Dante's Divine Comedy: Inferno

Canto XXIII

The sinner's skirmish with the devils reminds Dante of the frog, mouse and hawk fable, where each animal successively deceives the other. Sensing danger, Virgil grabs Dante and they run to the edge of the ravine and slide down into the sixth bolgia. Looking up, they see the devils and are thankful for their escape. The weeping Hypocrites approach in single file, wearing gilded but heavy, lead-lined cloaks. The worst hypocrite of all, Caiaphas, Pontius Pilate's evil counselor, stands crucified and impaled by three stakes. Virgil is angry to discover that Malacoda lied about the bridge in Canto XXI—they will have to climb up a rock-slide instead.

Silent, alone, and without company

We went, the one in front, the other after,

As go the Minor Friars along their way.

Upon the fable of Aesop was directed

My thought, by reason of the present quarrel,

Where he has spoken of the frog and mouse;[1]

For 'mo' and 'issa' are not more alike

Than this one is to that, if well we couple

End and beginning with a steadfast mind.

And even as one thought from another springs,

So afterward from that was born another,

Which the first fear within me double made.

Thus did I ponder: "These on our account

Are laughed to scorn, with injury and scoff

So great, that much I think it must annoy them.

If anger be engrafted on ill-will,

They will come after us more merciless

Than dog upon the leveret which he seizes,"[2]

I felt my hair stand all on end already

With terror, and stood backwardly intent,

When said I: "Master, if thou hidest not

Thyself and me forthwith, of Malebranche

I am in dread; we have them now behind us;

I so imagine them, I already feel them."

And he: "If I were made of leaded glass,

Thine outward image I should not attract

Sooner to me than I imprint the inner.

Just now thy thoughts came in among my own,

With similar attitude and similar face,

So that of both one counsel sole I made.

If peradventure the right bank so slope

That we to the next _Bolgia_ can descend,

We shall escape from the imagined chase."

Not yet he finished rendering such opinion,

When I beheld them come with outstretched wings,

Not far remote, with will to seize upon us.

My Leader on a sudden seized me up,

Even as a mother who noise is wakened,

And close beside her sees the enkindled flames,

Who takes her son, and flies, and does not stop,

Having more care of him than of herself,

So that she clothes her only with a shift;

And downward from the top of the hard bank

Supine he gave him to the pendent rock,

That one side of the other _Bolgia_ walls.

Ne'er ran so swiftly water through a sluice

To turn the wheel of any land-built mill,

When nearest to the paddles it approaches,

As did my Master down along that border,

Bearing me with him on his breast away,

As his own son, and not as a companion.

Hardly the bed of the ravine below

His feet had reached, ere they had reached the hill

Right over us; but he was not afraid;

For the high Providence, which had ordained

To place them ministers of the fifth moat,

The power of thence departing took from all.

A painted people there below we found,

Who went about with footsteps very slow,

Weeping and in their semblance tired and vanquished.

They had on mantles with the hoods low down

Before their eyes, and fashioned of the cut

That in Cologne they for the monks are made.[3]

Without, they gilded are so that it dazzles;

But inwardly all leaden and so heavy

That Frederick used to put them on of straw.

O everlastingly fatiguing mantle!

Again we turned us, still to the left hand

Along with them, intent on their sad plaint;

But owing to the weight, that weary folk

Came on so tardily, that we were new

In company at each motion of the haunch.

Whence I unto my Leader: "See thou find

Some one who may by deed or name be known,

And thus in going move thine eye about."

And one, who understood the Tuscan speech,

Cried to us from behind: "Stay ye your feet,

Ye, who so run athwart the dusky air!

Perhaps thou'lt have from me what thou demandest."

Whereat the Leader turned him, and said: "Wait,

And then according to his pace proceed."

I stopped, and two beheld I show great haste

Of spirit, in their faces, to be with me;

But the burden and the narrow way delayed them.

When they came up, long with an eye askance

They scanned me without uttering a word.

