Dante's Divine Comedy: Inferno

Canto XXVIII

In the ninth bolgia, the large crowds of the Sowers of Discord are disfigured and dismembered, many with their intestines spilling out. Several instigators of scandal and schism are named, including the Prophet Mahomet, founder of Islam, split open from crotch to chin, and Ali, his son-in-law. The sinners curse their lot and stir Dante's pity before predicting the unsavory end of certain Italians who are still alive. The image of the medieval French troubadour Bertram De Born carrying his decapitated head in his hand is a vivid example of Dantean divine retribution or contrapasso, where his wits are literally separated from his body.[1]

Who ever could, e'en with untrammelled words,

Tell of the blood and of the wounds in full

Which now I saw, by many times narrating?

Each tongue would for a certainty fall short

By reason of our speech and memory,

That have small room to comprehend so much.

If were again assembled all the people

Which formerly upon the fateful land

Of Puglia were lamenting for their blood[2]

Shed by the Romans and the lingering war

That of the rings made such illustrious spoils,

As Livy has recorded, who errs not,[3]

With those who felt the agony of blows

By making counter-stand to Robert Guiscard,

And all the rest, whose bones are gathered still[4]

At Ceperano, where a renegade

Was each Apulian, and at Tagliacozzo,

Where without arms the old Alardo conquered,[5]

And one his limb transpierced, and one lopped off,

Should show, it would be nothing to compare

With the disgusting mode of the ninth _Bolgia_.

A cask by losing center-piece or cant

Was never shattered so, as I saw one

Rent from the chin to where one breaketh wind.

Between his legs were hanging down his entrails;

His heart was visible, and the dismal sack

That maketh excrement of what is eaten.

While I was all absorbed in seeing him,

He looked at me, and opened with his hands

His bosom, saying: "See now how I rend me;

How mutilated, see, is Mahomet;

In front of me doth Ali weeping go,

Cleft in the face from forelock unto chin;[6]

And all the others whom thou here beholdest,

Disseminators of scandal and of schism

While living were, and therefore are cleft thus.

A devil is behind here, who doth cleave us

Thus cruelly, unto the falchion's edge

Putting again each one of all this ream,

When we have gone around the doleful road;

By reason that our wounds are closed again

Ere any one in front of him repass.

But who art thou, that musest on the crag,

Perchance to postpone going to the pain

That is adjudged upon thine accusations?"

"Nor death hath reached him yet, nor guilt doth bring him,"

My Master made reply, "to be tormented;

But to procure him full experience,

Me, who am dead, behooves it to conduct him

Down here through Hell, from circle unto circle;

And this is true as that I speak to thee."

More than a hundred were there when they heard him,

Who in the moat stood still to look at me,

Through wonderment oblivious of their torture.

"Now to Fra Dolcino, then, to arm him,

Thou, who perhaps wilt shortly see the sun,

If soon he wish not here to follow me,[7]

So with provisions, that no stress of snow

May give the victory to the Novarese,

Which otherwise to gain would not be easy."

After one foot to go away he lifted,

This word did Mahomet say unto me,

Then to depart upon the ground he stretched it.

Another one, who had his throat pierced through,

And nose cut off close underneath the brows,

And had no longer but a single ear,[8]

Staying to look in wonder with the others,

Before the others did his gullet open,

Which outwardly was red in every part,

And said: "O thou, whom guilt doth not condemn,

And whom I once saw up in Latian land,

Unless too great similitude deceive me,

Call to remembrance Pier da Medicina,

If e'er thou see again the lovely plain

That from Vercelli slopes to Marcabo,[9]

And make it known to the best two of Fano,

To Messer Guido and Angiolello likewise,

That if foreseeing here be not in vain,[10]

Cast over from their vessel shall they be,

And drowned near unto the Cattolica,

By the betrayal of a tyrant fell.

Between the isles of Cyprus and Majorca

Neptune ne'er yet beheld so great a crime,

Neither of pirates nor Argolic people.

That traitor, who sees only with one eye,

And holds the land, which some one here with me

Would fain be fasting from the vision of,[11]

Will make them come unto a parley with him;

Then will do so, that to Focara's wind

They will not stand in need of vow or prayer."

And I to him: "Show to me and declare,

If thou wouldst have me bear up news of thee,

Who is this person of the bitter vision."

Then did he lay his hand upon the jaw

Of one of his companions, and his mouth

Oped, crying: "This is he, and he speaks not.

