Dante's Divine Comedy: Purgatorio

Canto XXXI

Beatrice's rebuke prompts Dante to confess his sins before fainting with shame. On regaining consciousness, he finds Matilda pulling him towards the river Lethe to plunge his head in so that he is forced to drink—all remembrance of sin will now be forgotten. The Cardinal Virtues take him to Beatrice. Dante gazes into the eyes of his beloved, where he sees the reflection of the split nature of the Griffin which mirrors the duality (human,divine) of God's Incarnate Love for us through the figure of Christ. A mystical union takes place between Dante and Beatrice accompanied by the prayers of the Theological Virtues.

"O thou who art beyond the sacred river,"

Turning to me the point of her discourse,

That edgewise even had seemed to me so keen,[1]

She recommenced, continuing without pause,

"Say, say if this be true; to such a charge,

Thy own confession needs must be conjoined."[2]

My faculties were in so great confusion,

That the voice moved, but sooner was extinct

Than by its organs it was set at large.

Awhile she waited; then she said: "What thinkest?

Answer me; for the mournful memories

In thee not yet are by the waters injured."

Confusion and dismay together mingled

Forced such a Yes! from out my mouth, that sight

Was needful to the understanding of it.

Even as a cross-bow breaks, when 'tis discharged

Too tensely drawn the bowstring and the bow,

And with less force the arrow hits the mark,[3]

So I gave way beneath that heavy burden,

Outpouring in a torrent tears and sighs,

And the voice flagged upon its passage forth.

Whence she to me: "In those desires of mine

Which led thee to the loving of that good,

Beyond which there is nothing to aspire to,

What trenches lying traverse or what chains

Didst thou discover, that of passing onward

Thou shouldst have thus despoiled thee of the hope?

And what allurements or what vantages

Upon the forehead of the others showed,

That thou shouldst turn thy footsteps unto them?"

After the heaving of a bitter sigh,

Hardly had I the voice to make response,

And with fatigue my lips did fashion it.

Weeping I said: "The things that present were

With their false pleasure turned aside my steps,

Soon as your countenance concealed itself."[4]

And she: "Shouldst thou be silent, or deny

What thou confessest, not less manifest

Would be thy fault, by such a Judge 'tis known.

But when from one's own cheeks comes bursting forth

The accusal of the sin, in our tribunal

Against the edge the wheel doth turn itself.

But still, that thou mayst feel a greater shame

For thy transgression, and another time

Hearing the Sirens thou mayst be more strong,

Cast down the seed of weeping and attend;

So shalt thou hear, how in an opposite way

My buried flesh should have directed thee.

Never to thee presented art or nature

Pleasure so great as the fair limbs wherein

I was enclosed, which scattered are in earth.

And if the highest pleasure thus did fail thee

By reason of my death, what mortal thing

Should then have drawn thee into its desire?

Thou oughtest verily at the first shaft

Of things fallacious to have risen up

To follow me, who was no longer such.

Thou oughtest not to have stooped thy pinions downward

To wait for further blows, or little girl,

Or other vanity of such brief use.

The callow birdlet waits for two or three,

But to the eyes of those already fledged,

In vain the net is spread or shaft is shot."[5]

Even as children silent in their shame

Stand listening with their eyes upon the ground,

And conscious of their fault, and penitent;

So was I standing, and she said: "If thou

In hearing sufferest pain, lift up thy beard

And thou shalt feel a greater pain in seeing."[6]

With less resistance is a robust holm

Uprooted, either by a native wind

Or else by that from regions of larbas ,

Than I upraised at her command my chin;

And when she by the beard the face demanded,

Well I perceived the venom of her meaning.

And as my countenance was lifted up,

Mine eye perceived those creatures beautiful

Had rested from the strewing of the flowers;

And, still but little reassured, mine eyes

Saw Beatrice turned round towards the monster,

That is one person only in two natures.[7]

Beneath her veil, beyond the margent green,

She seemed to me far more her ancient self

To excel, than others here, when she was here.

So pricked me then the thorn of penitence,

That of all other things the one which turned me

Most to its love became the most my foe.

Such self-conviction stung me at the heart

O'erpowered I fell, and what I then became

She knoweth who had furnished me the cause.

Then, when the heart restored my outward sense,

The lady I had found alone, above me

I saw, and she was saying, "Hold me, hold me."

