Dante's Divine Comedy: Inferno

Canto XXXII

As they descend into Cocytus, Virgil and Dante see more and more Traitors frozen in the vast icy plain. Those who murdered their kindred lie in Caina, its outer margin. The Alberti brothers, among others, are trapped in a deadly embrace. The travelers next enter Antenora, the second division. Dante kicks the protruding head of Bocca Degli Abati and furiously pulls his hair so he will utter his name. A traitor to his country, the Ghibelline appeared to support the Guelf cause. He angrily names and shames five companions. Dante glimpses two more heads, one feasting on the brains of the other.

If I had rhymes both rough and stridulous,

As were appropriate to the dismal hole

Down upon which thrust all the other rocks,

I would press out the juice of my conception

More fully; but because I have them not,

Not without fear I bring myself to speak;

For 'tis no enterprise to take in jest,

To sketch the bottom of all the universe,

Nor for a tongue that cries Mamma and Babbo.

But may those Ladies help this verse of mine,

Who helped Amphion in enclosing Thebes,

That from the fact the word be not diverse.[1]

O rabble ill-begotten above all,

Who're in the place to speak of which is hard,

"Twere better ye had here been sheep or goats![2]

When we were down within the darksome well,

Beneath the giant's feet, but lower far,

And I was scanning still the lofty wall,

I heard it said to me: "Look how thou steppest!

Take heed thou do not trample with thy feet

The heads of the tired, miserable brothers!"

Whereat I turned me round, and saw before me

And underfoot a lake, that from the frost

The semblance had of glass, and not of water.

So thick a veil ne'er made upon its current

In winter-time Danube in Austria,

Nor there beneath the frigid sky the Don,[3]

As there was here; so that if Tambernich

Had fallen upon it, or Pietrapana,

E'en at the edge 'twould not have given a creak.

And as to croak the frog doth place himself

With muzzle out of water, —when is dreaming

Of gleaning oftentimes the peasant-girl,—

Livid, as far down as where shame appears,

Were the disconsolate shades within the ice,

Setting their teeth unto the note of storks.

Each one his countenance held downward bent;

From mouth the cold, from eyes the doleful heart

Among them witness of itself procures.

When round about me somewhat I had looked,

I downward turned me, and saw two so close,

The hair upon their heads together mingled.

"Ye who so strain your breasts together, tell me,"

I said, "who are you;" and they bent their necks,

And when to me their faces they had lifted,

Their eyes, which first were only moist within,

Gushed o'er the eyelids, and the frost congealed

The tears between, and locked them up again.

Clamp never bound together wood with wood

So strongly; whereat they, like two he-goats,

Butted together, so much wrath o'ercame them.

And one, who had by reason of the cold

Lost both his ears, still with his visage downward,

Said: "Why dost thou so mirror thyself in us?

If thou desire to know who these two are,

The valley whence Bisenzio descends

Belonged to them and to their father Albert.[4]

They from one body came, and all Caina

Thou shalt search through, and shalt not find a shade

More worthy to be fixed in gelatine;[5]

Not he in whom were broken breast and shadow

At one and the same blow by Arthur's hand;

Focaccia not; not he who me encumbers[6]

So with his head I see no farther forward,

And bore the name of Sassol Mascheroni;

Well knowest thou who he was, if thou art Tuscan.

And that thou put me not to further speech,

Know that I Camicion de' Pazzi was,

And wait Carlino to exonerate me."[7]

Then I beheld a thousand faces, made

Purple with cold; whence o'er me comes a shudder,

And evermore will come, at frozen ponds.

And while we were advancing tow'rds the middle,

Where everything of weight unites together,

And I was shivering in the eternal shade,

Whether 'twere will, or destiny, or chance,

I know not; but in walking 'mong the heads

I struck my foot hard in the face of one.

Weeping he growled: "Why dost thou trample me?

Unless thou comest to increase the vengeance

of Montaperti, why dost thou molest me?"[8]

And I: "My Master, now wait here for me,

That I through him may issue from a doubt;

Then thou mayst hurry me, as thou shalt wish."