Then to each other turned, and said together:

"He by the action of his throat seems living;

And if they dead are, by what privilege

Go they uncovered by the heavy stole?"

Then said to me: "Tuscan, who to the college

Of miserable hypocrites art come,

Do not disdain to tell us who thou art."

And I to them: "Born was I, and grew up

In the great town on the fair river of Arno,

And with the body am I've always had.

But who are ye, in whom there trickles down

Along your cheeks such grief as I behold?

And what pain is upon you, that so sparkles?"

And one replied to me: "These orange cloaks

Are made of lead so heavy, that the weights

Cause in this way their balances to creak.

Frati Gaudenti were we, and Bolognese;

I Catalano, and he Loderingo

Named, and together taken by thy city,[4]

As the wont is to take one man alone,

For maintenance of its peace; and we were such

That still it is apparent round Gardingo."

"O Friars," began I, "your iniquitous..."

But said no more; for to mine eyes there rushed

One crucified with three stakes on the ground.[5]

When me he saw, he writhed himself all over,

Blowing into his beard with suspirations;

And the Friar Catalan, who noticed this,

Said to me: "This transfixed one, whom thou seest,

Counseled the Pharisees that it was meet

To put one man to torture for the people.

Crosswise and naked is he on the path,

As thou perceivest; and he needs must feel,

Whoever passes, first how much he weighs;

And in like mode his father-in-law is punished

Within this moat, and the others of the council,

Which for the Jews was a malignant seed."[6]

And thereupon I saw Virgilius marvel

O'er him who was extended on the cross

So vilely in eternal banishment.

Then he directed to the Friar this voice:

"Be not displeased, if granted thee, to tell us

If to the right hand any pass slope down

By which we two may issue forth from here,

Without constraining some of the black angels

To come and extricate us from this deep."

Then he made answer: "Nearer than thou hopest

There is a rock, that forth from the great circle

Proceeds, and crosses all the cruel valleys,

Save that at this 'tis broken, and does not bridge it;

You will be able to mount up the ruin,

That sidelong slopes and at the bottom rises."

The Leader stood awhile with head bowed down;

Then said: "The business badly he recounted

Who grapples with his hook the sinners yonder."

And the Friar: "Many of the Devil's vices

Once heard I at Bologna, and among them,

That he's a liar and the father of lies."

Thereat my Leader with great strides went on,

Somewhat disturbed with anger in his looks;

Whence from the heavy-laden I departed

After the prints of his beloved feet.