This one, being banished, every doubt submerged

In Caesar by affirming the forearmed

Always with detriment allowed delay."

O how bewildered unto me appeared,

With tongue asunder in his windpipe slit,

Curio, who in speaking was so bold!

And one, who both his hands dissevered had,

The stumps uplifting through the murky air,

So that the blood made horrible his face,

Cried out: "Thou shalt remember Mosca also,

Who said, alas! 'A thing done has an end!'

Which was an ill seed for the Tuscan people."[12]

"And death unto thy race," thereto I added;

Whence he, accumulating woe on woe,

Departed, like a person sad and crazed.

But I remained to look upon the crowd;

And saw a thing which I should be afraid,

Without some further proof, even to recount,

If it were not that conscience reassures me,

That good companion which emboldens man

Beneath the hauberk of its feeling pure.[13]

I truly saw, and still I seem to see it,

A trunk without a head walk in like manner

As walked the others of the mournful herd.

And by the hair it held the head dissevered,

Hung from the hand in fashion of a lantern,

And that upon us gazed and said: "O me!"

It of itself made to itself a lamp,

And they were two in one, and one in two;

How that can be, He knows who so ordains it.

When it was come close to the bridge's foot,

It lifted high its arm with all the head,

To bring more closely unto us its words,

Which were: "Behold now the sore penalty,

Thou, who dost breathing go the dead beholding;

Behold if any be as great as this.

And so that thou may carry news of me,

Know that Bertram de Born am I, the same

Who gave to the Young King the evil comfort.[14]

I made the father and the son rebellious;

Achitophel not more with Absalom

And David did with his accursed goadings.

Because I parted persons so united,

Parted do I now bear my brain, alas!

From its beginning, which is in this trunk.

Thus is observed in me the counterpoise."

