Dante's Divine Comedy: Inferno

Canto XXXI

Dante and Virgil leave the domain of Simple Fraud and journey from the Malebolge into Cocytus, the central lake of ice, where Complex Fraud is punished. The surrounding silence is broken by the piercing blast of Nimrod's distant horn. He and other giants are forever fixed to the pit of Hell for having violently rebelled against Jove {Jupiter}. Only Antaeus may speak and is unchained. At Virgil's request, he picks the pair of poets up in his enormous hand and deposits them below.

One and the selfsame tongue first wounded me,

So that it tinged the one cheek and the other,

And then held out to me the medicine;

Thus do I hear that once Achilles' spear,

His and his father's, used to be the cause

First of a sad and then a gracious boon.

We turned our backs upon the wretched valley,

Upon the bank that girds it round about,

Going across it without any speech.

There it was less than night, and less than day,

So that my sight went little in advance;

But I could hear the blare of a loud horn,

So loud it would have made each thunder faint,

Which, counter to it following its way,

Mine eyes directed wholly to one place.

After the dolorous discomfiture

When Charlemagne the holy emprise lost,

So terribly Orlando sounded not.[1]

Short while my head turned thitherward I held

When many lofty towers I seemed to see,

Whereat I: "Master, say, what town is this?"

And he to me: "Because thou peerest forth

Athwart the darkness at too great a distance,

It happens that thou errest in thy fancy.

Well shalt thou see, if thou arrivest there,

How much the sense deceives itself by distance;

Therefore a little faster spur thee on."

Then tenderly he took me by the hand,

And said: "Before we farther have advanced,

That the reality may seem to thee

Less strange, know that these are not towers, but giants,

And they are in the well, around the bank,

From navel downward, one and all of them."

As, when the fog is vanishing away,

Little by little doth the sight refigure

Whate'er the mist that crowds the air conceals,

So, piercing through the dense and darksome air,

More and more near approaching tow'rd the verge,

My error fled, and fear came over me;

Because as on its circular parapets

Montereggione crowns itself with towers,

E'en thus the margin which surrounds the well[2]

With one half of their bodies turreted

The horrible giants, whom Jove menaces

E'en now from out the heavens when he thunders.

And I of one already saw the face,

Shoulders, and breast, and great part of the belly,

And down along his sides both of the arms.

Certainly Nature, when she left the making

Of animals like these, did well indeed,

By taking such executors from Mars;

And if of elephants and whales she doth not

Repent her, whosoever looketh subtly

More just and more discreet will hold her for it;

For where the argument of intellect

Is added unto evil will and power,

No rampart can the people make against it.

His face appeared to me as long and large

As is at Rome the pine-cone of Saint Peter's,

And in proportion were the other bones;

So that the margin, which an apron was

Down from the middle, showed so much of him

Above it, that to reach up to his hair

Three Frieslanders in vain had vaunted them;

For I beheld thirty great palms of him

Down from the place where man his mantle buckles.[3]

"Raphael mai amechitabi almi,"

Began to clamor the ferocious mouth,

To which were not befitting sweeter psalms.[4]

And unto him my Guide: "Soul idiotic.

Keep to thy born, and vent thyself with that.

When wrath or other passion touches thee.

Search round thy neck, and thou wilt find the belt

Which keeps it fastened, O bewildered soul,

And see it, where it bars thy mighty breast."

Then said to me: "He doth himself accuse

This one is Nimrod, by whose evil thought

One language in the world is not still used.[5]

Here let us leave him and not speak in vain.

For even such to him is every language

As his to others, which to none is known."

Therefore a longer journey did we make,

Turned to the left, and a crossbow-shot oft

We found another far more fierce and large.

In binding him, who might the master be

I cannot say; but he had pinioned close

Behind the right arm, and in front the other,

With chains, that held him so begirt about

From the neck down, that on the part uncovered

It wound itself as far as the fifth gyre.[6]

"This proud one wished to make experiment

Of his own power against the Supreme Jove,"

My Leader said, "whence he has such a guerdon.[7]

Ephialtes is his name; he showed great prowess.

