Dante's Divine Comedy: Purgatorio

Canto XXIII

Near the tree, the three poets hear Labia Mea, Domine before being overtaken by a group of former Gluttons, now starved spirits. Dante recognizes Forese Donati, his former boon companion, by his voice as the wasted face is unfamiliar to him. The pilgrim expresses great surprise at not seeing his friend detained in Ante-Purgatory among the Indolent—after all, he was a late repentant and recently deceased. Forese admits his purgation has been greatly accelerated by bis devoted wife Nella's incessant prayers and attacks contemporary Florentine women for their extravagance. Dante explains the reason for his journey.

The while among the verdant leaves mine eyes

I riveted, as he is wont to do

Who wastes his life pursuing little birds,[1]

My more than Father said unto me: "Son,

Come now; because the time that is ordained us

More usefully should be apportioned out."

I turned my face and no less soon my steps

Unto the Sages, who were speaking so

They made the going of no cost to me;

And lo! were heard a song and a lament,

"Labia mea, Domine," in fashion

Such that delight and dolence it brought forth.[2]

"O my sweet Father, what is this I hear?"

Began I; and he answered: "Shades that go

Perhaps the knot unloosing of their debt."

In the same way that thoughtful pilgrims do,

Who, unknown people on the road o'ertaking,

Turn themselves round to them, and do not stop,

Even thus, behind us with a swifter motion

Coming and passing onward, gazed upon us

A crowd of spirits silent and devout.

Each in his eyes was dark and cavernous,

Pallid in face, and so emaciate

That from the bones the skin did shape itself.

I do not think that so to merest rind

Could Erisichthon have been withered up

By famine, when most fear he had of it.[3]

Thinking within myself I said: "Behold,

This is the folk who lost Jerusalem,

When Mary made a prey of her own son."

Their sockets were like rings without the gems;

Whoever in the face of men reads 'omo'

Might well in these have recognized the 'm.'[4]

Who would believe the odor of an apple,

Begetting longing, could consume them so,

And that of water, without knowing how?

I still was wondering what so famished them,

For the occasion not yet manifest

Of their emaciation and sad squalor;

And lo! from out the hollow of his head

His eyes a shade turned on me, and looked keenly;

Then cried aloud: "What grace to me is this?"

Never should I have known him by his look;

But in his voice was evident to me

That which his aspect had suppressed within it.

This spark within me wholly re-enkindled

My recognition of his altered face,

And I recalled the features of Forese.[5]

"Ah, do not look at this dry leprosy,"

Entreated he, "which doth my skin discolor,

Nor at default of flesh that I may have;

But tell me truth of thee, and who are those

Two souls, that yonder make for thee an escort;

Do not delay in speaking unto me."

"That face of thine, which dead I once bewept,

Gives me for weeping now no lesser grief,"

I answered him, "beholding it so changed!

But tell me, for God's sake, what thus denudes you?

Make me not speak while I am marveling,

For ill speaks he who's full of other longings."

And he to me: "From the eternal council

Falls power into the water and the tree

Behind us left, whereby I grow so thin.[6]

All of this people who lamenting sing,

For following beyond measure appetite

In hunger and thirst are here re-sanctified.

Desire to eat and drink enkindles in us

The scent that issues from the apple-tree,

And from the spray that sprinkles o'er the verdure;

And not a single time alone, this ground

Encompassing, is refreshed our pain,--

I say our pain, and ought to say our solace,--

For the same wish doth lead us to the tree

Which led the Christ rejoicing to say 'Eli,'

When with his veins he liberated us."[7]

And I to him: "Forese, from that day

When for a better life thou changedst worlds,

Up to this time five years have not rolled round.

If sooner were the power exhausted in thee

Of sinning more, than thee the hour surprised

Of that good sorrow which to God reweds us,

How hast thou come up hitherward already?

I thought to find thee down there underneath,

Where time for time doth restitution make."

