Dante's Divine Comedy: Inferno

Canto V

Dante and Virgil descend from the First Circle to the Second. Minos stands at the entrance, judging transgressors and selecting a place in Hell for each of them. The Lustful are eternally tossed upon the 'infernal hurricane'. Virgil answers Dante's question by describing the shades of famous lovers—Semiramis of Assyria, Dido of Carthage, Helen of Troy, Achilles, Paris, Paolo Malatesta and Francesca Da Rimini. Dante is saddened by the story of the last of these.

Thus I descended out of the first circle

Down to the second, that less space begirds,

And so much greater dole, that goads to wailing.

There standeth Minos horribly, and snarls;

Examines the transgressions at the entrance;

Judges, and sends according as he girds him.[1]

I say, that when the spirit evil-born

Cometh before him, wholly it confesses;

And this discriminator of transgressions

Seeth what place in Hell is meet for it;

Girds himself with his tail as many times

As grades he wishes it should be thrust down.

Always before him many of them stand;

They go by turns each one unto the judgment;

They speak, and hear, and then are downward hurled.

"O thou, that to this dolorous hostelry

Comest," said Minos to me, when he saw me,

Leaving the practice of so great an office,

"Look how thou enterest, and in whom thou trustest;

Let not the portal's amplitude deceive thee."

And unto him my Guide: "Why criest thou too?

Do not impede his journey fate-ordained;

It is so willed there where is power to do

That which is willed; and ask no further question."

And now begin the dolesome notes to grow

Audible unto me; now am I come

There where much lamentation strikes upon me.

I came into a place mute of all light,

Which bellows as the sea does in a tempest,

If by opposing winds 'tis combated.

The infernal hurricane that never rests

Hurtles the spirits onward in its rapine;

Whirling them round, and smiting, it molests them.

When they arrive before the precipice,

There are the shrieks, the plaints, and the laments,

There they blaspheme the puissance divine.

I understood that unto such a torment

The carnal malefactors were condemned,

Who reason subjugate to appetite.

And as the wings of starlings bear them on

In the cold season in large band and full,

So doth that blast the spirits maledict;

It hither, thither, downward, upward, drives them;

No hope doth comfort them for evermore,

Not of repose, but even of lesser pain.

And as the cranes go chanting forth their lays,

Making in air a long line of themselves,

So saw I coming, uttering lamentations,[2]

Shadows borne onward by the aforesaid stress.

Whereupon said I: "Master, who are those

People, whom the black air so castigates?"

"The first of those, of whom intelligence

Thou fain wouldst have," then said he unto me,

"The empress was of many languages.

To sensual vices she was so abandoned,

That lustful she made licit in her law,

To remove the blame to which she had been led.

She is Semiramis, of whom we read

That she succeeded Ninus, and was his spouse;

She held the land which now the Sultan rules.[3]

The next is she who killed herself for love,

And broke faith with the ashes of Sichaeus;

Then Cleopatra the voluptuous."[4]

Helen I saw, for whom so many ruthless

Seasons revolved; and saw the great Achilles,

Who at the last hour combated with Love.[5]

Paris I saw, Tristan; and more than a thousand

Shades did he name and point out with his finger,

Whom Love had separated from our life.[6]

After that I had listened to my Teacher,

Naming the dames of eld and cavaliers,

Pity prevailed, and I was nigh bewildered.

And I began: "O Poet, willingly

Speak would I to those two, who go together,

And seem upon the wind to be so light."

And, he to me: "Thou'lt mark, when they shall be

Nearer to us; and then do thou implore them

By love which leadeth them, and they will come."

Soon as the wind in our direction sways them,

My voice uplift I: "O ye weary souls!

Come speak to us, if no one interdicts it."

As turtle-doves, called onward by desire,

With open and steady wings to the sweet nest

Fly through the air by their volition borne,

So came they from the band where Dido is,

Approaching us athwart the air malign,

So strong was the affectionate appeal.

"O living creature gracious and benignant,

Who visiting goest through the purple air

Us, who have stained the world incarnadine,

If were the King of the Universe our friend,

We would pray unto him to give thee peace,

Since thou hast pity on our woe perverse.

Of what it pleases thee to hear and speak,

That will we hear, and we will speak to you,

While silent is the wind, as it is now.

Sitteth the city, wherein I was born,

Upon the sea-shore where the Po descends

To rest in peace with all his retinue.

