Dante's Divine Comedy: Inferno

Canto XIX

Crossing the bridge into the third bolgia, Virgil and Dante enter a landscape full of holes from which protrude the flaming, flailing legs of the Simonists. In life, these fraudulent ecclesiastics profited from the Church and its offices. Dante questions a pair of legs and discovers they belong to Pope Nicholas III, who mistakes him for Boniface VIII, the next pope destined to fall down that hole. According to the Simonist's eloquent prophecy, Pope Clement V is third in line. Dante expresses his moral indignation in equally ornate language. Virgil rewards his progress by carrying him to the arch above the fourth bolgia.

O Simon Magus, O forlorn disciples,

Ye who the things of God, which ought to be

The brides of holiness, rapaciously[1]

For silver and for gold do prostitute,

Now it behooves for you the trumpet sound,

Because in this third _Bolgia_ ye abide.

We had already on the following tomb

Ascended to that portion of the crag

Which o'er the middle of the moat hangs plumb.

Wisdom supreme, O how great art thou showest

In heaven, in Earth, and in the evil world,

And with what justice doth thy power distribute!

I saw upon the sides and on the bottom

The livid stone with perforations filled,

All of one size, and every one was round.

To me less ample seemed they not, nor greater

Than those that in my beautiful Saint John

Are fashioned for the place of the baptizers,[2]

And one of which, not many years ago,

I broke for some one, who was drowning in it;

Be this a seal all men to undeceive.

Out of the mouth of each one there protruded

The feet of a transgressor, and the legs

Up to the calf, the rest within remained.

In all of them the soles were both on fire;

Wherefore the joints so violently quivered,

They would have snapped asunder withes and bands.

Even as the flame of unctuous things is wont

To move upon the outer surface only,

So likewise was it there from heel to point.

"Master, who is that one who writhes himself,

More than his other comrades quivering,"

I said, "and whom a redder flame is sucking?"

And he to me: "If thou wilt have me bear thee

Down there along that bank which lowest lies,

From him thou'lt know his errors and himself."

And I: "What pleases thee, to me is pleasing;

Thou art my Lord, and knowest that I depart not

From thy desire, and knowest what is not spoken."

Straightway upon the fourth dike we arrived;

We turned, and on the left-hand side descended

Down to the bottom full of holes and narrow.

And the good Master yet from off his haunch

Deposed me not, till to the hole he brought me

Of him who so lamented with his shanks.

"Whoe'er thou art, that standest upside down,

O doleful soul, implanted like a stake,"

To say began I, "if thou canst, speak out."

I stood even as the friar who is confessing

The false assassin, who, when he is fixed,

Recalls him, so that death may be delayed.

And he cried out: "Dost thou stand there already,

Dost thou stand there already, Boniface?

By many years the record lied to me.[3]

Art thou so early satiate with that wealth,

For which thou didst not fear to take by fraud

The beautiful Lady, and then work her woe?"

Such I became, as people are who stand,

Not comprehending what is answered them,

As if bemocked, and know not how to answer.

Then said Virgilius: "Say to him straightway,

'I am not he, I am not he thou thinkest.' "

And I replied as was imposed on me.

Whereat the spirit writhed with both his feet,

Then, sighing, with a voice of lamentation

Said to me: "Then what wantest thou of me?

If who I am thou carest so much to know,

That thou on that account hast crossed the bank,

Know that I vested was with the great mantle;

And truly was I son of the She-bear,

So eager to advance the cubs, that wealth

Above, and here myself, I pocketed.

Beneath my head the others are dragged down

Who have preceded me in simony,

Flattened along the fissure of the rock.

Below there I shall likewise fall, whenever

That one shall come who I believed thou wast,

What time the sudden question I proposed.

But longer I my feet already toast,

And here have been in this way upside down,

Than he will planted stay with reddened feet;

For after him shall come of fouler deed

From tow'rds the west a Pastor without law,

Such as befits to cover him and me.

New Jason will he be, of whom we read

In Maccabees; and as his king was pliant,

So he who governs France shall be to this one."[4]

I do not know if I were here too bold,

That him I answered only in this meter:

"I pray thee tell me now how great a treasure

Our Lord demanded of Saint Peter first,

Before he put the keys into his keeping?

Truly he nothing asked but 'Follow me.'

Nor Peter nor the rest asked of Matthias

Silver or gold, when he by lot was chosen

Unto the place the guilty soul had lost.[5]

Therefore stay here, for thou art justly punished,

And keep safe guard o'er the ill-gotten money,

Which caused thee to be valiant against Charles.[6]

And were it not that still forbids it me

The reverence for the keys superlative

Thou hadst in keeping in the gladsome life,

I would make use of words more grievous still;

Because your avarice afflicts the world,

Trampling the good and lifting the depraved.

