Dante's Divine Comedy: Inferno

Canto XXV

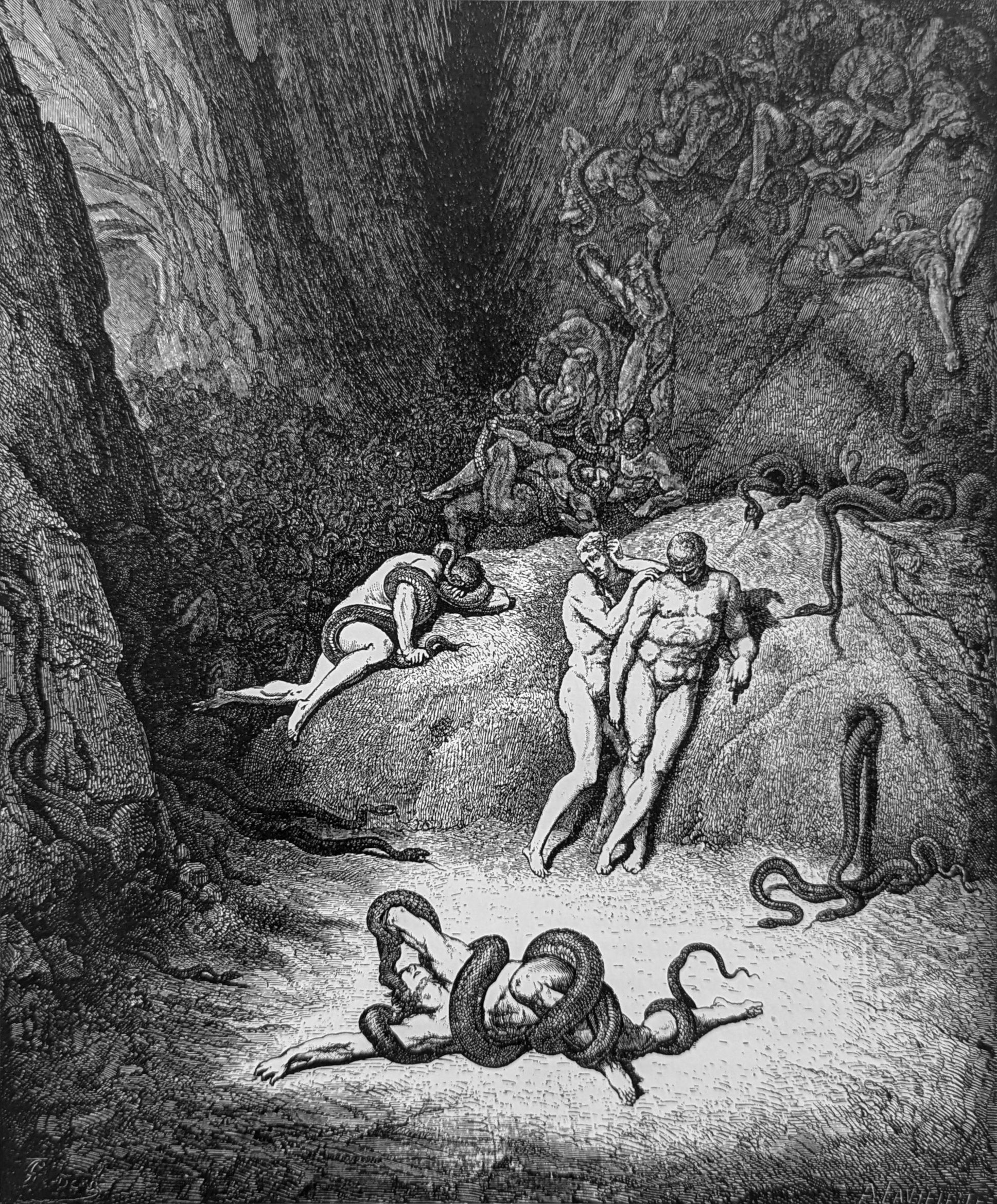

Vanni Fucci, the militant leader from Pistoia, makes an obscene gesture towards God with his fist before being immobilized by a bevy of snakes who wrap themselves around him. When he breaks free, Cacus the Centaur gallops off in pursuit, with a fire-belching dragon on his shoulders. Three shadows appear. They are looking for Cianfa, who appears as a man-become-snake. He attacks Agnello, with whom he merges into one monstrous being. Another shadow exchanges his serpentine form with Buoso. Only Puccio Sciancato retains his shape.

At the conclusion of his words, the thief

Lifted his hands aloft with both the figs,

Crying: "Take that, God, for at thee I aim them."

From that time forth the serpents were my friends;

For one entwined itself about his neck

As if it said: "I will not thou speak more;"

And round his arms another, and rebound him,

Clinching itself together so in front,

That with them he could not a motion make.

Pistoia, ah, Pistoia! why resolve not

To burn thyself to ashes and so perish,

Since in ill-doing thou thy seed excellest?