Illustrations

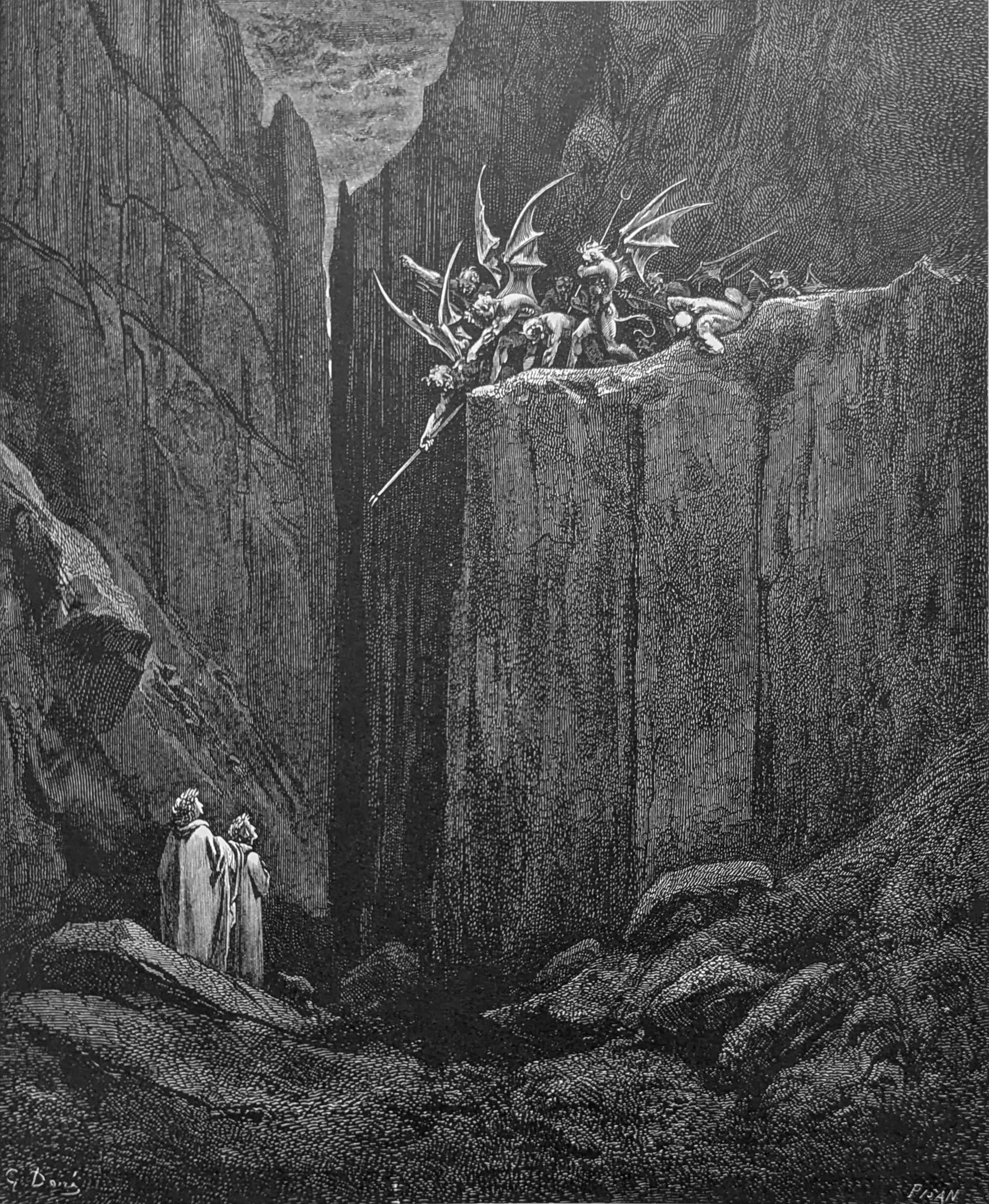

Hardly the bed of the ravine below / His feet had reached, ere they had reached the hill / Right over us; Inf. XXIII, lines 52-54