And he to me: "Thus speedily has led me

To drink of the sweet wormwood of these torments,

My Nella with her overflowing tears;[8]

She with her prayers devout and with her sighs

Has drawn me from the coast where one awaits,

And from the other circles set me free.

So much more dear and pleasing is to God

My little widow, whom so much I loved,

As in good works she is the more alone;

For the Barbagia of Sardinia

By far more modest in its women is

Than the Barbagia I have left her in.

O brother sweet, what wilt thou have me say?

A future time is in my sight already,

To which this hour will not be very old,

When from the pulpit shall be interdicted

To the unblushing womankind of Florence

To go about displaying breast and paps.

What savages were e'er, what Saracens,

Who stood in need, to make them covered go,

Of spiritual or other discipline?[9]

But if the shameless women were assured

Of what swift Heaven prepares for them, already

Wide open would they have their mouths to howl;

For if my foresight here deceive me not,

They shall be sad ere he has bearded cheeks

Who now is hushed to sleep with lullaby.

O brother, now no longer hide thee from me;

See that not only I, but all these people

Are gazing there, where thou dost veil the sun."

Whence I to him: "If thou bring back to mind

What thou with me hast been and I with thee,

The present memory will be grievous still.

Out of that life he turned me back who goes

In front of me, two days agone when round

The sister of him yonder showed herself,"[10]

And to the sun I pointed. "Through the deep

Night of the truly dead has this one led me,

With this true flesh, that follows after him.

Thence his encouragements have led me up,

Ascending and still circling round the mount

That you doth straighten, whom the world made crooked.

He says that he will bear me company,

Till I shall be where Beatrice will be;

There it behooves me to remain without him.

This is Virgilius, who thus says to me,"

And him I pointed at; "the other is

That shade for whom just now shook every slope

Your realm, that from itself discharges him."

