Dante's Divine Comedy: Purgatorio

Canto XIII

Dante and Virgil reach the Second Cornice, where the sin of Envy is being purged, to find it deserted. Virgil looks up at the sun for guidance. The poets suddenly hear voices in the air (the Whip of Envy), crying out Christian and pagan examples of Generosity, the opposing virtue. They see the penitent Envious sitting down, dressed in sackcloth, their eyelids sewn shut as they implore the charity of the saints. Dante talks to the spirit of Sapia Bigozzi of Siena, who rejoiced when her countrymen suffered defeat at the battle of Colle against the Florentines.

We were upon the summit of the stairs,

Where for the second time is cut away

The mountain, which ascending shriveth all.

There in like manner doth a cornice bind

The hill all round about, as does the first,

Save that its arc more suddenly is curved.

Shade is there none, nor sculpture that appears;

So seems the bank, and so the road seems smooth,

With but the livid color of the stone.

"If to inquire we wait for people here,"

The Poet said, "I fear that peradventure

Too much delay will our election have."

Then steadfast on the sun his eyes he fixed,

Made his right side the center of his motion,

And turned the left part of himself about.

"O thou sweet light! with trust in whom I enter

Upon this novel journey, do thou lead us,"

Said he, "as one within here should be led.

Thou warmest the world, thou shinest over it;

If other reason prompt not otherwise,

Thy rays should evermore our leaders be!"

As much as here is counted for a mile,

So much already there had we advanced

In little time, by dint of ready will;

And tow'rds us there were heard to fly, albeit

They were not visible, spirits uttering

Unto Love's table courteous invitations,[1]

The first voice that passed onward in its flight,

"Vinum non habent," said in accents loud,

And went reiterating it behind us.[2]

And ere it wholly grew inaudible

Because of distance, passed another, crying,

"I am Orestes!" and it also stayed not.[3]

"O," said I, "Father, these, what voices are they?"

And even as I asked, behold the third,

Saying: "Love those from whom ye have had evil!"

And the good Master said: "This circle scourges

The sin of envy, and on that account

Are drawn from love the lashes of the scourge.[4]

The bridle of another sound shall be;

I think that thou wilt hear it, as I judge,

Before thou comest to the Pass of Pardon.

But fix thine eyes athwart the air right steadfast,

And people thou wilt see before us sitting,

And each one close against the cliff is seated."

Then wider than at first mine eyes I opened;

I looked before me, and saw shades with mantles

Not from the color of the stone diverse.[5]

And when we were a little farther onward,

I heard a cry of, "Mary, pray for us!"

A cry of, "Michael, Peter, and all Saints!"[6]

I do not think there walketh still on Earth

A man so hard, that he would not be pierced

With pity at what afterward I saw.

For when I had approached so near to them

That manifest to me their acts became,

Drained was I at the eyes by heavy grief.

Covered with sackcloth vile they seemed to me,

And one sustained the other with his shoulder,

And all of them were by the bank sustained.[7]

Thus do the blind, in want of livelihood,

Stand at the doors of churches asking alms,

And one upon another leans his head,

So that in others pity soon may rise,

Not only at the accent of their words,

But at their aspect, which no less implores.

And as unto the blind the sun comes not,

So to the shades, of whom just now I spake,

Heaven's light will not be bounteous of itself;

For all their lids an iron wire transpierces,

And sews them up, as to a sparhawk wild

Is done, because it will not quiet stay.[8]

To me it seemed, in passing, to do outrage,

Seeing the others without being seen;

Wherefore I turned me to my counsel sage.

Well knew he what the mute one wished to say,

And therefore waited not for my demand,

But said: "Speak, and be brief, and to the point."

I had Virgilius upon that side

Of the embankment from which one may fall,

Since by no border 'tis engarlanded;

Upon the other side of me I had

The shades devout, who through the horrible seam

Pressed out the tears so that they bathed their cheeks.

To them I turned me, and, "O people, certain,"

Began I, "of beholding the high light,

Which your desire has solely in its care,

So may grace speedily dissolve the scum

Upon your consciences, that limpidly

Through them descend the river of the mind,

Tell me, for dear 'twill be to me and gracious,

If any soul among you here is Latian,

And 'twill perchance be good for him I learn it."

