Dante's Divine Comedy: Inferno

Canto IV

Virgil shows Dante the mournful shadows of virtuous non-Christians like himself who haunt Limbo, Hell's First Circle, and suffer the spiritual torment of forever seeking God in vain, Virgil speaks about Christ's descent into Hell and his salvation of several Old Testament patriarchs. A glowing light reveals four other great pagan figures—Homer, Horace, Ovid and Lucan. The pilgrim perceives a splendid castle of light in the distance, where the most renowned non-Christian philosophers, poets and warriors dwell.

Broke the deep lethargy within my head

A heavy thunder, so that I upstarted,

Like to a person who by force is wakened;[1]

And round about I moved my rested eyes,

Uprisen erect, and steadfastly I gazed,

To recognize the place wherein I was.

True is it, that upon the verge I found me

Of the abysmal valley dolorous,

That gathers thunder of infinite ululations.

Obscure, profound it was, and nebulous,

So that by fixing on its depths my sight

Nothing whatever I discerned therein.

"Let us descend now into the blind world,"

Began the Poet, pallid utterly;

"I will be first, and thou shalt second be."

And I, who of his color was aware,

Said: "How shall I come, if thou art afraid,

Who'rt wont to be a comfort to my fears?"

And he to me: "The anguish of the people

Who are below here in my face depicts

That pity which for terror thou hast taken.

Let us go on, for the long way impels us."

Thus he went in, and thus he made me enter

The foremost circle that surrounds the abyss.

There, as it seemed to me from listening,

Were lamentations none, but only sighs,

That tremble made the everlasting air.

And this arose from sorrow without torment,

Which the crowds had, that many were and great,

Of infants and of women and of men.

To me the Master good: "Thou dost not ask

What spirits these, which thou beholdest, are?

Now will I have thee know, ere thou go farther,

That they sinned not; and if they merit had,

'Tis not enough, because they had not baptism

Which is the portal of the Faith thou holdest;

And if they were before Christianity,

In the right manner they adored not God;

And among such as these am I myself.

For such defects, and not for other guilt,

Lost are we and are only so far punished,

That without hope we live on in desire."

Great grief seized on my heart when this I heard,

Because some people of much worthiness

I knew, who in that Limbo were suspended.[2]

"Tell me, my Master, tell me, thou my Lord,"

Began I, with desire of being certain

Of that Faith which o'ercometh every error,

"Came any one by his own merit hence,

Or by another's, who was blessed thereafter?"

And he, who understood my covert speech,

Replied: "I was a novice in this state,

When I saw hither come a Mighty One,

With sign of victory incoronate.

Hence he drew forth the shade of the First Parent,

And that of his son Abel, and of Noah,

Of Moses the lawgiver, and the obedient[3]

Abraham, patriarch, and David, king,

Israel with his father and his children,

And Rachel, for whose sake he did so much,

And others many, and he made them blessed;

And thou must know, that earlier than these

Never were any human spirits saved."

We ceased not to advance because he spake,

But still were passing onward through the forest,

The forest, say I, of thick-crowded ghosts.

Not very far as yet our way had gone

This side the summit, when I saw a fire

That overcame a hemisphere of darkness.

We were a little distant from it still,

But not so far that I in part discerned not

That honorable people held that place.

"O thou who honorest every art and science,

Who may these be, which such great honor have,

That from the fashion of the rest it parts them?"

And he to me: "The honorable name,

That sounds of them above there in thy life,

Wins grace in Heaven, that so advances them."

In the mean time a voice was heard by me:

"All honor be to the pre-eminent Poet;

His shade returns again, that was departed."

After the voice had ceased and quiet was,

Four mighty shades I saw approaching us;

Semblance had they nor sorrowful nor glad.

To say to me began my gracious Master:

"Him with that falchion {sword} in his hand behold,

Who comes before the three, even as their lord.

That one is Homer, Poet sovereign;

He who comes next is Horace, the satirist;

The third is Ovid, and the last is Lucan.[4]

Because to each of these with me applies

The name that solitary voice proclaimed,

They do me honor, and in that do well."