What time the giants terrified the gods;

The arms he wielded never more he moves."[8]

And I to him: "If possible, I should wish

That of the measureless Briareus

These eyes of mine might have experience."[9]

Whence he replied: "Thou shalt behold Antaeus

Close by here, who can speak and is unbound,

Who at the bottom of all crime shall place us.[10]

Much farther yon is he whom thou wouldst see,

And he is bound, and fashioned like to this one,

Save that he seems in aspect more ferocious."

There never was an earthquake of such might

That it could shake a tower so violently,

As Ephialtes suddenly shook himself.

Then was I more afraid of death than ever,

For nothing more was needful than the fear,

If I had not beheld the manacles.

Then we proceeded farther in advance,

And to Antaeus came, who, full five ells

Without the head, forth issued from the cavern.[11]

"O thou, who in the valley fortunate,

Which Scipio the heir of glory made,

When Hannibal turned back with all his hosts,[12]

Once brought'st a thousand lions for thy prey,

And who, hadst thou been at the mighty war

Among thy brothers, some it seems still think

The sons of Earth the victory would have gained:

Place us below, nor be disdainful of it,

There where the cold doth lock Cocytus up.

Make us not go to Tityus nor Typhoeus;

This one can give of that which here is longed for;

Therefore stoop down, and do not curl thy lip.[13]

Still in the world can he restore thy fame;

Because he lives, and still expects long life,

If to itself Grace call him not untimely."

So said the Master; and in haste the other

His hands extended and took up my Guide,--

Hands whose great pressure Hercules once felt.[14]

Virgilius, when he felt himself embraced,

Said unto me: "Draw nigh, that I may take thee;"

Then of himself and me one bundle made.

As seems the Carisenda, to behold

Beneath the leaning side, when goes a cloud

Above it so that opposite it hangs;[15]

Such did Antaeus seem to me, who stood

Watching to see him stoop, and then it was

I could have wished to go some other way.

But lightly in the abyss, which swallows up

Judas with Lucifer, he put us down;

Nor thus bowed downward made he there delay,

But, as a mast does in a ship, uprose.

