Dante's Divine Comedy: Purgatorio

Canto XVIII

Virgil continues the discourse begun in Canto XVII by addressing the origin and nature of Love, the concept of the rational soul (as distinct from the material body) and determinism versus free will. Just as Dante is drifting off to sleep, he is awakened by the noisy spirits of the Slothful. Apathetic or indifferent to life, their penance now demands ceaseless activity as they rush around the Fourth Cornice, crying out examples of active Zeal, the opposing virtue, which serve as the Whip and Bridle for their meditation. The Abbot of San Zeno gives Virgil directions. Dante falls into a slumber.

An end had put unto his reasoning

The lofty Teacher, and attent was looking

Into my face, if I appeared vivified

And I, whom a new thirst still goaded on,

Without was mute, and said within: "Perchance

The too much questioning I make annoys him."

But that true Father, who had comprehended

The timid wish, that opened not itself,

By speaking gave me hardihood to speak.

Whence I: “My sight is, Master, vivified

So in thy light, that clearly I discern

Whate’er thy speech importeth or describes.

Therefore I thee entreat, sweet Father dear,

To teach me love, to which thou dost refer

Every good action and its contrary.”

“Direct,” he said, “towards me the keen eyes

Of intellect, and clear will be to thee

The error of the blind, who would be leaders.[1]

The soul, which is created apt to love,

Is mobile unto everything that pleases,

Soon as by pleasure she is waked to action.[2]

Your apprehension from some real thing

An image draws, and in yourselves displays it

So that it makes the soul turn unto it.

And if, when turned, towards it she incline,

Love is that inclination; it is nature,

Which is by pleasure bound in you anew

Then even as the fire doth upward move

By its own form, which to ascend is born

Where longest in its matter it endures,

So comes the captive soul into desire,

Which is a motion spiritual, and ne’er rests

Until she doth enjoy the thing beloved.

Now may apparent be to thee how hidden

The truth is from those people, who aver

All love is in itself a laudable thing;[3]

Because its matter may perchance appear

Aye to be good; but yet not each impression

Is good, albeit good may be the wax.”[4]

“Thy words, and my sequacious intellect,”

I answered him, “have love revealed to me;

But that has made me more impregned with doubt;

For if love from without be offered us,

And with another foot the soul go not,

If right or wrong she go, ‘tis not her merit.”

And he to me: “What reason seeth here,

Myself can tell thee; beyond that await

For Beatrice, since ‘tis a work of faith.[5]

Every substantial form, that segregate

From matter is, and with it is united,

Specific power has in itself collected,

Which without act is not perceptible,

Nor shows itself except by its effect,

As life does in a plant by the green leaves.

But still, whence cometh the intelligence

Of the first notions, man is ignorant,

And the affection for the first allurements,

Which are in you as instinct in the bee

To make its honey; and this first desire

Merit of praise or blame containeth not.

Now, that to this all others may be gathered,

Innate within you is the power that counsels,

And it should keep the threshold of assent.

This is the principle, from which is taken

Occasion of desert in you, according

As good and guilty loves it takes and winnows.

Those who, in reasoning, to the bottom went,

Were of this innate liberty aware,

Therefore bequeathed they Ethics to the world.

Supposing, then, that from necessity

Springs every love that is within you kindled,

Within yourselves the power is to restrain it.

The noble virtue Beatrice understands

By the free will; and therefore see that thou

Bear it in mind, if she should speak of it.”[6]

The moon, belated almost unto midnight,

Now made the stars appear to us more rare,

Formed like a bucket, that is all ablaze,[7]

And counter to the heavens ran through those paths

Which the sun sets aflame, when he of Rome

Sees it ‘twixt Sardes and Corsicans go down;

And that patrician shade, for whom is named

A Pietola more than any Mantuan town,

Had laid aside the burden of my lading;[8]

Whence I, who reason manifest and plain

In answer to my questions had received,

Stood like a man in drowsy reverie.

But taken from me was this drowsiness

Suddenly by a people, that behind

Our backs already had come round to us,[9]

And as, of old, Ismenus and Asopus

Beside them saw at night the rush and throng,

If but the Thebans were in need of Bacchus,[10]

So they along that circle curve their step,

From what I saw of those approaching us,

Who by good-will and righteous love are ridden.