Thus I beheld assemble the fair school

Of that lord of the song pre-eminent,

Who o'er the others like an eagle soars.

When they together had discoursed somewhat,

They turned to me with signs of salutation,

And on beholding this, my Master smiled;

And more of honor still, much more, they did me,

In that they made me one of their own band;

So that the sixth was I, 'mid so much wit.

Thus we went on as far as to the light,

Things saying 'tis becoming to keep silent,

As was the saying of them where I was.

We came unto a noble castle's foot,

Seven times encompassed with lofty walls,

Defended round by a fair rivulet;[5]

This we passed over even as firm ground;

Through portals seven I entered with these Sages;

We came into a meadow of fresh verdure.

People were there with solemn eyes and slow,

Of great authority in their countenance;

They spake but seldom, and with gentle voices.

Thus we withdrew ourselves upon one side

Into an opening luminous and lofty,

So that they all of them were visible.

There opposite, upon the green enamel,

Were pointed out to me the mighty spirits,

Whom to have seen I feel myself exalted.

I saw Electra with companions many,

'Mongst whom I knew both Hector and Aeneas,

Caesar in armor with gerfalcon eyes;[6]

I saw Camilla and Penthesilea

On the other side, and saw the King Latinus,

Who with Lavinia his daughter sat;[7]

I saw that Brutus who drove Tarquin forth,

Lucretia, Julia, Marcia, and Cornelia,

And saw alone, apart, the Saladin.[8]

When I had lifted up my brows a little,

The Master I beheld of those who know,

Sit with his philosophic family.

All gaze upon him, and all do him honor.

There I beheld both Socrates and Plato,

Who nearer him before the others stand;

Democritus, who puts the world on chance,

Diogenes, Anaxagoras, and Thales,

Zeno, Empedocles, and Heraclitus;[9]

Of qualities I saw the good collector,

Hight Dioscorides; and Orpheus saw I,

Tully and Livy, and moral Seneca,[10]

Euclid, geometrician, and Ptolemy,

Galen, Hippocrates, and Avicenna,

Averroes, who the great Comment made.

I cannot all of them portray in full,

Because so drives me onward the long theme,

That many times the word comes short of fact.

The sixfold company in two divides;

Another way my sapient Guide conducts me

Forth from the quiet to the air that trembles;

And to a place I come where nothing shines.

