Dante's Divine Comedy: Inferno

Canto VIII

Dante realizes that the fires on top of the tower are a signal to the city of Dis. Phlegyas quickly appears and the two poets are ferried across the Styx. An. angry shadow, Philippo Argenti {a politician and a citizen of Florence}, rises up from the mire and tries to attack the boat. Repelled by Virgil, he is then viciously attacked by the other souls. The poets disembark at the gate of Dis. They are denied access by the demonic angels within. Virgil goes alone to speak with them, to no avail. The poets must wait for help from Heaven.

I say, continuing, that long before

We to the foot of that high tower had come,

Our eyes went upward to the summit of it,

By reason of two flamelets we saw placed there,

And from afar another answer them,

So far, that hardly could the eye attain it.

And, to the sea of all discernment turned,

I said: "What sayeth this, and what respondeth

That other fire? and who are they that made it?"

And he to me: "Across the turbid waves

What is expected thou canst now discern,

If reek of the morass conceal it not."

Cord never shot an arrow from itself

That sped away athwart the air so swift,

As I beheld a very little boat

Come o'er the water tow'rds us at that moment,

Under the guidance of a single pilot,

Who shouted, "Now art thou arrived, fell soul?"

"Phlegyas, Phlegyas, thou criest out in vain

For this once," said my Lord; "thou shalt not have us

Longer than in the passing of the slough."[1]

As he who listens to some great deceit

That has been done to him, and then resents it,

Such became Phlegyas, in his gathered wrath.

My Guide descended down into the boat,

And then he made me enter after him,

And only when I entered seemed it laden.

Soon as the Guide and I were in the boat,

The antique prow goes on its way, dividing

More of the water than 'tis wont with others.

While we were running through the dead canal,

Uprose in front of me one full of mire,

And said, "Who'rt thou that comest ere the hour?"

And I to him: "Although I come, I stay not;

But who art thou that hast become so squalid?"

"Thou seest that I am one who weeps," he answered.

And I to him: "With weeping and with wailing,

Thou spirit maledict, do thou remain;

For thee I know, though thou art all defiled."

Then stretched he both his hands unto the boat;

Whereat my wary Master thrust him back,

Saying, "Away there with the other dogs!"

Thereafter with his arms he clasped my neck;

He kissed my face, and said: "Disdainful soul,

Blessed be she who bore thee in her bosom.

That was an arrogant person in the world;

Goodness is none, that decks his memory;

So likewise here his shade is furious.

How many are esteemed great kings up there,

Who here shall be like unto swine in mire,

Leaving behind them horrible dispraises!"

And I: "My Master, much should I be pleased,

If I could see him soused into this broth,

Before we issue forth out of the lake."

And he to me: "Ere unto thee the shore

Reveal itself, thou shalt be satisfied;

Such a desire 'tis meet thou shouldst enjoy."

A little after that, I saw such havoc

Made of him by the people of the mire,

That still I praise and thank my God for it.

They all were shouting, "At Philippo Argenti!"

And that exasperate spirit Florentine

Turned round upon himself with his own teeth.[2]

We left him there, and more of him I tell not;

But on mine ears there smote a lamentation,

Whence forward I intent unbar mine eyes.

And the good Master said: "Even now, my Son,

The city draweth near whose name is Dis,

With the grave citizens, with the great throng."

And I: "Its mosques already, Master, clearly

Within there in the valley I discern

Vermilion, as if issuing from the fire[3]

They were." And he to me: "The fire eternal

That kindles them within makes them look red,

As thou beholdest in this nether Hell."

Then we arrived within the moats profound,

That circumvallate that disconsolate city;

The walls appeared to me to be of iron.

Not without making first a circuit wide,

We came unto a place where loud the pilot

Cried out to us, "Debark, here is the entrance."

More than a thousand at the gates I saw

Out of the Heavens rained down, who angrily

Were saying, "Who is this that without death[4]

Goes through the kingdom of the people dead?"

And my sagacious Master made a sign

Of wishing secretly to speak with them.

A little then they quelled their great disdain,

And said: "Come thou alone, and he begone

Who has so boldly entered these dominions.

Let him return alone by his mad road;

Try, if he can; for thou shalt here remain,

Who hast escorted him through such dark regions."

Think, Reader, if I was discomforted

At utterance of the accursed words;

For never to return here I believed.