Full soon they were upon us, because running

Moved onward all that mighty multitude,

And two in the advance cried out, lamenting,

“Mary in haste unto the mountain ran,

And Caesar, that he might subdue Ilerda,

Thrust at Marseilles, and then ran into Spain.”[11]

“Quick! quick! so that the time may not be lost

By little love!” forthwith the others cried,

“For ardor in well-doing freshens grace!”

“O folk, in whom an eager fervor now

Supplies perhaps delay and negligence,

Put by you in well-doing, through lukewarmness,

This one who lives, and truly I lie not,

Would fain go up, if but the sun relight us;

So tell us where the passage nearest is.”

These were the words of him who was my Guide;

And some one of those spirits said: “Come on

Behind us, and the opening shalt thou find;

So full of longing are we to move onward,

That stay we cannot; therefore pardon us,

If thou for churlishness our Justice take,[12]

I was San Zeno’s Abbot at Verona,

Under the empire of good Barbarossa,

Of whom still sorrowing Milan holds discourse;[13]

And he has one foot in the grave already,

Who shall erelong lament that monastery,

And sorry be of having there had power,

Because his son, in his whole body sick,

And whose in mind, and who was evil-born,

He put into the place of its true pastor."[14]

If more he said, or silent was, I know not,

He had already passed so far beyond us;

But this I heard, and to retain it pleased me.

And he who was in every need my succor

Said: “Turn thee hitherward; see two of them

Come fastening upon slothfulness their teeth.”

In rear of all they shouted: “Sooner were

The people dead to whom the sea was opened,

Than their inheritors the Jordan saw;[15]

And those who the fatigue did not endure

Unto the issue, with Anchises’ son,

Themselves to life withouten glory offered.”[16]

Then when from us so separated were

Those shades, that they no longer could be seen,

Within me a new thought did entrance find,

Whence others many and diverse were born;

And so I lapsed from one into another,

That in a reverie mine eyes I closed,

And meditation into dream transmuted.