Up to my throat she in the stream had drawn me,

And, dragging me behind her, she was moving

Upon the water lightly as a shuttle.[8]

When I was near unto the blessed shore,

"Asperges me," I heard so sweetly sung,

Remember it I cannot, much less write it.[9]

The beautiful lady opened wide her arms,

Embraced my head, and plunged me underneath,

Where I was forced to swallow of the water.

Then forth she drew me, and all dripping brought

Into the dance of the four beautiful,

And each one with her arm did cover me.[10]

'We here are Nymphs, and in the Heaven are stars;

Ere Beatrice descended to the world,

We as her handmaids were appointed her.

We'll lead thee to her eyes; but for the pleasant

Light that within them is, shall sharpen thine

The three beyond, who more profoundly look.'

Thus singing they began; and afterwards

Unto the Griffin's breast they led me with them,

Where Beatrice was standing, turned towards us.[11]

"See that thou dost not spare thine eyes," they said;

"Before the emeralds have we stationed thee,

Whence Love aforetime drew for thee his weapons."

A thousand longings, hotter than the flame,

Fastened mine eyes upon those eyes relucent,

That still upon the Griffin steadfast stayed.

As in a glass the sun, not otherwise

Within them was the twofold monster shining,

Now with the one, now with the other nature.[12]

Think, Reader, if within myself I marveled,

When I beheld the thing itself stand still,

And in its image it transformed itself.

While with amazement filled and jubilant,

My soul was tasting of the food, that while

It satisfies us makes us hunger for it,[13]

Themselves revealing of the highest rank

In bearing, did the other three advance,

Singing to their angelic saraband.[14]

"Turn, Beatrice, O turn thy holy eyes,"

Such was their song, "unto thy faithful one,

Who has to see thee ta'en so many steps.

In grace do us the grace that thou unveil

Thy face to him, so that he may discern

The second beauty which thou dost conceal."

O splendor of the living light eternal!

Who underneath the shadow of Parnassus

Has grown so pale, or drunk so at its cistern,[15]

He would not seem to have his mind encumbered

Striving to paint thee as thou didst appear,

Where the harmonious heaven o'ershadowed thee,

When in the open air thou didst unveil?