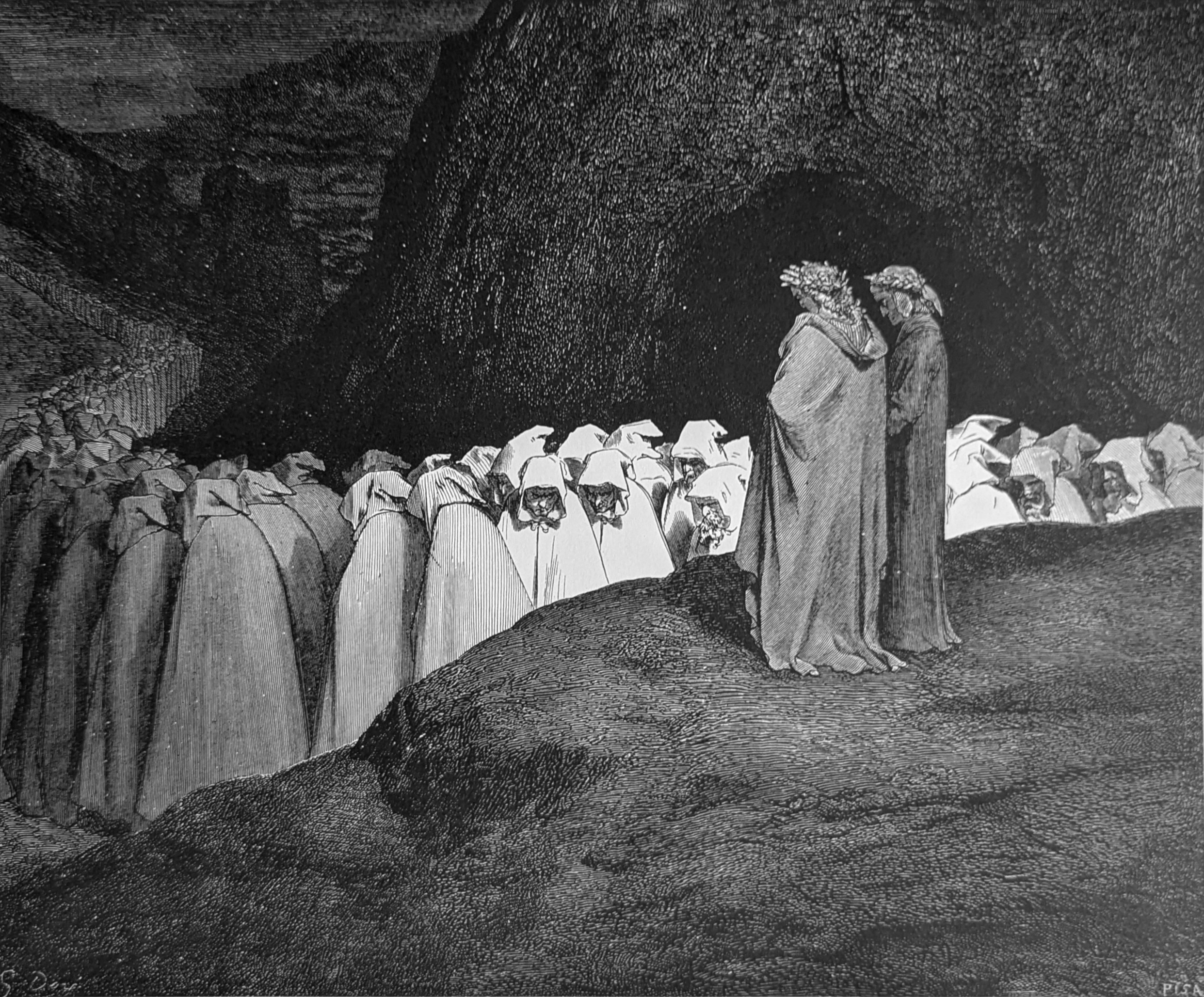

They had on mantles with the hoods low down / Before their eyes, Inf. XXIII, lines 61-62