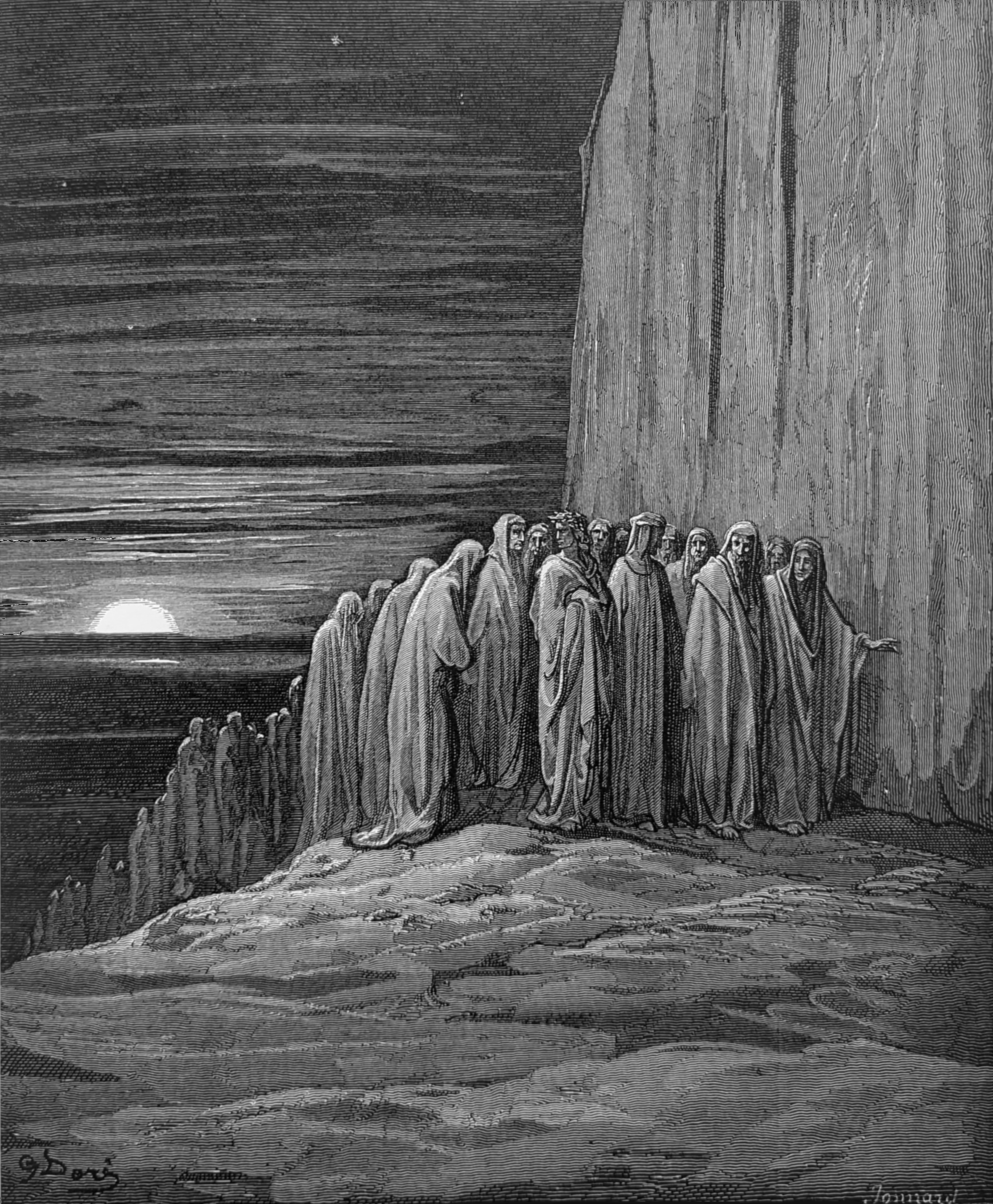

Illustrations of Purgatorio

But taken from me was this drowsiness / Suddenly by a people, that behind / Our backs already had come round to us. Purg. XVIII, lines 88-90

Footnotes

1. The reference to the blind leading the blind comes from St. Matthew’s Gospel (15:14), where Jesus warns his disciples against the teaching of the Pharisees: “They are blind guides of the blind. But if a blind person guides another blind person, both will fa ll into a pit.”

2. Virgil begins by recapping what he has already described as “natural love,” that love which draws us instinctively toward the Creator whose love created us and draws us toward himself. The soul, he tells Dante, is basically made for–-inclined toward-–love, and is drawn toward whatever pleases it. What it sees, the soul/mind creates an image of it and moves you toward it–-the working of the imagination. This is the action of natural love in the soul. Virgil demonstrates this using the simple image of a flame, which, by its nature always burns upward.

3. Aver, Latin, vērus, “true”.

4. It’s at this point that Virgil turns toward an explanation of misdirected love. He does this by reference to, and subtly warning Dante against, Epicurean philosophy, whose followers are those blind guides he warned against above. They believe that love, as desire, is always good and should be pursued and gratified. But this is a dangerous path to follow as it can justify a love of excess instead of a love guided by free will toward temperance and moderation. Here, Dante is influenced by Aristotle’s De Anima (On the Soul) and Metaphysics as were other great Medieval thinkers. He concludes with another image involving wax and a seal impressed on it. The good wax is symbolic of our instinctive movement toward love. The stamp or “impression” represents the image our mind/imagination creates out of what it sees or is drawn to. But not every object/impression we love is good. It can also be bad.

5. Note that Virgil’s reference to Dante’s need to appeal to reason and faith here also points to Virgil’s and Beatrice’s roles as representing Reason (philosophy) and Faith. Virgil will answer as far as reason can take him; Beatrice will complete the picture from the point of view of revelation and the Christian faith.

Our souls are distinct from matter, and the characteristics that make our souls unique join together to operate in a mysterious way, such that we cannot actually “see” them working, but we can see their effects. Thus, the example of the green leaves, and so also with workings of the soul. We don’t know precisely where our knowledge of things like truth or goodness, or even God, come from. We also don’t know exactly why we’re attracted to these things. But we are. And this is within the nature of who we are as beings. Thus, the example of the bees.

