Dante's Divine Comedy: Inferno

Canto XXXIV

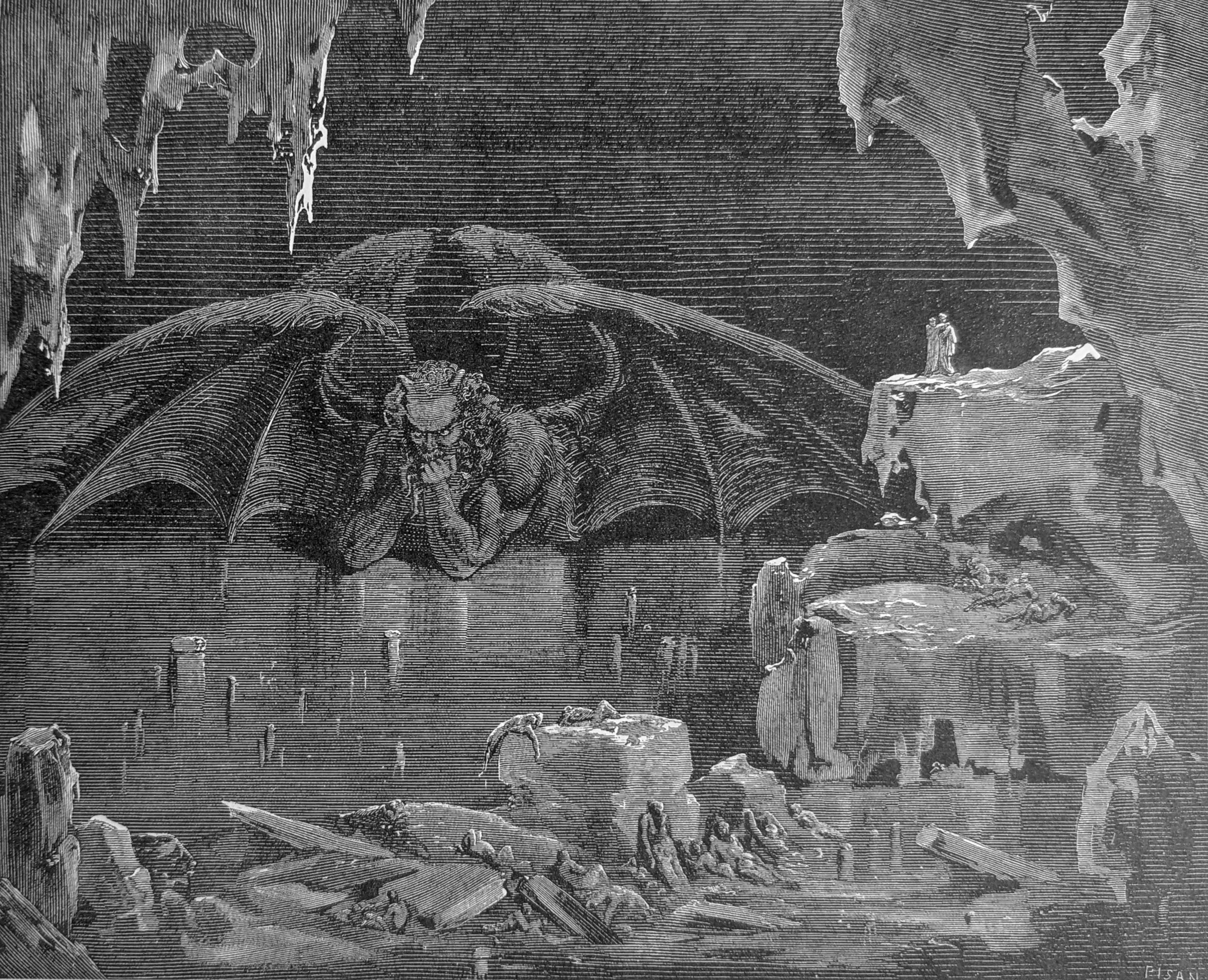

Across the lake can be glimpsed the shape of Lucifer like a windmill through the distant fog. The impotent creature stands alone in Judecca, the fourth division, immobile from the chest down, flapping his wings, each of his three faces chewing one of humankind's worst sinners - Judas Iscariot, who betrayed Christ, and Brutus and Cassius, joint conspirators against Caesar. Virgil carries Dante in piggyback fashion as they climb down Lucifer's back and thighs. Having passed through the center of the Earth, they struggle back up to a cave where a path will lead them to the safety of Mount Purgatory.