Love, that on gentle heart doth swiftly seize,

Seized this man for the person beautiful

That was ta'en from me, and still the mode offends me.

Love, that exempts no one beloved from loving,

Seized me with pleasure of this man so strongly,

That, as thou seest, it doth not yet desert me;

Love has conducted us unto one death;

Caina waiteth him who quenched our life!"

These words were borne along from them to us.[7]

As soon as I had heard those souls tormented,

I bowed my face, and so long held it down

Until the Poet said to me: "What thinkest?"

When I made answer, I began: "Alas!

How many pleasant thoughts, how much desire,

Conducted these unto the dolorous pass!"

Then unto them I turned: me, and I spake,

And I began: "Thine agonies, Francesca,

Sad and compassionate to weeping make me.

But tell me, at the time of those sweet sighs,

By what and in what manner Love conceded,

That you should know your dubious desires?"

And she to me: "There is no greater sorrow

Than to be mindful of the happy time

In misery, and that thy Teacher knows.

But, if to recognize the earliest root

Of love in us thou hast so great desire,

I will do even as he who weeps and speaks.

One day we reading were for our delight

Of Lancelot, how Love did him enthrall.

Alone we were and without: any fear.

Full many a time our eyes together drew

That reading, and drove the color from our faces;

But one point only was it that o'ercame us.

When as we read of the much-longed-for smile

Being by such a noble lover kissed,

This one, who ne'er from me shall be divided,

Kissed me upon the mouth all palpitating.

Galeotto was the book and he who wrote it.

That day no farther did we read therein."[8]

And all the while one spirit uttered this,

The other one did weep so, that, for pity,

I swooned away as if I had been dying,

And fell, even as a dead body falls.

