Dante's Divine Comedy: Inferno

Canto XXI

Virgil and Dante stand on the arch that spans the fifth bolgia. They see black devils running along it, with sinners over their shoulders which they cast into a ditch bubbling with pitch. These are Barrators, who sinned against the State and are now tormented by a company of pitchfork-wielding Malebranche devils. Dante bides while Virgil addresses their captain, Malacoda, declaring that Heaven wills him and another to pass. The devils exchange obscene parting salutes as a team of them escorts the poets to a different bridge (the sixth one lies broken).

From bridge to bridge thus, speaking other things

Of which my Comedy cares not to sing,

We came along, and held the summit, when

We halted to behold another fissure

Of Malebolge and other vain laments;

And I beheld it marvelously dark.[1]

As in the Arsenal of the Venetians

Boils in the winter the tenacious pitch

To smear their unsound vessels o'er again,[2]

For sail they cannot; and instead thereof

One makes his vessel new, and one recaulks

The ribs of that which many a voyage has made;

One hammers at the prow, one at the stern,

This one makes oars, and that one cordage twists,

Another mends the mainsail and the mizzen;

Thus, not by fire, but by the art divine,

Was boiling down below there a dense pitch

Which upon every side the bank belimed.

I saw it, but I did not see within it

Aught but the bubbles that the boiling raised,

And all swell up and resubside compressed.

The while below there fixedly I gazed,

My Leader, crying out: "Beware, beware!"

Drew me unto himself from where I stood.

Then I turned round, as one who is impatient

To see what it behooves him to escape,

And whom a sudden terror doth unman,

Who, while he looks, delays not his departure;

And I beheld behind us a black devil,

Running along upon the crag, approach.

Ah, how ferocious was he in his aspect!

And how he seemed to me in action ruthless,

With open wings and light upon his feet!

His shoulders, which sharp-pointed were and high,

A sinner did encumber with both haunches,

And he held clutched the sinews of the feet.

From off our bridge, he said: "O Malebranche,

Behold one of the elders of Saint Zita;

Plunge him beneath, for I return for others[3]

Unto that town, which is well furnished with them.

All there are barrators, except Bonturo;

No into Yes for money there is changed."[4]

He hurled him down, and over the hard crag

Turned round, and never was a mastiff loosened

In so much hurry to pursue a thief.

The other sank, and rose again face downward;

But the demons, under cover of the bridge,

Cried: "Here the Santo Volto has no place![5]

Here swims one otherwise than in the Serchio;

Therefore, if for our gaffs thou wishest not,

Do not uplift thyself above the pitch."

They seized him then with more than a hundred rakes;

They said: "It here behooves thee to dance covered,

That, if thou canst, thou secretly mayest pilfer."

Not otherwise the cooks their scullions make

Immerse into the middle of the cauldron

The meat with hooks, so that it may not float.

Said the good Master to me: "That it be not

Apparent thou art here, crouch thyself down

Behind a jag, that thou mayest have some screen;

And for no outrage that is done to me

Be thou afraid, because these things I know,

For once before was I in such a scuffle."

Then he passed on beyond the bridge's head,

And as upon the sixth bank he arrived,

Need was for him to have a steadfast front.

With the same fury, and the same uproar,

As dogs leap out upon a mendicant,

Who on a sudden begs, where'er he stops,[6]

They issued from beneath the little bridge,

And turned against him all their grappling-irons,

But he cried out: "Be none of you malignant!

Before those hooks of yours lay hold of me,

Let one of you step forward, who may hear

And then take counsel as to grappling me."

They all cried out: "Let Malacoda go;"

Whereat one started, and the rest stood still,

And he came to him, saying: "What avails it?"[7]

"Thinkest thou, Malacoda, to behold me

Advanced into this place," my Master said,

"Safe hitherto from all your skill of fence,

Without the will divine, and fate auspicious?

Let me go on, for it in Heaven is willed

That I another show this savage road."

Then was his arrogance so humbled in him,

That he let fall his grapnel at his feet,

And to the others said: "Now strike him not."

And unto me my Guide: "O thou, who sittest

Among the splinters of the bridge crouched down,

Securely now return to me again."