The Leader stopped; and to that one I said

Who was blaspheming vehemently still:

"Who art thou, that thus reprehendest others?"

"Now who art thou, that goest through Antenora

Smiting," replied he, "other people's cheeks,

So that, if thou wert living, 'twere too much?"

"Living I am, and dear to thee it may be,"

Was my response, "if thou demandest fame,

That 'mid the other notes thy name I place."

And he to me: "For the reverse I long;

Take thyself hence, and give me no more trouble;

For ill thou knowest to flatter in this hollow."

Then by the scalp behind I seized upon him,

And said: "It must needs be thou name thyself,

Or not a hair remain upon thee here."

Whence he to me: "Though thou strip off my hair,

I will not tell thee who I am, nor show thee,

If on my head a thousand times thou fall."

I had his hair in hand already twisted,

And more than one shock of it had pulled out,

He barking, with his eyes held firmly down,

When cried another: "What doth ail thee, Bocca?

Is't not enough to clatter with thy jaws,

But thou must bark? what devil touches thee?"[9]

"Now," said I, "I care not to have thee speak,

Accursed traitor; for unto thy shame

I will report of thee veracious news."

"Begone," replied he, "and tell what thou wilt,

But be not silent, if thou issue hence,

Of him who had just now his tongue so prompt;

He weepeth here the silver of the French;

'I saw,' thus canst thou phrase it, 'him of Duera

There where the sinners stand out in the cold.'[10]

If thou shouldst questioned be who else was there,

Thou hast beside thee him of Beccaria,

Of whom the gorget Florence slit asunder,

Gianni del Soldanier, I think, may be

Yonder with Ganellon, and Tebaldello

Who oped Faenza when the people slept."

Already we had gone away from him,

When I beheld two frozen in one hole,

So that one head a hood was to the other;

And even as bread through hunger is devoured,

The uppermost on the other set his teeth,

There where the brain is to the nape united.

Not in another fashion Tydeus gnawed

The temples of Menalippus in disdain,

Than that one did the skull and the other things.[11]

"O thou, who showest by such bestial sign

Thy hatred against him whom thou art eating,

Tell me the wherefore," said I, "with this compact,

That if thou rightfully of him complain,

In knowing who ye are, and his transgression,

I in the world above repay thee for it,

If that wherewith I speak be not dried up."