"Vexilla Regis prodeunt Inferni'

Towards us; therefore look in front of thee,'

My Master said, "if thou discernest him."[1]

As, when there breathes a heavy fog, or when

Our hemisphere is darkening into night,

Appears far off a mill the wind is turning,

Methought that such a building then I saw;

And, for the wind, I drew myself behind

My Guide, because there was no other shelter.

Now was I, and with fear in verse I put it,

There where the shades were wholly covered up,

And glimmered through like unto straws in glass.

Some prone are lying, others stand erect,

This with the head, and that one with the soles;

Another, bow-like, face to feet inverts.

When in advance so far we had proceeded,

That it my Master pleased to show to me

The creature who once had the beauteous semblance,

He from before me moved and made me stop,

Saying: "Behold Dis, and behold the place

Where thou with fortitude must arm thyself."

How frozen I became and powerless then,

Ask it not, Reader, for I write it not,

Because all language would be insufficient.

I did not die, and I alive remained not;

Think for thyself now, hast thou aught of wit,

What I became, being of both deprived.

The Emperor of the kingdom dolorous

From his mid-breast forth issued from the ice;

And better with a giant I compare

Than do the giants with those arms of his;

Consider now how great must be that whole,

Which unto such a part conforms itself.[2]

Were he as fair once, as he now is foul,

And lifted up his brow against his Maker,

Well may proceed from him all tribulation.

O, what a marvel it appeared to me,

When I beheld three faces on his head!

The one in front, and that vermilion was;[3]

Two were the others, that were joined with this

Above the middle part of either shoulder,

And they were joined together at the crest;

And the right-hand one seemed 'twixt white and yellow;

The left was such to look upon as those

Who come from where the Nile falls valley-ward.

Underneath each came forth two mighty wings,

Such as befitting were so great a bird;

Sails of the sea I never saw so large.

No feathers had they, but as of a bat

Their fashion was, and he was waving them,

So that three winds proceeded forth therefrom.

Thereby Cocy wholly was congealed

With six eyes did he weep, and down three chins

Trickled the tear-drops and the bloody drivel.[4]

At every mouth he with his teeth was crunching

A sinner, in the manner of a brake,

So that he three of them tormented thus

To him in front the biting was as naught

Unto the clawing, for sometimes the spine

Utterly stripped of all the skin remained.

"That soul up there which has the greatest pain,"

The Master said, "is Judas Iscariot,

With head inside, he plies his legs without.

Of the two others, who head downward are,

The one who hangs from the black jowl is Brutus,

See how he writhes himself, and speaks no word.[5]

And the other, who so stalwart seems, is Cassius.

But night is reascending, and 'tis time

That we depart, for we have seen the whole."

As seemed him good, I clasped him round the neck,

And he the vantage seized of time and place,

And when the wings were opened wide apart,

He laid fast hold upon the shaggy sides;

From fell to fell descended downward then

Between the thick hair and the frozen crust.

When we were come to where the thigh revolves

Exactly on the thickness of the haunch,

The Guide, with labor and with hard-drawn breath,

Turned round his head where he had had his legs,

And grappled to the hair, as one who mounts,

So that to Hell I thought we were returning.

"Keep fast thy hold, for by such stairs as these,"

The Master said, panting as one fatigued,

"Must we perforce depart from so much evil."

Then through the opening of a rock he issued,

And down upon the margin seated me;

Then tow'rds me he outstretched his wary step.

I lifted up mine eyes and thought to see

Lucifer in the same way I had left him;

And I beheld him upward hold his legs.

And if I then became disquieted,

Let stolid people think who do not see

What the point is beyond which I had passed.

"Rise up," the Master said, "upon thy feet;

The way is long, and difficult the road,

And now the sun to middle-tierce returns."

It was not any palace corridor

There where we were, but dungeon natural,

With floor uneven and unease of light.

"Ere from the abyss I tear myself away,

My Master," said I when I had arisen,

"To draw me from an error speak a little;

Where is the ice? and how is this one fixed

Thus upside down? and how in such short time

From eve to morn has the sun made his transit?"

And he to me: "Thou still imaginest

Thou art beyond the center, where I grasped

The hair of the fell worm, who mines the world.

