Dante's Divine Comedy: Inferno

Canto XXIV

Teacher and pupil begin their arduous ascent of the fallen bridge. Crossing back into the seventh bolgia, they hear sounds in the darkness. Once at the top, Dante cannot catch his breath. At the edge of the eighth bolgia, they behold a chaotic scene of running Thieves being attacked by serpents. One reptile darts out and strikes a blow to a sinner's neck. He catches fire and turns into a pile of ashes before being restored to his mortal form—that of Vanni Fucci, a sacristy thief from Pistoia. He, too, predicts political strife for Florence.

In that part of the youthful year wherein

The Sun his locks beneath Aquarius tempers,

And now the nights draw near to half the day,[1]

What time the hoar-frost copies on the ground

The outward semblance of her sister white,

But little lasts the temper of her pen,

The husbandman, whose forage faileth him,

Rises, and looks, and seeth the champaign

All gleaming white, whereat he beats his flank,

Returns in doors, and up and down laments,

Like a poor wretch, who knows not what to do;

Then he returns and hope revives again,

Seeing the world has changed its countenance

In little time, and takes his shepherd's crook,

And forth the little lambs to pasture drives.

Thus did the Master fill me with alarm,

When I beheld his forehead so disturbed,

And to the ailment came as soon the plaster.

For as we came unto the ruined bridge,

The Leader turned to me with that sweet look

Which at the mountain's foot I first beheld.

His arms he opened, after some advisement

Within himself elected, looking first

Well at the ruin, and laid hold of me.

And even as he who acts and meditates,

For aye it seems that he provides beforehand,

So upward lifting me towards the summit

Of a huge rock, he scanned another crag,

Saying: "To that one grapple afterwards,

But try first if 'tis such that it will hold thee."

This was no way for one clothed with a cloak;

For hardly we, he light, and I pushed upward,

Were able to ascend from jag to jag.

And had it not been, that upon that precinct

Shorter was the ascent than on the other,

He I know not, but I had been dead beat.

But because Malebolge tow'rds the mouth

Of the profoundest well is all inclining,

The structure of each valley doth import

That one bank rises and the other sinks.

Still we arrived at length upon the point

Wherefrom the last stone breaks itself asunder.

The breath was from my lungs so milked away,

When I was up, that I could go no farther,

Nay, I sat down upon my first arrival.

"Now it behooves thee thus to put off sloth,"

My Master said; "for sitting upon down,

Or under quilt, one cometh not to fame,

Withouten which whoso his life consumes

Such vestige leaveth of himself on Earth,

As smoke in air or in the water foam.

And therefore raise thee up, o'ercome the anguish

With spirit that o'ercometh every battle,

If with its heavy body it sink not.

A longer stairway it behoves thee mount;

'Tis not enough from these to have departed;

Let it avail thee, if thou understand me."

Then I uprose, showing myself provided

Better with breath than I did feel myself,

And said: "Go on, for I am strong and bold."

Upward we took our way along the crag,

Which jagged was, and narrow, and difficult,

And more precipitous far than that before.

Speaking I went, not to appear exhausted;

Whereat a voice from the next moat came forth,

Not well adapted to articulate words.

I know not what it said, though o'er the back

I now was of the arch that passes there;

But he seemed moved to anger who was speaking.

I was bent downward, but my living eyes

Could not attain the bottom, for the dark;

Wherefore I: "Master, see that thou arrive

At the next round, and let us descend the wall;

For as from hence I hear and understand not,

So I look down and nothing I distinguish."

"Other response," he said, "I make thee not,

Except the doing; for the modest asking

Ought to be followed by the deed in silence."

We from the bridge descended at its head,

Where it connects itself with the eighth bank,

And then was manifest to me the _Bolgia_;

And I beheld therein a terrible throng

Of serpents, and of such a monstrous kind,

That the remembrance still congeals my blood

Let Libya boast no longer with her sand;

For if Chelydri, Jaculi and Phareae

She breeds, with Cenchri and with Amphisbaena,[2]

Neither so many plagues nor so malignant

E'er showed she with all Ethiopia,

Nor with whatever on the Red Sea is!