Illustrations

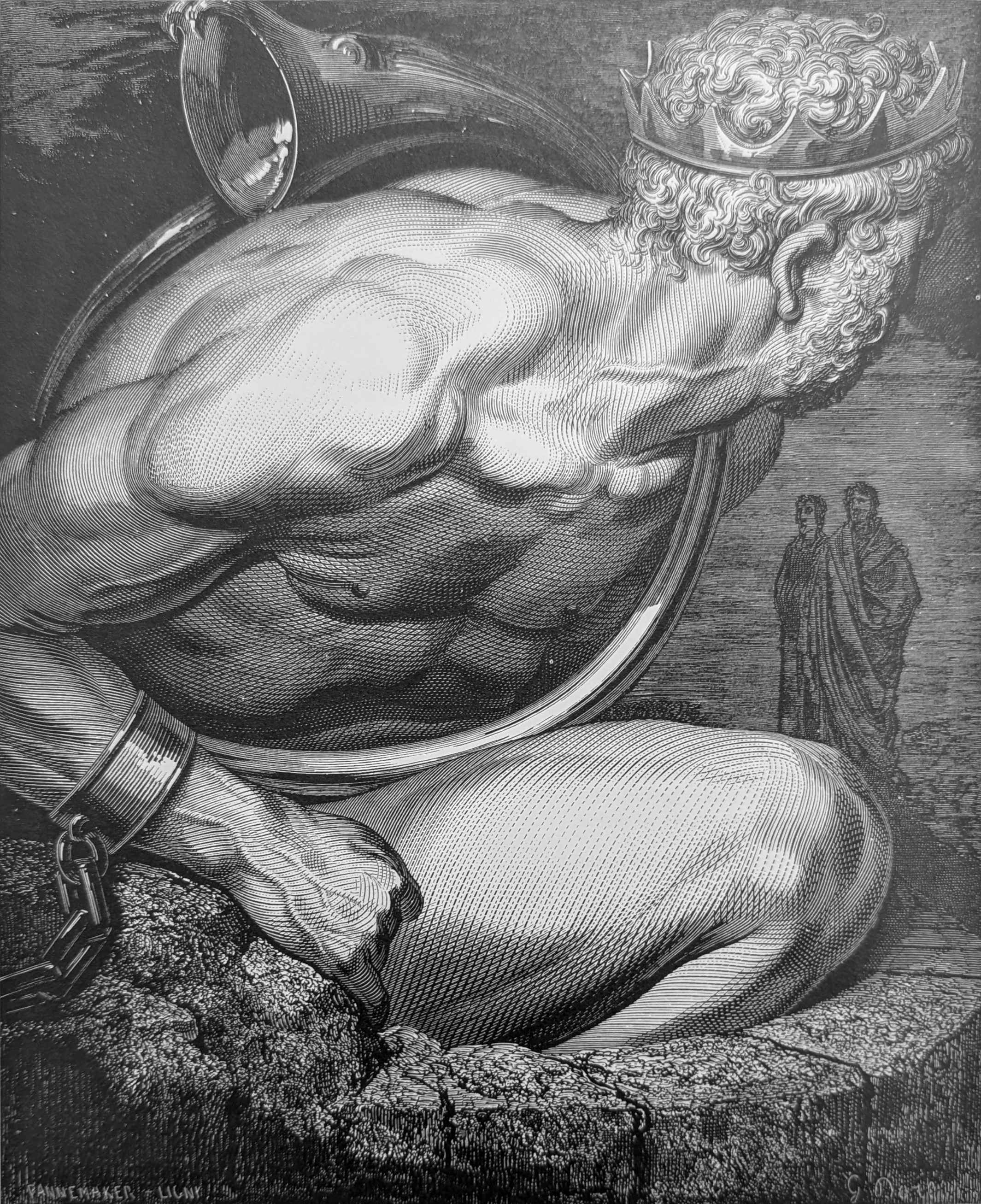

"Soul idiotic, / Keep to thy horn, and vent thyself with that, / When wrath or other passion touches thee." Inf. XXXI, lines 70-72

"This proud one wished to make experiment / Of his own power against the Supreme Jove," Inf. XXXI, lines 91-92

