Dante's Divine Comedy: Inferno

Canto XXXIII

The poets witness the gruesome spectacle of the Ghibelline Count Ugolino della Gherardesca gnawing at the skull of his former collaborator, Archbishop Ruggieri. He stops in the middle of his gory repast to tell the story of his incarceration and murder along with that of his innocent children. The travelers venture into Ptolomea, the third division of Lake Cocytus, where dwell those who betrayed guests and associates. Any tears shed here freeze and lock the eyes in a fixed stare. Friar Alberigo agrees to talk if the icy layer is removed. He declares his soul and that of another to be dead but their bodies to be 'alive' on Earth and possessed by demons. Dante breaks his promise.

His mouth uplifted from his grim repast,

That sinner, wiping it upon the hair

Of the same head that he behind had wasted.

Then he began: "Thou wilt that I renew

The desperate grief, which wrings my heart already

To think of only, ere I speak of it;

But if my words be seed that may bear fruit

Of infamy to the traitor whom I gnaw,

Speaking and weeping shalt thou see together.

I know not who thou art, nor by what mode

Thou hast come down here; but a Florentine

Thou seemest to me truly, when I hear thee.

Thou hast to know I was Count Ugolino,

And this one was Ruggieri the Archbishop;

Now I will tell thee why I am such a neighbor.[1]

That, by effect of his malicious thoughts,

Trusting in him I was made prisoner,

And after put to death, I need not say;

But ne'ertheless what thou canst not have heard,

That is to say, how cruel was my death,

Hear shalt thou, and shalt know if he has wronged me.

A narrow perforation in the mew,

Which bears because of me the title of Famine,

And in which others still must be locked up,

Had shown me through its opening many moons

Already, when I dreamed the evil dream

Which of the future rent for me the veil.

This one appeared to me as lord and master,

Hunting the wolf and whelps upon the mountain

For which the Pisans cannot Lucca see.[2]

With sleuth-hounds gaunt, and eager, and well trained,

Gualandi with Sismondi and Lanfianchi

He had sent out before him to the front.

After brief course seemed unto me forespent

The father and the sons, and with sharp tushes

It seemed to me I saw their flanks ripped open.

When I before the morrow was awake,

Moaning amid their sleep I heard my sons

Who with me were, and asking after bread.

Cruel indeed art thou, if yet thou grieve not,

Thinking of what my heart foreboded me,

And weep'st thou not, what art thou wont to weep at?

They were awake now, and the hour drew nigh

At which our food used to be brought to us,

And through his dream was each one apprehensive;

And I heard locking up the under door

Of the horrible tower; whereat without a word

I gazed into the faces of my sons.

I wept not, I within so turned to stone;

They wept; and darling little Anselm mine

Said: 'Thou dost gaze so, father, what doth ail thee?"

Still not a tear I shed, nor answer made

All of that day, nor yet the night thereafter,

Until another sun rose on the world.

As now a little glimmer made its way

Into the dolorous prison, and I saw

Upon four faces my own very aspect,

Both of my hands in agony I bit;

And, thinking that I did it from desire

Of eating, on a sudden they uprose,

And said they: 'Father, much less pain 'twill give us

If thou do eat of us; thyself didst clothe us

With this poor flesh, and do thou strip it off."

I calmed me then, not to make them more sad.

That day we all were silent, and the next.

Ah! obdurate Earth, wherefore didst thou not open?

When we had come unto the fourth day, Gaddo

Threw himself down outstretched before my feet,

Saying, 'My father, why dost thou not help me?"

And there he died; and, as thou seest me,

I saw the three fall, one by one, between

The fifth day and the sixth; whence I betook me,

Already blind, to groping over each,

And three days called them after they were dead;

Then hunger did what sorrow could not do."

When he had said this, with his eyes distorted,

The wretched skull resumed he with his teeth,

Which, as a dog's, upon the bone were strong.

Ah! Pisa, thou opprobrium of the people

Of the fair land there where the 'Si' doth sound,

Since slow to punish thee thy neighbors are,[3]

Let the Capraia and Gorgona move,

And make a hedge across the mouth of Arno

That every person in thee it may drown!

For if Count Ugolino had the fame

Of having in thy castles thee betrayed,

Thou shouldst not on such cross have put his sons.

Guiltless of any crime, thou modern Thebes!

