Dante's Divine Comedy: Inferno

Canto VII

At Virgil's behest, Plutus, god of material wealth, dissipates into thin air between the Third and Fourth Circles. The poets watch the noisy Hoarders and the Spendthrifts rolling huge weights at one another. After discussing Fortune's distribution of temporal riches, they reach the river Styx, the second of Hell's rivers, which is the Fifth Circle. Here are mired the Wrathful, who tear at one another, and the Sluggish, who doze beneath the slime. Dante and Virgil come to the foot of a high tower.

"Pape Satan, Pape Satan, Aleppe!"

Thus Plutus with his clucking voice began;

And that benignant Sage, who all things knew,[1]

Said, to encourage me: "Let not thy fear

Harm thee; for any power that he may have

Shall not prevent thy going down this crag."

Then he turned round unto that bloated lip,

And said: "Be silent, thou accursed wolf;

Consume within thyself with thine own rage.

Not causeless is this journey to the abyss;

Thus is it willed on high, where Michael wrought

Vengeance upon the proud adultery."[2]

Even as the sails inflated by the wind

Involved together fall when snaps the mast,

So fell the cruel monster to the earth.

Thus we descended into the fourth chasm,

Gaining still farther on the dolesome shore

Which all the woe of the universe insacks.

Justice of God, ah! who heaps up so many

New toils and sufferings as I beheld?

And why doth our transgression waste us so?

As doth the billow there upon Charybdis,

That breaks itself on that which it encounters,

So here the folk must dance their roundelay.[3]

Here saw I people, more than elsewhere, many,

On one side and the other, with great howls,

Rolling weights forward by main force of chest.

They clashed together, and then at that point

Each one turned backward, rolling retrograde,

Crying, "Why keepest?" and, "Why squanderest thou?"

Thus they returned along the lurid circle

On either hand unto the opposite point,

Shouting their shameful meter evermore.

Then each, when he arrived there, wheeled about

Through his half-circle to another joust;

And I, who had my heart pierced as it were,

Exclaimed: "My Master, now declare to me

What people these are, and if all were clerks,

These shaven crowns upon the left of us.”

And he to me: "All of them were asquint

In intellect in the first life, so much

That there with measure they no spending made.

Clearly enough their voices bark it forth,

Whene'er they reach the two points of the circle,

Where sunders them the opposite defect.

Clerks those were who no hairy covering

Have on the head, and Popes and Cardinals,

In whom doth Avarice practice its excess."[4]

And I: "My Master, among such as these

I ought forsooth to recognize some few,

Who were infected with these maladies."

And he to me: "Vain thought thou entertainest;

The undiscerning life which made them sordid

Now makes them unto all discernment dim.

Forever shall they come to these two buttings;

These from the sepulchre shall rise again

With the fist closed, and these with tresses shorn.

Ill giving and ill keeping the fair world

Have ta'en from them, and placed them in this scuffle;

Whate'er it be, no words adorn I for it.

Now canst thou, Son, behold the transient farce

Of goods that are committed unto Fortune,

For which the human race each other buffet;[5]

For all the gold that is beneath the moon,

Or ever has been, of these weary souls

Could never make a single one repose."

"Master," I said to him, "now tell me also

What is this Fortune which thou speakest of,

That has the world's goods so within its clutches?"

And he to me: "O creatures imbecile,

What ignorance is this which doth beset you?

Now will I have thee learn my judgment of her.

He whose omniscience everything transcends

The heavens created, and gave who should guide them,

That every part to every part may shine,

Distributing the light in equal measure;

He in like manner to the mundane splendors

Ordained a general ministress and guide,

That she might change at times the empty treasures

From race to race, from one blood to another,

Beyond resistance of all human wisdom.

Therefore one people triumphs, and another

Languishes, in pursuance of her judgment,

Which hidden is, as in the grass a serpent.

Your knowledge has no counter-stand against her,

She makes provision, judges, and pursues

Her governance, as theirs the other gods.

Her permutations have not any truce;

Necessity makes her precipitate,

So often cometh who his turn obtains.

And this is she who is so crucified

Even by those who ought to give her praise,

Giving her blame amiss, and bad repute.

But she is blissful, and she hears it not;

Among the other primal creatures gladsome

She turns her sphere, and blissful she rejoices.

Let us descend now unto greater woe;

in this scuffle; Already sinks each star that was ascending

When I set out, and loitering is forbidden."

We crossed the circle to the other bank,

Near to a fount that boils, and pours itself

Along a gully that runs out of it.

The water was more somber far than perse;

And we, in company with the dusky waves,

Made entrance downward by a path uncouth.