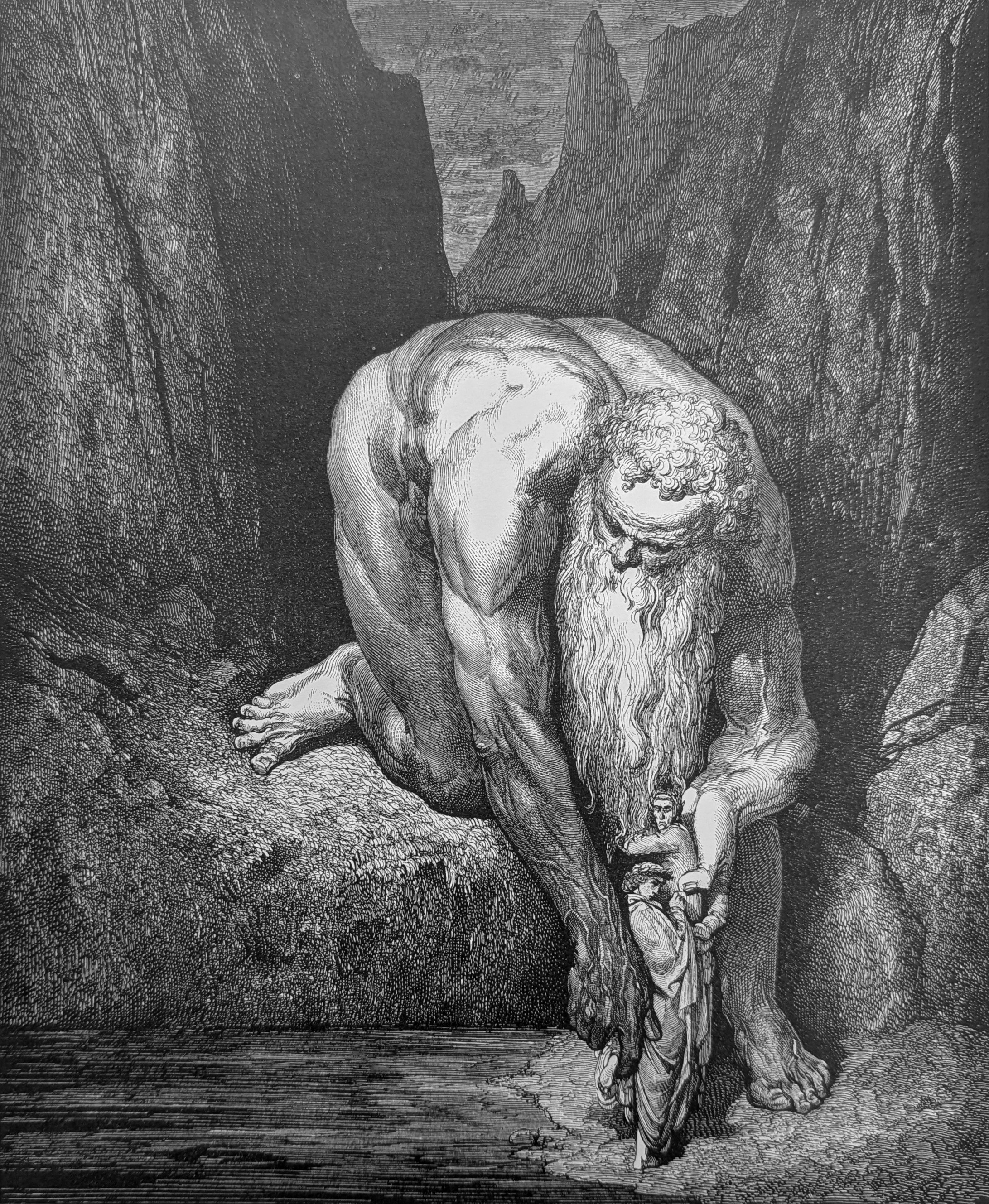

But lightly in the abyss, which swallows up / Judas with Lucifer, he put us down; Inf. XXXI, lines 142-143

Footnotes

1. Quietly making their way along what turns out to be a large plain leading away from the final wall of Malebolge, the silence is broken suddenly by the sound of an immense horn. While the thunderous blast makes Dante look for where it came from, it also reminds him of the scene when the forces of Charlemagne were routed. His nephew, Roland (see the Song of Roland), was bringing up the rear-guard of Charlemagne’s army through the Pyrenees when they were attacked at Roncesvalles and killed by the Saracens. When the attack started, Roland should have blown his signal horn, but he was too proud to do so, and was also killed in the battle. However, with his dying breath he blew the horn so loudly that Charlemagne heard it 8 miles away! The king, deceived into thinking that Roland was simply hunting, ignored the signal. The note of treachery “sounded” here will be taken up in full once Dante and Virgil reach the bottom of Hell in the next canto.

2. Dante’s fear takes over for a moment and he addresses the reader with what might be a tourist’s remembrance, but apropos of the present situation. If Italian city-scapes bristled with towers, the Italian countryside was strategically dotted with hilltops cap ped by walled-in cities with great towers built into the walls. Dante mentions one of the more famous of these hilltop castle-towns, Monteriggioni, about 18 miles north of Siena, which is very well-preserved to this day. Seeing the city from the distance on e can well-imagine its 14 wall-towers as Dante’s “giants.” Of course, the giants here are all known mythological figures and, once again, Dante has them guarding the entrance to the ninth and final circle of Hell. They represent pride on a colossal level, having once threatened Jupiter. Now they stand here shuddering at Jupiter’s retribution. We will learn more about them momentarily.

3. Comparing just the giant’s face with the pinecone the face is already an amazing 12 feet high. But Dante adds the three Frisians here and amplifies the truth of his comparison. Frisians, also known as Frieslanders, inhabit the northern coastal regions of the Netherlands. They are noted for their height, and Dante probably encountered some of them during his travels in the north. Three of them standing at the edge of the well, on each other’s shoulders, might have reached about 19 feet.

4. No one in the history of Dante study has deciphered Nimrod’s gibberish, though many have tried or offered suggestions. Hollander calls it “a veritable orgy of interpretive enthusiasm.” On one level, it’s simply a come-on to amplify the dim scene that Dante had already misinterpreted. And it’s appropriate that the classical master of elegant language—Virgil—should be the one to reply to him, even though Virgil’s response is hardly elegant.

5. Understanding the figure of Nimrod, whether real or fictional, is a complex historical enterprise. Even before he wrote the Inferno, Dante highlighted Nimrod in Part VII of his De Vulgari Eloquentia:

“Incorrigible humanity, therefore, led astray by the giant Nimrod, presumed in its heart to outdo in skill not only nature but the source of its own nature, who is God; and began to build a tower in Sennaar, which afterwards was called Babel (that is, ‘confusion’). By this means human beings hoped to climb up to heaven, intending in their foolishness not to equal but to excel their creator.”