Illustrations

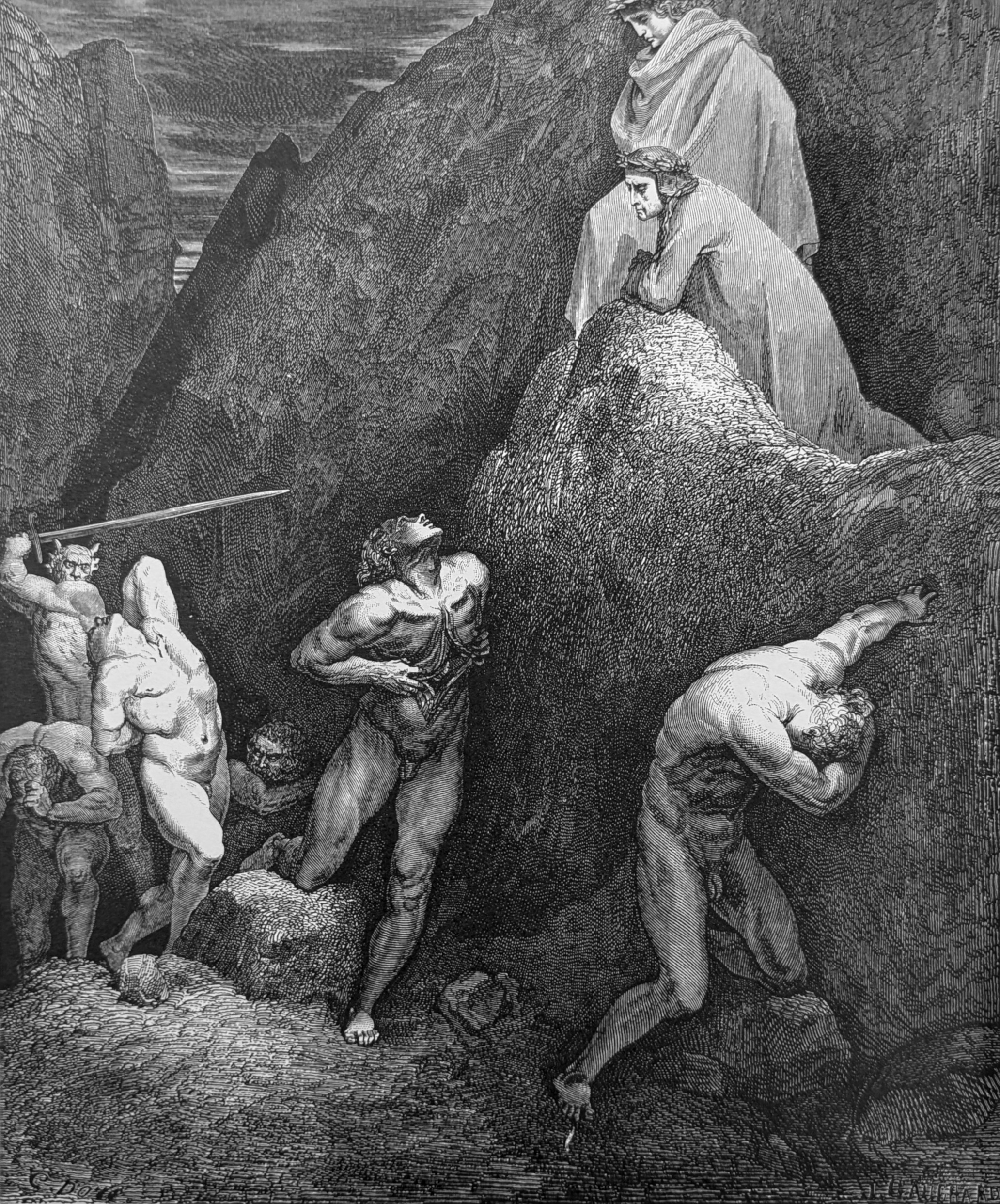

He looked at me, and opened with his hands / His bosom, saying: "See now how I rend me;" Inf. XXVIII, lines 29-30