Wherefore I started and came swiftly to him;

And all the devils forward thrust themselves,

So that I feared they would not keep their compact.

And thus beheld I once afraid the soldiers

Who issued under safeguard from Caprona,

Seeing themselves among so many foes.[8]

Close did I press myself with all my person

Beside my Leader, and turned not mine eyes

From off their countenance, which was not good.

They lowered their rakes, and "Wilt thou have me hit him,"

They said to one another, "on the rump?"

And answered: "Yes; see that thou nick him with it."

But the same demon who was holding parley

With my Conductor turned him very quickly,

And said: "Be quiet, be quiet, Scarmiglione,"

Then said to us: "You can no farther go

Forward upon this crag, because is lying

All shattered, at the bottom, the sixth arch.

And if it still doth please you to go onward,

Pursue your way along upon this rock;

Near is another crag that yields a path.

Yesterday, five hours later than this hour,

One thousand and two hundred sixty-six

Years were complete, that here the way was broken.

I send in that direction some of mine

To see if any one doth air himself,

Go ye with them; for they will not be vicious.

Step forward, Alichino and Calcabrina,"

Began he to cry out, "and thou, Cagnazzo;

And Barbariccia, do thou guide the ten.[9]

Come forward, Libicocco and Draghignazzo,

And tusked Ciriatto and Graffiacane,

And Farfarello and mad Rubicante;

Search ye all round about the boiling pitch;

Let these be safe as far as the next crag,

That all unbroken passes o'er the dens."

"O me! what is it, Master, that I see?

Pray let us go," I said, "without an escort,

If thou knowest how, since for myself I ask none.

If thou art as observant as thy wont is,

Dost thou not see that they do gnash their teeth,

And with their brows are threatening woe to us?"

And he to me: "I will not have thee fear;

Let them gnash on, according to their fancy,

Because they do it for those boiling wretches."

Along the left-hand dike they wheeled about;

But first had each one thrust his tongue between

His teeth towards their leader for a signal;

And he had made a trumpet of his rump.

