Dante's Divine Comedy: Inferno

Canto XVIII

As the poets descend on Geryon's back in a slow gyre, Dante describes his bird's-eye view of Hell's Eighth Circle (malebolge). {Fraud} It has ten rocky clefts (bolgias), each one connected to the next by a curved bridge. At the edge of the first bolgia, two lines of naked souls are moving in opposite directions—the Panders walking towards Virgil and Dante and the Seducers filing past alongside them. Dante recognizes Venedico Caccianemico, a Bolognese Guelf leader, and Jason of the Argonauts. The second bolgia is characterized by the foul stench of Flatterers drowning in excrement.

There is a place in Hell called Malebolge,

Wholly of stone and of an iron color,

As is the circle that around it turns.[1]

Right in the middle of the field malign

There yawns a well exceeding wide and deep,

Of which its place the structure will recount.

Round, then, is that enclosure which remains

Between the well and foot of the high, hard bank,

And has distinct in valleys ten its bottom.

As where for the protection of the walls

Many and many moats surround the castles,

The part in which they are a figure forms,

Just such an image those presented there;

And as about such strongholds from their gates

Unto the outer bank are little bridges,

So from the precipice's base did crags

Project, which intersected dikes and moats,

Unto the well that truncates and collects them.

Within this place, down shaken from the back

Of Geryon, we found us; and the Poet

Held to the left, and I moved on behind.

Upon my right hand I beheld new anguish,

New torments, and new wielders of the lash,

Wherewith the foremost Bolgia was replete.

Down at the bottom were the sinners naked;

This side the middle came they facing us,

Beyond it, with us, but with greater steps;

Even as the Romans, for the mighty host,

The year of Jubilee, upon the bridge,

Have chosen a mode to pass the people over;[2]

For all upon one side towards the Castle

Their faces have, and go unto St Peter's;

On the other side they go towards the Mountain.

This side and that, along the livid stone

Beheld I horned demons with great scourges,

Who cruelly were beating them behind.

Ah me! how they did make them lift their legs

At the first blows! and sooth not any one

The second waited for, nor for the third.

While I was going on, mine eyes by one

Encountered were; and straight I said: "Already

With sight of this one I am not unfed."

Therefore I stayed my feet to make him out,

And with me the sweet Guide came to a stand,

And to my going somewhat back assented;

And he, the scourged one, thought to hide himself,

Lowering his face, but little it availed him;

For said I: "Thou that castest down thine eyes,

If false are not the features which thou bearest,

Thou art Venedico Caccianimico;

But what doth bring thee to such pungent sauces?"[3]

And he to me: "Unwillingly I tell it;

But forces me thine utterance distinct,

Which makes me recollect the ancient world.

I was the one who the fair Ghisola

Induced to grant the wishes of the Marquis,

Howe'er the shameless story may be told.[4]

Not the sole Bolognese am I who weeps here;

Nay, rather is this place so full of them,

That not so many tongues to-day are taught

'Twixt Reno and Savena to say 'sipa;'

And if thereof thou wishest pledge or proof,

Bring to thy mind our avaricious heart."

While speaking in this manner, with his scourge

A demon smote him, and said: "Get thee gone

Pander, there are no women here for coin."

I joined myself again unto mine Escort;

Thereafterward with footsteps few we came

To where a crag projected from the bank.

This very easily did we ascend,

And turning to the right along its ridge,

From those eternal circles we departed.

When we were there, where it is hollowed out

Beneath, to give a passage to the scourged,

The Guide said: "Wait, and see that on thee strike

The vision of those others evil-born,

Of whom thou hast not yet beheld the faces,

Because together with us they have gone."

From the old bridge we looked upon the train

Which tow'rds us came upon the other border,

And which the scourges in like manner smite.

And the good Master, without my inquiring,

Said to me: "See that tall one who is coming,

And for his pain seems not to shed a tear;

Still what a royal aspect he retains!

That Jason is, who by his heart and cunning

The Colchians of the Ram made destitute.[5]

He by the isle of Lemnos passed along

After the daring women pitiless

Had unto death devoted all their males.

There with his tokens and with ornate words

Did he deceive Hypsipyle, the maiden

Who first, herself, had all the rest deceived.

There did he leave her pregnant and forlorn;

Such sin unto such punishment condemns him,

And also for Medea is vengeance done.

With him go those who in such wise deceive;

And this sufficient be of the first valley

To know, and those that in its jaws it holds."

We were already where the narrow path

Crosses athwart the second dike, and forms

Of that a buttress for another arch.

Thence we heard people, who are making moan

In the next _Bolgia_, snorting with their muzzles,

And with their palms beating upon themselves

The margins were incrusted with a mold

By exhalation from below, that sticks there,

And with the eyes and nostrils wages war.