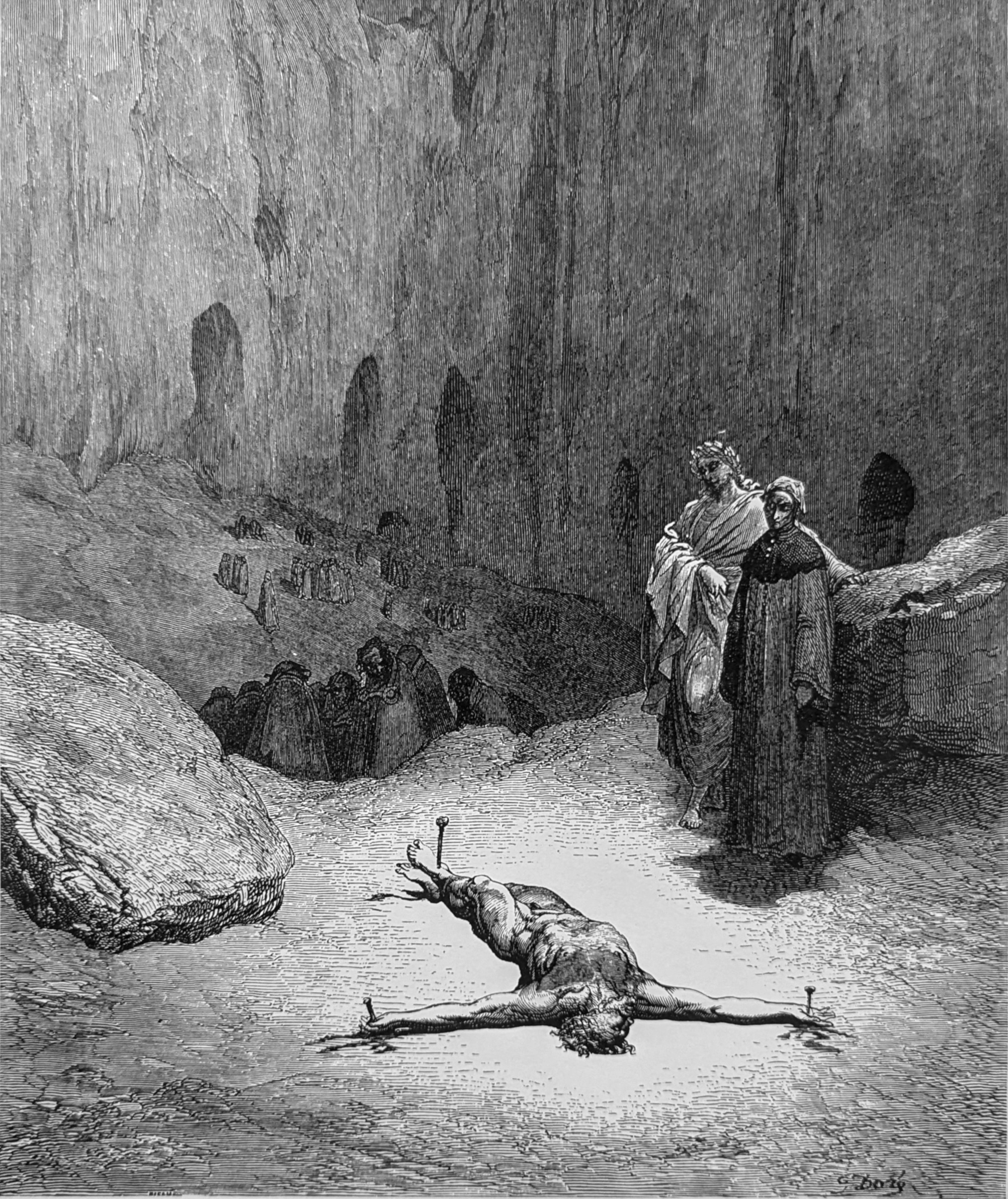

"This transfixed one, whom thou seest, / Counselled the Pharisees that it was meet / To put one man to torture for the people. Inf. XXIII, lines 115-117

Footnotes

1. The fable of the mouse and the frog was probably not written by Aesop, but it was, nevertheless, popular in the Middle Ages and it offers the reader another way to consider the comedy of the last two cantos. A mouse needs to cross a stream and a frog offers him a ride. But the mouse fears that he’ll fall off and drown. So, the frog ties the mouse to one of his legs and begins to swim away—with the wicked intention of diving down and drowning the mouse! This said, the mouse is desperately trying to stay afloa t when a hawk spies it from aloft, swoops down, pulls both the mouse and the frog up out of the water, and devours them both! Dante doesn’t give us the whole fable, but what he notes is enough to make us think about that story and its moral. In a similar way, “there” and “at that place” point in the same direction, but in different ways. Some commentators liken the mouse and the frog to Calcabrina and Alichino. Others see both Dante and Virgil as the “mice” deceived by the devilish “frogs” who, most likely, would have been happy to drown the two travelers in the boiling tar. But, like the frog, their evil came back upon them and their victims escaped unscathed.

