in the opening tercet of this canto, measuring the distance between the constellations Taurus and Scorpio as they move above him. It’s close to 2:00 pm. Robert Hollander works out a very clear picture of the pilgrims’ whereabouts in his commentary here: “Since the travelers had entered this terrace of the gluttons at roughly ten in the morning, it results that they have spent roughly four hours among the penitents of Gluttony and will spend approximately the same a mount of time from now until they leave the penitents of Lust, the first two hours traversing the distance between the two terraces.”

2. Recalling that Forese had warned about wasting time in the previous canto, the three travelers waste no time in moving onward as they begin the steep climb up the stairs to the next terrace. The narrowness of the stairway suggests that they are climbing in single file, and John Ciardi notes here that there’s a significant allegory to be found in the image of the narrow stairs: “… each soul must ultimately climb to salvation alone, inside itself, no matter how much assistance it may receive from others.”

3. In the previous canto, I noted that Dante’s poetry “flies.” Here, he cleverly uses the baby stork image to indicate just the opposite as he struggles with a question he lacks the confidence to ask. Perhaps it’s because there’s now a third party in their group, but Virgil gently urges him to go ahead with his question, using yet another image—that of a tightly drawn bow. Not only does he read Dante’s mind, but he highlights something important about words—perhaps more importantly, about poetic words: they’re like arrows, precise and targeted both for the perfect affect and effect. Visually, there’s also something very physical here so that we don’t get too tangled up in the imagery. It’s a very common situation. Dante has a question. He stops, opens his mouth, draws in his breath, and is ready to speak … but he immediately loses the self-confidence to proceed, and stops. Often this happens with an important question and we’re not sure how to ask it. Not only this. Surely Dante is not the only one with the question he’s about to ask. The attentive reader will, like Dante, already have raised it in his/her head, and will nod in agreement as soon as he lets it fly.

4. No doubt, the connection Virgil wants Dante to understand here is a complicated one. Basically, he wants Dante to see that there is a definite relationship between things that seem to be unrelated-–in this case, the burning log and Meleager’s death. Or, her e among the gluttons, the fact that they are dead but still experience physical hunger, thirst, and emaciation.

Without pause, Virgil immediately offers a second image to help Dante out of his confusion. The image in the mirror and the reality outside of it seem to be separate, yet they are definitely related. Here is how Dorothy Sayers explains the matter in her commentary: “Virgil’s second example is directed to show how a movement may be projected upon an exterior substance (the mirror) without altering that substance, and without material contact between that which moves and that upon which the movement is projected.”

5. Before moving on, Virgil has characterized Dante’s question as a “wound” that Statius—a doctor—will heal. It seems apparent that this “wound” is simply ignorance or a lack of understanding, the bane of the unreflected life and, perhaps, another manifestation of the human condition affected by the sin of our original parents (whose first home is now so close).

6. Basically, Statius explains that: (1) In a man’s body only, there are two kinds of blood: (a) what we think of as “generic” blood, and (b) a special blood that does not circulate throughout the body, but has particular properties that enable it to form and shape a human body. (2) During sexual intercourse, this special (active) blood flows down from the heart (here, Dante follows Aristotle) through the penis in the form of sperm and blends with the (passive) menstrual blood in a woman’s womb. (3) Then, as we will see in a moment, when these two bloods mix and coagulate, the formative (active) work of the male blood begins to work upon the woman’s (passive) blood.

A scientific understanding of how the blood circulates through the body was still several centuries away. In Dante’s time, the male heart was thought to be a kind of container within which, among other things, was a place or chamber for this special blood. Sometimes it was referred to as a lake, as Dante does in verse 20 of Canto 1 of the Inferno. In her commentary here, Dorothy Sayers writes: “the theory that the female’s part in generation was purely passive (the womb being merely as it were the soil that receives the ‘seed’) was almost universally accepted until very recent times, when it became possible to distinguish microscopically the action of the genes in sperm and ovum.”

7. Here begins the second of the three parts of Statius’s exposition: Conception and the Birth of the Human Soul. The active blood of the male mixes with the passive blood of the female and begins to clot it into matter which can be shaped and formed. This is the purpose of the “special blood,” whose active or formative power now becomes the simple plant or vegetative soul. The plant soul would stop here, but the human soul continues in its development. As with other creatures, the vegetative soul gives our bodies animation. But there is still more development needed on the way to a human/immortal soul.

The next stage shows the development of a very simple organism like a primitive sponge which continues toward the goal of a human body/fetus. This creature, still without a human soul, continues to grow and move and feel.

8. Statius takes the opportunity to correct an error of Averroes, a twelfth-century Islamic scholar and philosopher. Every organ in the body has a function and purpose. But Averroes couldn’t find an organ that contained the ability to reason and think (called here the possible intellect, a medieval philosophical term) because it’s not an act or function of a corporeal organ. So, he proposed a kind of universal or transcendent intellect that existed on its own outside of us that we might use as a resource for thinking, but not possess it. This, of course, conflicted with the Christian doctrine that all humans possess intellect, an immortal soul, and free will. Having corrected this error, Statius can continue with his “lecture.”