Among this cruel and most dismal throng

People were running naked and affrighted.

Without the hope of hole or heliotrope.

They had their hands with serpents bound behind them;

These riveted upon their reins the tail

And head, and were in front of them entwined.

And lo! at one who was upon our side

There darted forth a serpent, which transfixed him

There where the neck is knotted to the shoulders.

Nor 'O' so quickly e'er, nor 'I' was written,

As he took fire, and burned; and ashes wholly

Behooved it that in falling he became.

And when he on the ground was thus destroyed,

The ashes drew together, and of themselves

Into himself they instantly returned.

Even thus by the great sages 'tis confessed

The phoenix dies, and then is born again,

When it approaches its five-hundredth year;[3]

On herb or grain it feeds not in its life,

But only on tears of incense and amomum,

And nard and myrrh are its last winding-sheet.[4]

And as he is who falls, and knows not how,

By force of demons who to earth down drag him,

Or other oppilation that binds man,

When he arises and around him looks,

Wholly bewildered by the mighty anguish

Which he has suffered, and in looking sighs;

Such was that sinner after he had risen.

Justice of God! O how severe it is,

That blows like these in vengeance poreth down!

The Guide thereafter asked him who he was;

Whence he replied: "I rained from Tuscany

A short time since into this cruel gorge.

A bestial life, and not a human, pleased me,

Even as the mule I was; I'm Vanni Fucci,

Beast, and Pistoia was my worthy den."[5]

And I unto the Guide: "Tell him to stir not,

And ask what crime has thrust him here below,

For once a man of blood and wrath I saw him."

And the sinner, who had heard, dissembled not,

But unto me directed mind and face,

And with a melancholy shame was painted.

Then said: "It pains me more that thou hast caught me

Amid this misery where thou seest me,

Than when I from the other life was taken.

What thou demandest I cannot deny;

So low am I put down because I robbed

The sacristy of the fair ornaments,

And falsely once 'twas laid upon another;

But that thou mayst not such a sight enjoy,

If thou shalt e'er be out of the dark places,

Thine ears to my announcement ope and hear:

Pistoia first of Neri groweth meager;

Then Florence doth renew her men and manners;[6]

Mars draws a vapor up from Val di Magra,

Which is with turbid clouds enveloped round,

And with impetuous and bitter tempest[7]

Over Campo Picen shall be the battle;

When it shall suddenly rend the mist asunder,

So that each Bianco shall thereby be smitten.

And this I've said that it may give thee pain."