"O brother mine, each one is citizen

Of one true city; but thy meaning is,

Who may have lived in Italy a pilgrim."

By way of answer this I seemed to hear

A little farther on than where I stood,

Whereat I made myself still nearer heard.

Among the rest I saw a shade that waited

In aspect, and should any one ask how,

Its chin it lifted upward like a blind man.

"Spirit," I said, "who stoopest to ascend,

If thou art he who did reply to me,

Make thyself known to me by place or name."

"Sienese was I," it replied, "and with

The others here recleanse my guilty life,

Weeping to Him to lend himself to us.[9]

Sapient I was not, although I Sapia

Was called, and I was at another's harm

More happy far than at my own good fortune.

And that thou mayst not think that I deceive thee,

Hear if I was as foolish as I tell thee.

The arc already of my years descending,

My fellow-citizens near unto Colle

Were joined in battle with their adversaries,

And I was praying God for what he willed.

Routed were they, and turned into the bitter

Passes of flight, and I, the chase beholding,

A joy received unequaled by all others;

So that I lifted upward my bold face

Crying to God, 'Henceforth I fear thee not,'

As did the blackbird at the little sunshine.

Peace I desired with God at the extreme

Of my existence, and as yet would not

My debt have been by penitence discharged,

Had it not been that in remembrance held me

Pier Pettignano in his holy prayers,

Who out of charity was grieved for me.[10]

But who art thou, that into our conditions

Questioning goest, and hast thine eyes unbound

As I believe, and breathing dost discourse?"

"Mine eyes," I said, "will yet be here ta'en from me,

But for short space; for small is the offense

Committed by their being turned with envy.

Far greater is the fear, wherein suspended

My soul is, of the torment underneath,

For even now the load down there weighs on me."

And she to me: "Who led thee, then, among us

Up here, if to return below thou thinkest?"

And I: "He who is with me, and speaks not;

And living am I; therefore ask of me,

Spirit elect, if thou wouldst have me move

O'er yonder yet my mortal feet for thee."

"O, this is such a novel thing to hear,"

She answered, "that great sign it is God loves thee;

Therefore with prayer of thine sometimes assist me.

And I implore, by what thou most desirest,

If e'er thou treadest the soil of Tuscany,

Well with my kindred reinstate my fame.

Them wilt thou see among that people vain

Who hope in Talamone, and will lose there

More hope than in discovering the Diana;[11]

But there still more the admirals will lose."