That side thou wast, so long as I descended;

When round I turned me, thou didst pass the point

To which things heavy draw from every side,

And now beneath the hemisphere art come

Opposite that which overhangs the vast

Dry-land, and 'neath whose cope was put to death

The Man who without sin was born and lived.

Thou hast thy feet upon the little sphere

Which makes the other face of the Judecca.

Here it is morn when it is evening there;

And he who with his hair a stairway made us

Still fixed remaineth as he was before.

Upon this side he fell down out of heaven;

And all the land, that whilom here emerged,

For fear of him made of the sea a veil,

And came to our hemisphere; and peradventure

To flee from him, what on this side appears

Left the place vacant here, and back recoiled."[6]

A place there is below, from Beelzebub

As far receding as the tomb extends,

Which not by sight is known, but by the sound[7]

Of a small rivulet, that there descendeth

Through chasm within the stone, which it has gnawed

With course that winds about and slightly falls.

The Guide and I into that hidden road

Now entered, to return to the bright world;

And without care of having any rest

We mounted up, he first and I the second,

Till I beheld through a round aperture

Some of the beauteous things that Heaven doth bear;[8]

Thence we came forth to rebehold the stars.

Illustrations

"Behold Dis, and behold the place / Where thou with fortitude must arm thyself." Inf. XXXIV, lines 20-21