Their youth made Uguccione and Brigata,

And the other two my song doth name above!

We passed still farther onward, where the ice

Another people ruggedly enswathes,

Not downward turned, but all of them reversed.

Weeping itself there does not let them weep,

And grief that finds a barrier in the eyes

Turns itself inward to increase the anguish;

Because the earliest tears a cluster form,

And, in the manner of a crystal visor,

Fill all the cup beneath the eyebrow full.

And notwithstanding that, as in a callus,

Because of cold all sensibility

Its station had abandoned in my face,

Still it appeared to me I felt some wind;

Whence I: "My Master, who sets this in motion?

Is not below here every vapor quenched?"

Whence he to me: "Full soon shalt thou be where

Thine eye shall answer make to thee of this,

Seeing the cause which raineth down the blast."

And one of the wretches of the frozen crust

Cried out to us: "O souls so merciless

That the last post is given unto you,

Lift from mine eyes the rigid veils, that I

May vent the sorrow which impregns my heart

A little, e'er the weeping recongeal."

Whence I to him: "If thou wouldst have me help thee

Say who thou wast; and if I free thee not,

May I go to the bottom of the ice."

Then he replied: "I am Friar Alberigo;

He am I of the fruit of the bad garden,

Who here a date am getting for my fig."[4]

"O," said I to him, "now art thou, too, dead?"

And he to me: "How may my body fare

Up in the world, no knowledge I possess.

Such an advantage has this Ptolomaea,

That oftentimes the soul descendeth here

Sooner than Atropos in motion sets it.[5]

And, that thou mayest more willingly remove

From off my countenance these glassy tears,

Know that as soon as any soul betrays

As I have done, his body by a demon

Is taken from him, who thereafter rules it,

Until his time has wholly been revolved.

Itself down rushes into such a cistern;

And still perchance above appears the body

Of yonder shade, that winters here behind me.

This thou shouldst know, if thou hast just come down;

It is Ser Branca d' Oria, and many years

Have passed away since he was thus locked up."

"I think," said I to him, "thou dost deceive me;

For Branca d' Oria is not dead as yet,

And eats, and drinks, and sleeps, and puts on clothes."

"In moat above," said he, "of Malebranche,

There where is boiling the tenacious pitch,

As yet had Michel Zanche not arrived,

When this one left a devil in his stead

In his own body and one near of kin,

Who made together with him the betrayal.

But hitherward stretch out thy hand forthwith,

Open mine eyes;"—and open them I did not,

And to be rude to him was courtesy.

Ah, Genoese! ye men at variance

With every virtue, full of every vice

Wherefore are ye not scattered from the world?

For with the vilest spirit of Romagna

I found of you one such, who for his deeds

In soul already in Cocytus bathes,[6]

And still above in body seems alive!