Illustrations

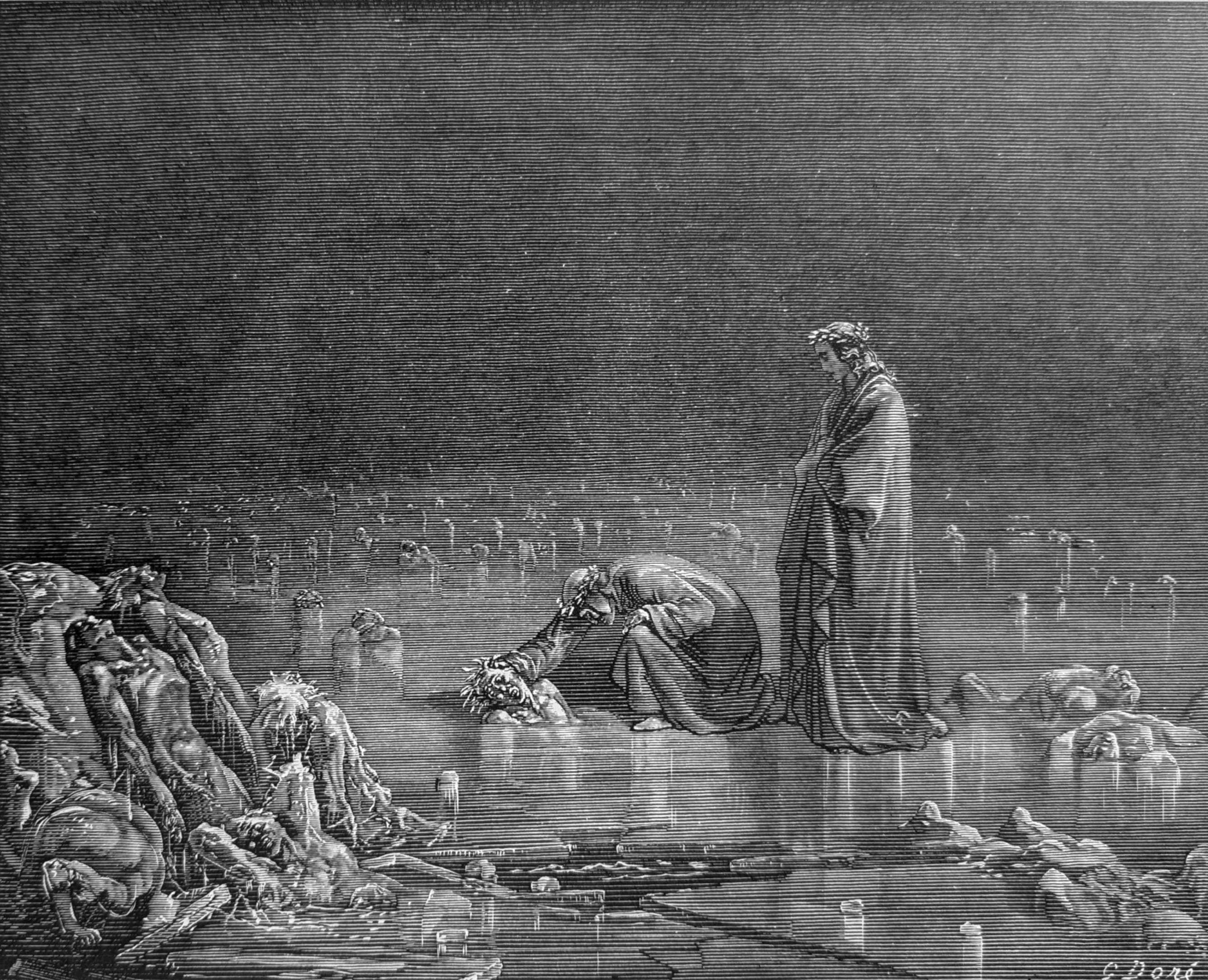

"Look how thou steppest! / Take heed thou do not trample with thy feet/ The heads of the tired, miserable brothers!" Inf. XXXII, lines 19-21

Then by the scalp behind I seized upon him, / And said: "It must needs be thou name thyself, / Or not a hair remain upon thee here," Inf. XXXII, lines 97-99

The uppermost on the other set his teeth, / There where the brain is to the nape united. Inf. XXXII, lines 128-129

Footnotes

1. Dante’s reference to the bottom of the universe is, in fact, where we are now. Although we haven’t seen it yet in its full form, recall that he uses the geocentric Ptolemaic model of the cosmos as the superstructure for the Commedia, and if the Earth is at the center of that cosmos, then he is now at the “center of the center.” From this point, no matter which way you go, literally everything in the universe is up. Thinking of structures, then, Dante calls on the Muses to help him in this seemingly impossible task as they once helped Amphion, King of Thebes, in his building the walls of Thebes. Amphion and Zethus were twin sons of Zeus, and Amphion was famed as a musician—so much so that when he and his brother were building the walls of Thebes, Zethus carried the stones, but Amphion played such beautiful music on the lyre given to him by Hermes that he charmed the stones in nearby Mount Cithaeron to move on their own and place themselves into the walls. That Dante refers to this story, which he borrows from Statius and Horace, is obviously significant at this point in the poem. First, in a sense he’s been Amphion’s twin, Zethus, carrying the “stones” of his Inferno up to this point. Realizing that he can no longer support the weight of his story by himself, he becomes Amphion by virtue of his invocation of the Muses, hoping to rely on their inspiration to bring the heaviest stones into the edifice of these last cantos. Second, it’s appropriate that he refer to Thebes here because in the ancient world the city had a reputation for treachery, and the entire bottom of Hell here will be filled with traitors. And, perhaps, what Dante has in mind here with reference to Amphion is to wall up all the traitors he will meet here. He will mention this evil city again in this canto and in the next one.