9. Here, Statius concludes his discussion of how the soul is formed. He has taken us through the development of a simple, primitive, vegetative soul, then to a simple sensitive/sensate soul. When the brain is completed, however, everything changes. At that instant, God, rejoicing in what Nature has done up to this point, breathes his Spirit into the fetus, giving it an immortal soul. Though not yet born, this body-soul human being has all the “equipment,” as it were, that will enable it to sense and to reason. And to think about itself!

10. Earlier, Virgil had offered the examples of Meleager and the mirror. Statius offers a third one here in his analogy of the grape and the wine. The vine grows up out of the earth and produces grapes with the help of the sun, which also turns the juice within the grapes into wine. (As with the circulation of the blood, the process of fermentation had not been discovered in Dante’s time.

11. Lachesis, in ancient Greek religion, was the middle of the Three Fates, or Moirai, alongside her sisters Clotho and Atropos. Normally seen clothed in white, Lachesis is the measurer of the thread spun on Clotho's spindle, and in some texts, determines Destiny. Her Roman equivalent was Decima. Lachesis apportioned the thread of life, determining the length of each lifespan. She measured the thread of life with her rod and is also said to choose a person's destiny during the measurement. Myths attest that she and her sisters appear within three days of a baby's birth to decide the child's fate.

12. In describing the formation of the shade, Statius follows a step-by-step pattern similar to the one he used earlier for human generation. The end-product, the shade, will be as perfect in this new state as it was at the end of its human formation in the womb of its mother.

Enclosed within the new space or “atmosphere” of the afterlife, the heightened powers this soul took with it—memory, intelligence, and will—radiate outward giving the shade an incorporeal form similar to the one it had before it died. The classical literary tradition with which Dante was familiar was filled with shades, spirits, and ghosts, etc., so this transformation was not new to his readers. Here he gives it a kind of Christian foundation. Not to mention the fact that Dante the Poet has given countless generations of readers after him a literary vision of the afterlife, so vivid and realistic, that he has no difficulty in urging, expecting us to take it for real in order to enjoy the full breadth and depth of the experience it presents to us.

13. Table of Sins:

| No | Sins (Pecatto) | Opposites |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Lust | Chastity |

| 2 | Gluttony | Temperance |

| 3 | Avarice (Greed) | Moderation (Generosity) |

| 4 | Sloth | Zeal (Diligence) |

| 5 | Wrath | Meekness |

| 6 | Envy | Generosity |

| 7 | Pride | Humility |

Angels Who Oppose the Sins

1. Chastity

2. Temperance

3. Liberality

4. Zeal

5. Mercy

6. Generosity

7. Humility

Note: Dante travels in reverse direction (7 to 1) as he climbs toward heaven.

Reference: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Seven_deadly_sins

14. The Poet evokes several senses here: he feels the heat, he hears the hymn, and only then does he see the sinners within the flames. All the while, he has to be careful not to be so distracted that he’ll fall off the cliff. Lust is often referred to as a kind of burning, and one can imagine the immense heat the flames generate here. The tenth-century hymn Dante hears is Summae Deus Clementiae, usually sung in the prayers at the Office of Matins early on Saturday mornings. These three verses of the hymn give us the appropriate connection to what Dante experiences here:

1. O God of highest mercy, \ Creator of the fabric of the world, \ You are Three in your gracious divinity, \ And One in the strengthening of all things.

2. Kindly receive our tears \ With holy hymns, \ That with our heart purged of lust, \ We may enjoy you more and more.

3. Burn from our loins / Whatever needs purifying, \ That clothed with the fire of love / We may enjoy you more and more.

As usual, Dante’s curiosity gets the better of him, and hearing this lovely hymn, his “burning desire” leads him to peer deeply into the flames to see where the singing is coming from.

15. As with all the terraces below, pertinent examples of virtue of chastity (the “whip”) and its vices (the “rein” of chastity) are heard here as part of the sinners’ penitential program. As usual, the first refers to Mary the mother of Jesus, and comes from t he scene in St. Luke’s Gospel (1:34) where the angel Gabriel tells her that she is to be the mother of Jesus. She wonders about this and tells the angel, “I know not man” (Virum non cognosco), meaning that she’s not married. Then a pattern begins: the hymn is repeated, followed by another example of chastity. This one comes from Ovid’s Metamorphoses (II: 401-507), and tells the story of the rape of Helice by Jupiter. Helice was one of the forest nymphs of Diana, the chaste virgin goddess. When it was discovered that the nymph was pregnant, Diana drove her out of the forest so as not to corrupt the other chaste nymphs. When Helice bore a son, Jupiter’s wife, Hera, in a fit of jealousy, turned the boy into a bear. Having the last word, Jupiter turned both the boy and his mother into the Bear Constellations, Ursa Major and Ursa Minor. Following another singing of the hymn, the fiery souls sing in praise of those who are married and keep their vows. Note how Dante’s examples move from the praise of virginity to the praise of sexuality within the bonds of marriage.

Top of page