The Evangelist you Pastors had in mind,

When she who sitteth upon many waters

To fornicate with kings by him was seen;

The same who with the seven heads was born,

And power and strength from the ten horns received,

So long as virtue to her spouse was pleasing.

Ye have made yourselves a god of gold and silver;

And from the idolater how differ ye,

Save that he one, and ye a hundred worship?

Ah, Constantine! of how much ill was mother,

Not thy conversion, but that marriage dower

Which the first wealthy Father took from thee!"[7]

And while I sang to him such notes as these,

Either that anger or that conscience stung him,

He struggled violently with both his feet.

I think in sooth that it my Leader pleased,

With such contented lip he listened ever

Unto the sound of the true words expressed.

Therefore with both his arms he took me up,

And when he had me all upon his breast,

Remounted by the way where he descended.

Nor did he tire to have me clasped to him;

But bore me to the summit of the arch

Which from the fourth dike to the fifth is passage.

There tenderly he laid his burden down,

Tenderly on the crag uneven and steep,

That would have been hard passage for the goats:

Thence was unveiled to me another valley.

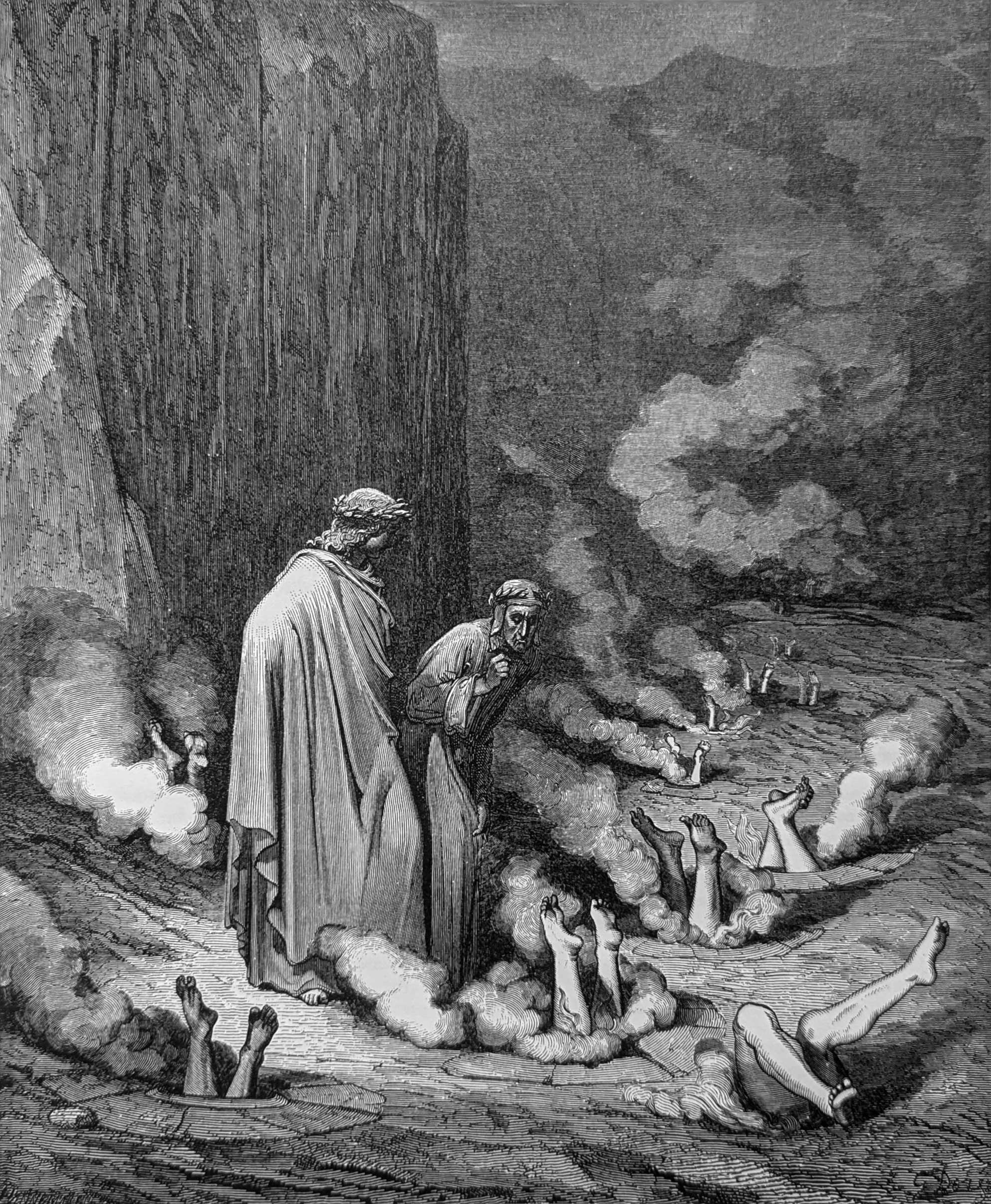

Illustration

"O doleful soul, implanted like a stake," / To say began I, "if thou canst, speak out." Inf. XIX, lines 47-48

Footnotes

1. Simon Magus was a magician who appears in chapter 8 of the Acts of the Apostles. As a Christian convert baptized by Philip, he had apparently seen the power of the Holy Spirit come upon those who were later baptized by Peter and John. He offered them money if they would sell him that power. Instead, Peter severely denounced him and sent him away to pray that God would forgive him for such a presumption. In fact, that is what Simon did, and the story ends with him asking Peter to pray for him that he might be forgiven. Magicians, sorcerers, and astrologers were common in the ancient world, and this story most likely finds its way into New Testament as a challenge to those who attempt to fool others into believing that they, too, worked wonders through the power of God. In the end, Simon Magus gets a bad rap, but ever afterward, the crime/sin of buying and selling the holy things of the Church, including positions of power and influence, has been called "simony" after him. No doubt, one can get a sense of how this sin afflicted the Church in Dante's time from his manner of expression here, but one can only imagine the Poet's horror had he lived at the time of the Protestant Reformation and saw the damage such a sin caused then and into the future. punishment of the sinners - will lead forward and further mito the carico. Tes being led by his words.

2. St. John the Baptist.