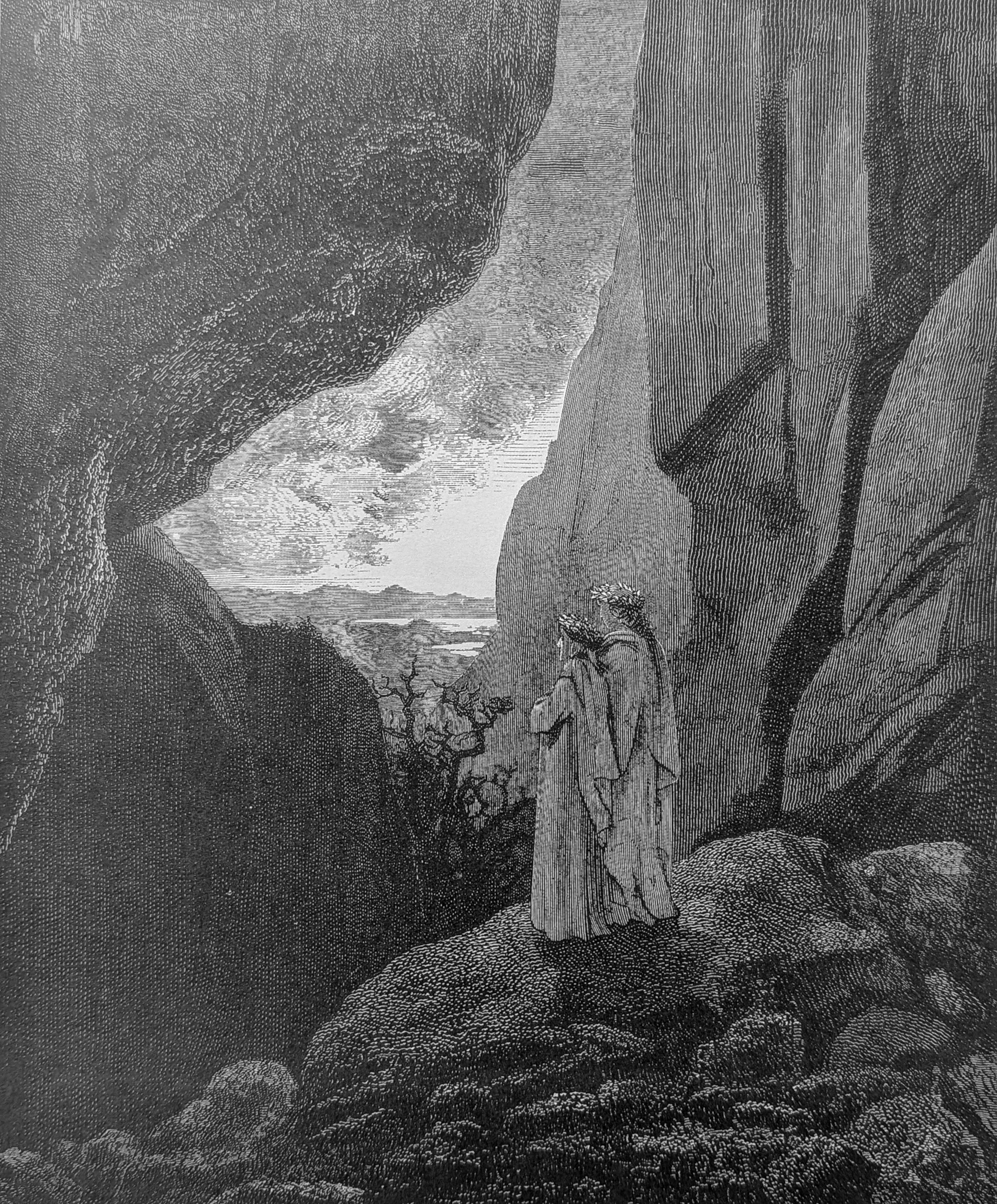

The Gasic and in that hidden road/Now entered, to return to the bright world; EXCUs 135-194

Thence we came forth to rebehold the stars. Inf. XXXIV, line 139

Footnotes

1. Dante begins this final canto of his Inferno in an almost blasphemous (but purposeful) way by inserting the word Inferni (Hell) into the first line of an ancient and famous Christian processional hymn, Vexila regis prodeunt, “The banners of the King come forth”. It was written in 569 by St. Venantius Fortunatus, Bishop of Potiers, France to celebrate the arrival in that city of a relic of the True Cross of Jesus sent by the Byzantine Emperor Justin II from Constantinople. After its first use as a processional hymn honoring the arrival of the sacred relic, it became embedded in the Christian liturgical rituals of Holy Week (the week before Easter), particularly on Good Friday well into the 20th century. Bear in mind that the journey through the Inferno began on the night before Good Friday (the evening of Holy Thursday when the Last Supper of Jesus with his disciples is commemorated), and the two travelers will emerge onto the Mountain of Purgatory at dawn on Easter Sunday morning. It should also be noted that the Vexilla regis is sung during the Church’s evening prayer, Vespers, on the Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, celebrated every year on September 14 – coincidentally the date of Dante’s death in 1321.

2. In Canto 31, the Giants were, in a sense, a prefigurement of their “king” whom Dante now stands before. And as Dante attempts to get a sense of Lucifer’s size, the reader will recall his doing the same thing when he encountered the Giants. This has led to some fascinating estimations. Lucifer’s arms alone are as long as the Giants are tall. And, while there is (purposely) insufficient numerical data to get an exact height, those who have tried have ranged from nearly 1,400 feet to about 4,000! The point here is that Lucifer is an immense creature compared to Dante and Virgil who, we must recall, only see the top third of him because they are standing on the ice which covers him up to his mid-chest.

3. Standing in the ice at chest-level, Lucifer calls to mind Farinata in Canto 10 who proudly stood in his great flaming tomb, visible from the waist up. Once again, Dante is taken aback by what is nothing less than a grotesque parody of the Holy Trinity: Lucifer has one head, but he has three faces—each one a different color. Over the centuries, commentators have suggested various interpretations for the colors. Some suggest that they stand for skin colors and therefore represent how sin and evil can be found among all the peoples of the world. Sayers and several others see the colors symbolically, suggesting that they represent the opposite qualities manifested in the Trinity: black stands for ignorance in the face of highest Wisdom, yellow stands for impotence in the face of divine Power, and red stands for hate in the face of primal Love. (With these terms in mind, recall the writing above the Gate of Hell at the beginning of Canto 3.) There are also political interpretations: Lord Vernon sees black representing Florence as the seat of the Black Guelps, yellow representing the lilies on the flag of France and red representing Rome as the seat of the Guelphs. Others give us even more contrasts with Lucifer himself: Light vs darkness, Truth vs lies, Life vs death, Joy vs woe, Kindness vs cruelty, Mercy vs wrath. Dante, of course, was surrounded by famous Medieval images of Last Judgments, and scenes of devils and sinners in Hell, and they must have given his imagination much to work on in this canto.

It is important to note, however, that Lucifer does not have three heads. That would be inconsistent with the theology being parodied. Instead, he has three complete anatomical faces attached to each other—a central face colored red, on Lucifer’s right is the yellow face, and on his left is the black face. The side faces appear to grow out of the shoulders, somewhat farther onto the shoulder than the central face—perhaps growing out of the far right and far left sides of the central face. But that head is all of a piece, with the three heads coming together at the crown.