Illustrations of Purgatorio

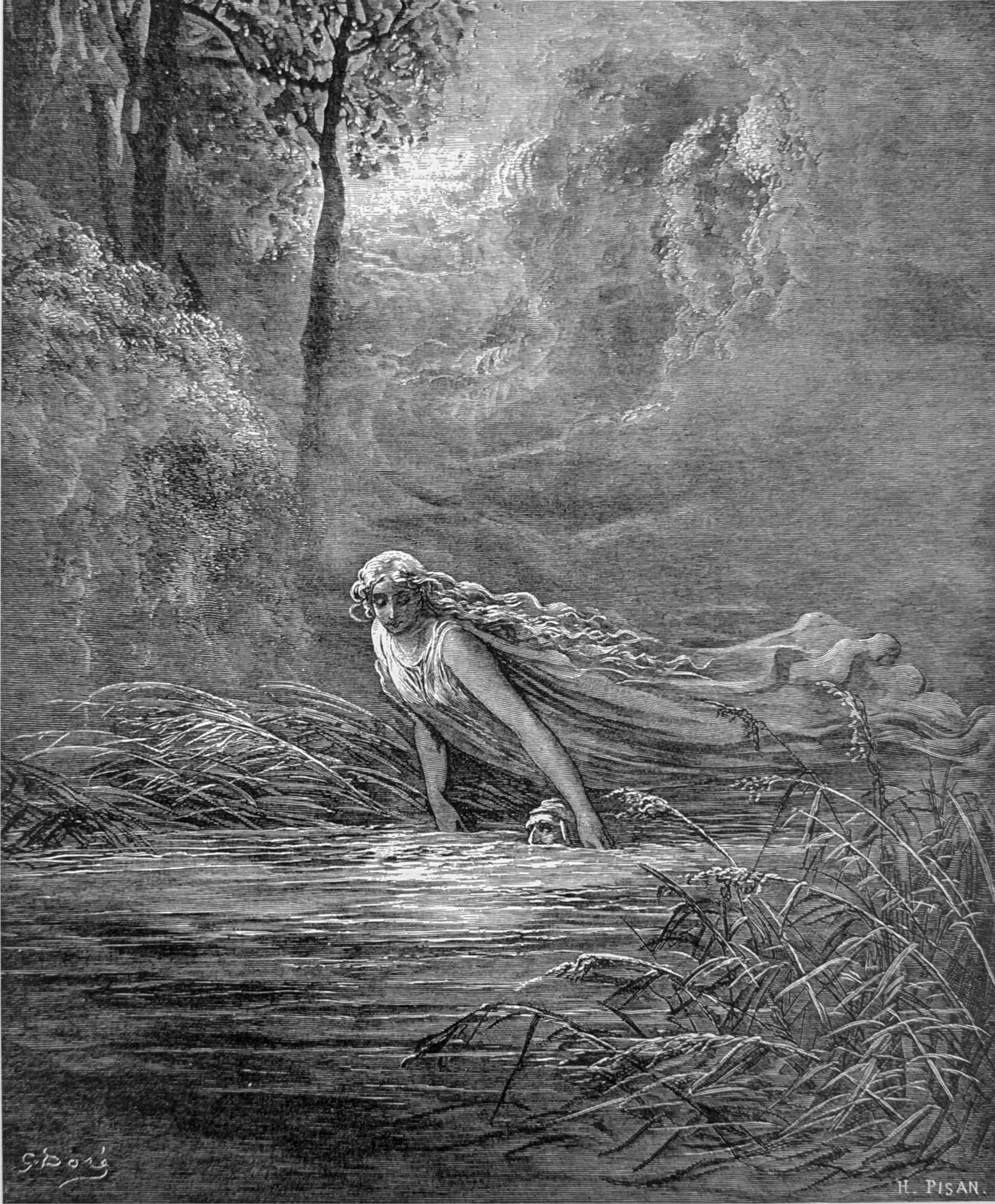

The beautiful lady opened wide her arms, / Embraced my head, and plunged me underneath, / Where I was forced to swallow of the water. Purg. XXXI, lines 100-102

Footnotes

1. The “sacred stream”is the Lethe, whose waters remove from one all remembrance of sin. But we need to understand that Dante is on the other side of this stream, which is itself an image of the break between him and Beatrice. She and the entire mystical pageant are heavenly creatures, and they stand in heaven, as it were, while Dante stands still within this world, the material world, the world of temptation and sin. And so, she will continue to press upon him the need to renounce completely his affection for t hose worldly things that led him astray from love of her.

2. In the midst of this confrontation, let us not forget that, as Dante faces “heaven” across the sacred stream, this is a sacramental moment, the sacrament of penance and reconciliation. One might think of this as the apex, the ultimate purpose of the climb u p the Mountain of Purgatory. Insofar as Beatrice represents Christ and the Eucharist, and the griffin represents Christ in his two natures, and the entire cast of the mystical procession represent the Old and New Testaments, Beatrice, in the name of Christ and the Church, offers forgiveness and absolution if Dante will but acknowledge, that is confess, his failings.

Furthermore, Beatrice reminds Dante that the pain he feels is due to the fact that he still remembers his sins, his failings, his wandering away from her–he is still on the other side of the Lethe, the other side of absolution.

3. The image of the broken crossbow here represents Dante. The bolt or arrow represents his one word. Strained beyond its limits, the crossbow or its string will snap, and Dante is just at that point. While it is hard to conceive that the arrow will go anywhere if the crossbow breaks, he expects us to follow his allusion through. In this case, without much force behind it, the arrow of Dante’s feeble “yes” to Beatrice’s accusations barely reaches her.

4. Here, at last, is Dante’s confession. Compare its simplicity with Beatrice’s long and intense prosecution. Weeping and hardly able to speak, he admits that when she died and, obviously, without her physical presence to support him, he found himself easily distracted by other worldly pursuits and allowed himself to go astray.

5. Beatrice’s reference to the “snares” represented by the various temptations Dante fell for gives the bird image she uses greater significance. His wings were so weighted down by worldly pleasures that he could not soar up to the heavens after her when she died. Note the bite in her remark when she tells him that a more mature bird would have avoided all obstacles and soared up after her.

6. Dante is so wounded by Beatrice’s venomous reference to his “beard” that he finds it harder to look up at her than it would be for the wind to uproot an oak tree. And yet, Dante is that oak tree, having been “uprooted” from his past sins by the “winds” of Beatrice’s prosecution. Robert Hollander notes here an interesting comparison between Dante and Virgil’s portrayal of Aeneas as an oak tree in the Aeneid (IV:441ff): “Aeneas is compared to a deeply rooted oak tree buffeted by north winds when Dido makes he r last-ditch appeal to him to stay with her in Carthage. In the end, he remains strong enough in his new resolve to deny her request and set sail. Here, the ‘new Aeneas,’ buffeted by the south wind, gives over his stubborn recalcitrance and accedes to the insistent demand of Beatrice, a new and better Dido, that he express his contrition. Where it was good for Aeneas to resist the entreaties of his woman, it is also good for Dante to yield to Beatrice’s.”