Illustrations

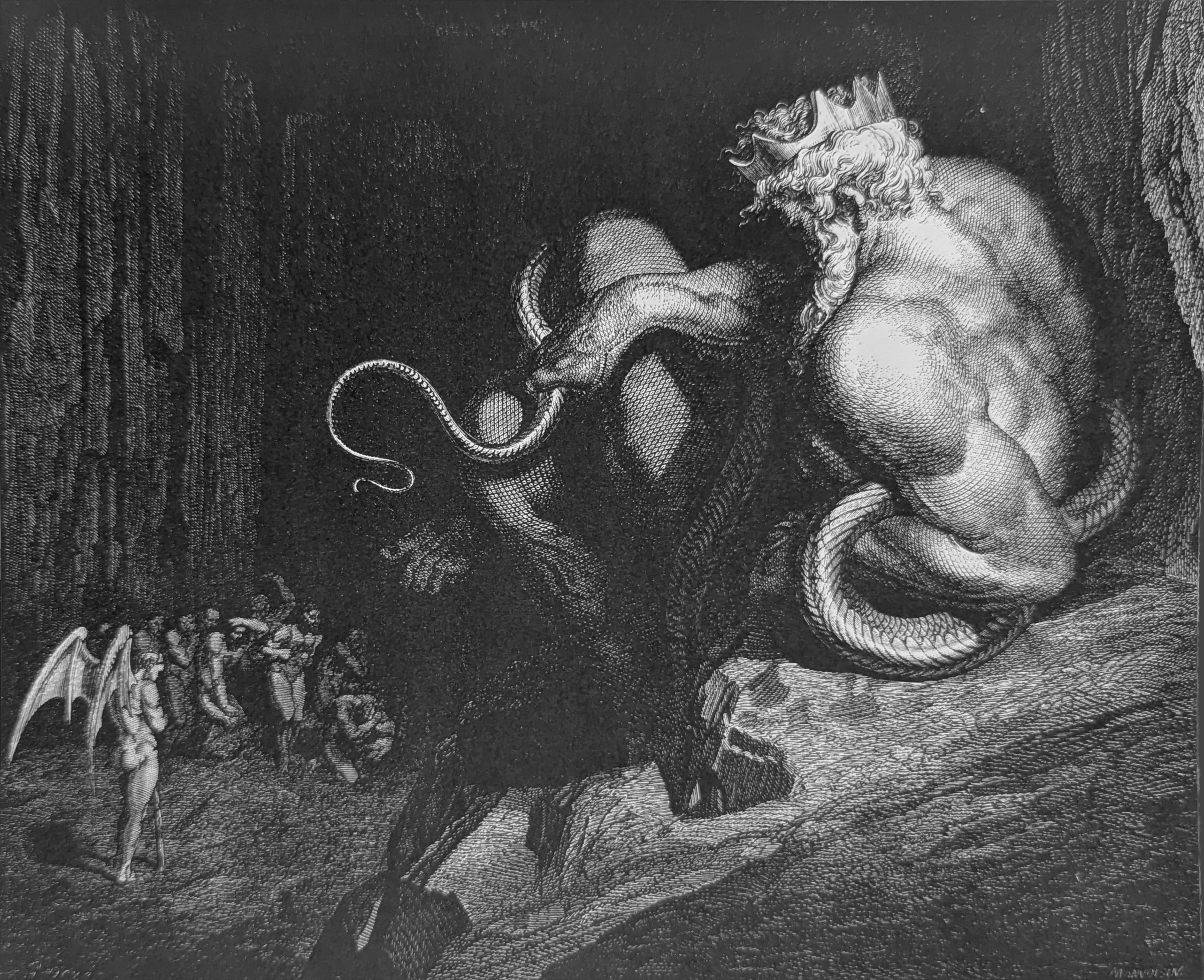

There standeth Minos horribly, and snarls; / Examines the transgressions at the entrance; / Judges, and sends according as he girds him. buf. V. lines 4-6