6. Latin, gȳrus, “circle; circular motion”, Greek, γῦρος, gûros, “circle; ring”, meaning a vortex.

7. Middle English, guerdon, guerdoun, gardone, French, guerdon, guerredon, guarredon, werdon, Latin, widerdōnum, Germanic, widarlōn, Latin, dōnum, “gift”.

8. Dante reminds us now of the travelers’ movements—along the edge of the well to the left, as with most of their turns, and notes that it’s much farther to the next giant than it was from the last wall of Malebolge to Nimrod. Here we meet the fearsome giant Ephialtes, so fearsome that Dante, amazed, is careful to note the exact manner by which he is bound and chained, and he expresses admiration for the one who did this. Virgil explains—in very neutral terms compared to his dealings with Nimrod—that Hell is the “prize” for his pride and violence against God/s. Sons of Neptune, Ephialtes and his twin brother, Otus, are mentioned by Homer, Statius, and Virgil. It’s hard to imagine, but at nine years old and reputed to be at least 60 feet tall, they attempted to pile two mountains on top of Mount Olympus, storm heaven, and make war on the gods. Apollo and Diana slew both of them and the heavenly order of things was restored.

9. Apart from sheer curiosity, it’s hard to know why Dante was so intent on seeing the giant Briareus. Whatever his reasons were, Virgil dissuades him from pursuing the matter by telling him that Briareus was more fierce than Ephialtes and that Antaeus will help them. Then, as though on cue, Ephialtes’ violent struggling against his chains almost literally scares Dante to death.

10. Antaeus, a benign giant, is the last one we will meet. He was the son of Neptune and Earth and is the only one of the giants (apart from Nimrod) who did not threaten violence against the gods at the great battle of Phlegra (located on the present-day peninsula of Kassandra in Chalkidiki, Greece). He lived in the area of Libya and was renowned for his strength. Because his mother was Gaia (Earth), contact with the earth continually renewed his strength. Discovering this, Hercules defeated and killed him in a wrestling match by holding him up and off the ground. As Dante has done with other characters in Hell, so Virgil here not only flatters Antaeus, but urges him to help them for the sake of his fame which Dante—“this living man here”—can keep alive on earth . And, being the most benign of the six giants standing in the great well, he’s obviously the most likely to help the travelers overcome the last barrier on their journey to the bottom of Hell as Geryon did at the end of Canto 17.

11. Apart from sheer curiosity, it’s hard to know why Dante was so intent on seeing the giant Briareus. Whatever his reasons were, Virgil dissuades him from pursuing the matter by telling him that Briareus was more fierce than Ephialtes and that Antaeus will he lp them. Then, as though on cue, Ephialtes’ violent struggling against his chains almost literally scares Dante to death.

Briareus, the son of Uranus and Earth, was a monstrosity of a giant. In his Aeneid (X:565ff) Virgil describes him as having had

“a hundred arms and a hundred hands they say, and breathed fire from fifty chests and mouths, when he clashed with as many like shields of his and drew as many swords against Jove’s lightning-bolts.”

No wonder Dante was so curious to see him. Joining the Titans in their revolt against the gods, Briareus was killed by Jove and buried under Mt. Etna in Sicily.

Ells, pleural of ell, Middle English, elle, elne, Old English eln, “the length of the forearm from the elbow to the tip of the middle finger”.

12. Antaeus, a benign giant, is the last one we will meet. He was the son of Neptune and Earth and is the only one of the giants (apart from Nimrod) who did not threaten violence against the gods at the great battle of Phlegra (located on the present-day penin sula of Kassandra in Chalkidiki, Greece). He lived in the area of Libya and was renowned for his strength. Because his mother was Gaia (Earth), contact with the earth continually renewed his strength. Discovering this, Hercules defeated and killed him in a wrestling match by holding him up and off the ground. As Dante has done with other characters in Hell, so Virgil here not only flatters Antaeus, but urges him to help them for the sake of his fame which Dante-–“this living man here”-–can keep alive on earth . And, being the most benign of the six giants standing in the great well, he’s obviously the most likely to help the travelers overcome the last barrier on their journey to the bottom of Hell as Geryon did at the end of Canto 17. In line with Virgil’s flat tery of Antaeus, it’s worth including Hollander’s insight that, in his request for the giant’s assistance, Virgil actually quotes historical items that are drawn from Lucan. We’re very accustomed to Dante drawing from many different sources. Not Virgil.

