Dante's Divine Comedy: Purgatorio

Canto XXIV

Forese rejoices that his sister, Piccarda, is in Heaven and points to Bonagiunta of Lucca, a thirteenth-century poet. Dante and Bonagiunta discuss the state of poetry and the Florentine school's dolce stil nuovo (sweet new style), which conceives of Love as a power of divine origin, devoid of the sensual elements of courtly love. At the second tree, a voice rehearses examples from the Bridle of Gluttony. The Angel of Temperance wipes off the sixth P, utters the benediction, "Blessed Are They Who Hunger After Righteousness" and shows the way to the next cornice by the Pass of Pardon.

Nor speech the going, nor the going that

Slackened; but talking we went bravely on,

Even as a vessel urged by a good wind.

And shadows, that appeared things doubly dead,

From out the sepulchers of their eyes betrayed

Wonder at me, aware that I was living.

And I, continuing my colloquy,

Said: "Peradventure he goes up more slowly

Than he would do, for other people's sake.

But tell me, if thou knowest, where is Piccarda;

Tell me if any one of note I see

Among this folk that gazes at me so."[1]

"My sister, who, 'twixt beautiful and good,

I know not which was more, triumphs rejoicing

Already in her crown on high Olympus."

So said he first, and then: "Tis not forbidden

To name each other here, so milked away

Is our resemblance by our dieting.

This," pointing with his finger, "is Bonagiunta,

Bonagiunta, of Lucca; and that face

Beyond him there, more peaked than the others,[2]

Has held the holy Church within his arms;

From Tours was he, and purges by his fasting

Bolsena's eels and the Vernaccia wine."

He named me many others one by one;

And all contented seemed at being named,

So that for this I saw not one dark look.

I saw for hunger bite the empty air

Ubaldin dalla Pila, and Boniface,

Who with his crook had pastured many people.[3]

I saw Messer Marchese, who had leisure

Once at Forli for drinking with less dryness,

And he was one who ne'er felt satisfied.[4]

But as he does who scans, and then doth prize

One more than others, did I him of Lucca,

Who seemed to take most cognizance of me.

He murmured, and I know not what Gentucca

From that place heard I, where he felt the wound

Of justice, that doth macerate them so.[5]

"O soul," I said, "that seemest so desirous

To speak with me, do so that I may hear thee,

And with thy speech appease thyself and me."

"A maid is born, and wears not yet the veil,"

Began he, "who to thee shall pleasant make

My city, howsoever men may blame it.

Thou shalt go on thy way with this prevision;

If by my murmuring thou hast been deceived,

True things hereafter will declare it to thee.

But say if him I here behold, who forth

Evoked the new-invented rhymes, beginning,

'Ladies, that have intelligence of love?' "[6]

And I to him: "One am I, who, whenever

Love doth inspire me, note, and in that measure

Which he within me dictates, singing go."

"O brother, now I see," he said, "the knot

Which me, the Notary, and Guittone held

Short of the sweet new style that now I hear.[7]

I do perceive full clearly how your pens

Go closely following after him who dictates,

Which with our own forsooth came not to pass;

And he who sets himself to go beyond,

No difference sees from one style to another;"

And as if satisfied, he held his peace.

Even as the birds, that winter tow'rds the Nile,

Sometimes into a phalanx form themselves,

Then fly in greater haste, and go in file;[8]

In such wise all the people who were there,

Turning their faces, hurried on their steps,

Both by their leanness and their wishes light.

And as a man, who weary is with trotting,

Lets his companions onward go, and walks,

Until he vents the panting of his chest;

So did Forese let the holy flock

Pass by, and came with me behind it, saying,

"When will it be that I again shall see thee?"

"How long," I answered, "I may live, I know not;

Yet my return will not so speedy be,

But I shall sooner in desire arrive;

Because the place where I was set to live

From day to day of good is more depleted,

And unto dismal ruin seems ordained."

"Now go," he said, "for him most guilty of it

At a beast's tail behold I dragged along

Towards the valley where is no repentance.[9]

Faster at every step the beast is going,

Increasing evermore until it smites him,

And leaves the body vilely mutilated.