Through all the somber circles of this Hell,

Spirit I saw not against God so proud,

Not he who fell at Thebes down from the walls!

He fled away, and spake no further word;

And I beheld a Centaur full of rage

Come crying out: "Where is, where is the scoffer?"

I do not think Maremma has so many

Serpents as he had all along his back,

As far as where our countenance begins.[1]

Upon the shoulders, just behind the nape,

With wings wide open was a dragon lying,

And he sets fire to all that he encounters.

My Master said: "That one is Cacus, who

Beneath the rock upon Mount Aventine

Created oftentimes a lake of blood.[2]

He goes not on the same road with his brothers,

By reason of the fraudulent theft he made

Of the great herd, which he had near to him;

Whereat his tortuous actions ceased beneath

The mace of Hercules, who peradventure

Gave him a hundred, and he felt not ten."[3]

While he was speaking thus, he had passed by,

And spirits three had underneath us come,

Of which nor I aware was, nor my Leader,

Until what time they shouted: "Who are you?"

On which account our story made a halt,

And then we were intent on them alone.

I did not know them; but it came to pass,

As it is wont to happen by some chance,

That one to name the other was compelled,

Exclaiming: "Where can Cianfa have remained?"

Whence I, so that the Leader might attend,

Upward from chin to nose my finger laid.[4]

If thou art, Reader, slow now to believe

What I shall say, it will no marvel be,

For I who saw it hardly can admit it.

As I was holding raised on them my brows,

Behold! a serpent with six feet darts forth

In front of one, and fastens wholly on him.

With middle feet it bound him round the paunch,

And with the forward ones his arms it seized;

Then thrust its teeth through one cheek and the other;

The hindermost it stretched upon his thighs,

And put its tail through in between the two,

And up behind along the reins outspread it.

Ivy was never fastened by its barbs

Unto a tree so, as this horrible reptile

Upon the other's limbs entwined its own.

Then they stuck close, as if of heated wax

They had been made, and intermixed their color;

Nor one nor other seemed now what he was;

E'en as proceedeth on before the flame

Upward along the paper a brown color,

Which is not black as yet, and the white dies.

The other two looked on, and each of them

Cried out: "O me, Agnello, how thou changest!

Behold, thou now art neither two nor one."

Already the two heads had one become,

When there appeared to us two figures mingled

Into one face, wherein the two were lost.

Of the four lists were fashioned the two arms,

The thighs and legs, the belly and the chest

Members became that never yet were seen.

Every original aspect there was canceled;

Two and yet none did the perverted image

Appear, and such departed with slow pace.

Even as a lizard, under the great scourge

Of days canicular, exchanging hedge,

Lightning appeareth if the road it cross;

Thus did appear, coming towards the bellies

Of the two others, a small fiery serpent,

Livid and black as is a peppercorn.

And in that part whereat is first received

Our aliment, it one of them transfixed;

Then downward fell in front of him extended.

The one transfixed looked at it, but said naught;

Nay, rather with feet motionless he yawned,

Just as if sleep or fever had assailed him.

He at the serpent gazed, and it at him;

One through the wound, the other through the mouth

Smoked violently, and the smoke commingled.

Henceforth be silent Lucan, where he mentions

Wretched Sabellus and Nassidius,

And wait to hear what now shall be shot forth.[5]

Be silent Ovid, of Cadmus and Arethusa,

For if him to a snake, her to fountain,

Converts he fabling, that I grudge him not,

Because two natures never front to front

Has he transmuted, so that both the forms

To interchange their matter ready were.

Together they responded in such wise,

That to a fork the serpent cleft his tail,

And eke the wounded drew his feet together.

The legs together with the thighs themselves

Adhered so, that in little time the juncture

No sign whatever made that was apparent.

He with the cloven tail assumed the figure

The other one was losing, and his skin

Became elastic, and the other's hard.

I saw the arms draw inward at the armpits,

And both feet of the reptile, that were short,

Lengthen as much as those contracted were.

Thereafter the hind feet, together twisted,

Became the member that a man conceals,

And of his own the wretch had two created.

While both of them the exhalation veils

With a new color, and engenders hair

On one of them and depilates the other,

The one uprose and down the other fell,

Though turning not away their impious lamps,

Underneath which each one his muzzle changed.

He who was standing drew it tow'rds the temples,

And from excess of matter, which came thither,

Issued the ears from out the hollow cheeks;

What did not backward run and was retained

Of that excess made to the face a nose,

And the lips thickened far as was befitting.

He who lay prostrate thrusts his muzzle forward,

And backward draws the ears into his head,

In the same manner as the snail its horns;

And so the tongue, which was entire and apt

For speech before, is cleft, and the bi-forked

In the other closes up, and the smoke ceases.

The soul, which to a reptile had been changed,

Along the valley hissing takes to flight,

And after him the other speaking sputters.