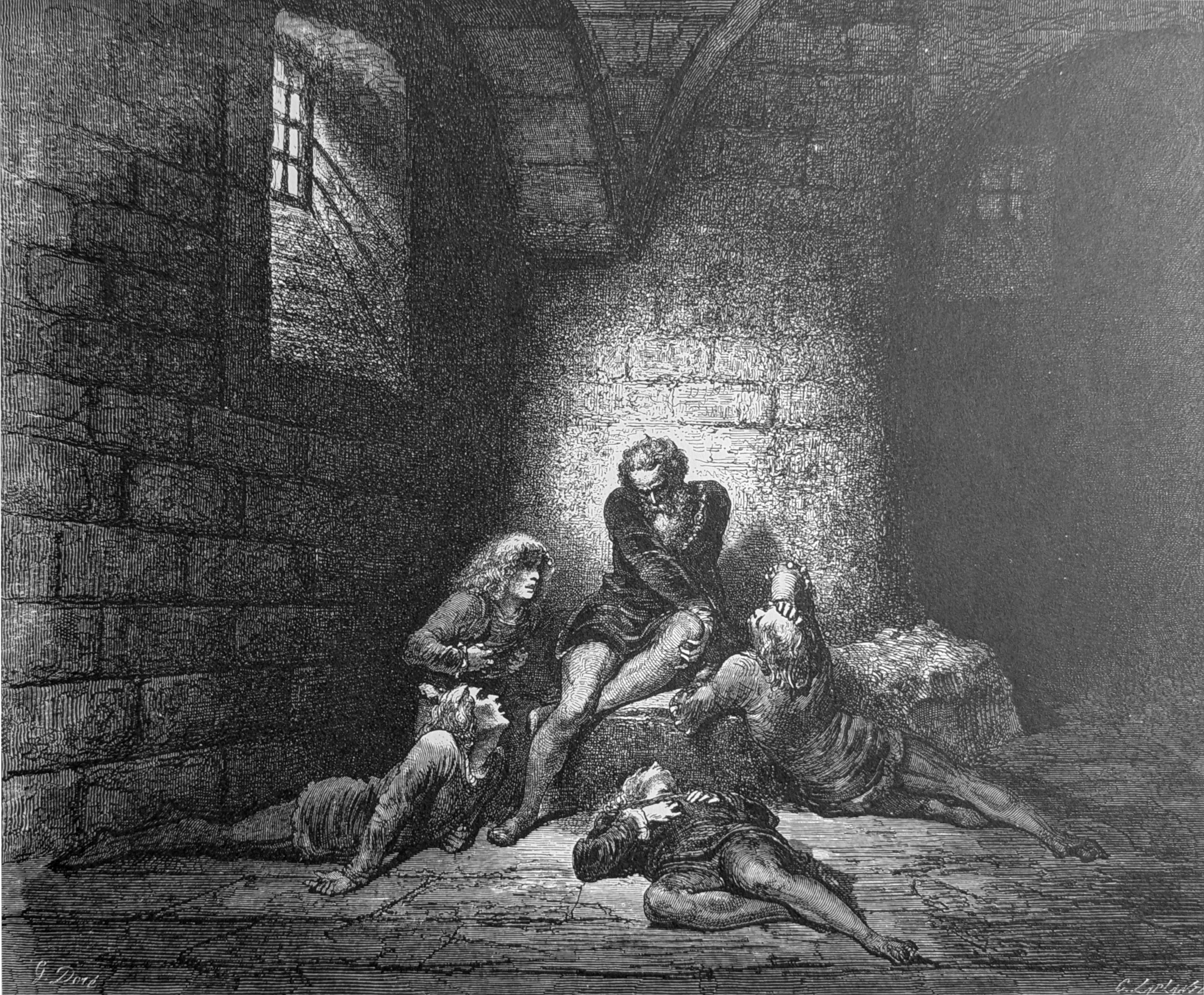

Illustrations

"I calmed me then, not to make them more sad." Inf. XXXIII, line 64

"Gaddo/Threw himself down outstretched before my feet, / Saying, 'My father, why dost thou not help me?"" Inf. XXXIII, lines 67-69

"Then hunger did what sorrow could not do." Inf. XXXIII, line 75

Footnotes

1. On several occasions during his travels in Hell, Dante has heard “confessions” from many of the sinners. While it’s too late for a “sacramental” confession because Ugolino is dead and his deeds are now public, what is about to unfold is, nevertheless, a confession of the deeply personal, virtually secret, “ghastly” side of a very public story. Noting that Dante is Florentine by his dialect, Ugolino knows that he knows the public story and gives him just a few of the largest details to refresh his memory and to heighten anticipation for the “real story” about to unfold. E.H. Plumptre validates Ugolino’s surmise in his commentary:

“Linguistic commentators point to the fact that the speech of Dante in the last seven lines of Canto 32 contain in the original Italian no less than seven words which distinctly belong to the dialect of Florence.”

Furthermore, at the end of the previous canto, Dante asked Ugolino to trust him to tell his story—the secret, private, ghastly part of the story that no one witnessed. By allowing Dante to be the judge in the “case” he is about to present, Ugolino puts his trust in the Poet. In other words, Dante has complete literary license to tell the truth or to fabricate something entirely different. To a certain extent, of course, Ugolino is hoping to win Dante’s sympathy as did Francesca in Canto 5 who, in words not unlike Ugolino’s, told the Poet: “There’s no greater pain than remembering happy times when you’re deep in grief.” In the Italian, both Francesca and Ugolino also refer to their deaths as “offenses” against them as a way to subtly focus their stories on themselves and highlight their innocence. So, who were Ugolino and Ruggieri?