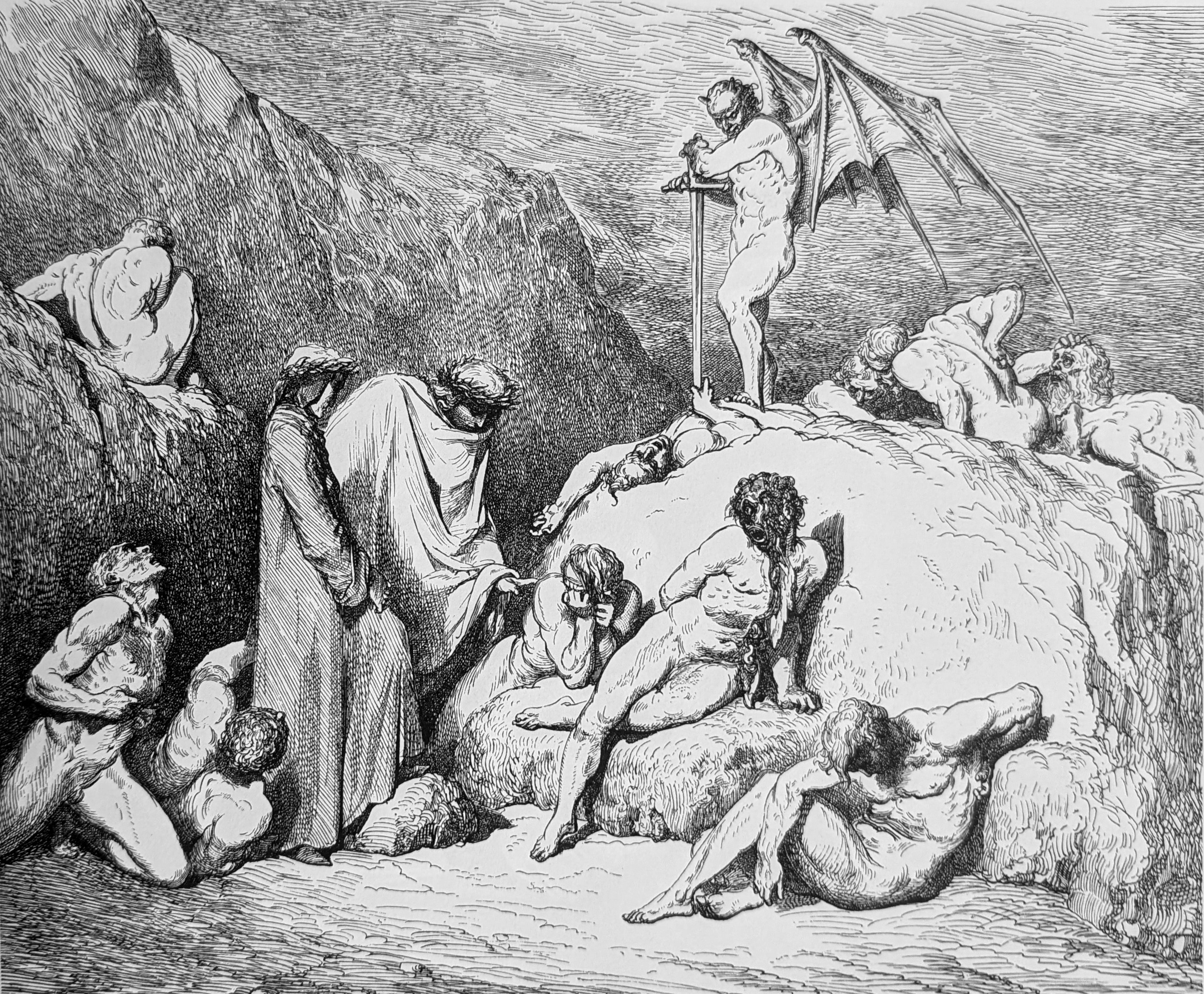

"Call to remembrance Pier da Medicina," Inf. XXVIII, lines 73

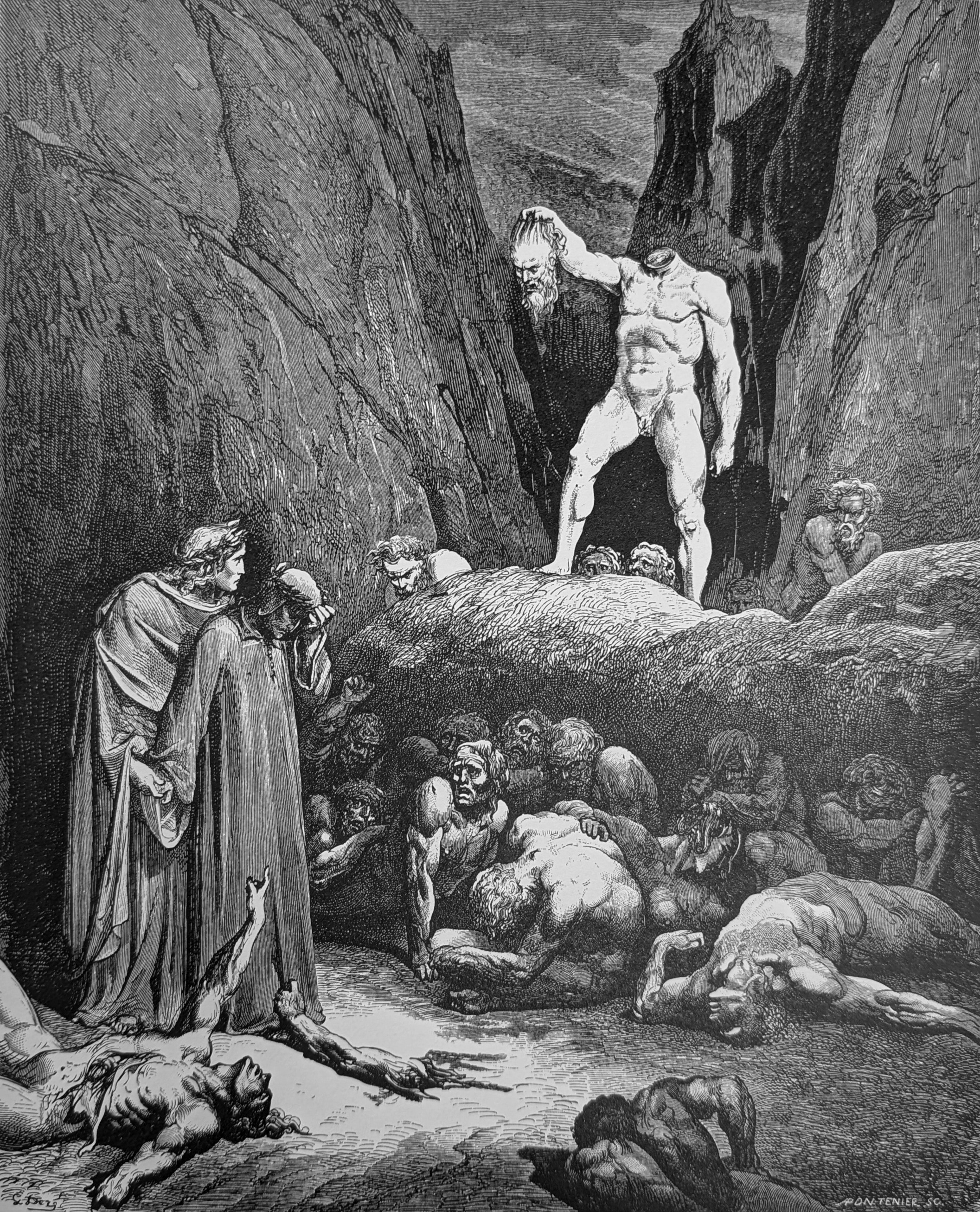

By the hair it held the head dissevered, / Hung from the hand in fashion of a lantern, / And that upon us gazed and said: "O me!" Inf. XXVIII, lines 121-123