Not long those wheels shall turn," and he uplifted

His eyes to heaven, "ere shall be clear to thee

That which my speech no farther can declare.

Now stay behind; because the time so precious

Is in this kingdom, that I lose too much

By coming onward thus abreast with thee."

As sometimes issues forth upon a gallop

A cavalier from out a troop that ride,

And seeks the honor of the first encounter,

So he with greater strides departed from us;

And on the road remained I with those two,

Who were such mighty marshals of the world.

And when before us he had gone so far

Mine eyes became to him such pursuivants

As was my understanding to his words,

Appeared to me with laden and living boughs

Another apple-tree, and not far distant,

From having but just then turned thitherward.[10]

People I saw beneath it lift their hands,

And cry I know not what towards the leaves,

Like little children eager and deluded,

Who pray, and he they pray to doth not answer,

But, to make very keen their appetite,

Holds their desire aloft, and hides it not.

Then they departed as if undeceived;

And now we came unto the mighty tree

Which prayers and tears so manifold refuses.

"Pass farther onward without drawing near;

The tree of which Eve ate is higher up,

And out of that one has this tree been raised."

Thus said I know not who among the branches;

Whereat Virgilius, Statius, and myself

Went crowding forward on the side that rises.

"Be mindful," said he, "of the accursed ones

Formed of the cloud-rack, who inebriate

Combated Theseus with their double breasts;[11]

And of the Jews who showed them soft in drinking,

Whence Gideon would not have them for companions

When he tow'rds Midian the hills descended."[12]

Thus, closely pressed to one of the two borders,

On passed we, hearing sins of gluttony,

Followed forsooth by miserable gains;

Then set at large upon the lonely road,

A thousand steps and more we onward went,

In contemplation, each without a word.

Thence is it that we speak, and thence we laugh;

Thence is it that we form the tears and sighs,

That on the mountain thou mayhap hast heard.

According as impress us our desires

And other affections, so the shade is shaped,

And this is cause of what thou wonderest at."

And now unto the last of all the circles

Had we arrived, and to the right hand turned,

And were attentive to another care.

There the embankment shoots forth flames of fire,

And upward doth the cornice breathe a blast

That drives them back, and from itself sequesters.

Hence we must needs go on the open side,

And one by one; and I did fear the fire

On this side, and on that the falling down.

My Leader said: "Along this place one ought

To keep upon the eyes a tightened rein,

Seeing that one so easily might err."

"Summae Deus clementiae," in the bosom

Of the great burning chanted then I heard,

Which made me no less eager to turn round;

And spirits saw I walking through the flame;

Wherefore I looked, to my own steps and theirs

Apportioning my sight from time to time.

After the close which to that hymn is made,

Aloud they shouted, "Virum non cognosco;"

Then recommenced the hymn with voices low.[13]

This also ended, cried they: "To the wood

Diana ran, and drove forth Helice

Therefrom, who had of Venus felt the poison."

Then to their song returned they; then the wives

They shouted, and the husbands who were chaste

As virtue and the marriage vow imposes.

And I believe that them this mode suffices,

For all the time the fire is burning them;

With such care is it needful, and such food,

That the last wound of all should be closed up.