"O my dear Guide, who more than seven times

Hast rendered me security, and drawn me

From imminent peril that before me stood,

Do not desert me," said I, "thus undone;

And if the going farther be denied us,

Let us retrace our steps together swiftly."

And that Lord, who had led me thitherward,

Said unto me: "Fear not; because our passage

None can take from us, it by Such is given.

But here await me, and thy weary spirit

Comfort and nourish with a better hope;

For in this nether world I will not leave thee."

So onward goes and there abandons me

My Father sweet, and I remain in doubt,

For No and Yes within my head contend.

I could not hear what he proposed to them;

But with them there he did not linger long,

Ere each within in rivalry ran back.

They closed the portals, those our adversaries,

On my Lord's breast, who had remained without

And turned to me with footsteps far between.

His eyes cast down, his forehead shorn had he

Of all its boldness, and he said, with sighs,

"Who has denied to me the dolesome houses?"

And unto me: "Thou, because I am angry,

Fear not, for I will conquer in the trial,

Whatever for defense within be planned.

This arrogance of theirs is nothing new;

For once they used it at less secret gate,

Which finds itself without a fastening still.

O'er it didst thou behold the dead inscription;

And now this side of it descends the steep,

Passing across the circles without escort,

One by whose means the city shall be opened."

Illustrations

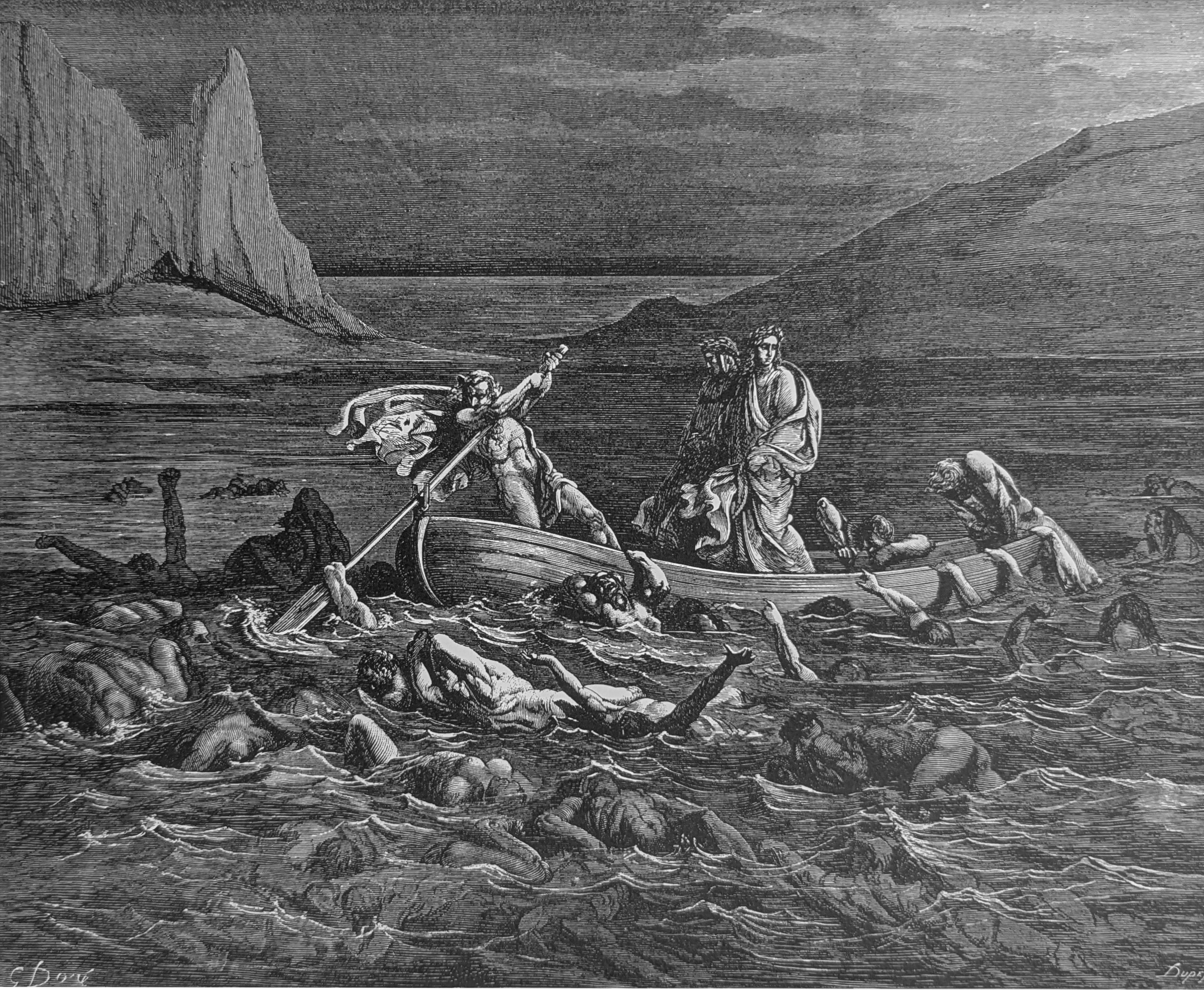

The antique prow goes on its way, dividing / More of the water than 'tis wont with others. Inf. VIII, lines 29-30

Then stretched he both his hands unto the boat; / Whereat my wary Master thrust him back, Inf. VIII, lines 40-41

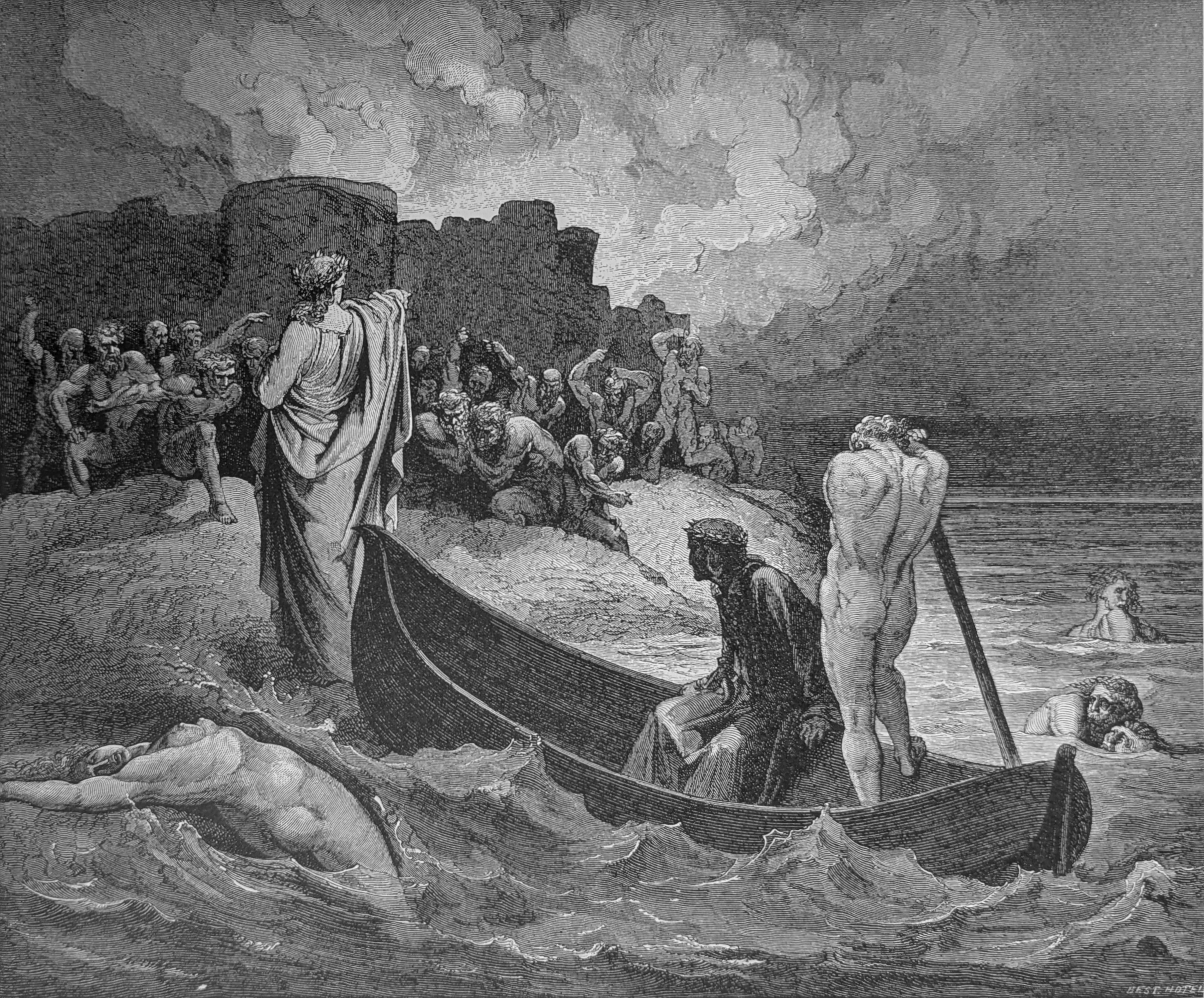

I could not hear what he proposed to them; / But with them there he did not linger long, / Ere each within in rivalry ran back. Inf. VIII, lines 112-114