2. Middle English, leveret(te), Old French leveret, lievre, “hare”, Latin, leporem, of obscure origin.

3. That Dante mentions the famous monastery of Cluny probably has to do with stories that circulated in Medieval times about pretentious monks or wealthy monasteries. He is not shy about pointing out excesses in the Church. Most commentators agree that Dante’s Clugnì is a reference to Cluny, but there are some who think he may have been referring to another great monastery,—at Cologne,—about which there is a story appropriate to this canto. It was said that the monks at Cologne, because of the fame and dignity of their monastery, appealed to the pope that they be allowed to wear scarlet robes girded by silver belts. His answer was an order that they wear coarse gray instead. Even St. Bernard criticized excesses in monastic dress. As for Frederick’s torture-capes , Dante is referring to another story (not verified by hard evidence) that Frederick II executed traitors by wrapping them in sheets of lead and placing them in heated cauldrons until the lead melted. One could imagine a different,—and far worse,—contrapasso of wearing red hot capes instead of lead ones. Finally, the fact that Dante always holds the Church and its leaders (including members of religious orders) to a higher standard is subtly evident in the comparison between the monk-like gowns of the hypocrites and the straw-like “gowns” used by Frederick.

4. The Jovial Friars (Frati Gaudenti) was the popular name for a religious order of laymen known as the Knights of Saint Mary, founded in Bologna in 1261. One might call it a kind of spiritual militia because their papal charter allowed them to bear arms in defense of the Church. But their chief mission in Dante’s time was to negotiate reconciliations between warring factions whose civil strife disrupted the good government of cities. Both Catalano (a Guelf) and Loderingo (a Ghibelline) were among the founders o f this “order,” and they were sent to Florence in 1266 by Pope Clement IV ostensibly to settle disputes between the Guelfs and Ghibellines. But his goal was to control Florence by ravaging the Ghibelline party. Unfortunately, these two knights compromised their objectivity—not to mention their virtue—and aroused the ire of the populace. Favoritism of the Guelf faction led to the destruction of the homes of prominent Ghibelline leaders in the Gardingo section of Florence (in the neighborhood of the present Palazzo Vecchio) as Catalano explains. Because members of this order were not bound by strict vows they could live outside the monastery, they could marry and have children, and they accepted and enjoyed many other social privileges. Not all members were disreputable, but those that were gave it a reputation for laxity and involvement in various scandals—thus its nickname, “Jovial,”—and it was suppressed by Pope Sixtus V in 1558. After long careers as roving mayors/governors, both men retired to and eventually died at the order’s monastery in Bologna.

5. After hearing from Catalano and Loderingo, and realizing who they were and the suffering they caused, Dante was ready to rebuke them. But they must have been walking along slowly, Dante listening as he looked ahead, because just as he started his rebuke he caught sight of a different sinner in front of them who was actually crucified onto the ground! Mid sentence, Dante appears to be so taken aback at the sight that Catalano answers his implied question and almost excitedly tells him all he needs to know. Among the contrapassi that Dante creates, this is one of the most clever and brilliantly executed. In the Christian world, and certainly in Dante’s time, Caiaphas, the Jewish High Priest who condemned Jesus, is a shrewd villain worse than poor Judas. Without naming him, Catalano simply refers to the verse in St. John’s Gospel where Caiaphas actually condemns himself.

6. Catalano isn’t finished, and here is the brilliant contrapasso. As we know, the bottom of this particular bolgia is rather narrow. Caiaphas is nailed across the road, and the heavily-leaded hypocrites do not walk around him and all his colleagues. No, they literally trample over him and the rest, letting them feel the weight of all the hypocrisy in Hell. Cleverly, as the Gospel speaks of Jesus being “lifted up” on his cross, Caiaphas is nailed to the ground in Hell. Furthermore, he and his fellow-hypocrites a re set apart from the rest of the sinners in this ditch—a first in Dante’s Hell. Not only are they all crucified to the ground, but they are also naked. Recall that the hypocrites are the only sinners in hell who are clothed. But it would be insufficient that these particular hypocrites simply wear a lead gown like the rest. Instead, they personally feel the weight of every other lead gown in this place.

Top of page