Illustrations of Purgatorio

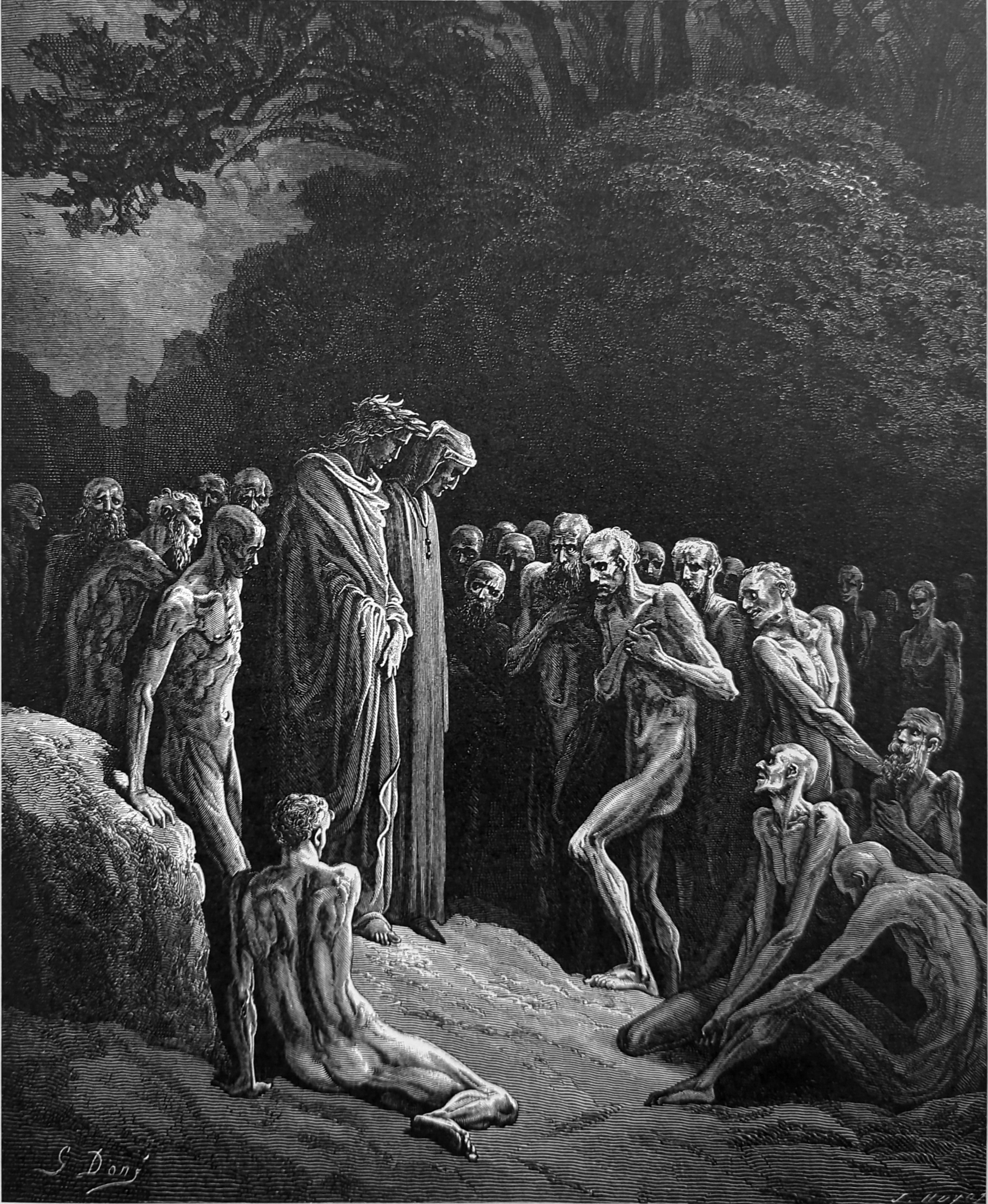

And shadows, that appeared things doubly dead, / From out the sepulchres of their eyes betrayed / Wonder at me, aware that I was living. Purg. XXIV, lines 4-6