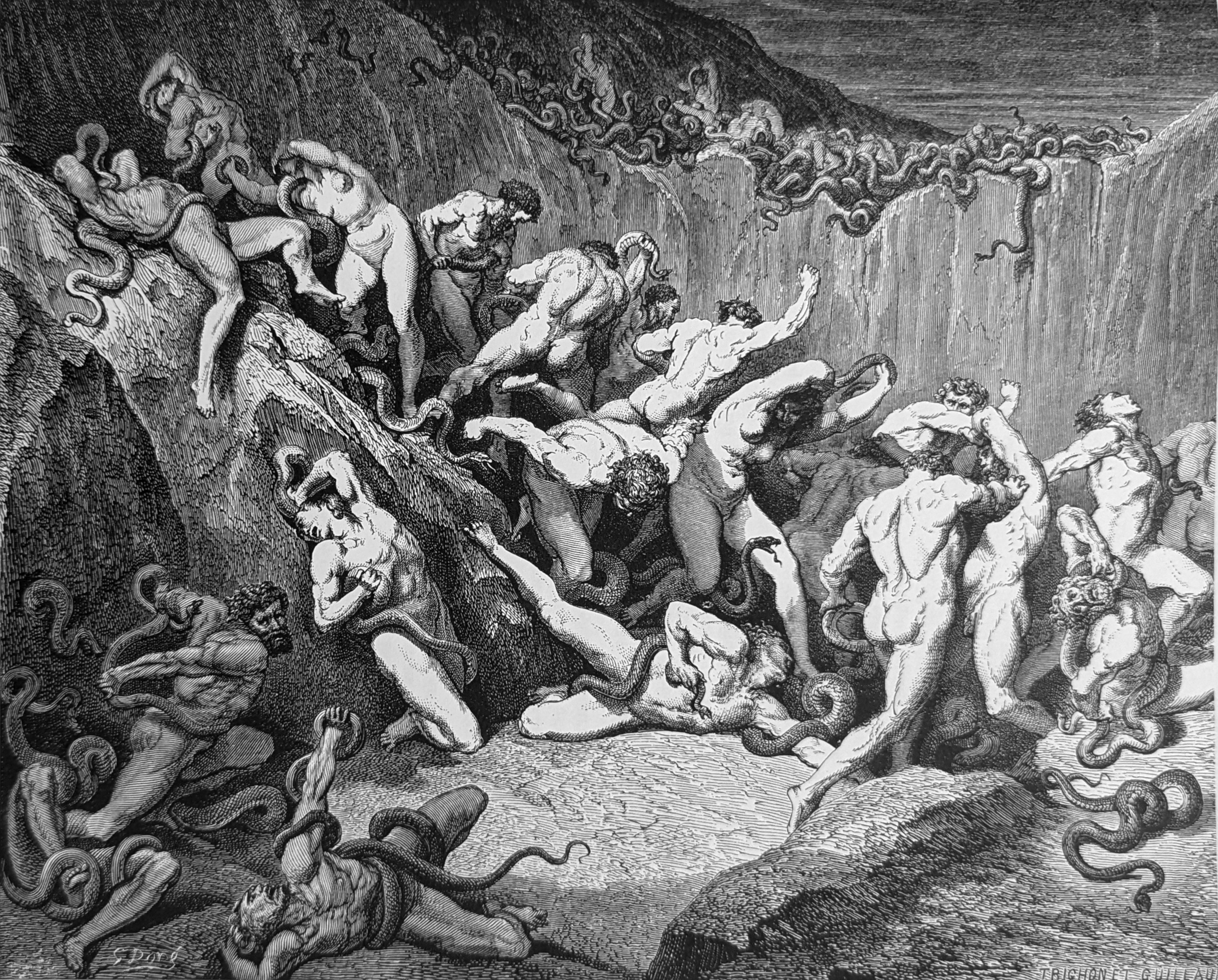

Illustration

Among this cruel and most dismal throng / People were running naked and affrighted. Inf. XXIV, lines 91-92

Footnotes

1. Aquarius, Greek,Ὑδροχόος, Roman, Hydrokhóos, "water-bearer", is the eleventh astrological sign in the zodiac, originating from the constellation Aquarius. Aquarius happens when the Sun passes between January 20 and Februaimport

Aquarius is associated with Ganymede, a handsome Trojan prince in Greek mythology who was abducted by Zeus, transformed into an eagle, and taken to Mount Olympus to serve as the cupbearer to the gods. This connection symbolizes the qualities of the Aquarius zodiac sign, such as creativity and humanitarianism.