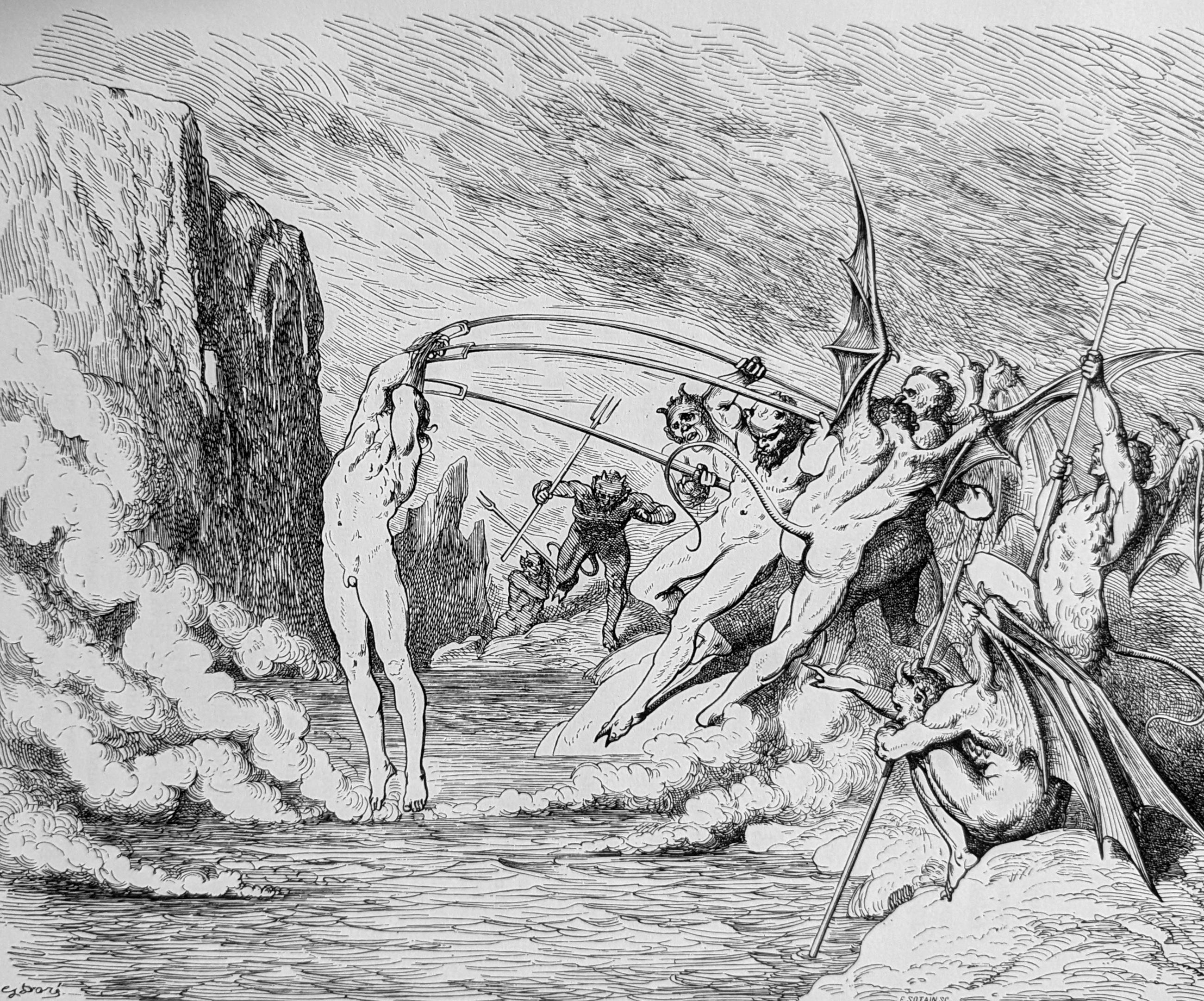

Illustrations

They seized him then with more than a hundred rakes; Inf. XXI, line 52

But he cried out: "Be none of you malignant!" Inf. XXI, line 72

Footnotes

1. Malebolge, "evil pockets".

2. Until the Industrial Revolution, the vast Arsenale in Venice, built in 1104, was the largest ship-building enterprise in the world. It was enclosed within a two-mile circuit of walls and towers that were closely guarded. Most of Venice’s military and merchant ships were constructed there and it obviously played a significant role in the wealth and sea power of the Venetian Republic. Because the operations were almost like the modern-day process of pre-fabrication, various parts of ships were constructed in different areas of the Arsenale and, amazingly, could be assembled into a completed ship in one day! We know that Dante was in Venice in 1321 as part of a diplomatic mission for his patron, Guido da Polenta, the Lord of Ravenna. Unfortunately, the Venetians would not allow him to return home by ship, so he was forced to return home through the swampy area along the coast. There Dante contracted malaria and died on September 14 of that same year. There is no hard evidence that he was in Venice before 1321, though it is possible that he was because he so thoroughly relates the workings of this amazing facility here.

3. As noted above, this devil is not far away from Dante and Virgil: he’s “on our bridge.” In Italian, malebranche means “evil claws,” and this devil is equipped with them as we’ve seen. He’s obviously addressing others like himself, but we don’t see them yet . Instead, we’re treated to a wild boast and a nasty poke at the city of Lucca. Saint Zita, a simple maidservant noted for her devotion and piety, was the patron Saint of Lucca, and the city was sometimes simply referred to as Santa Zita as the big devil do es here. She died in 1275, when Dante was only 10, so he would have had some knowledge of her later popularity.

4. As we get closer to the matter at hand in this canto, the devil shouts that he has over his shoulder one of the officials (elders) of Lucca’s city government. This sinner is unnamed, but we’re told that the city is filled with the likes of him – grafters, barrators, swindlers, and other abusers of public office who, like the simonists in Canto 19, violated the public trust through bribery and other acts of corruption. With one exception: an ironic joke pointed at the “innocent” Bonturo. Apparently, Bonturo Da ti was the most corrupt official in the city! Not far from Florence, Dante may have been to Lucca on more than one occasion before and after his exile and, either first-hand or through local gossip, came to know its unsavory reputation. More than this, however, Dante has a significant investment in this canto and the next one since the sin punished here is exactly the crime he was accused of before he was exiled from Florence. Some commentators note that in Dante’s Italian the devil’s remark about the buying and selling of nos and yeses is not the standard no and si. Rather, in another clever slap at the corrupt city elders the devil uses the Latin judicial form of yes, ita.