The bottom is so deep, no place suffices

To give us sight of it, without ascending

The arch's back, where most the crag impends.

Thither we came, and thence down in the moat

I saw a people smothered in a filth

That out of human privies seemed to flow;

And whilst below there with mine eye I search,

I saw one with his head so foul with ordure,

It was not clear if he were clerk or layman.

He screamed to me: "Wherefore art thou so eager

To look at me more than the other foul ones?"

And I to him: "Because, if I remember,

I have already seen thee with dry hair,

And thou'rt Alessio Interminei of Lucca;

Therefore I eye thee more than all the others."[6]

And he thereon, belaboring his pumpkin:

"The flatteries have submerged me here below,

Wherewith my tongue was never surfeited."

Then said to me the Guide: "See that thou thrust

Thy visage somewhat farther in advance,

That with thine eyes thou well the face attain

Of that uncleanly and disheveled drab,

Who there doth scratch herself with filthy nails,

And crouches now, and now on foot is standing.

Thais the harlot is it, who replied

Unto her paramour, when he said, 'Have I

Great gratitude from thee?'--Nay, marvelous;"[7]

And herewith let our sight be satisfied."

Illustrations

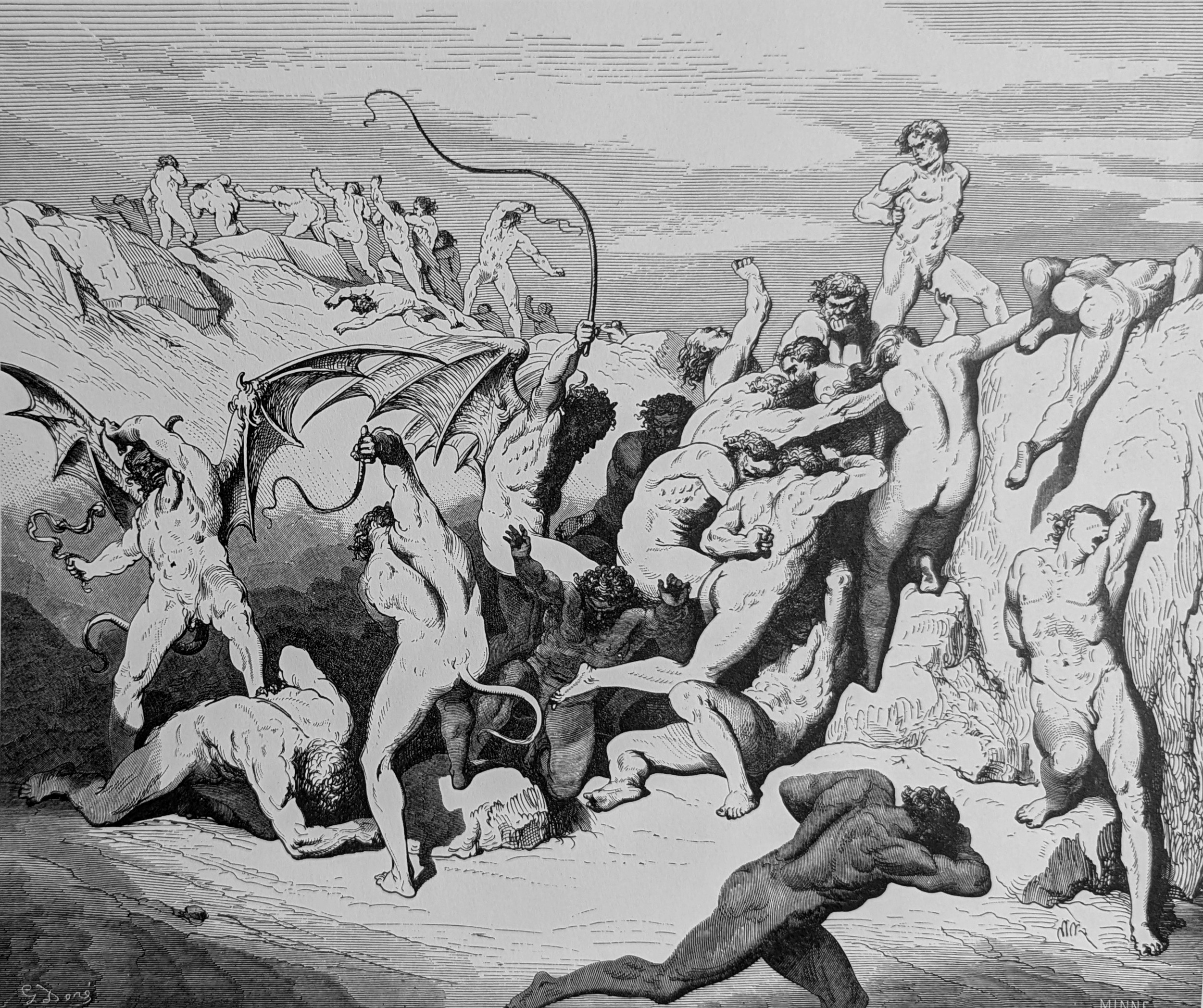

Ah me! how they did make them lift their legs / At the first blows! Inf. XVIII, lines 37-38