A marsh it makes, which has the name of Styx,

This tristful brooklet, when it has descended

Down to the foot of the malign gray shores.[6]

And I, who stood intent upon beholding,

Saw people mud-besprent in that lagoon,

All of them naked and with angry look.

They smote each other not alone with hands,

But with the head and with the breast and feet,

Tearing each other piecemeal with their teeth.

Said the good Master: "Son, thou now beholdest

The souls of those whom anger overcame;

And likewise I would have thee know for certain

Beneath the water people are who sigh

And make this water bubble at the surface,

As the eye tells thee wheresoe'er it turns.

Fixed in the mire they say, 'We sullen were

In the sweet air, which by the sun is gladdened,

Bearing within ourselves the sluggish reek;

Now we are sullen in this sable mire.'

This hymn do they keep gurgling in their throats,

For with unbroken words they cannot say it."

Thus we went circling round the filthy fen

A great are 'twixt the dry bank and the swamp,

With eyes turned unto those who gorge the mire;

Unto the foot of a tower we came at last.

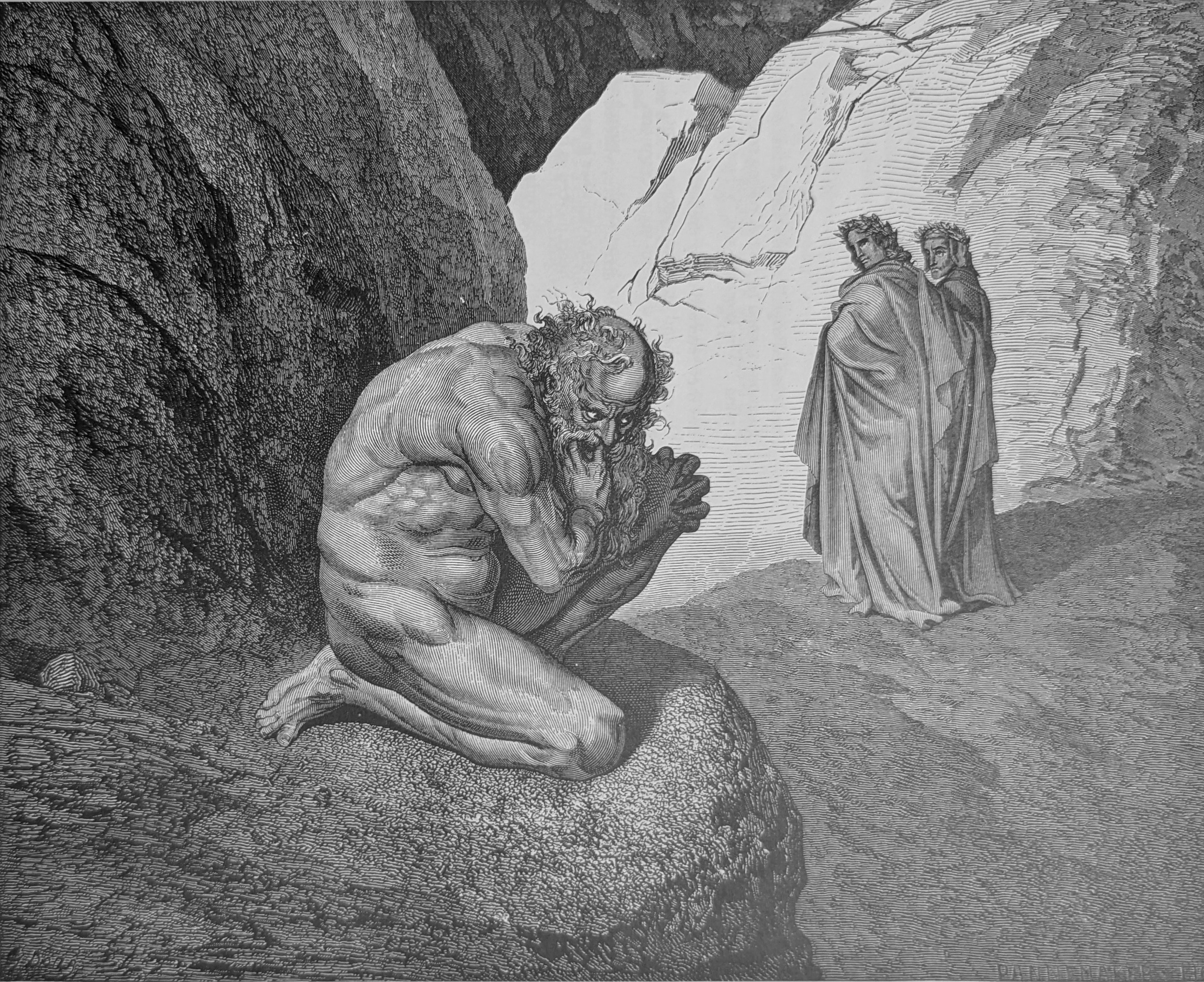

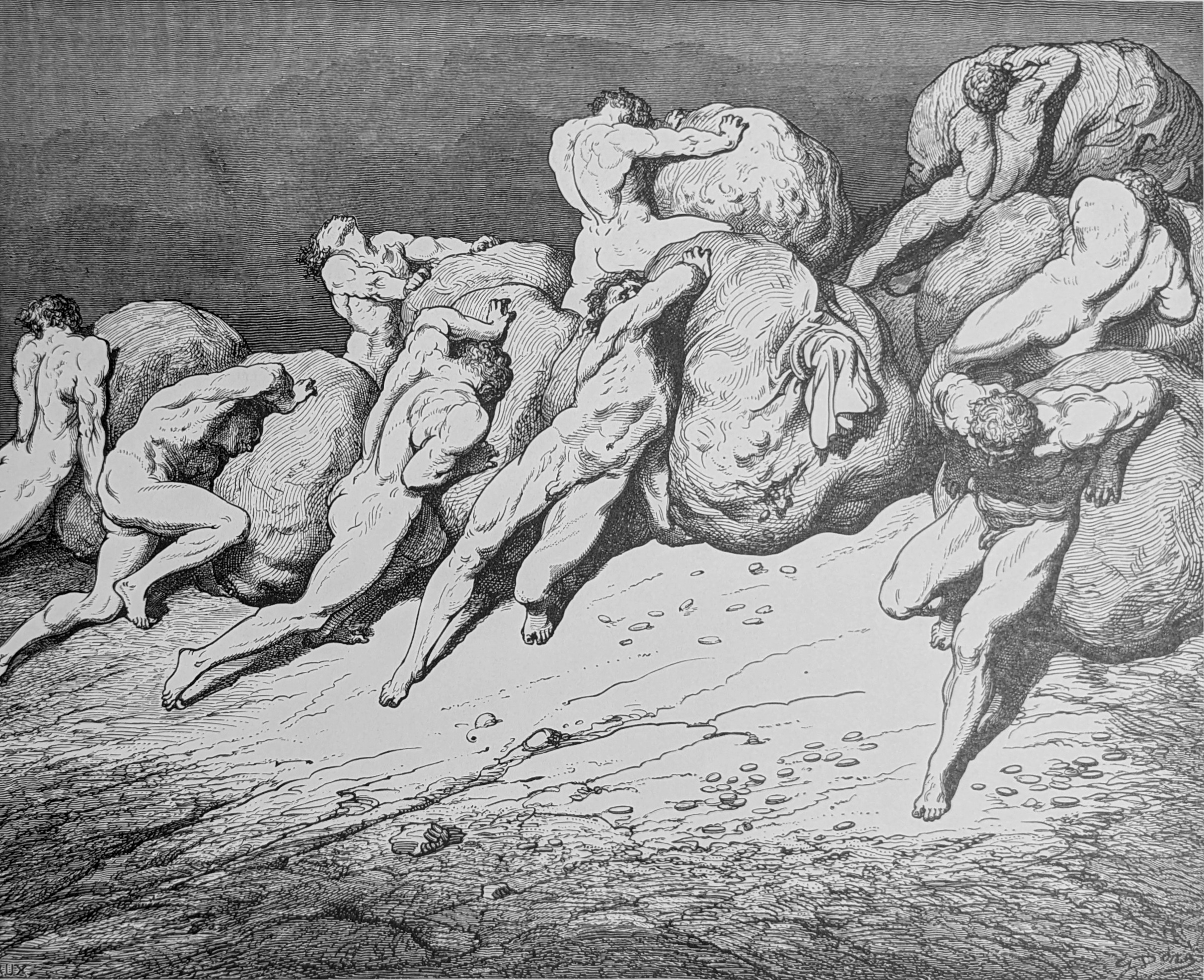

Illustrations

"Be silent, thou accursed wolf; / Consume within thyself with thine own rage." Inf. VII, lines 8-9

"For all the gold that is beneath the moon / Or ever has been, of these weary souls / Could never make a single one repose." Inf. VII, lines 64-66

"Son, thou now beholdest / The souls of those whom anger overcame;" Inf. VII, lines 115-116

Footnotes

1. Apart from the fact that these words are not Italian, that “pape” looks like the word “pope,” and “Satàn” looks like the word “Satan,” – draw your own conclusions – these words are gibberish and have confounded centuries of commentators. Nevertheless, they create a segue between the end of Canto 6 and the beginning of this one. We learned at the end of the previous canto that this was Pluto, and his wild expostulation here may be surprise or anger at seeing his region of Hell invaded by strangers. And we have here yet another mythological guardian of these infernal regions who objects to the presence of Dante and his guide. Recall Charon in Canto 3, Minos in Canto 5, and Cerberus in Canto 6.