Footnotes

1. Troubador, Occitan, trobar, “to find”, meaning a traveling minstrel.

2. Puglia (modern Apulia) is the southeastern region of Italy bordering the Adriatic and including the “heel” of the “boot.” The first battle Dante notes here is the long war of almost 150 years between the ancient Samnites (inhabitants of roughly the same are a as Puglia) and the Romans (434-290 B.C.).

3. The second battle, with its reference to the rings of the dead, is the Second Punic (Carthaginian) War (218-201 B.C.) in which the Roman army was dealt a smashing defeat by Hannibal at Cannae along the central coast of Puglia in 216 B.C. The Roman historian Livy notes a loss of life in the tens of thousands, and that following the battle, Hannibal returned to Carthage and presented its senate with three bushels of gold rings taken from the fingers of dead Roman soldiers. Another estimate lists the number of dead in this battle alone at 65,000!

4. The third “battle” is actually a reference to several battles of the famous Norman adventurer and Duke of Apulia, Robert Guiscard. Dante most likely includes him here because he won fame for his defeats against the Saracen and Greek invaders among others. W e will meet him again in Canto 18 of the Paradiso where Dante places him among the great warriors of the faith.

5. The fourth battle is referenced by the town of Ceprano, midway between Rome and Naples. Ceprano was the location of one of several mountain passes guarded by the troops of Manfred, King of Sicily and son of Frederick II, against the advances of Charles of Anjou. Those guarding the pass betrayed Manfred and deserted their posts. Charles and his forces soon defeated and killed Manfred at the Battle of Benevento in 1266. Benevento is an ancient city situated about 45 miles east of Naples. Dante apparently conflates the treachery at Ceprano and the Battle of Benevento. We will meet Manfred in Canto 3 of the Purgatorio as an outstanding example of God’s mercy.

Dante ends this “piling on” of battles and bodies with a reference to Tagliacozzo, a town about half way between Rome and the Adriatic coast. In 1268 the forces of Charles of Anjou (again) and those of Conradin, nephew of Manfred, met at Tagliacozzo. The victory of Charles was credited to the clever strategy of Alardo (Érard de Valéry), his general. The plan was for Charles to keep a reserve force ready but hidden. When Conradin seemed to be winning and his army started to scatter, Alardo brought out his reserves and won the battle for Charles. Conradin escaped the defeat but was later captured and executed.

6. The first two subjects of his observations are Mohammed, the prophet and founder of Islam, and his son-in-law and first disciple, Ali. (In all, this canto will feature three religious figures and five of them political.) Modern readers are all too familiar with the graphic violence served up by Hollywood, but Dante was well ahead of his time here, especially in the genre of “slasher movies.” Both men are slashed horribly, Mohammed (who identifies himself without being questioned) obviously the worst of the two. Botticelli illustrates this scene with yards of Mohammed’s intestines trailing out behind him as he walks! This is really the most graphic canto in the Inferno, and the Poet minces no words in creating another fitting contrapasso of horror and disgust–-a kind of human abattoir.

An interesting fact to consider about Mohammed is that in the Middle Ages he was considered a schismatic and an apostate, not necessarily a heretic. Some believed that he was originally a Christian, even a priest or a cardinal, and broke from the faith to found a new religion in the Near East. Dante places him here among those who caused great and famous divisions – in this case, a great religious divide in the world at that time. Hollander states that Dante saw the prophet not as the founder of a new religion but of a rival religion. Though already mutilated, when Mohammed sees Dante he literally tears himself more widely open as he explains the contrapasso. The Poet’s vulgar language is intentional as it projects a response of disgust and subtly allows the Poet to debase what the prophet had done in the most terrible way possible.