Then did he turn upon him his new shoulders,

And said to the other: "I'll have Buoso run,

Crawling as I have done, along this road."[6]

In this way I beheld the seventh ballast

Shift and re-shift, and here be my excuse

The novelty, if aught my pen transgress.

And notwithstanding that mine eyes might be

Somewhat bewildered, and my mind dismayed,

They could not flee away so secretly

But that I plainly saw Puccio Sciancato,

And he it was who sole of three companions,

Which came in the beginning, was not changed;

The other was he whom thou, Gaville, weepest.

Illustration

"O me, Agnello, how thou changest! / Behold, thou now art neither two nor one." Inf. XXV, lines 68-69

Footnotes

1. The Maremma was a wild, malarial, swampy area along the coast of Tuscany, uninhabited by humans because it was filled with snakes. Here it’s another of Dante’s recollections from real life. The draining and reclamation of the Maremma region was begun by Ferdinando I de’ Medici, and today it is a lush agricultural region virtually the opposite of what it was before the 14th century.

2. First, we recall that Dante and Virgil were standing safely on a kind of outcropping between the bridgehead above them and the floor of this bolgia below. And because they were busy with Vanni Fucci and the arrival of Cacus, they didn’t realize they were being watched by three new thieves, whose naming of one of their now-lost companions gives them away.

3. Hercules is the Roman equivalent of the Greek divine hero Heracles, son of Jupiter and the mortal Alcmena. In classical mythology, Hercules is famous for his strength and for his numerous far-ranging adventures.

Cacus is a centaur and he is a thief. Why is Cacus here? Virgil gives us the major part of the answer as found in his Aeneid. However, it is Dante who makes Cacus a centaur, perhaps because Virgil writes that he is half-human. In the mythological stories, Cacus was the son of Vulcan, a giant, who lived in a cave in Mount Aventine in Rome, who breathed fire and feasted on human flesh. In the Aeneid, he stole the cattle of Hercules who beat him to death soon afterward. As for the manner of Cacus’ death, Dante borrows (“steals?”) from Ovid; and while Ovid’s Hercules delivers only four blows, Dante greatly exaggerates here with a hundred! If one recalls that Dante has several mythological creatures guarding various areas of Hell, Cacus fits well here among the thieves. And his “badge,” as it were, is the swarm of snakes he carries on his back and the great fire-spitting dragon on his shoulders. As Musa notes in his commentary, Cacus plays a double role here: “He is both a punished thief and a punishing guardian of t he thieves.”

4. Little else is known about these thieves (we will encounter five of them) except that they were all Florentine. While their family names are given here, Dante himself does not reveal them. They’ve been stolen. The thieves are Agnello dei Brunelleschi, Buoso degli Abati, Puccio dei Galigai (same as Puccio Scianciato), Cianfa dei Donati, and Francesco Guercio dei Cavalcanti. Their asking where their companion Cianfa has gone will be answered now in an unbelievable scene.

5. Virgil. Now, though, emerging from behind the smoke, as it were, he doesn’t address us as readers. No. He addresses his resources directly as a kind of braggart, telling them that he’s going to go beyond them and invent something new. Previously, Dante has taken pride in his Florentine heritage by being noted here and there as a Florentine. And he’s made sure that individuals have recognized the elegance of his speech (an advertisement for this poem). Here, though he’s more elegant, Dante basically tells Lucan and Ovid to “give it up” or “shut up” about their stories of soldiers who were bitten by snakes and either melted or blew up (Nasidius and Sabellus), or of mythological figures turned to snakes and fountains (Cadmus and Arethusa). And note carefully what he’s telling them, as though he’s their teacher critiquing their work: “This is ok. But look, you haven’t gone far enough with this. You simply transform people into other forms. I’m going to transform them into each other—perfectly! When he says this, he speaks specifically of the transformation of both “form” and “substance.” One might be tempted to pass over this statement but Dante uses both terms on purpose to signify a “complete and total” transformation of both soul (form) and body (substance), not just one or the other. And where is he “stealing” these distinctions from? Classical philosophy (Aristotle) and theology (St. Thomas Aquinas).

6. It is Francesco dei Cavalcanti (the serpent now become a man) who speaks these vengeful words to Puccio Sciancato, the only thief left untransformed, about Buoso, the man now become a serpent. And gracefully stepping down from the literary heights he has just spoken from, Dante asks his readers to excuse him if we feel he has been either excessive or unclear in his descriptions. Still amplifying the reality of what he has presented to us, he cleverly claims that it was hard for him to believe what he saw because he, too, was stunned by it. Each thief was a countryman of Florence. And to make matters even more believable-–right to the end-–he names the last sinner, not by name, but by what he did, tricking us, as it were, to agree with him by looking up Gaville and piecing together that this final unnamed thief is Francesco dei Cavalcanti. All of the confused identity is precisely what Dante has wanted to achieve by his metamorphoses. Francesco was murdered in Gaville, a small town 25 miles southeast of Florence. To avenge his death, the Cavalcanti family killed a great many of its citizens.

Top of page