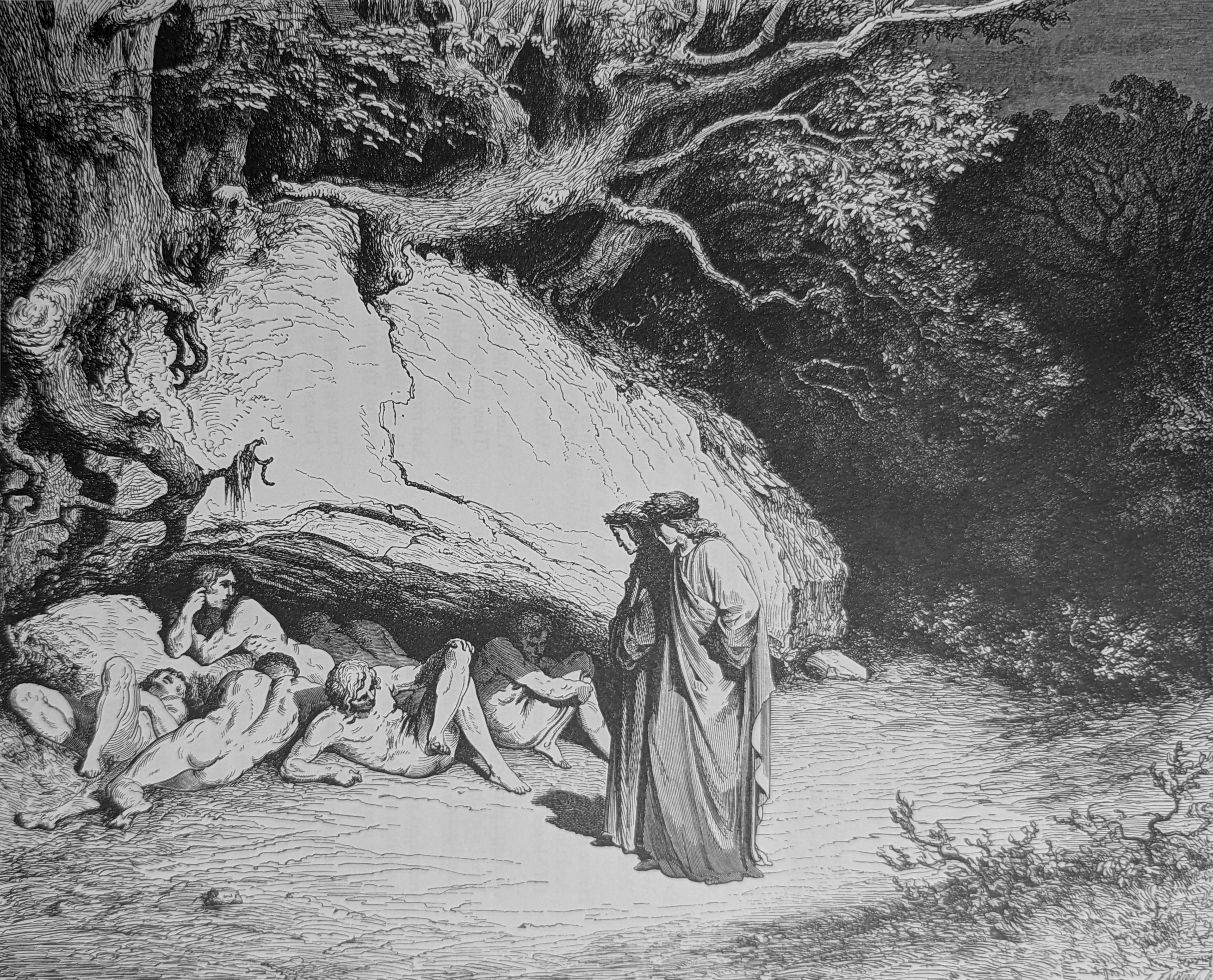

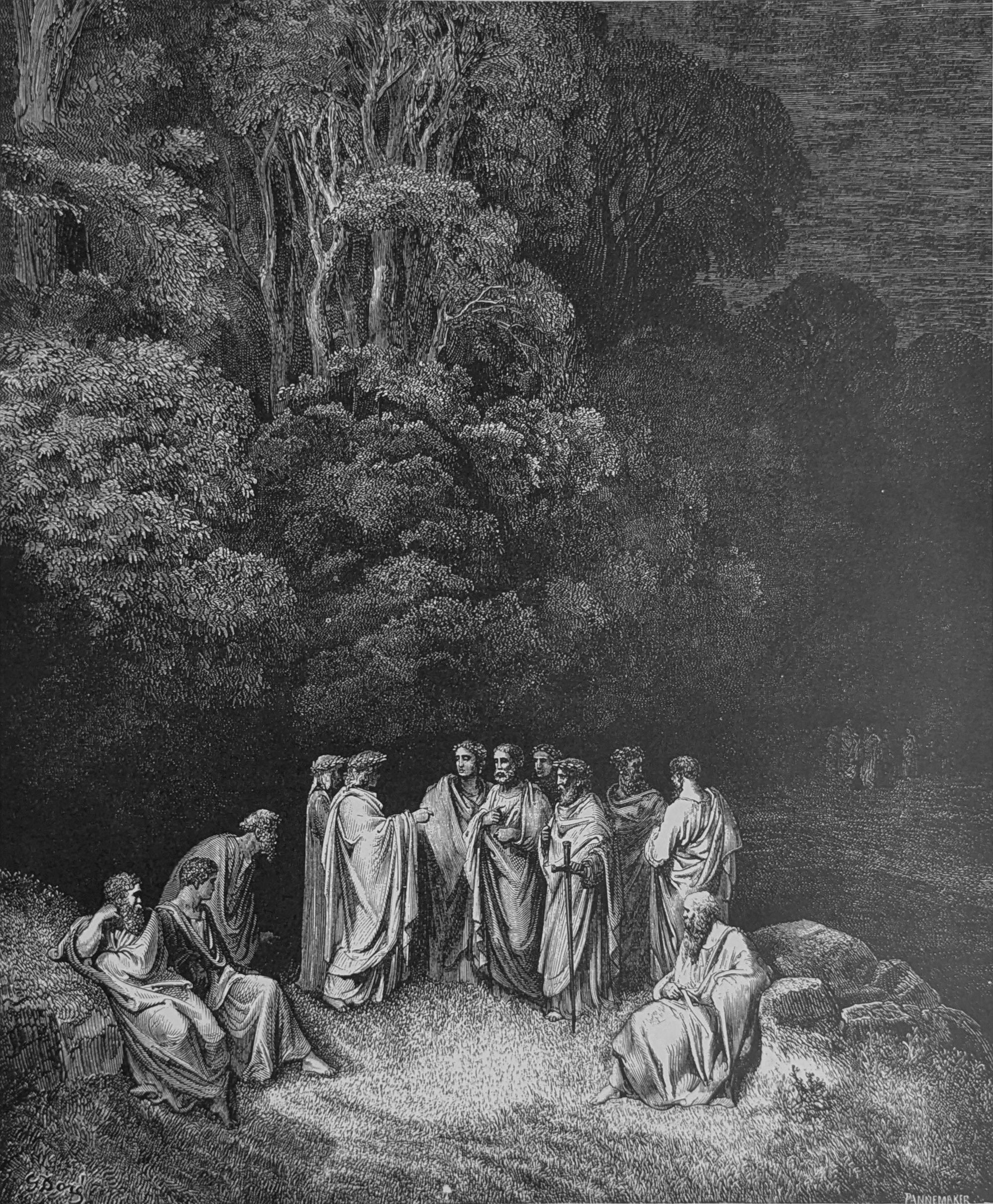

Illustrations

Lost are we and are only so far punished, / That without hope we live on in desire." Inf. IV, lines 41-42

Thus I beheld assemble the fair school / Of that lord of the song pre-eminent, / Who o'er the others like an eagle soars. Inf. IV, lines 94-96

Footnotes

1. Dante had fainted at the earthquake, thunder, lightning, and violent wind that brought Canto 3 to a close. How he and Virgil crossed the Acheron we are not told, but he slowly comes to his senses on the other shore, for he can still hear the thunder booming in the distance and the cries and shrieks of those who are damned.

2. We have entered the first circle of Hell proper, which is Limbo. As the word implies in Latin, it is on the verge or edge of Hell. The souls here do not suffer like everyone else in Hell because they are morally blameless, but by an accident of fate, they have been cut off from the salvation that may well have brought them to a different place. Virgil will explain this shortly. At the time Dante wrote this poem, it was understood from Church teaching (it was never a dogma) that unless a person was baptized they could not be saved. However, this changed in 2007 when, after several years of study, the Church published a document, called “The Hope of Salvation for Infants Who Die Without Being Baptized.” In it, the Church fundamentally states that there is every reason to believe that infants who die without baptism are saved by the loving mercy of God. While the main focus of these teachings was/is on infants, it is clear that Dante broadened the concept of Limbo to include adults as well, and as we shall see.

3. Adam is our (humanity’s) first parent.

4. A reference, of course, to Homer’s grand epics, The Iliad and The Odyssey, which Dante never read because he didn’t read Greek, and there were no translations of these works available to him in his lifetime. What he knew of Homer was by fame and reputation, and from citations of his work in later Latin texts which Dante had access to.

Horace is Quintus Horatius Flaccus, 65-8 BC; Ovid is Publius Ovidius Naso, 43-19 BC, most famous for his Metamorphoses, which seems to have been a major source of mythology for Dante; Lucan is Marcus Annaeus Lucanus, 39-65 AD.