Then, in quick succession, Virgil’s request includes other names and points of interest that lend continual reality to this canto. Cocytus is the name given to the last of the four rivers of Dante’s Hell. It is frozen and constitutes the very bottom of Hell –-its ninth and last circle. The Battle at Zama (about 100 miles southwest of Tunis) marks the place where the Second Punic War ended in 202 BC with Scipio defeating Hannibal. It is said that Antaeus lived in a great cave not far from the battle site. Tityu s and Typhon are the last of the six giants that stand in the great well leading to the bottom of Hell. Dante seems to ignore them except in this mention by Virgil. Tityus was born of Zeus and the mortal princess Elara. Well before his birth he was so large that he burst out of his mother’s womb. Killed for attempting to rape Leto, the mother of Apollo and Artemis, he was punished by being bound in the underworld and every night two vultures ate out his liver which, by morning, would regenerate.

13. Typhon was a monstrous giant, one of the most feared and dangerous, and said to be so large he could reach the sky. He was the son of Gaia and Tartarus. Like other giants here, he made war against the gods-–in his case, attempting to overthrow Zeus, who ki lled him with his thunderbolts. He is often described as a mixture of features: serpentine, winged, and human. In his Theogony, the Greek poet Hesiod offers this amazing description:

“Strength was with his hands in all that he did and the feet of the strong god were untiring. From his shoulders grew a hundred heads of a snake, a fearful dragon, with dark, flickering tongues, and from under the brows of his eyes in his marvelous heads flashed fire, and fire burned from his heads as he glared. And there were voices in all his dreadful heads which uttered every kind of sound unspeakable; for at one time they made sounds such that the gods understood, but at another, the noise of a bull be llowing aloud in proud ungovernable fury; and at another, the sound of a lion, relentless of heart; and at another, sounds like whelps, wonderful to hear; and again, at another, he would hiss, so that the high mountains re-echoed.”

It’s curious that Dante asked Virgil to see the ferocious Briaraeus but seems to pass by Typhon who is worse. On the other hand, it was most likely the case that after he and Virgil encountered Nimrod, they continued moving around the edge of the great well to their left. Soon they encountered Ephialtes. At that point, Dante asked about seeing Briareus, but Virgil warned him against it. Finally, they come to Antaeus, the last giant they encounter. Tityus and Typhon are only mentioned at this point, and it’s p robable that they along with Briareus are standing further along the circle of the well beyond Antaeus. It might be that one of these three was to the right of Dante and Virgil when they first encountered Nimrod, but they turned and followed a leftward path along the rim of the well.

List of Six Giants:

• Antaeus

• Briaraeus

• Ephialtes

• Nimrod

• Tityus

• Typhon

14. But, as noted earlier, Hercules may have felt the strength of Antaeus’ hands, but in that wrestling match, it was Hercules who killed him.

15. Dante's mention of the Garisenda Tower (next to Asinelli Tower), very near the university in Bologna, is both clever and delightfully “touristy.” And it’s the last of several points in this canto added to increase the sense of reality. It’s also the second time in this canto that he alludes to a significant Italian landmark–-the first one being Monterigioni. There are actually two notable towers in Bologna, they are quite close to each other, and both of them lean. The Garisenda Tower was erected by the Gar isendi brothers in 1110. It stands 163 feet tall and leans 10 feet off perpendicular! Originally, it stood much taller, but it was shortened in 1355. The Asinelli Tower next to it stands 320 feet and leans four feet off the perpendicular. As noted earlier i n this canto, major Italian cities seemed to bristle with towers, and Medieval Bologna had close to 100 according to modern estimates. We know that Dante was there, probably several times in different capacities, and he surely did what every tourist does: h e stood under the leaning side of the Garisenda when a cloud passed overhead and enjoyed the thrill of the illusion that the tower was falling over on him. And so, as this canto opened with Dante thinking he saw towers in the dim distance, he closes it with the pleasant recollection of a real one. But now-–having encountered giants and towers–-we are left standing on the floor of Hell.

Top of page