6. Virgil here is speaking about free will. When joined with the powers of intellect and reason it gives us the ability to choose good or bad. On these choices are based merit or blame. And as he has already explained, there are various kinds of love, and it i s our free will that enables us to choose the best among them. Long ago, he tells Dante, great thinkers had already worked this out and laid the foundations for ethical behavior. Finally, it’s fascinating here that Virgil anticipates Beatrice’s explanation of free will in Canto 5:19ff of the Paradiso. Her words are remarkable: “The greatest gift that our bounteous Lord bestowed as the Creator, in creating, the gift He cherishes the most, the one most like Himself, was freedom of the will. All creatures with intelligence, and they alone, were so endowed both then and now.”

Going back to Canto 3 of the Inferno for a moment, Virgil had already reminded the Poet that the souls in hell were there because they chose to be there. They had (freely) lost the good of the intellect and were no better than animals.

7. The second part of this canto begins here, and if it’s close to midnight, then Dante’s questions and Virgil’s “lectures” have gone on for several hours. There are several things one can note about the moon here. Several nights ago (Thursday, to be exact), t he moon was full when Dante entered the dark wood. Now, five nights later, it is gibbous and looks like a bucket because it’s illuminated half is turned downward. Its brightness, like a polished bucket (which some commentators say is red or burnished), is probably due to its closeness to the horizon. The fact that it’s waning and, according to Dante, the slowest of the planets, also makes it a fitting image of the sloth that’s punished on this terrace. In his commentary, Mark Musa presents a clear picture of what Dante is describing in this passage:

“The moon is following its monthly course in the direction from West to East by the process of gradual retardation. In the complicated astronomical figure contained in this tercet we are told that the moon was in the same path of the zodiac which the sun follows when the people of Rome (looking westward) see it setting on a line between Sardinia and Corsica. According to Moore (1887, pp. 104-105) this happens in late November when the sun is in Sagittarius, and this is exactly where the moon would be on this night of April in Purgatory.”

8. Virgil was born in the town of Pietola, about five miles southeast of Mantua. In lavishing more praise on his illustrious mentor, who answered his questions so elegantly, Dante even mentions Virgil’s hometown as now being famous. But, at this late hour, bot h teacher and student are weary. Dante seems to follow his mentor in letting his mind rest and his thoughts wander. Again, Mark Musa offers some fascinating insights: “It is curious that here Virgil is given a different mythical dimension in the parallel be tween him and the moon: as the moon outshines the light of the stars, Virgil, it seems, takes center stage in all of his region through the name of his tiny village. That he might resemble the moon in its other particulars lends further symbolic interest to this passage.”

9. It has been a long day for Dante and Virgil. Having learned much from Marco the Lombard, and later from Virgil, the Poet’s drowsiness anticipates the last experience of this day-–his encounter with the souls of the slothful. As noted in the previous canto, sloth is not simply laziness, it is far more insidious. In her commentary on this canto, Dorothy Sayers is masterful as she defines this terrible sin, also known as acedia:

“It is not merely idleness of mind and laziness of body, it is that whole poisoning of the will which, beginning with indifference and an attitude of ‘I couldn’t care less,’ extends to the deliberate refusal of joy and culminates in morbid introspection and despair. One form of it which appeals very strongly to some modern minds is that acquiescence in evil and error which readily disguises itself as ‘Tolerance’; another is that refusal to be moved by the contemplation of the good and beautiful which is kn own as ‘Disillusionment,’ and sometimes as ‘knowledge of the world’; yet another is that withdrawal into an ‘ivory tower’ of Isolation which is the peculiar temptation of the artist and the contemplative, and is popularly called ‘Escapism.’ The penance assigned to it takes the form of the practice of the opposite virtue: an active Zeal. Note that on this Cornice alone no verbal Prayer is provided for the penitents: for them, “to labor is to pray.”

10. The frenzied racing around behind them-–in the middle of the night-–is totally unexpected by the two drowsy travelers who are probably sitting near the stairs looking out at the grand view before them (the sea, the Mountain, the moon, the stars). With classical references ever at his disposal, Dante’s surprise at the crazed scene they behold reminds him of what he had read (and “seen”) about the wild cult of Bacchus in Ovid’s Metamorphoses and Statius’ Thebaid. Thebes was the center of this cult, and ancient lurid images of the nocturnal orgiastic rituals along the banks of the rivers Ismenus and Asopus near Thebes seem to have filled Dante’s imagination as he took in this unexpected scene. And then, as though remembering where he is, he moves from a scene of riotous pagan worship to the almost mad pursuit of virtue. The whole scene here lies in stark contrast to the elegant intellectual disquisitions of the first half of this canto.