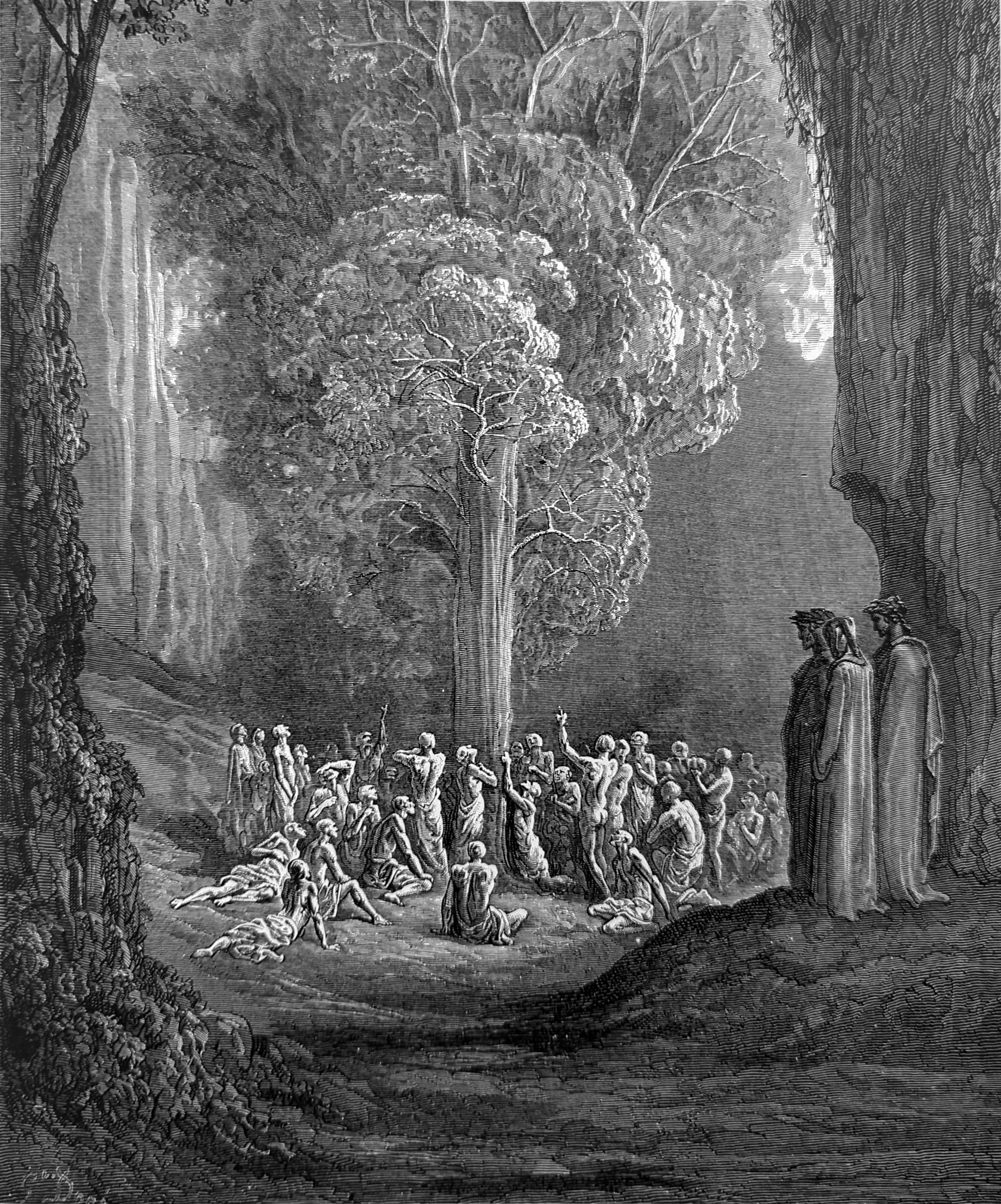

People I saw beneath it lift their hands, / And cry I know not what towards the leaves, Purg. XXIV, lines 106-107

Footnotes

1. Piccarda is now in Paradise, and we will meet her there in Canto 3. As a teenager, she entered the convent of the Sisters of St. Clare of Assisi at Monticelli near Florence. Later, her wicked older brother, Corso, leader of the Black Guelfs, forced her out of the convent in order to marry her to his chief henchman, Rosselliono della Tosa. (According to Dorothy Sayers, she had been previously engaged to him.) She died shortly after the wedding. Robert Hollander’s commentary here notes a connection between Piccarda, Pia de’ Tolomei (Purg. 3), and Francesca da Rimini (Inf. 5)–-all of whom had been forced into undesirable marriages.