4. But Dante immediately brings us back to the parody by telling us that those wings – immense as they were—looked like bats’ wings! His wings seem to be the only angelic characteristic Lucifer has left, but even they are made horrid. And worse, he never stops flapping them. He’s like a great bird that is trapped. Stuck in the ice of Cocytus as he is, and trying with all his might to escape, he weeps in a rage of frustration, and his tears trap him all the more as he freezes them with his incessant flapping. Dumb as he now is, he might otherwise realize that if he stood still, the ice that entraps him would melt! E.H. Plumptre catches the symbolism here: “The bat is, perhaps, chosen as the emblem of the will that loves darkness rather than light, because its deeds are evil.” And with his three sets of wings, Lucifer creates three winds. Again, we can see the Trinitarian parody at work even here. In the Bible, wind is often a symbol for the creative activity of God. Here it simply keeps things as they are—forever.

5. Here, Dante names the three sinners being chewed and mangled in Lucifer’s mouths. The sinner whom he described as getting the worst of the chewing is head-first inside the central mouth. This is Judas Iscariot, the one who betrayed Jesus. That he is in this “hole” upside down and kicking reminds us of the Simonists in Canto 19, particularly the papal simonists who betrayed the Church by their lack of fidelity to the Gospel. Furthermore, considering how Judas betrayed Jesus, the head of the Apostles and the Church, with a kiss, it’s greatly ironic to see him in the central mouth of Lucifer. The other two, punished less fiercely than Judas, are feet-first in the left and right mouths—Brutus and Cassius, the betrayers and assassins of Julius Caesar. They appear to be hanging down out of each mouth. The one in the black mouth is Marcus Junius Brutus, and the one in the yellow mouth is Caius Cassius Longinus.

Because the Commedia is a Christian poem, one might well understand why Judas is in Lucifer’s mouth. But why Brutus and Cassius? In Dante’s view, the world was ideally governed by the Church (the heavenly Rome) and the Empire (the earthly Rome), ruled respectively by the Pope and the Emperor. When these two rulers ruled in harmony, there was peace. But, as he will show us throughout the Poem, the two rulers often attempt to supplant one another or to take on the other’s role, resulting in chaos and disorder in both realms. Brutus and Cassius, by their part in the death of Caesar, the head of the empire, created disorder in the empire. Their hanging out of the mouths upside down symbolizes this.

6. Just before they began their descent down the side of Lucifer, Virgil told Dante, “Soon it will be night.” It is generally assumed that he meant around 6:00 pm in the evening. We don’t know from the text, however, how long it took them to reach the other side of the ice where they have been sitting since they got themselves off of Lucifer’s hip. But Virgil once again tells Dante the time—around 7:00 am in the morning, and about 12 hours since they began their descent on Lucifer. During that 12 hours they’ve gone from night to day. And notice that this time reference is no longer given by references to the night or the moon as they have been all through the Inferno. This sunlit reference indicates that they have crossed from the northern hemisphere to the southern, and from now on in the poem time will be told with reference to the sun (which always represents God and the light of God).

7. Ba'al Zabub , Ba'al Zvuv or Beelzebub, known as the Lord of the Flies, is a name derived from a Philistine god, formerly worshipped in Ekron, and later adopted by some Abrahamic religions as a major demon. Among Christians, Beelzebub is another name for Satan.

8. Looking back for a moment, Dante and Virgil are standing in a great dungeon on the other side of Judecca, with Lucifer’s legs pointing upward far above them. Dante refers to this as Lucifer’s tomba, his tomb (which, of course, he dug for himself!). However, beyond this dungeon is a long tunnel which most likely marks the path through which Lucifer bored through the earth from the south. Through this tunnel runs a stream that originates at the Mountain of Purgatory above them. Virgil notes that though its waters can’t be seen, they can hear it flowing. Though Dante does not name this stream, virtually every commentator notes that this is the Lethe—the waters of forgetfulness of sin and evil which flows down from the very top of the Mountain of Purgatory. It flows down to join the Acheron, the Phlegethon, and the Styx to form the ice of Cocytus, carrying with it to Lucifer all the sin and wickedness purged from the souls in Purgatory. Though Dante does not state this precisely, at the end of Canto 14, he asks Virgil whether they’ll see the river Lethe. Virgil tells him that he won’t see it in Hell but beyond, where souls wash themselves of their sins and guilt (ll 130-138).

Top of page