2. When the Poet brings his introduction and his invocation to a close he includes those he now realizes he has to write about: “impossible to count – let alone describe.” Quoting the Gospel of Matthew (26:24) he apostrophizes, using the words of Jesus about his betrayer, Judas, wishing that they had never been born, because, as he writes in the Italian, they were mal creata, “badly created!” To suggest that these most terrible sinners should have been sheep and goats is to highlight again what Virgil told him near the beginning of Canto 3 when they passed through the gate into Hell: “…these are souls who lost the good of their intellect.” In other words, by their free choice they lost their minds and gave up their wills. And so they have become like animals. Ironically, animals can’t sin.

3. The Danube and the Don are two great European rivers. The Danube, second longest river in Europe (the first is the Volga), rises in western Germany, flows southeastward some 1,800 miles, and empties into the Black Sea. The Don is the fifth longest river in Europe. It rises at Novomoskovsk in western Russia and flows southwestward for 1,200 miles where it empties into the Sea of Azov (a northeastern section of the Black Sea). Mount Tambernic has never been located precisely by Dante scholars, and Mount Pietrapana is a rocky peak located in northwest Tuscany, today called Pania della Croce or la Pania. All along Dante wants to impress upon the reader the almost diamond-like clarity and solidity of this lake which is formed by Hell’s fourth “river,” Cocytus, which means “lamentation.” Like the other rivers of Dante’s Hell, Cocytus was formed from the tears of the Old Man of Crete statue in Canto 14. There, in the Italian, Dante refers to Cocytus as a pool or pond. Then, to confirm the strength of this ice lake, Dante notes that the two mountain peaks he mentioned—if they were to fall on this lake—wouldn’t make even a crack.

4. The chatty treacherous sinner who speaks here will soon be identified. But not before he betrays the identity of the two “glued” sinners above. And he’s clever enough not to change the position of his down-looking head (staring at himself in the “icy mirror”) so that his tears don’t freeze on his face like the two he “tells on.” Like other almost unnoticeable items in this canto, the icy mirror of the lake is most likely part of the contrapasso for these particular traitors. With heads bent down in shame, they have to look at themselves for all eternity.

So, without having been asked, this sinner eagerly takes over and tells Dante much more than he might have expected to hear. And worse, as befitting a traitor, he paints the two as the worst of their kind in his exaggerated tattle. The two tightly-bound sinners were Alessandro and Napoleone degli Alberti, sons of Alberto Degli Alberti, Counts of Mangona. This small town about 20 miles north of Florence is the location of the castle of the Alberti counts. It lies in the valley of the Bisenzio River which flows into the Arno about 10 miles west of Florence. The two brothers, reputed to be constantly at odds, came to a mortal dispute over which one inherited their father’s castle and ended up killing each other. Singleton here notes from the chronicler, Villani, that the castle of Mangona belonged by right to Alessandro, a Guelph and the younger of the two brothers, and was unjustly seized by Napoleone, who was a Ghibelline. Note, once again, how the constant feuding between Guelphs and Ghibellines is like an ugly thread running through the tapestry of Dante’s Poem.

5. In his exaggerated betrayal of the Alberti brothers, this sinner, who still has not identified himself, tells Dante the name of this part of Hell: Caïna, a word which refers to Cain, the killer of his brother, Abel, in chapter 4 of the Book of Genesis. Thus, Dante’s placement of these two brothers here is appropriate. The reference to “this icy broth” is morbid humor on the part of the sinner who is speaking. In the Italian, Dante calls it gelatina—just what it sounds like.

Before proceeding further, one thing should be clear by now: the entire bottom of Dante’s Hell is reserved for those who committed treachery of various kinds. This ninth circle of Hell is subtly divided into four concentric rings where successively worse kinds of treachery are punished. As noted above, (a) Caïna is the name of the first, outer circle, and contains those who committed acts of treachery against their family. (b) The second circle is named Antenora after Antenor, a Trojan soldier who betrayed his city to the Greeks. In this circle are punished those who betrayed their party or their country. (c) The third circle is named Ptolomea after Ptolemy, the governor of Jericho, who invited Simon Maccabaeus and his sons to a banquet during which he killed them (1 Macc. 16:11ff). In this circle are traitors to hospitality and friendship. (d) And finally, the fourth circle is called Judecca after Judas Iscariot who betrayed Jesus. This last and innermost circle of Cocytus is reserved for those who betrayed their masters and benefactors. Unlike the higher regions of Dante’s Hell, these four divisions of Cocytus are not clearly marked apart from each other but flow rather subtly one into the other.