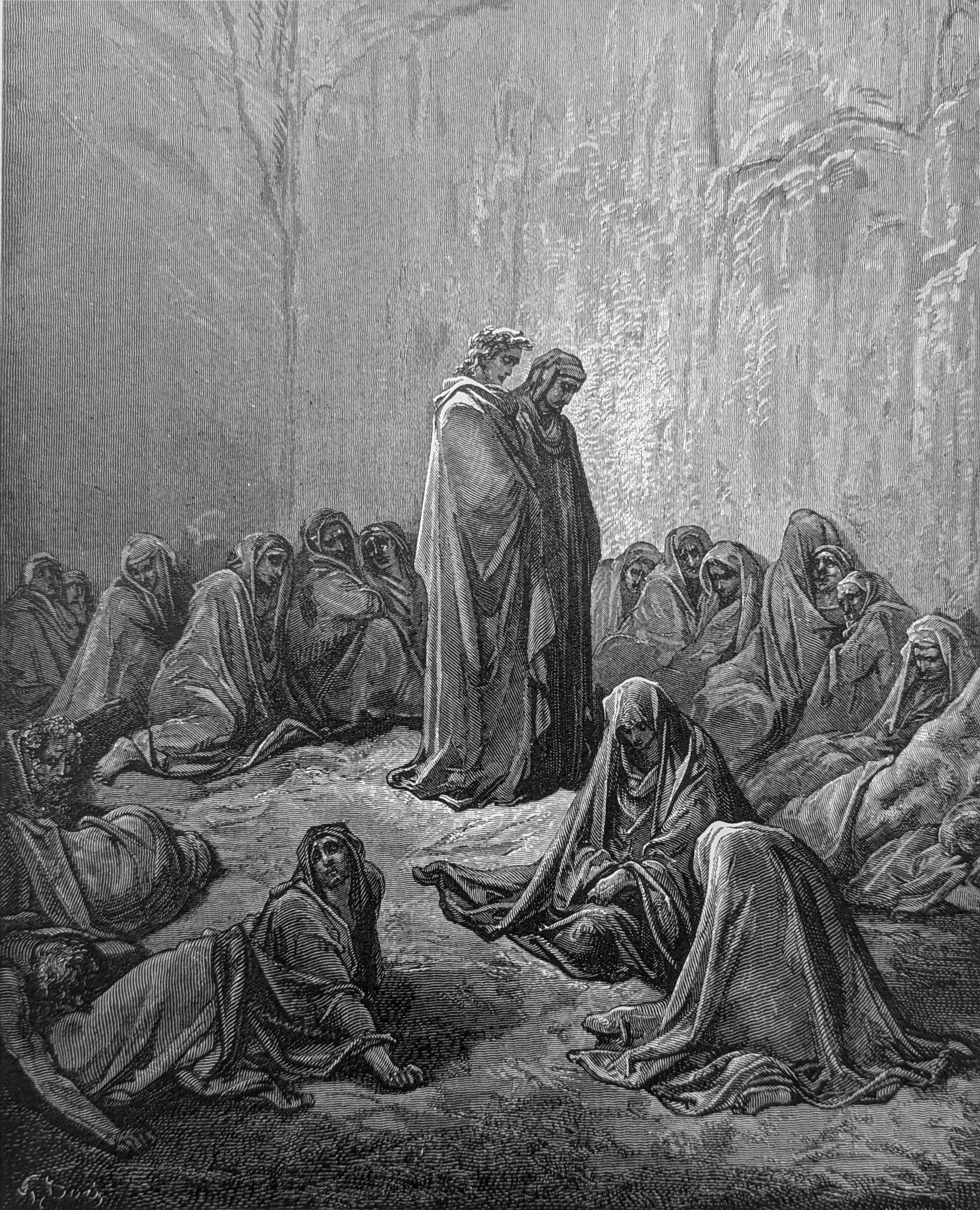

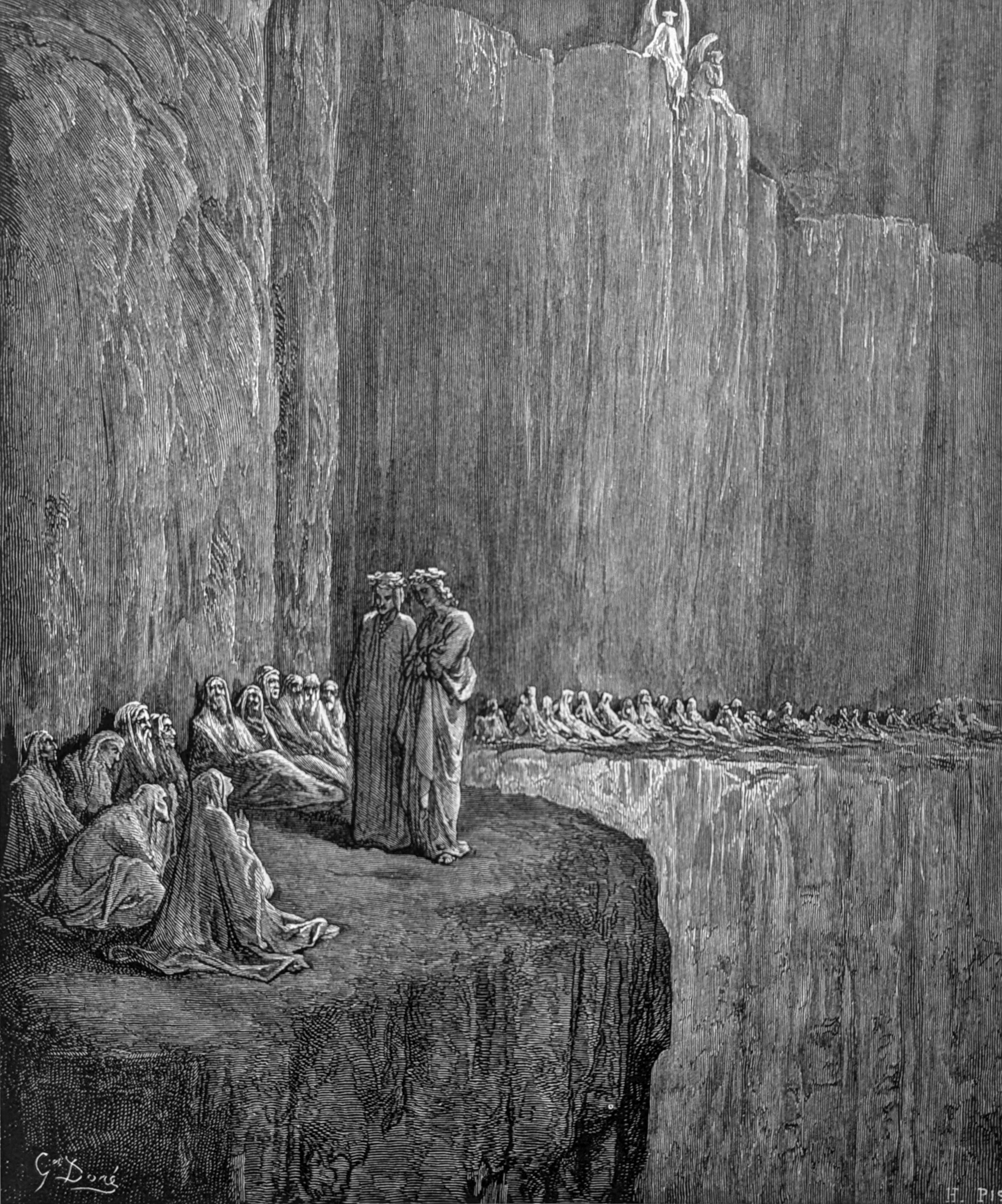

Illustrations of Purgatorio

Covered with sackcloth vile they seemed to me, / And one sustained the other with his shoulder,/ And all of them were by the bank sustained. Purg. XIII, lines 58-60

"Sienese was I," it replied, "and with / The others here recleanse my guilty life", Purg. XIII, lines 106-107

Footnotes

1. These invisible exhortations act as continual reminders of the invitation of Christ. In John 6:51 we read: “I am the living bread that came down from heaven; whoever eats this bread will live forever; and the bread that I will give is my flesh for the life of the world.” Furthermore, the Church teaches that, in addition to the Sacraments of Reconciliation (Confession) and Anointing of the Sick, the Eucharist is also a sacrament of healing that cleanses us from sin (Catechism of the Catholic Faith, 1394).

2. “Vinum non habent”: “They have no wine.” First of all, a reminder that part of the structure of the seven terraces is that the first whip is always an event that involves Jesus’ mother, Mary. So we recall from the terrace below that the first of the great carvings on the wall was a scene of the Annunciation. The scene evoked here is from the Gospel of St. John and the Wedding Feast at Cana in Galilee (2:1-10). Jesus and his mother are at a wedding party and the wine runs out. Mary quietly brings this to Jesus ’ attention and he changes the water into wine. It is the Virgin Mary’s loving charity and concern for their happiness that saves the hosts from embarrassment, and this is the example for the sinners here.

3. “I am Orestes”: As the first voice flies past the Pilgrims and trails off, they hear another one. This one evokes a story of a great friendship where the friends are willing to die that the other might live. Dante probably came across this story in Cicero’s De amicitia (VII, 24) or his De finibus (V, xxii, 63). It’s the story of Orestes (son of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra) and his friend Pylades and their exchange of identities. (There are variants of this story in Greek literature.) Orestes killed his mot her to avenge the death of his father, whom she murdered. He was condemned to death, but Pylades claimed that he was Orestes. But Orestes could not allow his friend to make such a sacrifice and came forward with his true identity. Although this is a story f rom pagan literature, Dante most likely has in mind the statement of Jesus in St. John’s Gospel (15:12f): “My commandment is this: love one another as I love you. No one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends.” The whip is clear. For the envious, the ultimate act of virtue would be to die for a friend, to give up what one holds most dear.