Ugolino della Gherardesca (ca. 1220-1289), the Count of Donoratico (about 40 miles south of Pisa), was a member of a noble Ghibelline family in Guelf-controlled Pisa. From around the time he was 30 years old he played a significant role in the history of Pisa, in and out of the political scene there, and also exiled several times (but returned) for various intrigues involving family, power, and party—not to mention murder. At one point he was appointed as the Podestà of the city. In spite of his family’s Ghibelline tradition, Ugolino was at one time the head of one of the two Guelf factions in the city. His nephew, Nino Visconti, was head of the other faction. (We will meet Nino in Canto 8 of the Purgatorio.) Wanting supreme power for himself, Ugolino apparently conspired with the leader of the Ghibellines, Archbishop Ruggieri (whose brains he here feasts on). Trusting Ruggieri completely, together they successfully drove Nino out of Pisa. But this action weakened the Pisan Guelfs. Seizing upon this opportunity, Ruggieri made the appearance of supporting Ugolino. However, in August 1288 the Archbishop unleashed the pent-up anger of the Ghibellines, and with them orchestrated an attack on Ugolino’s palace joined by the leading Ghibelline families of Pisa, the Lanfranchi, Sismondi, and Gualandi. At that point, Ruggieri betrayed Ugolino, accusing him of treason by engaging in secret negotiations with Pisa’s enemies, Florence and Lucca, and in the process ceding to them certain strategic Pisan castles and strongholds. (Apparently, these transactions were legitimate.) Ugolino was arrested in the uprising along with his two sons and two grandsons. They were ultimately locked in a tower belonging to the Gualandi in the present-day Piazza dei Cavalieri, and the keys were thrown into the Arno River. (The tower is gone, but the building it was attached to, not far from Pisa’s Leaning Tower, is still standing.) In March of 1289 the tower was nailed shut by order of the Archbishop and Ugolino and his sons and grandsons were starved to death. After this, the tower where they died was known as the Torre del fame, Tower of Hunger. One account has it that their bodies were taken out and burned. Another has it that the bodies were wrapped up and hastily buried at the nearby church of the Franciscans. Still another tells us that, seeing its Pisan allies weakened, the Florentine Guelfs, under the leadership of Guido da Montefeltro (see Canto 27), arrived in Pisa at or about the same time Ugolino and the four boys died. He may or may not have known about them and left them to starve nonetheless.

Ruggieri degli Ubaldini (died 1295) was born into a powerful family of Mugello (20 miles NE of Florence). He was the son of Ubaldino della Pila (noted among the gluttons in Purg. 24), brother of Ottaviano (the Younger) Ubaldini, bishop of Bologna, nephew of the influential Ghibelline Cardinal Ottaviano degli Ubaldini of Bologna (most likely “the Cardinal” mentioned by Farinata in Canto 10), and cousin of Ugolino d’Azzo (see Purg. 14). In 1278 he was named Archbishop of Pisa. A staunch Ghibelline, he became the leader of that party and was involved in several of the ups and downs of Count Ugolino’s political career noted above. And, as noted above, he betrayed Ugolino both by pretending to support him and then accusing him of treason which led to his terrible death and that of his sons and grandsons. Following Ugolino’s death, Ruggieri attempted to secure the position of Podestà for himself, but could not overcome the opposition of the Viscontis whom he had earlier connived with Ugolino to banish from Pisa. Following the widespread publication of the manner of Count Ugolino’s death and that of his sons and grandsons, Pope Nicholas IV condemned Ruggieri but he died before the Archbishop could be punished. Other sources note that Ruggieri was stripped of his ecclesiastical office and spent the rest of his life in prison.

2. In the symbolic context of a dream narrative Ugolino now recounts for Dante the circumstances of his arrest. He sees Ruggieri dressed in lordly hunting gear. The dogs are his enemies: members of the Gualandi, Sismondi, and Lanfranchi families (all Ghibellines like Ruggieri). The murderous gang are the Ghibelline populace roused against Ugolino by Ruggieri. They are chasing a wolf (Ugolino) and its cubs (his sons and grandsons) up a mountain between Pisa and Lucca (some think this is the tower where they are imprisoned). This is Monte San Giuliano, a long, flat mountain upon which, according to Plumptre, were several of the fortresses and strongholds Ugolino was accused of ceding to Lucca. He and his “cubs” may well have been heading toward Lucca where he would have had many allies. Then, in keeping with the bestial imagery used in this part of Hell, the wolf and its cubs tire and are overtaken by the vicious dogs.