Note also how Dante subtly links his epic poem with those of classical times by Forese’s telling him that Piccarda is “crowned in triumph on High Olympus.”

2. Five gluttonous penitents are named here. The first is Bonagiunta Orbicciani degli Overardi from Lucca (25 miles west of Florence). He was a noted poet, and several of his works survive today. He died in 1297. Dante may have known him personally, but he did criticize the rather formal style of his work in De Vulgari Eloquentia (I,XIII,1ff):

“After this, we come to the Tuscans, who, rendered senseless by some aberration of their own, seem to lay claim to the honor of possessing the illustrious vernacular. And it is not only the common people who lose their heads in this fashion, for we find that a number of famous men have believed as much: like Guittone d’Arezzo, who never even aimed at a vernacular worthy of the court, or Bonagiunta da Lucca, or Gallo of Pisa, or Mino Mocato of Siena, or Brunetto the Florentine, all of whose poetry, if there were space to study it closely here, we would find to be fitted not for a court but at best for a city council.”

Benvenuto da Imola, in his commentary, says this of Bonagiunta: “This was Bonagiunta Orbicciani, an honorable man, of the city of Lucca, a brilliant orator in the mother tongue, with a great facility in finding rhymes but more adept at finding wines. He knew the author while he was alive and sometimes wrote to him. Hence, the author portrays him as conversing with him in friendly fashion about himself and other modern poets.”

3. The first in this group is Ubaldino della Pila. He was a knight and a member of the Ubaldini family of Florence. His brother was Cardinal Ottaviano, placed among the Epicureans with Farinata in Canto 10 of the Inferno. He was also the father of Archbishop Ruggieri of Pisa, who betrayed Count Ugolino da Gherardesca, and whose brains Ugolino now feasts on at the bottom of Hell in Inferno Canto 33. After the famous Battle of Montaperti in 1260, it was Ubaldino who pushed for the destruction of Florence, but was stopped by Farinata degli Uberti (Inf. 10).

Obviously, Ubaldino was known as a glutton, for which he had a widespread reputation. At the same time, he was also noted for his culinary acumen and inventive recipes. He died in 1291. He and the next glutton Dante mentions, are seen here in such straits o f starvation that they chomp at the air-–a kind of pantomime of eating. Dante takes this image from Ovid’s Metamorphoses (VIII, 824ff) and the story of the punishment of Erysichthon, noted toward the beginning of the last canto: “He reaches for the food a s he dreams its image, moves his lips in vain and grinds tooth against tooth; his deceived throat tries to swallow the nonexistent food, and instead of a banquet he devours thin air.”

Next in this group is Boniface, Archbishop of Ravenna. He was probably the very wealthy Bonifazio dei Fieschi of Genoa. One of the symbols of the bishop’s office is the large shepherd’s crook that he carries in formal settings and processions. It symbolizes the bishop’s role as a shepherd of souls. Dante, in the Italian, sarcastically plays with the words here and suggests that Boniface was more of a “shepherd to the bellies rather than the souls of his archdiocese” (Ciardi). At the same time, there appears to be no historical evidence that Boniface was a glutton! He died in 1295. What was Dante up to?

4. “Messer Corso, who had fled alone, was overtaken and captured at Rovezzano (a suburb southeast of Florence) by certain Catalan horsemen. They were taking him prisoner to Florence and were near San Salvi, when he begged them to let him go, promising large sums of money in return. But those men were determined to take him back to Florence, as they had been ordered to do by the priors. Because he was so afraid of falling into the hands of his enemies and being executed by the people, Messer Corso, being badly afflicted with gout in his hands and feet, let himself fall from his horse. Seeing him on the ground, one of the Catalans thrust a lance through his throat, dealing him a mortal blow; and they left him for dead.”