5. As for as the castle and its seven walls, there are several allegorical interpretations for them. The castle might represent wisdom or philosophy. The seven walks lend themselves to a mixture of virtue and learning, but mostly to the classical liberal arts: the trivium (grammar, logic, and rhetoric), and the quadrivium (arithmetic, music, geometry, and astronomy). The flowing stream is often identified with eloquence, which our most eloquent poets would have floated across with ease. Finally, because the lovely meadow is fresh and green, it may represent the lasting fame of the six poets who arrive there. There is certainly also an echo throughout this pleasant walk of the scene in the Aeneid (6:637ff) when Aeneas reaches the Elysian Fields: “Aeneas gained the entrance, sprinkled fresh water over his body, and set up the branch on the threshold before him. Having at last achieved this, the goddess’s task fulfilled, they came to the pleasant places, the delightful grassy turf of the Fortunate Groves, and the homes of the blessed. Here freer air and radiant light clothe the plain, and these have their own sun, and their own stars. Some exercise their bodies in a grassy gymnasium, compete in sports and wrestle on the yellow sand: others tread out the steps of a dance, and sing songs.”

6. Dante’s Electra is the daughter of Atlas and the mother of Dardanus, who founded the city of Troy. She is not to be confused with Electra, the daughter of Agamemnon and sister of Orestes in the great Greek tragedies of Euripides and Sophocles, etc.

Notice how Dante identifies the Trojans first since they, through the hero Aeneas, were the progenitors of the Empire which, here, includes Julius Caesar. As will be seen in various places in his poem, Dante believed in two great kingdoms: the empire of Rome, governed by its rulers, and the kingdom of Heaven, governed on earth by the popes. As he will make clear, so much of the world’s trouble at his time was due to the interference of the empire in the affairs of the Church and vice-versa. Dante believed that the rightful governance of the world belonged to the empire and that the Church had lost its bearings when its leaders forgot their sacred role as Shepherds and prostituted themselves with the gaudy trappings of empire.

7. Latinus ruled the central coastal region of Italy where Aeneas would eventually settle, and from there would begin the eventual empire of Rome. Latinus gave Lavinia to Aeneas in marriage.

8. Saladin might appear as an unusual and out-of-place neighbor to all these Greeks and Romans. But he was famous not only for his prowess as a Muslim warrior, but for his wisdom, and even more so for his compassion and generosity. Having smashed several Crusader strongholds in Palestine on the one hand, he was greatly admired for his humane treatment of his Christian prisoners on the other.

9. Democritus (ca. 460-370 BC): a contemporary of Socrates, who thought that the world exists by chance. Diogenes (ca. 412-323 BC): a Cynic philosopher who taught that the path to virtue was through abstinence and self-control. Thales (ca. 635-545 BC): early Greek philosopher who proposed that the basic element of all things is water. Anaxagoras (500-428 BC): believed that all material things contain a spiritual element that gives them life and form. Empedocles (494-434 BC): fifth century BC; believed that earth, air, fire, and water - empowered by love - gave shape to the cosmos. Zeno (ca. 336-264 BC): founded the Stoic school of philosophy; a follower of Parmenides. Heraclitus (ca. 535-475 BC): believed that fire was the primary form of all matter and that our knowledge is based on sense perception.

10. Dioscorides (ca. 40-90 AD): Greek physician and natural scientist; the first to classify the medicinal properties benefits herbs and plants. Orpheus: the Greek mythical poet and musician who could tame almost anything with his music. Note how Dante purposefully places both Orpheus and Linus—mythic figures among the real Who’s Who of his list. Tully (106-43 BC): another name for the famed Roman orator, Cicero. Linus: a mythical Greek poet and musician. Seneca (4 BC - 65 AD): the noted Stoic philosopher. Euclid (3rd - 4th century BC): the father of geometry. Ptolemy (ca. 100-170 AD): famous in astronomy, mathematics, and geography. It is his geocentric model of the universe that generally accepted until it was replaced by the heliocentric model of Copernicus during the Renaissance (followed later by Kepler and Galileo). Dante uses Ptolemy’s geocentric plan to shape the cosmos he uses throughout the Comedy. Hippocrates (ca. 460-377 BC): founder of medicine as a healing science. Galen (ca. 130-200 BC): famed in the medical arts like Hippocrates. Avicenna (980-1037) and Averroes (1126-1198): two Arabian physicians and philosophers, the latter famous for his commentary on Aristotle.

Top of page