3. The ghastly “secret” story of Ugolino and the circumstances of his death comes to a close here. Both the now-public story is joined with what was, until now, unknown. But this full revelation elicits a strong apostrophe from Dante the Poet, who uses both his role as a poet and his creation, the Commedia, to condemn the city of Pisa—not for punishing Ugolino—which he deserved, but for killing his innocent children. In the Poet’s estimation, after hearing Ugolino’s story, Pisa now shares an infamous reputation for hideous crimes with ancient Thebes, and it should be wiped off the face of the earth in order not to taint the rest of Italy—where honorable people say “sì.” To this effect, Dante wishes that the mouth of the Arno be blocked by the two islands that lay off the coast of Pisa, thus drowning the city and its wicked inhabitants. He has in mind here another famous curse—this one against Egypt in Lucan’s Pharsalia (VIII:827ff):

“What curse can I invoke upon that ruthless land in reward for so great a crime? May Nile reverse his waters and be stayed in the region where he rises; may the barren fields crave winter rains; and may all the soil break up into the crumbling sands of Ethiopia.”

Recall how he called for the destruction of the city of Pistoia at the beginning of Canto 25 after his encounter with Vanni Fucci, who made the “figs” at God.

4. Alberigo di Ugolino dei Manfredi was a native of Faenza, the Manfredi family being the Guelf lords of that city. Late in his life he also became one of the Jovial Friars, two of whom we met in Canto 23 among the hypocrites, and he was alive in 1300, the year in which Dante sets his Poem. In 1286, Alberigo and his younger brother, Manfredo, got into a violent argument, during which Manfredo struck him in the face. Apologies were made and calm was restored. Later, to celebrate their reconciliation, Alberigo invited Manfredo and his son, Alberghetto, to a banquet honoring the occasion. However, he had not forgotten the injury to his person and to his pride. When, during the meal, Alberigo called for the fruit—the signal—assassins rushed from behind the drapery and murdered his guests there at the table. With a bit of black humor, Alberigo actually jokes with Dante as he identifies himself. In those days, figs were cheap, but dates were costly, so “To get a date for a fig” meant to get more than you bargained for. Deservedly so, the Ottimo Commento reports that Alberigo did the same thing a year earlier! Musa adds: “Alberigo was notorious for his brutal cynicism and treachery, and according to Lana, the expression ‘bring the fruit’ became proverbial as an allusion to treachery and murder.”

5. It seems that all three traitors arrived in Hell at different times. The murderers, Branca D’Oria and his nephew accomplice arrived first, followed by Michel Zanche whom they murdered. Some commentators suggest that this difference in time is due to the fact that their souls may have dropped to Hell the moment they conceived of their heinous crime, not when they actually committed it. So, the murderers are here in Ptolomea along with Friar Alberigo, and Michel Zanche, the murdered man, who was a grafter, was sent to the boiling pitch in the fifth bolgia above.

All of these men, of course, end up in Hell. While one might be inclined to think—and probably rightly so—that the murderers got what they deserved, the murdered man, though he was a mortal sinner and deserving of Hell, might have had a later conversion of heart and sought forgiveness for his crimes if he had lived longer. We will encounter this issue early in the Purgatorio. There are sobering stories from Dante’s time, and later, of murderers who knew that their victims had committed mortal sins and deliberately killed them before they had a chance to confess so that their souls would go to Hell. All of this points to the fragility and tenuous nature of human existence, of sin and forgiveness, of Hell and Heaven—a theme that runs all through both the Inferno and the Purgatorio.

6. Dante’s crossing from Antenora to Ptolomea was marked by a powerful apostrophe against Pisa. His crossing now from Ptolomea to Judecca is marked by another apostrophe—this time against Genoa. And recall, as noted above, his apostrophe against Pistoia at the beginning of Canto 25. As a matter of fact, his outcry that he should find one of Genoa’s great citizens here virtually mirrors his outcry at the beginning of Canto 26 where he expresses his chagrin at finding five notable Florentines among the thieves in Hell. Add to this Dante’s shock in finding one of Genoa’s leading citizens (Branca D’Oria) in company with Romagna’s worst sinner—Friar Alberigo. Why did our mothers warn us about “bad companions?”

Top of page