2. Dante and Virgil were not down among the serpents and sinners, but were viewing “the whole bolgia” from below the bridge on a terrace of rock, perhaps 10-12 feet above the bottom. His mention of the Libyan desert and it’s specific serpents is directly from Book 9 of Lucan’s epic poem, Pharsalia, on the Roman civil war. Here he mentions only five out of Lucan’s sixteen hideous reptiles! In his commentary on this canto, John Ciardi summarizes thus: “chelydri make their trails smoke and burn, and are amphibious; jaculi fly through the air like darts piercing whatever they hit; phareae plow the ground with their tails; cencri waver from side to side when they move; and amphisbaenae have a head at each end.” Courtney Langdon, in his commentary on this scene remarks that Dante used the Latin names of the serpents to make them “snakier.” To outdo Lucan, though, Dante extends his serpent-filled map to include Ethiopia (which would have included southern Egypt in Dante’s time) and the regions around the Red Sea, which som e commentators say is simply a reference to Egypt, while others go farther east to include all of Arabia that borders that sea. Once again, these sinners are naked, which makes them even more vulnerable. Their terror and shrieking seizes at the reader’s fear, especially when Dante tells us there was no place to hide and no heliotrope-–a semi-precious stone said to be a remedy against snakebite and to make its possessor invisible. Finally, Dante seems to add to the terror by relating that the serpents, much like boas and other huge snakes, coiled themselves around the sinners, wrapping themselves in knots.

3. Dante’s goal in this and the following canto is to raise his poem to the immortal heights of classical mythology that underpins later epic poetry and literature. And so cleverly borrowing from Ovid’s Metamorphosis (Bk. 15), he points to the phoenix as “pro of.” Ovid’s story of the phoenix is one of many. In his version the phoenix simply dies and regenerates at the end of 500 years; it doesn’t burn up. And back to snakes, he’s borrowing again from Book 9 of Lucan’s Pharsalia, where the Roman poet describes i n horrific detail how one soldier burns to death after a snakebite, and another melts away.

4. Amomum, a spice from the family Zingiberaceae, including cardamom.

Myrrh, a red-brown resinous material, the dried sap of a tree of the species Commiphora myrrha, used as perfume, incense or medicine.

5. Vanni Fucci was the bastard son of Fuccio de Lazari, a nobleman of Pistoia, 20 miles northwest of Florence. His reputation is worse, if that’s possible, than his own description of himself. Commentators throughout the last seven centuries almost unanimously condemn him as a fundamentally rotten human being. And Dante, of course, has no good memories of him. In the Italian, he calls him a man of blood and anger. For this Dante may have been surprised to meet him in this part of Hell rather than in Canto 12 immersed in the river of boiling blood. It seems that he had been banished from Pistoia (on more than one occasion), and during the time of Carnival in 1293 he returned. One night during the revelries, he and two companions broke into the Cathedral of San Zeno and stole all the precious objects that were kept in the treasury there. The loot was kept in the house of one of the thieves, Fucci having left the city after committing the crime and laying the blame on an innocent man. Shortly before this unfortunate man was to be hanged, Fucci let it be known whose house the stolen items were in. The man was arrested and hanged; the innocent man was freed. Apparently, Fucci’s role in this crime was not clear until after he died in 1300.

6. Saint Philip Neri CO, born Filippo Romolo Neri (1515–1595) was an Italian Catholic priest who founded the Congregation of the Oratory, a society of secular clergy dedicated to pastoral care and charitable work.

7. Mars is the god of war and also an agricultural guardian. He is the son of Jupiter and Juno, and was pre-eminent among the Roman army's military gods. Most of his festivals were held in March, the month named for him, and in October, the months which traditionally began and ended the season for both military campaigning and farming.

The lightning bolt shot by Mars is generally understood to be a reference to Moroello Malaspina, leader of the Black Guelf army of Florence, but there is uncertainty as to what Fucci is referring to here because there was no battle (“a great storm”) at Pice no near Pistoia – though there were other battles in the region between the feuding parties. Malaspina lived in the river valley of the Magra river (thus Val di Magra or Valdimagra) in the region of Lunigiana between Pisa and Genoa. Interestingly enough, in 1306 Dante was a guest of Malaspina, and though they were earlier members of opposing Guelf factions, their lasting friendship was secured by a close friend of Dante’s. Dante pays homage to the Malaspina family in Canto 8 of the Purgatorio. It is said by the famous Boccaccio that Dante dedicated the Purgatorio to him.

Top of page