5. Now the major action of this canto gets underway. All the while, a group of devils were hiding underneath the bridge – unbeknownst to Dante and Virgil. Summoned into the open by the black devil and the splash of the sinner falling into the boiling pitch, they rush out, armed with their tridents, and begin to torture the poor creature by making sport of him. Once again, Dante’s devils are clever and now funny. Seeing the sinner stretched out like a cross, they begin their wicked taunts. The cathedral in Lucca is home to a very precious image of the crucified Jesus, known as the Volto Santo or “Holy Face.” It is said to have been started by one of Jesus’ disciples, Nicodemus, who fell asleep while carving it. When he awoke, it was miraculously finished. The wood of this image is dark, almost black, and seeing the sinner float up, stretched out like a cross, covered with black tar, the devils have a good time mocking him. But there’s more. The River Serchio, not far from Lucca, was (and still is) a very popular spot for the locals who flock there in the summer months to frolic in the sun and water. One can imagine bathers floating on their backs exactly like our sinner here. Except, as the devils quickly remind him, this is not the Serchio. Only now do we realize why Dante and Virgil saw no one when they looked down from the bridge over this bolgia: the sinners are all immersed deep within boiling pools of tar. Jabbing the newcomer with their tridents, the devils warn him to stay under and to do his cheating down in the sticky tar. And so this “slab of meat,” reminding Dante of a kitchen scene, is shoved under by the “kitchen boys” as it cooks for soup or stew. This image will continue into the next canto as well.

6. Latin, mendīcus, “beggarly, needy”, menda “physical defect, fault”.

7. The humor of this canto begins to seep out through the travelers’ precarious situation here. Virgil wants to speak with someone in charge, someone who will respect his heavenly commission. Instead, he soon finds himself face to face with the captain of this farcical platoon of devils: Malacoda. In Italian, this means “evil tail,” a fitting name to remember when we arrive at the end of this canto. For now, Virgil may be self-confident, but he’s out of his element. Malacoda’s confidence, on the other hand, is over-inflated, and he’s dying for some little mis-step on Virgil’s part that will give him and his troop an excuse to use their tridents. He expects that Virgil will back down, but hearing Virgil recite his passport, this over-inflated devil collapses like Plutus did at the beginning of Canto 6.

8. Called out from his hiding place, Dante approaches Virgil with rightful trepidation as he recalls a scene from his military experience. Caprona was a fortified castle along the Arno River not far from Pisa. In 1289 it was finally captured by an army made up of soldiers from Florence and Lucca, among them Dante Alighieri. His recollection of this scene is accurate as far as he tells it here. When the siege was over and a truce established, the frightened troops inside the fortress were marched out between line s of invading soldiers. According to some accounts of this battle, the truce was almost immediately violated and the unarmed soldiers were brutally slain. Other accounts had them being led away and let go. One way or the other, Dante had reason to fear for his life in spite of Virgil’s assurances to the contrary. Virgil is dead, a spirit; but Dante, we must remember, is still very much alive – and, as we see him now, rather childishly clinging onto his mentor.

9. After hearing the names of this infernal platoon and watching their antics (and there is more devilment in store), is it any wonder that Cantos 21 and 22 have been called the “Gargoyle Cantos”? A great deal of commentary has been written on the names of these ten demons in an attempt to decipher their meaning, or to connect their behavior with their names, or even to discover whether Dante might have taken prominent (read dislikable) figures in his own day and played with their names. In the end, the names simply work best by themselves because they’re as nonsensical and preposterous as the place where we find them! Over the years, several English translators of this canto give this platoon a different – and ridiculous – set of names. One can imagine Dante having fun creating this comical scene of “the calling.” In keeping with the theme of infernal disrespect, Malacoda calls his apostles and sends them forth on a mission, just as Christ did with his own apostles (in Greek, “one who is sent”). Dante is threading comical beads together here: we are in malebolge (“evil pockets”) where the malebranche (“evil claws”) led by malacoda (“evil tail”) torment the “evil….” And at the end of this scene Malacoda reminds his companions to keep their new charges safe – all the way to the non-existent bridge!

Top of page