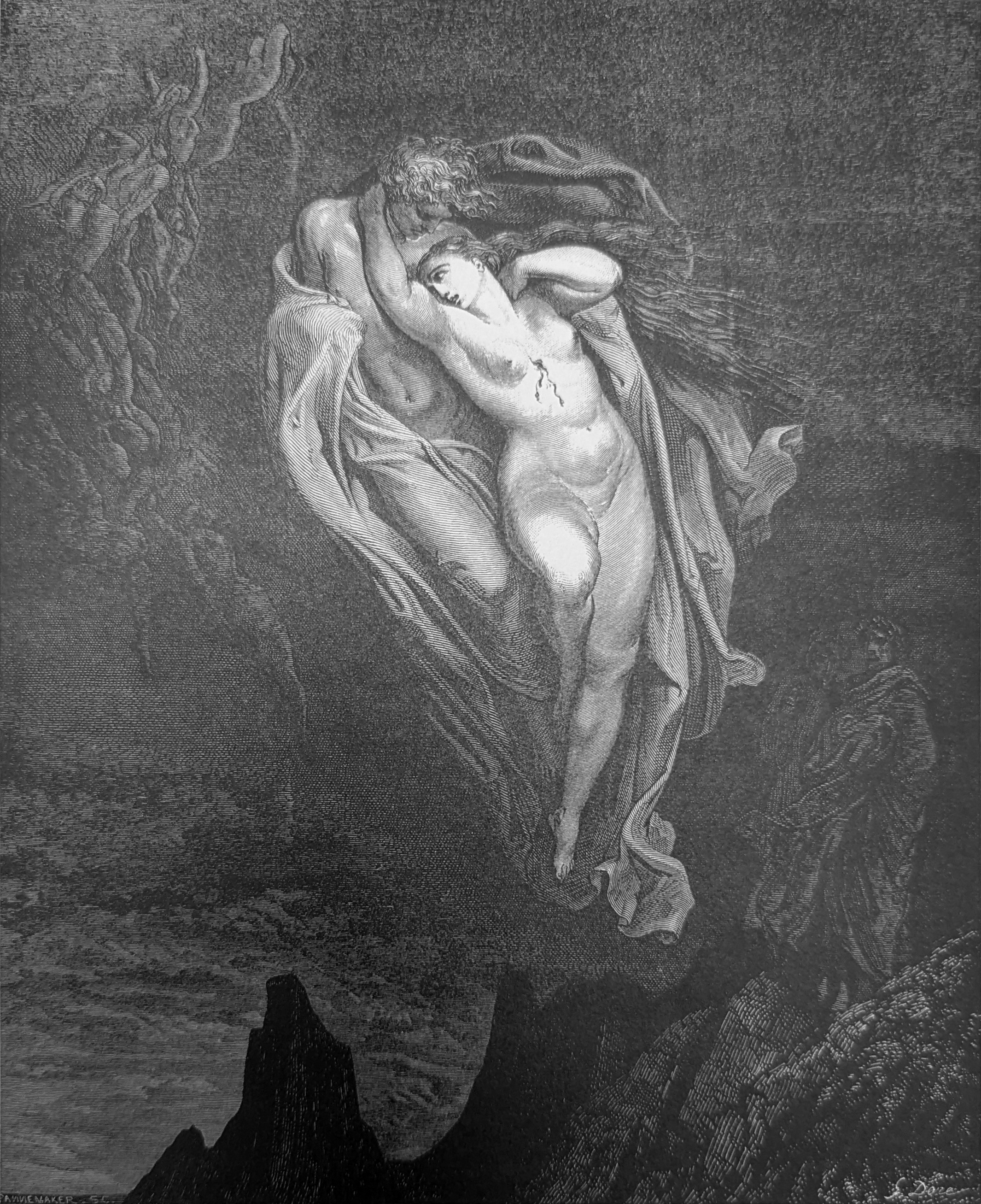

The infernal hurricane that never rests / Hurtles the spirits onward in its rapine; Inf. V, lines 31-32

"O Poet, willingly / Speak would I to those two, who go together,/ And seem upon the wind to be so light." Inf. V, lines 73-75