Another account has Corso falling from his horse while he was being pursued and stabbed in the throat by his pursuers. Yet another one has it that he fell from his horse, but his foot caught in a stirrup and he was dragged, mangled, and kicked to death by t he horse. In some places, as a matter of fact, being dragged to death by a horse was the punishment of traitors. Then there are also legends of evil people being dragged down into Hell by wild horses. Regardless, the evil Corso met his death on October 6, 1 308. And remembering that Dante sets his Poem in the Spring of 1301, Forese’s narrative is a kind of “prophecy” that avenges Dante for what happened to him at the hands of his brother.

5. As for Gentucca, the identification of this person has plagued commentators for generations, not helped by the fact that Dante tells us that Bonagiunta murmured the word. It might be a crude play on the Italian word for people, gente, implying that they a re country bumpkins. But most commentators suggest that it refers to an unidentified gentlewoman who offered Dante hospitality when he passed through Luccan territory early on in his exile. And generally discounted as specious is the hypothesis that she was a woman with whom Dante had a sexual dalliance. Francesco Buti, lecturing on the Commedia about 60 years after Dante’s death, notes the following:

“The author (Dante) pretends he does not understand, because, according to the fiction he has created, the things predicted and announced here have not yet taken place, i.e., that he would be banished from Florence to Lucca and that he would fall in love there with a gentle lady called Gentucca. This had happened before the author wrote this part: the author, in Lucca because he was unable to remain in Florence, fell in love with a gentle lady called Madonna Gentucca, of the Rossimpelo family. He loved her for the great virtue and honesty that were in her, not with any other love.”

6. Let us remember, first of all, that Bonagiunta already knew Dante, and his words here aren’t so much an interrogation as they are a way of expressing praise for Dante’s creation of something quite new in poetic expression. “Ladies who have intelligence of Love,” is the centerpiece poem in Dante’s Vita Nuova. Ronald Martinez notes here that for Dante, this poem represented “the major turning point in his early poetry, from self-regarding poetry to the poetry of praise.” Robert Hollander notes that Dante may have included this brief encounter with Bonagiunta in order to highlight his own poetical work. Later, he writes: “Dante composed this poem around 1289. From this remark, we learn at least one important thing. Whatever the determining features of Dante’s ne w poetry, it was different–-at least according to him, using Bonagiunta as his mouthpiece–-from all poetry written before it, including Dante’s own…. It seems clear that Dante’s absolute and precise purpose is to rewrite the history of Italian lyric, including that of his own poems, so that it fits his current program.”

In this poem, which is the subject of the conversation here, Dante had made a distinct turn from the traditional notion of love as sensual or erotic love to something definitely more spiritual–-the Holy Spirit of God. This Spirit “in-spires” (breathes into) the poet with an understanding of love which is elevated and which strives, in this case with words, to reflect the highest Good, the beauty of the divine Creator who infuses all creation with love. This becomes his new way of writing poetry–-his dolce stil novo. And Bonagiunta happily recognizes how profound and effective it is compared with his own style.

7. Bonagiunta also mentions two notable fellow poets who, along with him, failed to see the direction Dante’s poetry was taking: Giacomo da Lentini (d. 1250) and Guittone d’Arezzo (d. 1294). According to Charles Singleton, both poets belonged to what was known of the “Sicilian” school of poetry (recall Pier delle Vigne in Canto 13 of the Inferno who was also of that school). Lentini (called “the Notary”) studied in Bologna and lived in Tuscany where he was regarded as the chief of the lyric poets before Guittone. Mark Musa writes that Lentini is credited with being the probable inventor of the sonnet.

8. This is an interesting image to follow upon Dante’s “flying” poetry. The birds (cranes) that line up are an image of the poets who learn from and follow their leader–in this case Dante.