Still hurting, when he does “raise his beard,” he lacks the courage to look directly at Beatrice and focuses on the angels instead. And adding an interesting detail here, he notices that the angels’ rain of flowers has stopped. As we continue reading, it will soon become apparent that this seemingly small detail marks the end of Dante’s prosecution and the next stage of his redemption. Recall that when Beatrice first appeared, she was wearing a white veil and that she was additionally veiled by the rain of flowers, which has now been removed.

7. Dante notes that the griffin is a single creature, but with two natures. We know that it is a mythical creature with the body of a lion and the head of an eagle. And it was noted earlier that this particular griffin also has two great wings that reach up in to the sky. It’s head is gold, and its body is white with red markings. Most importantly, this griffin represents Christ in his two natures as God and human.

But a marvelous transformation now occurs as the white-veiled Beatrice faces the griffin-Christ. Beautiful as she already was in life, Dante explains that at this moment she surpasses any other notion of beauty. Mark Musa notes here that in the Vita Nuova , the Poet wrote that “she was more than a woman. She was one of the most beautiful of the angels in Heaven.” Seeing this vision, he comes to the final necessary realization that seals his penitence and begins their long-awaited reunion. In a last burst of remorse, seeing everything that led him astray, all the things he had substituted for her, these, he tells us, he now hated the most.

8. Twice before, Dante, overcome by emotion, has fainted (see Inf. 3 and 5). This third time climaxes his confession. When he revives, he realizes that he is being led through the waters of the Lethe by Matelda, the mysterious young woman he encountered soon after he entered the Earthly Paradise. Gently and tenderly she guides him through the deep waters, reassuring him as Virgil did earlier when they passed through the wall of flames. Her movement across the water is reminiscent of Jesus’s walking on the water. The water of this stream not only cleanses him after his confession (a symbolic baptism), it also removes all memory of sin (see Aeneid VI:715). Mark Musa notes here: “The waters of Lethe wash away the memory of sin on the emotional plane. Beatrice excises Dante’s sin with the sword of her words; Lethe heals the wound. Memory of pain and sadness is covered over and what remains is an unbroken, whole spirit, capable of speaking of sin objectively rather than subjectively.”

The waters here also remind us of an earlier cleansing at the foot of the mountain when Cato sent the two Pilgrims to the shore and told Virgil to wash the grime of Hell off Dante’s face. And they are also a remembrance of Dante’s baptism which not only cleansed him from sin, but initiated him into the Christian community. And here in Lethe, he is both cleansed and initiated into the community of Paradise which he will soon enter.

9. Asperges me, Latin, "You will sprinkle me".

As Dante is being led through the waters of Lethe by Matelda, he hears the singing of Psalm 51 (vv.3-19). Perhaps the angels are still present to sing this final hymn. This Psalm is often sung or recited at the beginning of the Liturgy as the priest walks u p and down the aisles of the church sprinkling the congregation with holy water as a symbol of their purification. This is what Dante heard as he passed through the Lethe:

“Have mercy on me, God, in accord with your merciful love; in your abundant compassion blot out my transgressions.

Thoroughly wash away my guilt; and from my sin cleanse me. For I know my transgressions; my sin is always before me.

Against you, you alone have I sinned; I have done what is evil in your eyes. So that you are just in your word, and without reproach in your judgment.

Behold, I was born in guilt, in sin my mother conceived me.

Behold, you desire true sincerity; and secretly you teach me wisdom.

Cleanse me with hyssop, that I may be pure; wash me, and I will be whiter than snow.

You will let me hear gladness and joy; the bones you have crushed will rejoice.

Turn away your face from my sins; blot out all my iniquities.

A clean heart create for me, God; renew within me a steadfast spirit.

Do not drive me from before your face, nor take from me your holy spirit.

Restore to me the gladness of your salvation; uphold me with a willing spirit.

I will teach the wicked your ways, that sinners may return to you.

Rescue me from violent bloodshed, God, my saving God, and my tongue will sing joyfully of your justice.