6. Mordred was the treacherous nephew of King Arthur who, when Arthur went abroad to battle, usurped the throne and took the queen as his wife. Arthur returned to Britain and killed him as described here.

Focaccia was a member of the Cancellieri family of Pistoia (about 20 miles northwest of Florence). His treacherous murder of his cousin Detto is said to have started the split of the Pistoian Guelfs into Whites and Blacks. Florence became involved in the uprising there and, unfortunately, brought the White/Black split home to its own Guelfs.

Sassolo Mascherone, who must be close enough to the speaker (like Alessandro and Napoleone whom he’s blabbing on about) to block his view (of Dante? Of the rest of Caïna?), was a member of the Toschi family of Florence. He murdered a family member (it is not clear whether it was a cousin or a nephew) in order to get his property and money. Both his crime and the manner of his execution were well-known throughout Tuscany: he was sealed in a barrel filled with spikes and rolled down the streets! Following this he was beheaded.

7. Finally, our treacherous narrator identifies himself—as though to save Dante the trouble of asking! He does this in such a candid and brief manner that one might think that “murderer” were part of his name. As a matter of fact, he’s here for the murder of a kinsman named Ubertino with whom, jointly, he apparently owned a certain castle. Alberto “Camicion” de’Pazzi was from the area of Valdarno, one of the valleys of the Arno river about 25 miles south of Florence. When he first interrupted Dante he was described as missing his ears—subtly symbolic, as Plumptre suggests, of “those who yield to hatred and lose their power of listening to the voice of reason or conscience.” Of course, he has been so busy verbally betraying his neighbors it would seem that he has no time to listen!

Not done with his treacherous identifications, Camicion uses the power of damned souls to see into the future. (Recall Farinata in Canto 10 telling Dante about this.) He tells Dante that he’s waiting for his cousin who’s worse than he is, obviously a way of making himself look less culpable. This cousin, Carlino de’Pazzi, was alive when Camicion was telling Dante about him here (1300). Carlino had been given custody of a castle belonging to the White Guelfs at Piantravigne in the Valdarno. According to C.H. Grandgent, this castle also housed a number of White and Ghibelline exiles. In July of 1302, Carlino accepted a bribe from the Florentine Blacks to surrender the castle and many of those inside were brutally slain in the resulting siege. Upon Carlino’s death he will be frozen into the next circle of Cocytus, Antenora, the place for those who betray their party or country.

8. Dante has been on the ice long enough now that his curiosity has turned to horror as he shares the pain of the sinners by his shivering. That the traitorous sinners here have “dogish faces” and that their faces have “turned purple,” amplifies how their sins have dehumanized them. (Recall the earlier allusions to frogs, storks, and goats.) Then, adding a touch of reality with his lack of certainty and his attempts to excuse himself on several levels here, he does it again! He kicks a another traitor in the face—hard, as he says! But, from what he tells us here, one can imagine that the ice was studded with frozen heads everywhere, and walking through all of them must have been a challenge—and an experience he’ll never forget. From the emphasis on the me, we know that the sinner he kicked is not only carrying a grudge, but he tells us what it’s for.

The Poet’s reference to his movement “closer to the weighty center of the universe” is a subtle way of saying that he has moved from Caïna to Antenora, and the sinners here will have committed acts of treachery against their parties and their country. The mention of Montaperti, though, and the fact that the sinner doesn’t want to talk about it, is important for the progress of this canto and, as we’ll see, the identification of this treacherous sinner. Montaperti is a small town east of Siena about 30 miles. It is situated very near the Arbia river, and on September 4, 1260 (five years before Dante was born) it was the scene of a famous battle between the Ghibellines of both Siena and Florence against the Florentine Guelfs. The Guelfs were so badly defeated that, in Canto 10:85f, when Dante is talking with the Ghibelline general, Farinata, he remarks that the slaughter and chaos were so terrible that the Arbia flowed red with the blood of the fallen!