9. Dante did not encounter Corso Donati in Hell, but Forese definitely puts him there, laying much of the evil that had befallen Florence at Corso’s feet. In the end, he got what he deserved. Here’s the background. Corso was the leader of the Black Guelfs in Florence. In 1301 he persuaded Pope Boniface VIII (some suggest that he is the “beast” Corso is dragged behind) to send Charles of Valois (brother of the King of France) into Florence under the guise of keeping the peace between the warring factions. Charles entered the city with his French troops, but only for a short time. In the mean time, Corso, with a vicious band of Black party thugs, came into Florence shortly after Charles and set out on a five-day rampage, opening the prisons, murdering members of the White Guelf party, burning and sacking their property, and sending them into exile. Charles did nothing to stop this and left the city. Dante, in fact, was in Rome at this time and was subsequently exiled in absentia. In the next several years, Corso attempted to bribe and corrupt his way to supreme leadership of the Black Guelfs and lord of Florence. But his arrogance caught up with him. He never achieved the supreme leadership, but was, instead, condemned to death for treason by his own party in 1308. They had had enough of him.

10. As the three poets continue walking around this terrace and Dante loses sight of Forese, they come upon a second tree in the middle of their path. Unlike the first tree they had encountered, this one doesn’t seem to be “upside down” and splashed with water from above (though there are a few commentators who argue that this tree is identical to the earlier one). At the same time, like the first tree it is laden with delicious-looking fruit which amplifies the gluttons’ hunger. Dante sees them standing by t he tree with arms outstretched as though they were begging-–from someone who wouldn’t give them anything. The hungry sinners give up and run away. Note, by the way, that Forese is not among these sinners. He’s most likely making up for lost time.

Painful as it may be, being sent away from the tree strengthens the sinners’ resolve to “grow up” and continue their penance. The reference to “foolish greedy children” harkens back to Dante’s Convivio (IV.xii.16) where he writes: ”Thus we see little children setting their desire first of all on a fruit, and then, growing older, desiring to possess a little bird, and then still later desiring to possess fine clothes, then a horse, and then a woman, and then modest wealth, then greater riches, and then still m ore.”

Since this terrace is closer to the top of the Mountain of Purgatory, it is smaller than all those below it. This being the case, though it seems obvious, part of the gluttons’ contrapasso is to repeat this ritual at the forbidden trees again and again. O ne might imagine a newly-arrived soul who is quite fat starting their rounds and, being refused food and drink at every turn, they quickly become thinner and thinner until, as Dante describes them, they’re nothing but skin and bones.

11. The mysterious voice in this second tree now recounts two more examples that act as “reins” against the sin of gluttony: one is from classical literature, the other is from the Hebrew Bible.

The first example is from Ovid’s Metamorphoses (XII:210-535), a scene of chaos, blood and guts 300 lines long that erupts at a wedding party. This admonition from the tree basically centers around the marriage of Pirithous, King of the Lapiths, and Hippodamia, daughter of the King of the Grecian city of Pisa. Pirithous invited his best friend, the famous Theseus (who captured the Minotaur). Unfortunately, he also invited his cousins, the centaurs: half-men, half horses, who were descended from Ixion, Pirithous’s father, and Nephele, a cloud-goddess. They were noted for being crude and barbaric. The wedding feast descended into chaos when the centaurs became wildly drunk. Eurytus, half-brother of Pirithous, and wildest of the centaurs, attempted to carry o ff Hippodamia to rape her. His brother centaurs attempted the same with the other women present. The women were rescued, but a fight of epic proportions ensued and the centaurs were defeated.

12. The last admonition comes from the Hebrew Bible in Chapter 7 of the Book of Judges. In summary, Gideon was told by God to lead the Hebrew soldiers to drink from the River Jordan where he would decide which ones he would keep and which he would send home . Some soldiers kept their guard up and scooped the water into their hands and drank that way. The others abandoned their caution, immersed themselves in the river and drank that way. Gideon kept those who remained on guard. Mark Musa makes Dante’s point cl ear here: “Thus it is not only how much a person eats or drinks but also the manner in which God’s gifts are approached that determines the sin of gluttony. These soldiers who were chosen to go on possessed the virtue of restraint.”

13. Virum non cognosco, Latin, "I don't know the man".

"Virum non cognosco" is a phrase meaning "I know not man," spoken by the Virgin Mary in the Bible when the angel Gabriel announces her pregnancy. In Dante's "Purgatorio," it is chanted by spirits on the terrace of lust as part of their penitential process, reflecting their struggles with desire and chastity.

Top of page