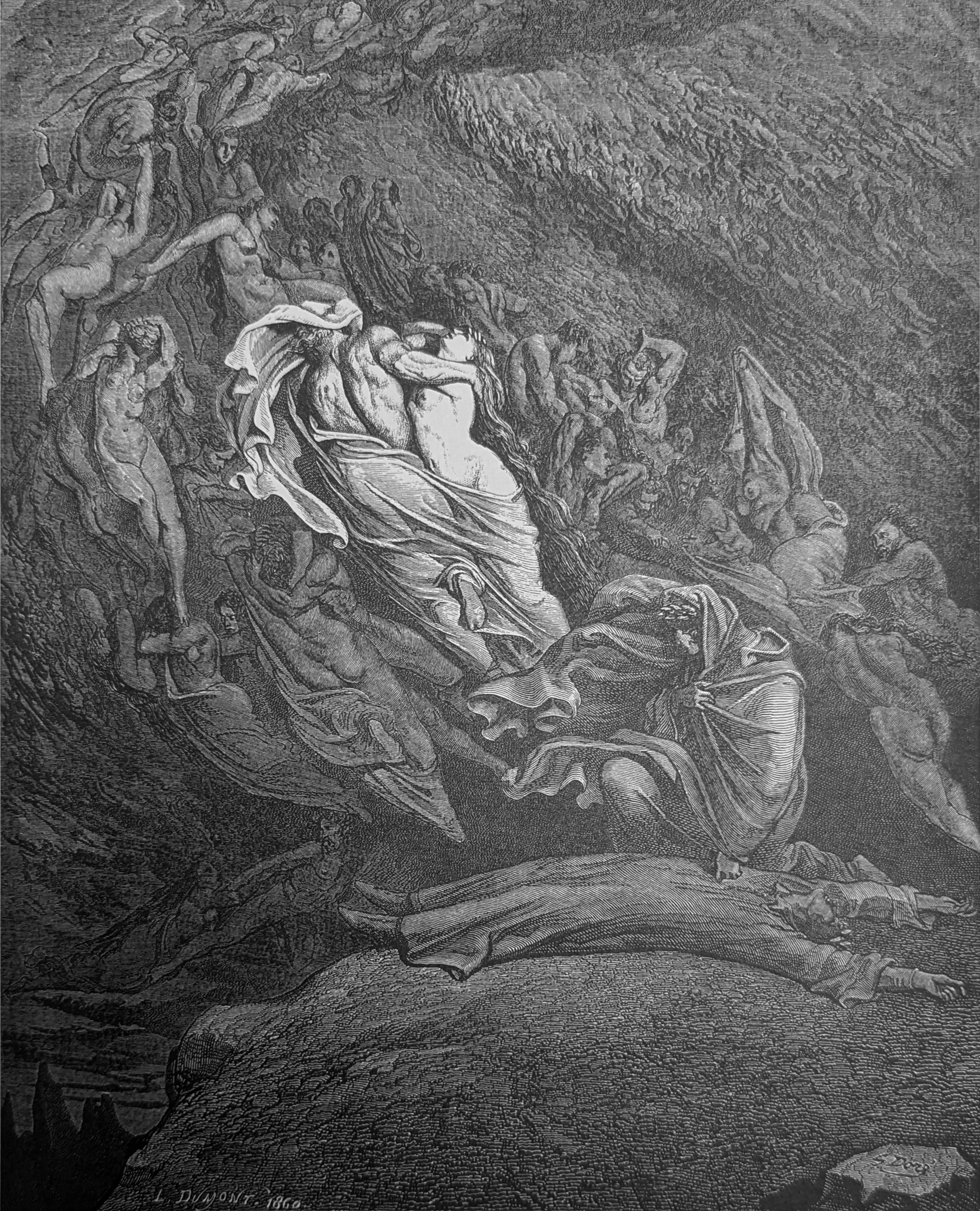

"Love has conducted us unto one death; / Caina waiteth him who quenched our life!" / These words were borne along from them to us. Inf. V, lines 106-108

"That day no farther did we read therein." Inf. V, line 138

I swooned away as if I had been dying, / And fell, even as a dead body falls. Inf. V, lines 141-142

Footnotes

1. Minos was the son of Europa and Zeus. In mythology he became the king of Crete, and was so famous for his wisdom and justice that after he died, he was made judge of the dead when they entered the underworld. A Christian reader might raise an eyebrow at Dante’s use of a pagan mythological figure as the Judge of souls after death, but Dante comfortably and to good purpose makes use of these figures as guardians of various levels of his Inferno. And there will be more!

Dante sets us up for this extended explanation by the earlier mention of Minos’ long tail. First, note how Dante cleverly “monsterizes” his Hell-guardians – in this case with a great serpentine tail. It is pure fantasy on Dante’s part – and it works well – that the judgment of the sinners is rendered by the number of times Minos wraps his tail about his body. The sinners here readily confess just as they readily crowded the shore of the Acheron in Canto 3.

2. Watching the amazing waving patterns of these immense flocks of birds is one of Nature’s awesome sights. Like so many other nature descriptions that Dante will make throughout his poem, one has to believe that he actually saw what he describes. This wonderful spectacle of birds is called murmuration. See this on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eakKfY5aHmY.

3. Dante’s historical source for this information about Semiramis is Paulus Orosius, a 4th century Christian historian and student of St. Augustine. Accustomed as we are nowadays to tabloid sensations, Orosius’ description of Semiramis seems tame, but disgusting enough to put her first on Virgil’s list of Who’s Who in the wind:

“His [Ninus’] wife Semiramis succeeded him on the throne. She had the will of a man and went about dressed like her son. For forty-two years she kept her own people, lusting for blood from their previous taste of it, engaged in the slaughter of foreign tribes. Not satisfied with the boundaries that she had inherited from her husband, who was the only king of that age to be warlike and who had acquired these lands in the course of fifty years, the woman added to her empire Ethiopia, which had been sorely oppressed by war and drenched with blood. She also declared war upon the people of India, a land which nobody ever had penetrated excepting herself and Alexander the Great. To persecute and slaughter peoples living in peace was at that time an even more cruel and serious matter than it is today; for in those days neither the incentive for conquest abroad nor the temptation for the exercise of cupidity at home was so strong. Burning with lust and thirsty for blood, Semiramis in the course of continuous adulteries and homicides caused the death of all those whom she had delighted to hold in her adulterous embrace and whom she had summoned to her by royal command for that purpose. She finally most shamelessly conceived a son, godlessly abandoned the child, later had incestuous relations with him, and then covered her private disgrace by a public crime. For she prescribed that between parents and children no reverence for nature in the conjugal act was to be observed, but that each should be free to do as he pleased.” (Historiae Adversus Paganos 1.4.7-8

4. Sichaeus, in Phoenician mythology, was the husband of Dido, queen of Carthage, whose brother Pygmaion caused him to be murdered for his treasure. The disembodied spirit revealed the place in which the treasure was concealed to the widow and bade her flee. She accordingly landed in Africa, and founded Carthage (Virgil, Aeneid, i, 347, etc.; 4:20, 502, etc.; 6:474). Justin (xviii, 4) gives the name Acerbos to Dido's husband, and states that Pygmalion himself was the murderer; that Dido fled his kingdom in order to escape from the scene which fed her grief, and that she was obliged to use stratagem to induce her attendants to refrain from delivering her up to the king. After touching at Cyprus, the final settlement was made at Carthage.