7. Clear now that Dante is, in fact, alive, Mohammed asks him to deliver a message to a more contemporary religious renegade, Fra Dolcino. We remember, of course, that the spirits can see the past and the future, while the present is not clear. But it’s curious why such an old schismatic would have concern for one living 600 years later, except – cleverly – since he was a prophet, Dante the Poet has him deliver a prophecy to the Pilgrim. Musa offers the following suggestion:

“Mahomet’s ‘warning’ to Fra Dolcino seems based on the fact that their religious activities, modifying existing religious institutions, eventually led to splits within the universal church: Mahomet impeded the possibility of a single, unified religion, while Fra Dolcino caused a split within the Catholic faith.”

The story of Fra Dolcino takes place at a time in the Middle Ages that saw the rise and fall of several fanatical and apocalyptic religious sects seeking to reform the Church. In this case, once the founder of The Apostolic Brethren (one of these sects) was burned at the stake in 1260, Dolcino took over the leadership of this group of Franciscan-like monks, though they had no connection with that Order. He himself was not a monk but the illegitimate son of a priest. He was intelligent, eloquent, and given to apocalyptic prophecies. His Order’s members preached simplicity and a return to the Church of apostolic times. The Rule of the order claimed, among other things the sharing of property and of women! One can understand what came next. Pope Clement V declared the group heretical and called a crusade against them to wipe them out. Dolcino took his order, including its women and, apparently, several thousand followers, into hiding at a stronghold in the mountainous region between Novara and Vercelli (between Milan and Turin). There they staved off the papal forces for more than a year until they were finally starved out. In the spring of 1307, Fra Dolcino and his supposed mistress, Margarita of Trent, were captured. At Vercelli, she was slowly burned at the stake i n the sight of Dolcino, after which he was paraded through the streets and horribly tortured and maimed along the route back to the stake, where he was thrown upon the fire that still consumed the body of his paramour. Dante, of course, was in exile at this time.

8. In keeping with the ghoulishness of the scene, Pier, with his throat cut, and his nose and one ear cut off, introduces Curio by pulling his mouth open and speaking for him—because his tongue has been cut off! This former Roman Tribune, Caius Scribonius Curio, is one of those side-lined characters in history who are all but forgotten in the aftermath of the upheaval they caused. In this case, it was he who urged Julius Caesar to cross the Rubicon River (about 12 miles north of Rimini) with his troops who we re gathered there, and begin his fateful march on Rome. At that time, the Rubicon marked the northern boundary of the Republic of Rome. Caesar, who had been governor of the area north of this boundary had been forbidden to cross it with his army. Curio was apparently a gifted orator (another possible reason for having his tongue cut out) and earlier in his career was actually an enemy of Caesar. However, it is said that some time before the river crossing, Caesar paid all of Curio’s debts and also paid for hi s support in Rome. Thereafter, the two were of one mind, and the rest is history. Curio’s advice, “A man who’s ready is lost if he waits,” would be matched by Caesar’s famous words the following day, January 10, 49 B.C.: “The die is cast.”

9. Cleverly, this almost faceless sinner recognizes Dante by his face, and he’ll ask Dante to recall him by giving his name – Pier da Medicina—since his face is so mutilated. Medicina is a town about 20 miles east of Bologna, and it is not known how Dante ma y have known this sinner. And apart from Dante, while little is known of this man, what remains was unsavory: he fomented scandals, sowed suspicion, was a liar, and he instigated feuds—most notably between the Polenta family in Ravenna and the Malatesta family in Rimini. All of this is quite enough to place him here in this bolgia. Very cleverly, without listing these sins, he bears the marks of them as Vernon notes in his commentary:

“Pier da Medicina is pierced through the throat, from which issued so many lies; he has been deprived of the use of the nose he was so fond of thrusting into other people’s affairs; and he is represented with one ear only, as he did not use both to listen t o the evil and the good and to distinguish between them; and thus maimed and disfigured he appears in his torment as repulsive an object, as in his life he had appeared insidiously attractive and handsome.”

The references to Vercelli (between Turin and Milan) and Marcabò (a castle/fortress at the mouth of the Po River north of Ravenna), mark the far western and far eastern boundaries of the Po River Valley (about 200 miles, which Pier calls the “beautiful plains”) in the old region of Romagna, now Emilia-Romagna.