4. And only now does Virgil reveal that this terrace is where the sin of envy is purged–but with a whip made from cords of love. And at the same time, he informs his pupil that they will hear opposite statements (the rein of envy) just before they leave this terrace.

5. We still do not know exactly what the punishment of the envious sinners is, and Dante is clever to build anticipation of that knowledge by slowly adding details as he perceives them himself. If we consider how visual and engaging the carvings were on the previous terrace, the contrast between these two terraces becomes clear with Dante’s straining to see the envious sinners. Everything here is of the same color and nothing really stands out. Virgil himself seems to have just caught sight of the sinners as he points out where they are. Recall that everything on this terrace is a livid color: the ground, the wall of the mountainside, and the sinners’ clothing. This is clever on the poet’s part because the envious here blend into their surroundings and there’s no distinction between them. In life, distinctions were important to them. Even their features seem to be blurred or muted–quite a contrast to the brilliant carvings on the terrace below.

6. As the two get closer, Dante hears the envious praying the long and beautiful Litany of the Saints (Dante gives only a few lines here). Even though these were, to varying degrees, grave sinners, here they pray to the Saints for help. In Hell, they would be shrieking curses. The fact that they pray is both evidence of and a sign of their spiritual progress. And, of course, those to whom they pray were not tainted by the sin of envy. Again, notice that Mary is the first Saint invoked. We observed earlier how orderly and harmonious was the singing in Purgatory. Note how the Litany here is inclusive as was the Lord’s Prayer at the beginning of Canto 10. The sinners pray “for us,” not “for me.”

7. Remarking on Dante’s observation about the “coarse sackcloth,” John Ciardi offers a realistic, and somewhat humorous, image of what is worn by the sinners which, in itself, must have been quite punishing:

“Even today peasants wear haircloth capes in heavy weather, but in the Middle Ages, and beyond, haircloth was worn against the skin as a penance, and to discipline the flesh. Such hair shirts were not only intolerably itchy; they actually rubbed the flesh o pen causing running sores. In an age, moreover, that was very slightly given to soap and water, such hair shirts offered an attractive habitat to all sorts of bodily vermin that were certain to increase the odor of sanctity, even to the point of the gangrenous. I am told, and have no wish to verify, that hair shirts are still worn today by some penitential and unventilated souls.”

8. In the Middle Ages, falconry (the use of birds of prey to hunt small animals) was a sport with ancient roots almost exclusive to royalty and the aristocracy. While there were other ways of taming and training the birds, what Dante refers to involves a baby falcon, hawk, or other bird of prey taken as a chick. A thread of delicate waxed silk was sown through its lower eyelids (apparently painless) and drawn back over the bird’s head and tied. During training, the thread was gradually loosened allowing the bird to see more and more until it was used to its trainer/handler. Then it was removed altogether. Dante makes this worse by substituting iron thread instead of silk. But like the falcons, however, these envious souls are being “trained” by the invisible voice s, by their prayers, and by their beggar-like camaraderie. And because envy is a sin of the eyes, their blindness weans them away from seeing what others have that they want. It also forces them to look inward and focus on what is necessary for their purgation. Furthermore, blindness makes one vulnerable to so many things the sighted can avoid. Yet, while no harm will come to them here, they are somehow rendered “vulnerable” to the good that comes by way of their introspection and the prayers of others.

9. One suspects that the Pilgrim got more than he bargained for when this soul responds to his query. It elicits a chatty, transparent, confessional response that comes from a Sienese woman who seems well along the path to purification. Like the other envious souls here, she “mends” her soul with tears–-a clever reminder that her eyes are sewn shut. Dante’s mention of her “discipline” is also a reminder that in Purgatory the souls willingly purge themselves.