Illustrations of Purgatorio

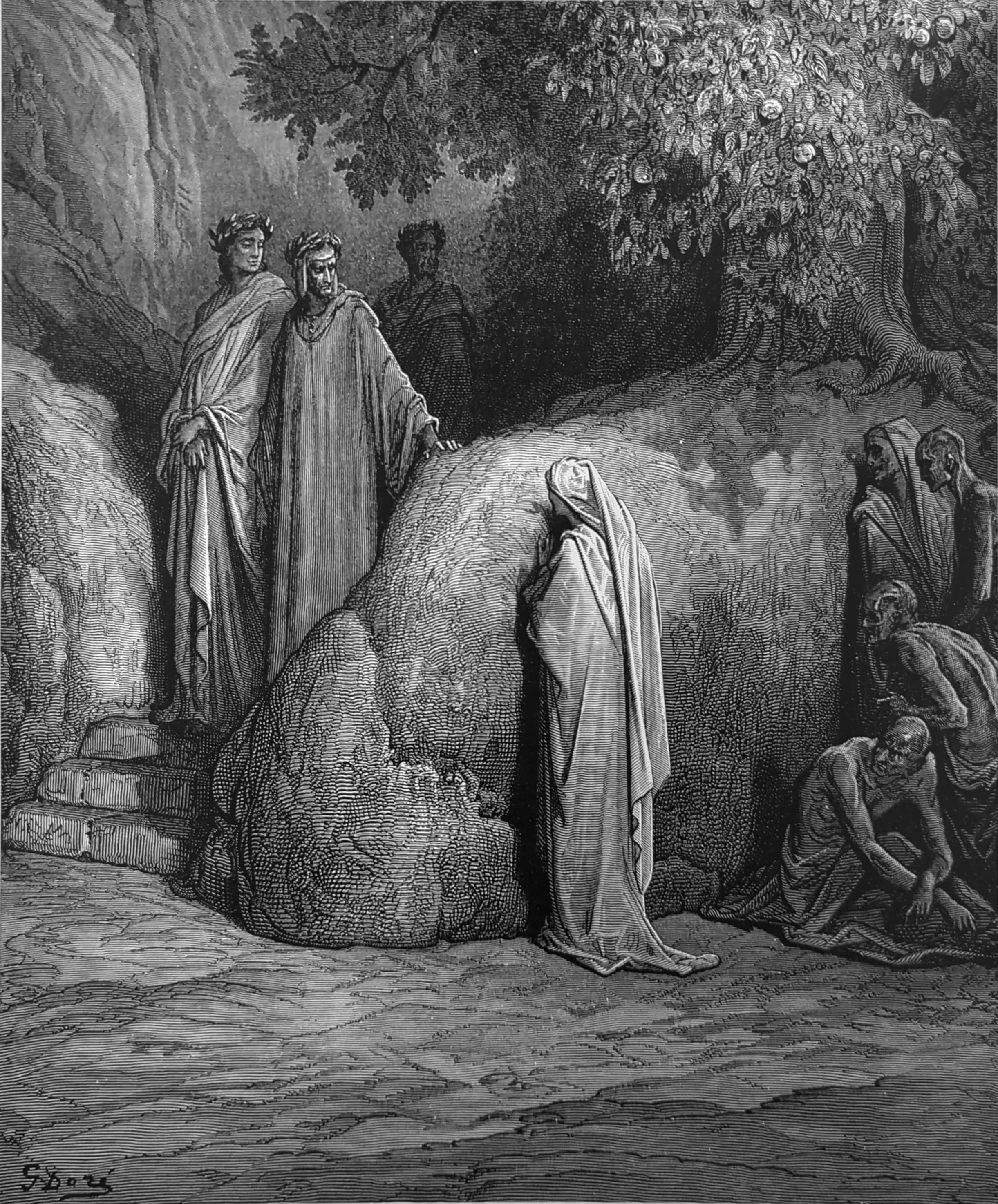

"Ah, do not look at this dry leprosy," / Entreated he, "which doth my skin discolour, / Nor at default of flesh that I may have;" Purg. XXIII, lines 49-51

Footnotes

1. Though bird-hunting was popular in the Middle Ages (as it still is in many places), Dante probably considered this to be a waste of time. And Virgil’s reference to the short time left for their journey seems to amplify this and moves Dante away from this momentary distraction. Interestingly enough, there’s no overt sense here that Dante would rather have discovered who it was who spoke the warning–-an angel, perhaps?–-though that’s most likely why he stopped to look in the first place. That Virgil refers to D ante as “my son” is a tenderness that highlights again the deeper significance of their relationship in light of their shared pilgrimage. In his commentary at this point, Robert Hollander reminds us that this “may also reflect the Roman poet’s extraordinary ability to bring a pagan–-and perhaps even this backsliding Christian–-to Christ, as Statius’ narrative (in the previous canto) has established.”

2. Moving again along the Terrace of Gluttony, Dante enjoys following the two poets whose conversation makes their walking even easier, until it is interrupted by the sad chanting of the first part of verse 17 from Psalm 51: “Lord, open my lips.” Dante tells u s that, hearing this verse, they were filled “with feelings of both joy and regret.” The whole line reads: “Lord, open my lips, and my mouth will be filled with praise.” This is a fitting prayer for the gluttons, who in life often filled their mouths to excess with rich food and drink, and who now ask for the food of praise. More than that, these souls yearn for “the bread of angels,” that rich image of the Eucharist, the heavenly food on which they will feast when their penitence is completed.

3. Erysichthon was a Thessalian prince who wanted to construct a feasting hall adjacent to his palace. Violating a grove of trees sacred to the goddess Ceres, he ignored her warnings and cut down the trees. She punished him with such an all-consuming hunger that he spent his fortune and goods on food that only made him hungrier. In the end, he engorged himself with his own flesh and died.