10. After this bit of geography, Pier gives Dante a terrible prophecy to deliver. First, another bit of geography. Rimini (recall Canto 5 and Francesca da Rimini, and the Malatesta family she married into) sits on the Adriatic coast 30 miles south of Ravenna. Fano is farther south about 60 miles. Virtually between Rimini and Fano lies the town of Cattolica. Between Cattolica and south to Fano are high coastal headlands from which perilous winds rush down on the sea, forcing mariners to use extreme caution along that region of the Adriatic coast. Over the centuries, commentators are not sure where (except from Pier) Dante got the wicked story Pier reports/prophesies. It seems that two important citizens of Fano (Guido del Cassero and Angiolello di Carignano) were summoned to a meeting at Cattolica by Malatestino, the wicked lord of Rimini (Francesca’s other brother-in-law). Traveling from Fano to Cattolica by sea, their ship was intercepted by Malatestino's henchmen, who boarded their ship and murdered them by stuffing them into rock-filled sacks and throwing them into the sea. Malatestino’s motive was to take control of the town of Fano, which he eventually did. He was referred to by Dante in the previous canto when he gave Guido da Montefeltro his “report” about Romagna.

11. Finally, in a kind of jump-forward-jump-backward reference, Pier makes an oblique segue to the next sinner, whom he’ll introduce in a moment. This new schismatic will be from Rimini which, as Pier is talking, is ruled by Malatestino, the “one-eyed tyrant.” Pier ends by telling Dante that Malatesta will have the two nobles from Fano drowned before they have time to say the traditional sailors’ prayer for protection against the winds off the headlands of Focara (near Cattolica on Italy’s east coast between Rimini and Pesaro).

12. All through the Inferno, and the entire Poem, for that matter, we have heard about and seen the results of the incessant battles between the Guelf and Ghibelline parties. Dante the Poet and many of his characters have and will comment about it and the destruction to the social fabric of Florence caused by this feuding. Recall how, in Canto 6, Dante asked Ciacco about the whereabouts of five worthy Florentines who were intent on doing good. Ciacco remarked that they were among the blacker souls below. The last one mentioned there by Ciacco was Mosca. Here, at last, we meet the man—Mosca de’Lamberti—who brought the embers of enmity to full flame—and caused what Musa calls “the slow suicide of Florence.”

Here is the story. In 1215, 40 years before Dante was born, during a banquet celebrating the knighthood of a young Florentine, one of the guests, Buondelmonte de’ Buondelmonti, a rich, handsome young man, stabbed a rival in the arm. In restitution for the injury and dishonor, the elders decided that young Buondelmonte should wed a girl from the Amidei family. With that agreed to, the powerful Amidei and Buondelmonti families arranged an engagement ceremony, where Buondelmonte was to publicly pledge to marry t he Amidei girl. With the Amidei assembled in the piazza, the young Buondelmonte rode past them, and instead asked for the hand of a girl from the Donati family. Furious, the Amidei and their allies plotted revenge. They debated whether they should scar Buon delmonte’s face, beat him up, or kill him. Mosca de’ Lamberti took the floor and argued that they should kill him at the place where he had dishonored them and get it over with (“What’s done is done!”). Not satisfied with a mere scarring of the face or a beating, we find Mosca here scarred and beaten, as it were, and moving about with his hands cut off!

13. Hauberk, a type of mail worn in battle.

14. Bertran de Born (1140-1215), a Provençal nobleman, was famous as a warrior and a troubadour (a fascinating combination). Much of his poetry focused on themes of military adventure. In his De Vulgari Eloquentia, Dante praises him as one of the most gifted martial poets. According to biographers, while he was accomplished on many levels, he had a penchant for dividing people who were otherwise friends. This was his sin, and his contrapasso will be a logical outcome.

Bertran tells Dante and Virgil that he instigated a quarrel between Henry II of England and his son, Prince Henry. There isn’t a lot of historical background related to this quarrel, and Dante may have relied for much of his information here on Provençal stories circulating at the time. In his confession, Bertran makes himself out to be worse than Achitophel and Absalom (see the story in 2 Samuel 15-17). Absalom was King David’s second son, and Achitophel was one of David’s counselors, but an evil one. He sup ported Absalom when he revolted against his father. When Absalom’s troops were routed by those of his father, he fled through a forest where his long hair became entangled in the branches while his mount kept going. The rebel prince was soon killed by Joab, one of David’s generals. Interestingly, like Guido da Montefeltro in the previous canto, Bertran died as a monk at the Cistercian monastery of Dalon near his castle in southwestern France.

Top of page