9. Bocca degli Abati was a Florentine Ghibelline. During the Battle of Montaperti noted above, he made it look as if he were fighting with the Guelfs. In this way, he stealthily made his way toward the Guelf standard-bearer and with his sword hacked off the cavalryman’s right hand so that the great flag fell to the ground. In battles at this time, the importance of the standard and its various positions cannot be overestimated as a key signal for troop movements across the battlefield. Unable to see their flag, the Guelf troops were immediately thrown into confusion, and in the chaos that ensued the Sienese and Florentine Ghibellines were victorious over them. Dante, of course, had relatives in that battle, and one can imagine the shock that went through him when he realized that the foul traitor was the man he was speaking to.

10. Like Camicion de’Pazzi earlier, Buoso—not caring about the consequences—identifies everyone around him in a fit of betrayal. Buoso da Durea was from Cremona and was the leader of the Ghibelline party there. When the French troops of Charles of Anjou were on their way south and passing through Lombardy, Manfred, son of the emperor Frederick II, paid Buoso to block the French advance through a certain mountain pass. Buoso pocketed the money, but did nothing. In fact, he also took more money from the French to let them through. In a wicked display of irony, in the Italian text here, Dante has Buoso use the French word argento (silver) instead of the Italian denaro.

Continuing with his list, Buoso names Tesauro dei Beccheria from Pavia next. He was the Abbot of the Benedictine Monastery at Vallombrosia, 25 miles to the east of Florence. He was also the Papal Legate of Pope Alexander IV in Tuscany. Sadly, even the head of a famous monastery could also be guilty of political treachery. In 1258, he was beheaded for intriguing with the Florentine Ghibellines after they had been expelled from the city.

Next comes Gianni Soldianier, a Ghibelline nobleman of Florence. In 1266, after the defeat of Manfred at Benevento (see Note 2 in Canto 28), the Florentine Guelfs rebelled against the Frate Gaudenti (see Canto 23) and the Ghibelline rulers at that time. Betraying his party for personal power and gain, Gianni seized the opportunity and set himself up as the leader of the Guelf rebels who were then victorious over the Ghibellines.

Ganelon figured briefly in Canto 31. His betrayal of Charlemagne led to the death of Roland and the defeat of Charlemagne’s troops at Roncesvalles.

And finally, Buoso ends his treacherous rant with Tebaldello de’Zambrasi of Faenza. In 1274, the Lambertazzi family, Ghibellines of Bologna, fled that city and took refuge in Faenza, some 35 miles to the southeast on the way to Ravenna. On November 13, 1280, in order to take revenge on the Lambertazzi over a petty argument about pigs, he opened the gates of Faenza at dawn and allowed the Guelf enemies of the Lambertazzi refugees to enter the city and kill them.

11. Early in this canto Dante mentioned Thebes and its bad reputation in the ancient world was noted. Here is another story from that wicked city which Dante borrows from Statius’ Thebiad (VIII:740-763). The scene is the battle known as The Seven Against Thebes, also related by the Greek playwright Aeschylus in his great drama of the same name. This was a war for the succession of Oedipus’ throne when his son, Eteocles refused to step down at the end of his allotted term as king. Eteocles’ brother, Polynices, who was designated as the king in alternate years, raised an army from Argos headed by the famous “Seven” warriors who attacked each of the seven gates of Thebes. Tydeus (the father of Diomedes in Canto 26) was one of the Argive warriors attacking the city who fought against Menalippus, one of the city’s defenders. Menalippus mortally wounded Tydeus, but it was Amphiarus (see Canto 20) who mortally wounded Menalippus. As both warriors lay dying, Tydeus called for the head of Menalippus, which Capaneus (Canto 14, the most famous of the Seven) cut off and brought to him. In a dying fit of rage, the gloating Tydeus smashed Menalippus’ head open and began to eat his brains. The only difference between Tydeus and the gorging soul Dante encounters here, he tells us, is that this presently-unnamed soul was more ravenous than Tydeus!

Top of page