Lord, you will open my lips; and my mouth will proclaim your praise.

For you do not desire sacrifice or I would give it; a burnt offering you would not accept.

My sacrifice, O God, is a contrite spirit; a contrite, humbled heart, O God, you will not scorn.”

10. We now move to another ritual. Dante is taken from the waters of the Lethe to stand along the left side of the chariot where the four women representing the Cardinal Virtues (prudence, justice, fortitude, and temperance) sing and dance around Dante before t hey present him to Beatrice. They, like the angel choir, are still present for one final duty. As forest nymphs in the Earthly Paradise, as stars in the heavens, and as foreordained handmaidens of Beatrice, these four women will bring Dante in front of the griffin where he and Beatrice will be able to look at each other. Noting their secondary status as natural virtues, they tell Dante that the three women on the chariot’s right side (the Theological Virtues of Faith, Hope, and Love) will clear his sight so t hat he will be able to see the true beauty of Beatrice’s face.

About these Natural or Cardinal Virtues, Robert Hollander thinks of them as representing the active life (recall Leah earlier), and makes an interesting point that highlights a significant difference between poetry and prose: “The stars they are in heaven a re probably identical with those we saw in Purgatorio 1:23, irradiating the face of Cato with their light. Dante thus seems to suggest that both Cato and Beatrice are of such special virtue that it seems that original sin did not affect them-–a notion that could only be advanced in the sort of suggestive logic possible in poetry, for it is simply heretical. Dante never did say such a thing in prose.”

In the end, we must remember that Dante wrote the Vita Nuova about Beatrice, and as Charles Singleton, notes in his commentary: “Beatrice here at the top of the Mountain of Purgatory is always the Beatrice of the Vita Nuova, in which … she is declared t o be the”queen of the virtues” (VN X:2), and “a thing come from heaven to earth, to show forth a miracle” (VN XXVI: 6).

11. Beatrice and Dante stand facing each other with the griffin between them. She is at the front of the chariot, he standing in front of the griffin. Apparently, Beatrice has lowered her white veil just enough to uncover her eyes, and prompted by the four Cardinal Virtues, Dante looks into those emerald eyes (the color of hope). At this moment a great revelation takes place. To explain his excitement at what he sees, he says: “A thousand flames of desire held my gaze upon those shining eyes.” Dante the Poet tell s us that as Beatrice looked at the griffin, its two natures were reflected in her eyes, not as lion and eagle, but as Christ God and Christ human in one and the same being. Her eyes are like two mirrors reflecting the sun, which is an image of God.

12. Using the image of the mirrors from another point of view, for Dante, seeing an object in a mirror (in this case, the two natures of Christ) is not the same as seeing the object face-on. The words of St. Paul in his First Letter to the Corinthians (13:12) come to mind here: “Now we see as in a mirror, but then face to face.” Dante is still in the “now” part. Beatrice sees God face to face. He sees the two natures alternately. Beatrice sees them at the same time. “Can you imagine my amazement?” he asks the reader. And in doing so, draws us into the revelation he has just experienced.

13. Awestruck at the revelatory experience he has just had, Dante expresses his joy in words taken from the Book of Sirach (24:21): “Those who eat of me will hunger still, those who drink of me will thirst for more.” This is an image of the Eucharist (Christ, Beatrice) and a foretaste of the heavenly banquet. Allegorically, it represents Wisdom and Truth. These images of eating and drinking all require the mouth, and this leads to Beatrice’s next unveiling.

14. “The three theological virtues sing their appeal to Beatrice, requesting that she unveil her mouth. The moment recalls an experience recorded in the Convivio: ‘Here it is necessary to know that the eyes of wisdom are her demonstrations, by which truth is seen with the greatest certainty, and her smiles are her persuasions, in which the inner light of wisdom is revealed behind a kind of veil; and in each of them is felt the highest joy of blessedness, which is the greatest good of paradise. This joy cannot b e found in anything here below except by looking into her eyes and upon her smile.” It is important to know that these words are directed to another lady, also known as Wisdom in the Convivio, namely the Lady Philosophy, the one who came as the replacement for the then supposedly less worthy Beatrice.”

15. Mount Parnassus is a mountain range of Central Greece that is, and historically has been, especially valuable to the Greek nation and the earlier Greek city-states for many reasons. The mountain is the location of historical, archaeological, and other cultural sites, such as Delphi perched on the southern slopes of the mountain in a rift valley north of the Gulf of Corinth.

Top of page