The sinners Dante describes here would most likely be on the verge of death were they still alive in our world. One is reminded of photos of concentration camp inmates starved almost beyond human recognition. The sinners here are like walking skeletons, their skin virtually transparent on their bones–-quite the opposite, most likely, of their portly bodies when they were alive. Their eyes, complicit with their sin when they were alive, are sunk so far back into their heads they are hardly visible. If the eyes are the windows of the soul, these souls are well-hidden by their sin.

4. Returning to the sinners’ eyes–their sockets, actually–-Dante makes a clever visualization. First, the sockets of these sinners’ eyes look like rings that have lost their stones, making them, in large part, worthless. But then he goes in an entirely different direction by suggesting that he could “see” the Italian/Latin word, omo (man) in the gluttons’ skull-like faces: the m being the nose and forehead, as it were, and the o on either side being the eyes. Strange as this might seem to us, devout medievals saw the words omo dei (Man of God) printed on the human face. Dorothy Sayers offers this explanation in her commentary: “According to a pious medieval conceit, the words “[H]OMO DEI” (man [is] of God) were plainly written in the human countenance, the eyes re presenting the two O’s, the line of the cheeks, eyebrows, and nose forming a script M, while the D, E, I are shown in the ears, nostrils, and mouth. On these wasted faces the bony outline of the M stood out with startling clearness.” The significance here, of course, is that each of us is imprinted with the image of God, the imago dei (see Genesis 1:26). Sin distorts that image spiritually, and in this case, gluttony distorts it physically. And Dante takes this one step further with his imagery of the terrible emaciation of these repenting gluttons.

5. The extent of this sinner’s disfigurement rendered Dante blind, in a sense, and it is the gracious voice of his dear friend, Forese Donati, that now enables the Pilgrim truly to “see” who he has been staring at. His unchanged voice from the past “sparks” their close relationship back into flames, and initiates one of the longest conversations in the entire Poem–-from here to the end of this canto and 100 lines into the next.

Forese Donati was born in Florence around 1260 and died there in 1295. His family was ancient and noble, and Dante’s wife, Gemma, was a cousin of his. Born five years before Dante and nicknamed Bicci Novello, the two men were lifelong friends and poets. Som e of the humorous, sometimes insulting, sonnets they sent back and forth to each other still exist, and it might be inferred that their friendship had its wild side when they were younger. We will meet his sainted sister, Piccarda, in the Paradiso, and their older brother, Corso, hated by many in Florence, may well be in Hell for his evil deeds. Forese will speak about his siblings in the next canto.

6. Forese begins to satisfy Dante’s curiosity by first calling his attention to the great tree, the fruit, and the water he encountered–-most likely just minutes ago. There is a kind of divine power in these things that makes him and the rest of the gluttons look so terribly emaciated. Basically, there’s more than meets the eye with that tree. And isn’t that the point here? What meets the eye are souls ravaged by hunger. But the “more” here is what Forese wants Dante to understand. Beyond the singing and lamenting, there is the promise of salvation ahead of these souls, a deep soul-cleansing that is taking place within them, and the tree, the fruit, and the water are the means by which this cleansing takes place. And beyond the abundance of the tree which can be seen, Forese explains, the souls are deprived of its bounty, and they starve. In life, they ate everything in sight, as it were. Now, as though to play on the words, what they see they cannot have. And this is the contrapasso on this terrace.

It’s also interesting to note that Forese never mentions his own sin of gluttony when he was alive though, obviously, that’s why he’s here. And, for that matter, Dante makes no reference to it either. At the same time, it’s well to consider the sin of gluttony for a moment. We might simply think it’s a matter of over-eating. But it’s much more than that. It’s an intense, excessive passion for eating and drinking that goes beyond the control of reason. Food and drink–-one’s stomach, for that matter-–become the glutton’s god. It’s an addiction that often has bad health and social consequences. Medieval theologians, particularly St. Thomas Aquinas, listed many different types and categories of gluttony, and often linked it with other grave sins like avarice and greed.