3. This is one of the boldest, most cleverly devised, and most unexpected questions in the entire poem. One can only imagine the response of Dante's original readers - from shock to outright laughter to violent anger. The almost casual question, "Are you here so soon, Boniface?" was not the expected answer to Dante's "make some noise...if you can." The speaker as we will learn almost immediately is a recent predecessor of Pope Boniface VIII, Nicholas III. The pontificate of Boniface spanned the years 1294-1303, and he would have been alive during the time when Dante sets his poem. Recall from Canto 18 that it was Boniface who began the Jubilee Year in Rome in 1300. Has Dante made a mistake here? No, he doesn't put living people in Hell. Instead, it's the speaker's "mistake" in naming a living person, though if we understand the spirits to have some kind of foreknowledge, he foresaw that his successor would follow him. Nevertheless, it was Boniface's meddling in the civic and political affairs of Florence that led to Dante's exile in 1302. The words Dante puts in Nicholas' mouth speak for themselves. Apart from the simony, to have "ravished Holy Mother Church" and then to have torn her to pieces, did not make Boniface a popular or a saintly Pope. Nicholas III, notably worse than Boniface, was, in fact, followed by a Saint, Pope Celestine V. But this aged monk did not want the papacy and resigned after just five months. Boniface is reputed to have browbeat the poor man until he resigned- and then is said to have harassed and persecuted him until he died a short time later. Many commentators suggest it is this pope who is referred to early in Canto 3 as the one who made "the great refusal," namely, his abdication of the papacy. There is no hard evidence that put this poor old monk in Hell, except that it may be Dante's symbolic way of saying that his abdication led immediately to the election of Boniface and all of his corruption.

4. To heighten the effect, if two simoniac popes are not enough for Dante, Nicholas foretells that one worse than he and Boniface will soon arrive and shove both of them further down into their hole. This passage is a reference to Clement V, who was Pope from 1305 to 1314. He was from Gascony, a province in the southwestern part of France, thus the reference to his coming "from the west." Noted for his greed and lust, he was a puppet of King Philip IV (the Fair) to whom he owed his election as pope. In 1309, he moved the papacy from Rome to Avignon in southeastern France, and thus began what is known in history as the "Avignon Papacy" and the "Babylonian Captivity" of the Church which lasted until 1377. He is also noted for conspiring with Philip in the suppression of the Knights Templar. As disdainful as he may have been at referring to Scripture, Nicholas does so in making an oblique comparison of Clement to the evil High Priest Jason in the Second Book of Maccabees. This is a story of simony on a large scale before it came to be called that. Chapter 4: 7-17 tells of how Jason depraved the High Priesthood and shocked the Jews of his time. The comparisons with Clement are appropriate.