Footnotes

1. Recall when Dante and Virgil approached the Acheron in Canto 3. Charon shouted at Dante and Virgil challenged him back. Here, the scene repeats itself, this time with Phlegyas. Once again, Dante brings a character from classical mythology to take a role in his Inferno. Phlegyas, whose name means “fiery” or “fiery one,” was the son of Mars. When his daughter, Coronis, was violated by Apollo, Phlegyas, gone mad with revenge, set fire to the Temple of Apollo in Delphi. The god killed Phlegyas for his sacrilege and condemned him to Tartarus, a place of torture deep in the Underworld. Dante makes good use of him as guardian of the Styx (which means “hateful”) and its wrathful inhabitants and as a link to a wrathful encounter about to come.

2. As we will discover soon enough, this is the soul of Filippo Argenti. Dante must have recognized him as soon as he saw him, but he never identifies him by name. What’s significant here, however, is the dialogue. Why Filippo would ask who Dante was and then say that he’s actually here early is somewhat of a mystery. Except that it was most likely meant as an insult, as were Dante’s heated replies. Filippo was of the Cavicciuli-Adimari family, Black Guelfs who were bitterly opposed to Dante. It is said that “Argenti” (silver) was a nickname because Filippo was so rich and so proud that he even shod his horse in silver. He was a big man, loud, and prone to extreme fits of anger at the least provocation. His hatred of Dante is obvious when he tells him that he’s “early.” Seeing Dante, his political enemy, in the boat while he’s mired in the fetid swamp must have increased the anger he was already condemned for. Dante never identifies himself, and perhaps as a nasty response to one of his enemies, he rouses the proud sinner’s wrath even more by asking who he is, covered with slime. With that, Filippo seems to have met his match, and now identifies himself as “one who weeps.” This may be a sad admission for such a proud man; more likely it’s an arrogant taunt this proud man throws back at Dante, knowing that the trouble he caused Dante in life would certainly have made him weep. Of course, in earlier cantos, an admission like this on the sinner’s part brought pity and sympathy from Dante. But not here. Is Dante starting to “grow up” in the face of terrible sin rather than having another emotional cave-in? Dante adds his own condemnation of Filippo with not an ounce of pity, and without naming him, tells the sinner he knows exactly who he is under his mask of mud. In life, Argenti’s wrathful arrogance left no room for pity, and here in Hell he gets none! While one might be tempted to think less of Dante for his part in this petty fight, looked at differently Dante’s behavior is probably better understood as righteous anger, not so much at the sinner as the sin – but even here, Dante has a ways to go. In Canto 6 Ciacco told Dante that Florence was being ruined by pride, envy, and greed. Here we might well add anger, and later we can add violence. Dante has seen how his city was torn apart by this sin, and when he sees one of the perpetrators, he lets go. But, we’re getting ahead of ourselves here. The fight is not over yet.

3. The word minarets (in some translations mosques), unmistakably evokes the religion of Islam which, in Dante’s time was considered as a heretical sect. In Dante’s conception here, these heretical places of worship, counter to Christian churches, are red hot and they give the city of Dis a lurid glow from the distance. Just as images of cities from afar show their spires and towers, so this city of the damned shows first the evidence of its wicked cults. Filled with heretics, this is a place of blasphemy and disbelief. As a matter of fact, once inside the City, Dante will discover countless fiery tombs filled with heretics. Contrary to popular conceptions, and phrases like “the fires of Hell,” Dante’s Hell has fire in a few appropriate places, but not everywhere.

4. Put together, the various descriptions of this place remind the reader of a great medieval fortress, complete with its walls, its towers, and its moat. If we follow Dante’s directions here, they have left the marshy Styx and have been sailing for a while in a moat paralleling the walls of Dis until they come to the city’s gate. There Phlegyas rudely sends Virgil and Dante scurrying off the boat.

Top of page