2. Twice already, once to Charon in Canto 3 and once to Minos in Canto 5, Virgil has used a similar formula to secure their safe passage, though the inclusion of the Archangel Michael here is new.

3. The mention of Scylla and Charybdis is a reference to the Strait of Messina that separates the “toe” of Italy from Sicily. It is 20 miles long, at its northern end it is about 2 miles across, and at its southern end about 10 miles across. From the time boats started criss-crossing the Mediterranean, it has served as a convenient, but sometimes dangerous, shortcut between Italy and Sicily. Changing tides and currents, winds, whirlpools, and hidden rocks demand careful planning and navigation. In the ancient world, these dangers, which undoubtedly swallowed any number of ships, became personified in two terrifying monsters who lived at the northern and narrowest end of the strait: Charybdis becoming the whirlpool, and Scylla a great rock. Being “between a rock and a hard place” now makes sense. The monsters appear in Homer and in Virgil. Virgil writes this in his Aeneid (Book III:522-550):

“But when the wind carries you, on leaving, to the Sicilian shore, and the barriers of narrow Pelorus open ahead, make for the seas and land to port, in a long circuit: avoid the shore and waters on the starboard side. They say, when the two were one continuous stretch of land, they one day broke apart, torn by the force of a vast upheaval (time’s remote antiquity enables such great changes). The sea flowed between them with force, and severed the Italian from the Sicilian coast, and a narrow tideway washes the cities and fields on separate shores. Scylla holds the right side, implacable Charybdis the left, who, in the depths of the abyss, swallows the vast flood three times into the downward gulf and alternately lifts it to the air, and lashes the heavens with her waves. But a cave surrounds Scylla with dark hiding-places, and she thrusts her mouths out, and drags ships onto the rocks. Above she has human shape, and is a girl, with lovely breasts, a girl, down to her sex, below it she is a sea-monster of huge size, with dolphins’ tails joined to a belly formed of wolves. It is better to round the point of Pachynus, lingering, and circling Sicily on a long course, than to once catch sight of hideous Scylla in her vast cave and the rocks that echo to her sea-dark hounds.”

4. The various mentions of opposites – Scylla and Charybdis, misers and spenders, those on the right and those on the left – all point to the ever-present possibility of destruction and death when ships passed through the Strait of Messina (see note 6) – too far on either side led to doom. Safe passage was straight down the middle, the via media – prudence and generosity. But not here. As Virgil tells Dante, all the souls here had “narrow minds” and “no sense” about money. To add to overall effect of this scene, he verifies Dante’s suspicion that many of the souls condemned in this circle were clerics, even high Church officials, who were overcome by avarice. As will be seen throughout the poem, Dante the poet doesn’t hesitate to sternly rebuke members of the ecclesiastical establishment who scandalize the faithful by their sinful behavior.

5. The goddess of Fortune, a popular figure in the Middle Ages, is often depicted sitting next to a great turning wheel or holding a smaller one. This is the Wheel of Fortune or Chance. On the wheel are human figures who are seated toward the top, but as the wheel turns, they fall off. In Dante’s cosmology (which he borrows from Ptolemy), each of the heavenly spheres or planets has a special angelic guide who moves it. Here he tells us that God also created a guide of wealth, who is blessed and happy, and whose purpose is to move it around constantly and without care. Thus, as Virgil stated earlier, she “makes a great mockery” of people’s wealth.

6. If the word Styx means “hateful,” it is fitting for the souls here. Whether above the swamp or in the muck below, the anger among these souls rages uncontrollably. What’s worse, the savagery is indiscriminate. We are not told whether any of the souls knew each other in life and carry on their feuding here in the afterlife. In the depths of the muck, as Virgil tells Dante, the souls are literally incapacitated – drowned – by their anger in such sullenness and hatred for everything, including themselves, that all they can do is gurgle. As opposed to anger, sullenness is more inward and stifling, and so these souls are hidden below the surface of the swamp. And interestingly enough, these sullen sinners self-advertise in the “song” they gurgle perpetually.

Top of page