5. The shy Dante has found his voice, and this is just the beginning! This is another case of reversal in this canto. One could imagine the words in this scene to be spoken by a cleric with a solid theological education to a hardened sinner. But Dante also has a solid theological education, and here, as a layman, it is he who excoriates the sinner—this man who held the highest office in the Church! The degradation of the papacy was a wound Dante bore all his life. His ideal of the balance between the kingdom o f this world and the kingdom of heaven—the empire and the Church was constantly shattered by bad rulers in both kingdoms. Having now met one of the worst rulers of the Church, the hesitant Pilgrim blasts Nicholas and his kind with searing truth. If the wicked pope’s feet were on fire, surely the rest of him burned as Dante forcefully rebuked him. As noted earlier, one could imagine how demoralized Dante would have been had he lived at the start of the Protestant Reformation . But standing here at this “Hole of Popes,” could he, one wonders, in his wildest dreams have imagined the Borgias?

The two examples Dante notes are from the New Testament. The first is from Matthew 16:18 where Jesus figuratively bestows the “keys” to the Kingdom of Heaven on Peter who has rightly identified him as the Messiah. The second example comes from t he first chapter of the Acts of the Apostles where the Apostles select an honorable successor to Judas who betrayed Jesus. No money changed hands in either story.

6. Here, Dante inserts another historical reference to validate not only that Nicholas was a greedy simonist but that he was involved in numerous political intrigues, this, perhaps, being the worst one. Charles of Anjou was the seventh son of King Louis VIII o f France. His oldest brother succeeded his father as King Louis IX and was canonized a Saint in 1297 by Pope Boniface VIII (ironic in itself, that such a just and upright ruler should be canonized by such a wicked pope!). Charles became king of Naples and S icily and enjoyed the favor of several popes, but Nicholas abandoned him after the king refused to allow one of his nephews to marry the pope’s niece. Charles let it be known that such an alliance was far beneath him. Later, it seems—though this is most likely a legend in light of modern historical scholarship—Nicholas was involved in a scheme against Charles that included the Emperor of Greece, Michael Palaeologus, paying the pope to support a rebellion which ended in the famous massacre known as the “Sicilian Vespers” where, in 1282, the Sicilians overthrew the yoke of French rule. By the time this massacre actually occurred, Nicholas had been dead for two years, though it was commonly believed (by Dante, as well) that he was involved in the plot for some time before his death in 1280.

7. With this final apostrophe, Dante brings his tirade against Pope Nicholas III and other simoniacal popes to an end. And this statement contains much fascinating information. Dante’s mention of Constantine here is not so much to blame him or implicate him in the sin of simony. Rather, this is a kind of shorthand that appears in front of a long and fascinating story. The Emperor Constantine reigned from 306-337, was converted to Christianity in the year 312, but only shortly before his death was he finally baptized. Having conquered much of the eastern Mediterranean, he transferred the seat of the Empire from Rome to Byzantium—later known as Constantinople and presently as Istanbul—in 330.

In Dante’s day, there was already a tradition/legend that the Emperor contracted leprosy while still reigning in Rome. Despite every effort to find a cure, nothing could be done to stop the spread of the disease. When all seemed hopeless, Constantine apparently had a vision of Saints Peter and Paul who urged him to seek the aid of Pope Sylvester I. The pope responded to the Emperor’s summons, teaching him the rudiments of the faith and then baptizing him. During his baptism, Constantine the leper was miraculously cured of his disease. The “Donation” is a reference to the Donation of Constantine. This document (see below), purportedly composed by Constantine, was most likely written in the eighth century. In it he places (donates) the city of Rome, all of Italy , and a sizable portion of the western half of his empire, along with spiritual and temporal power over the same—not to mention authority over the universal Church—into the hands of the papacy as a perpetual thank-offering for his cure by Pope Sylvester.

In 1439, a Renaissance priest and scholar, Lorenzo Valla, proved that the document was a forgery. Nevertheless, its importance cannot be overestimated during the centuries it was considered to be valid, especially when one considers the history of the papacy in relation to western Europe during that thousand-year period. Dante’s reference to “that first wealthy pope,” is Sylvester, of course, but in reality it marks off an epoch – certainly by Dante’s time – that saw the increasing wealth and power of the papacy where some popes were almost indistinguishable from secular rulers. Undoubtedly, Dante believed in the validity of the “Donation,” but, as he has already noted in the Poem, and will continue to do so, almost to the end, he saw it as a corrosive influence that ruined with avarice and greed the Shepherds who were ordained to lead and protect the flock of Christ.

Top of page