This is a most brief identification for one of ancient history’s most famous women. Historical accounts about Cleopatra have been glamorized by Shakespeare (Antony and Cleopatra) and the great modern movie spectacles that create a character larger than life and a flash-point in the clash of empires and their heroes. She was the last ruler of Egypt before it was subsumed by the empire of Rome. During an affair with her, Julius Caesar helped rid her of her brother/husband with whom she jointly ruled. Not long afterward, she bore the married Caesar a son. After Caesar’s assassination, she ensnared Mark Antony, and though he was also married with children, the two of them carried on in shameful debauchery until Augustus (then Octavian) invaded Egypt. Trapped and with no other refuge, Mark Antony took his own life and died in his lover’s arms. Not long afterward, Cleopatra followed him in suicide, clasping a deadly asp to her breast. While the manner of her death has dramatic and cinematic appeal, this “snake theory” is hotly contested among scholars who suggest she died by poison in some other manner.

5. The story of Helen, Achilles, and Paris is somewhat complicated, and made more so by different accounts.

Helen of Troy, the title by which the world has come to know her, was the wife of Menelaus, the king of Sparta. This is the Helen whose beautiful face is said to have launched a thousand ships (in the Trojan War). Christopher Marlowe, a contemporary of Shakespeare, wrote a play in 1604 called The Tragical History of Dr. Faustus. In it he writes:

“Was this the face that launched a thousand ships

And burnt the topless towers of Ilium?

Sweet Helen, make me immortal with a kiss…”

In the Roman de Troie, Benoit de Sainte-Maure writes this of Helen: “Because of her, the world has had such trouble; because of her, Greece is so impoverished of her noble knighthood; because of her, the world is worse; because of her, the rich and best are dead, vanquished, and cut to pieces; because of her, kingdoms have been devastated; because of her, Troy is burned and destroyed.”

Paris, son of King Priam of Troy, enters the story because he was given the gorgeous Helen as a gift by Aphrodite for judging a beauty contest among the goddesses. Paris took Helen to Troy where he married her, setting the Trojan War in motion when her husband-king, Menelaus, gathered an army to take her back.

Achilles enters the story having fallen hopelessly in love with Polyxena, whose father was Priam, king of Troy. Desiring to marry her, Achilles is lured to the temple where he thinks the marriage will take place. But there he is ambushed by Paris, who shoots him in the (famous Achilles’) heel with an arrow. As noted previously, Dante did not know Greek, so he did not read Homer. Most likely, his knowledge of these characters and the larger epic to which they belong came from versions of the story that were popular in the Middle Ages.

6. With even less identifying information than Cleopatra, Dante assumed that his readers were familiar with Tristan and his lover, Isolde, who were famous characters in Medieval romances. There are numerous versions of this sad tale. Common to most versions, it seems that Tristan’s uncle, King Mark of Cornwall, was engaged to the Irish princess Isolde. Sent by Mark to bring her to England, Tristan and Isolde fell in love and continued their secret affair even after she was married to the king. In one version, Tristan is hit by a poisoned arrow and dies a long, slow death, during which Isolde is summoned. After a harrowing voyage she arrives just in time to lay alongside her lover and expire with him. Another version has it that though they thought they had hidden their assignations, the king found them out and killed Tristan in flagrante delicto.

7. Caïna is an area at the very bottom of hell reserved for those who treacherously betrayed members of their own family. The name is derived from Cain who, in chapter four of the Book of Genesis, killed his brother. If one were looking for the smallest bit of fun in this otherwise dark episode, it’s this: we have probably forgotten that there are two Dante’s. One can assume that Dante the Pilgrim had no idea what Francesca was talking about when she spoke about Caïna. Well, someplace very bad, for sure. But one might presume that when Dante the Poet set about writing the Inferno he had this first part of his great poem pretty much mapped out, perhaps in an outline or a summary, and had already created and named this place called Caïna.

8. Dante uses the word Galeotto here. This is the character Gallehault in the story of Lancelot and Guinevere, and it was he who introduced the famous knight to Queen Guinevere. Their resulting adultery tore asunder the court of King Arthur and the brotherhood of the Knights of the Round Table. The delicacy of Francesca’s confession to Dante is itself torn asunder as Francesca blames her adultery with Paolo not only the book, but on the one who wrote it as well. One might be tempted to ask, “How ridiculous can you get!” But we must remember that Francesca is completely serious and convinced of their innocence. And, what’s worse, as we shall see, Dante is completely taken in by her. (Were you?) Once again, as will be seen many more times in the Inferno, the sinners blame everyone and everything for their sins.

Top of page