Sapia was from an important Sienese family, the Salvani. She was married to Ghinaldo Saracini and was the aunt of Provenzan Salvani, the great tyrant of Siena whom Oderisi spoke about in Canto 11. Her candor is refreshing as she plays on the Latin root of h er name (sapiens = wisdom), suggesting that she wasn’t too smart during her lifetime, and her unabashed confession is breath-taking. We haven’t quite met a sinner like her who gives the details of her sins so strikingly. On the other hand, she knows that she’s saved and a detailed account of her treasonous envy will do her no harm. Ironically, in this place it’s actually rather good for her!

She loved nothing more than seeing others come to grief. Thinking, perhaps, that her candor is too much for Dante to believe, she offers a striking example. In 1269 (Dante would have been 4 years old) the Sienese Ghibellines fought the Florentine Guelphs at Colle (about 20 miles northwest of Siena). Siena lost the battle, and Sapia who, apparently, had no love for the Sienese, rejoiced when she saw her townsmen fleeing the battlefield in defeat. She actually prayed that they would lose! And then, looking up t o Heaven, shouted to God that she no longer feared Him! We haven’t heard something like this since we encountered the blasphemous Capaneus in the 14th Canto of the Inferno, or the thief Vanni Fucci in the 25th Canto of the same. (Sayers suggests that she ma y have been banished from Siena and held a grudge, and that she was living in Colle and watched the battle from a tower.) Recall that her uncle, Provenzan, had been captured and beheaded during that battle, his head paraded around at the end of a pike! It may be, as Hollander suggests in his commentary: “Since her sin was envy, it seems clear that Dante wants us to understand that she resented his and/or other townsmen’s position and fame, that her involvement was personal, not political.” Furthermore, as she will say, she was like this until she was old. She grew old in this sin.

As for the foolish blackbird, Sapia was probably quoting a fable about the blackbird who, after a few days of mid-winter sunshine, foolishly thought spring had come and began to sing. The fact that she quotes this adage in reference to herself, however, shows that she is now humble enough to recognize the folly of her sin.

10. One might wonder at this point why Sapia is not in Hell. Though she repented at the end of her life, and even left a bequest in her will to support a local hospice for pilgrims, she realizes now that it might not have been enough to save her-–had it not bee n for Pier Pettinaio who prayed for her after she died. For all practical purposes, she should be in Ante-Purgatory, and surely she spent some time on the Terrace of Pride before coming to this one.

Early in his life, Pier Pettinaio (1189-1289) was a Sienese comb-seller (Pettinaio was not his family name, but his occupation. Pettine = comb). He was noted for his honesty and humility and later became a Franciscan monk, famous as a mystic and holy man who cared for the poor and the sick and worked many miracles among them. He was highly revered as a saint by the Sienese, who built a lovely tomb for him when he died. He was beatified in 1802.

11. It seems that Sapia’s family were among the advocates of a Sienese public works project that would build a port for the Republic of Siena at the western city of Talamone on the Tyrrhenian Sea. This project would have greatly enhanced the economic prospects of the republic, which did not have a port, but it turned out to be more of a headache than a boon. Sapia’s request was most likely aimed at Dante steering her relatives away from such useless and foolish schemes. In a witty introduction to his commentary h ere, John Ciardi notes that this is “a complicated passage of local reference certainly put into Sapia’s mouth by Dante as a Florentine jibe at the ‘foolish’ Sienese. Dante (who fears the Ledge of Pride just below him) may have to carry his stone a bit further for his addiction to such touches, but his poem is certainly the livelier for them.”

As it turns out, the Sienese wanted to compete with the seafaring Republic of Genoa, and in 1303 they chose Talamone (about 80 miles south of Siena) as the place for their new port. In spite of considerable outlay for construction, the port might have become a reality except for the fact that, among other things, it was located in the area of a malarial swamp (the Maremma), and it kept silting up. The project was a fiasco like the other one Sapia mentions, the attempt to increase Siena's water supply by digging for an underground river they named after the statue of Diana in the city’s marketplace. (Both projects came about as a result of an over-weaning civic pride, both ended on the rocks!)