11. These slothful souls–-a great crowd of them–-are actually practicing the virtue opposite to their sin by racing along the terrace with such fervor. The “Whip of Sloth” is seen in the examples cried out by two souls in the lead. The first is a scene from chapter 1 of St. Luke’s Gospel. When the angel Gabriel had announced to the Virgin Mary that she would be the mother of Jesus (the Annunciation), he also told her that her barren cousin, Elizabeth, was also with child. When the vision ended, Mary went to the h ill country to visit her cousin (the Visitation), whose son would be John the Baptist. The second scene is from Lucan’s Pharsalia, wherein he recounts how Julius Caesar, after subduing the city of Marseilles, went on to subdue the city of Ilerda (Lerida). Then, as this race of souls passes by, shouts of “Faster!” can be heard from behind, along with this wonderful reminder: “We cannot waste time, for time is love.” Recall how, in the earlier part of this canto, Virgil explained to Dante how we were created by a loving Creator whose love fills us and holds us in being. Our natural inclination is to return that love to God by choosing Him above all else, by works of virtue, and by using the goods of this world with moderation. These slothful souls, as noted above in the explanation of acedia, may have grasped this moral principle intellectually, but did little to put it into action. Thus, they race about in a frenzy reminding themselves of the time they wasted in loving too little.

12. Churl, Middle English, churl, cherl, cheorl, a free peasant.

13. Recall that the movement here is counter-clockwise. Also, one notices that there is no particular prayer said by the penitent souls here as on other terraces. Probably because there’s no time to stop and pray, as it were. Their movement is their prayer. This reader finds it rather comical that the souls here politely apologize for their seeming rudeness in not stopping to talk, yet the Abbot of San Zeno, apparently named Gherardo, has time to praise the emperor Frederick Barbarossa and bad-mouth the p resent Abbot of his monastery.

The Benedictine monastery and church of San Zeno in Verona was undoubtedly familiar to Dante who, during a good part of his exile, was the guest of the Scala family, lords of the city. The splendid church was still under construction when Dante was there. T hough Shakespeare tells us that Romeo and Juliet were married by Friar Lawrence, probably in this monastery, there is a legend that the chapel in its crypt is where the wedding took place.

14. Gherardo, the speaker here, about whom we know very little, was apparently hospitable to the emperor Frederick, who later rewarded him by making him Abbot of San Zeno. This is most likely why he is called “the good Barbarossa.” As for the rebellious Milanese, Frederick destroyed their city in 1167, almost a hundred years before Dante was born. The “man close to death” is another reference to the Scala family-–this time Alberto della Scala, who died in 1301. In 1300, when the Poem is set, he would definitely b e near death. Alberto had three sons: Bartolomeo, Alboino, and Francesco (called Cangrande, who was Dante’s host). In 1292, in violation of church law, Alberto forced the appointment of his, mentally deficient, illegitimate, and physically handicapped son, Giuseppe, as Abbot of San Zeno, the deed Gherardo resents in this passage. Benvenuto da Imola writes of him in his commentary: “He was a mean man … a rapacious wolf, a violent man, roaming the outskirts of the city by night with armed companions, destroying much and filling the place with harlots.”

15. In the first story, to give it some context, the long journey of the Israelites from bondage in Egypt to freedom in the Promised Land (geographically and time-wise) was punctuated by numerous infidelities and mutinies. The reference here to the death of those who crossed the Red Sea marks the place in Chapter 14 in the Book of Numbers where God finally punished the people for their constant complaints, stating that only those under 21years of age would enter the Promised Land. The rest would wander in the wilderness outside for another 40 years.

16. The second story comes from Virgil’s Aeneid (Book 5:604-776). It bears a remarkable similarity to the story of the rebellious Israelites in the previous allusion. Several of Aeneas’ followers were dispirited by the length and hardships of their voyages an d choose not to follow him from Sicily toward his destiny (and their shared glory) on the mainland. However, this story differs from the one in the Book of Numbers because Aeneas, in fact, allowed that group of laggards to stay.

Top of page