7. Forese's last reference here, to Christ’s crying out ‘Eli' when he was dying on the cross, leads to some interesting theological insights. What might seem like a gratuitous devotional theme actually keeps the gluttons focused on the real object of their salvation–-namely Jesus, instead of the false god of food and drink. Moreover, it has been a constant in some devotional practices throughout the history of Christianity to welcome suffering, sometimes self-inflicted, as a way of uniting oneself with Jesus in h is own suffering. The thinking might go something like this: “It’s the least I can do for someone who has done so much for me.” After the Age of Martyrs, when Christianity became legalized under Constantine, some refer to the new era as the White Martyrdom. In this context, people weren’t killed for their faith, but might freely embrace a way of life (oftentimes monastic) where they “died to the world” in order to gain eternal life through penitence and self-denial.

Specifically, the word Eli refers to verse 1 of Psalm 22 which Jesus cried out before he died: “Eli, Eli, lama sabacthani?” “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” It might seem odd to the reader that Forese interprets these death-laden words with gladness. But his purpose is to look beyond the suffering and beyond the death to what follows: a victory over death manifested in Jesus’ resurrection and the cancellation of a debt of sin incurred by Adam and Eve at another tree in the Garden of Eden (see Genes is 3). Furthermore, there is no mistaking the fact that, in the commentary tradition of the Purgatorio, the two trees the gluttons encounter on this terrace (we will come to the second one in the following canto) are directly related to those of the two i n Eden. Recall that there were two trees in the Garden of Eden, one the Tree of Life, and the other the Tree of the Knowledge of Good and Evil. Adam and Eve ate from the latter tree and incurred death as a result. Robert Hollander comments here that “… the first sin of Adam and Eve, eating of the forbidden fruit of that tree deprived them of the fruit of the other one, eternal life. Thus Christ’s sacrifice (his death on the cross) is doubly restorative, redeeming the sin and restoring the reward.” Dorothy Sayers adds to this: “By a beautiful oxymoron Christ is said to have been glad when He uttered from the Cross His great cry of dereliction, because it sprang from His desire, or thirst, for man’s salvation.”

8. The value of prayers for those who have died has been a consistent theme in the Purgatorio, and it comes back here in Forese’s tender and grateful reminiscence of his virtuous wife’s prayers. One might infer here that she loved him in spite of his gluttony. Thus, we come to understand why Forese isn’t in Ante-Purgatory. Ronald Martinez notes here: “Not only has Nella cut short the penalty for Forese’s negligence, she has ‘freed’ him from the penances for pride, envy, anger, sloth, and avarice-–whether drastically shortening them or enabling him to skip them entirely.” In Forese’s eyes, she is a beacon of goodness compared with many other women of her generation. That he calls her Nella, a diminutive of Giovanna and Giovanella, is another mark of how tenderly he remembers her. Many commentators suggest that this is also Dante’s way of making up for the rather vulgar poems he and Forese used to shoot at each other when they were young. In some of them, Dante teasingly mocked Nella and accused Forese of neglecting her. And as I noted earlier, there are still disputes about the authenticity of these “darts.”

That Nella was a virtuous Florentine woman is highlighted by Forese’s comparison of them to the women of the Barbagia, at that time a wild and savage region in the mountains of Sardinia where the women were said to go about naked. They are more virtuous than the shameless women of Florence.

9. Forese was just warming up in the previous paragraph when he suggested that the savage women of the Bargabia region in Sardinia were more virtuous than contemporary Florentine women. Here, he unleashes a venomous prophecy against these lascivious women whose lack of modesty and restraint (a kind of “clothing version” of gluttony) will soon have serious consequences. Some commentators note a decree about this by the bishop of Florence in 1310. As it turns out, though, there seems to have been no such decree. B ut recalling that Dante wrote the Purgatorio several years after the year 1300 in which it is set, there may have been sumptuary laws against women’s dresses that were extravagant and far too revealing. He then puts mention of this in Forese’s mouth as a “prophecy”–-most likely more of a warning.

10. Forese's sister is Piccarda, see above.

Top of page