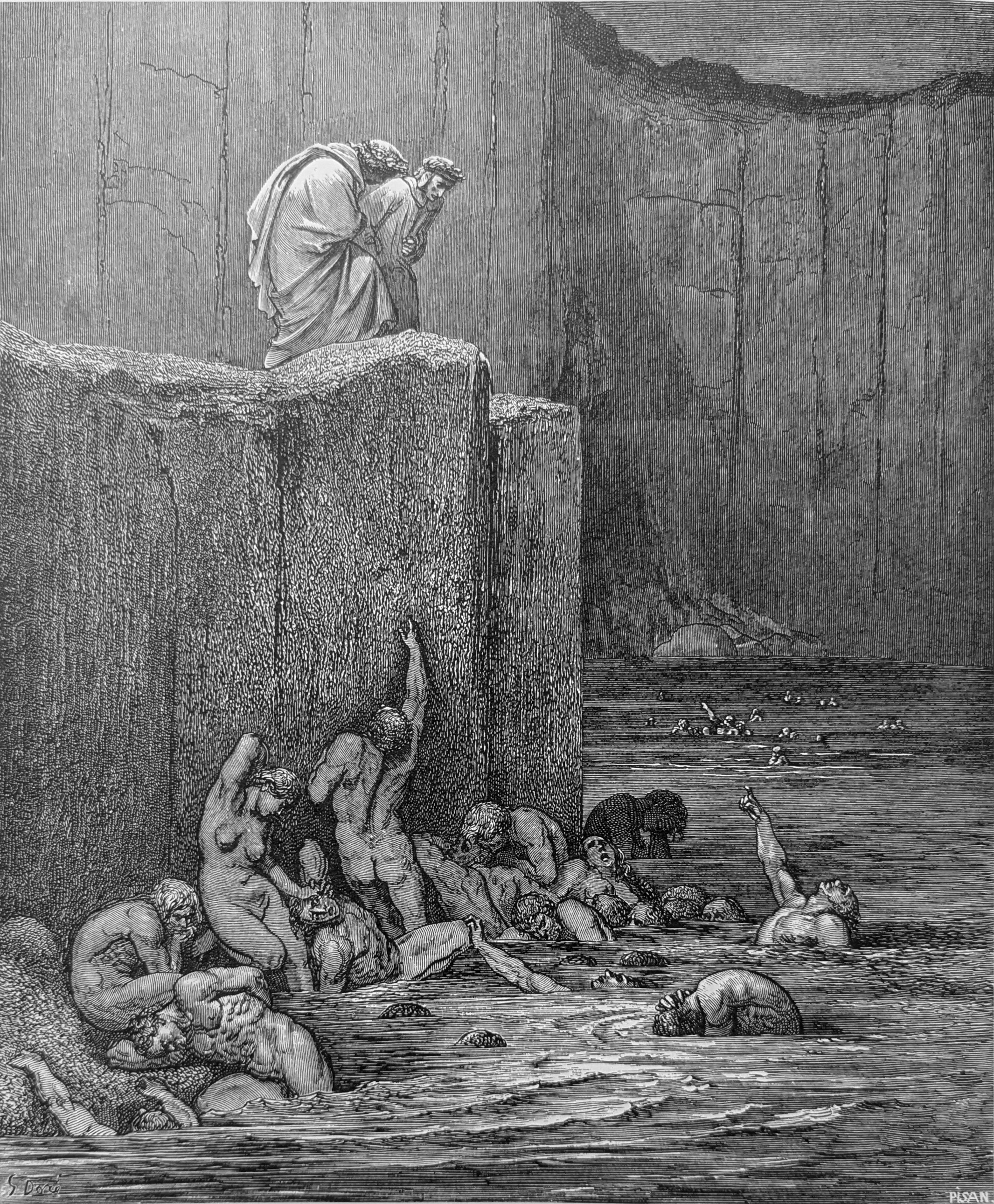

I saw a people smothered in a filth / That out of human privies seemed to flow; Inf. XVIII, lines 113-114

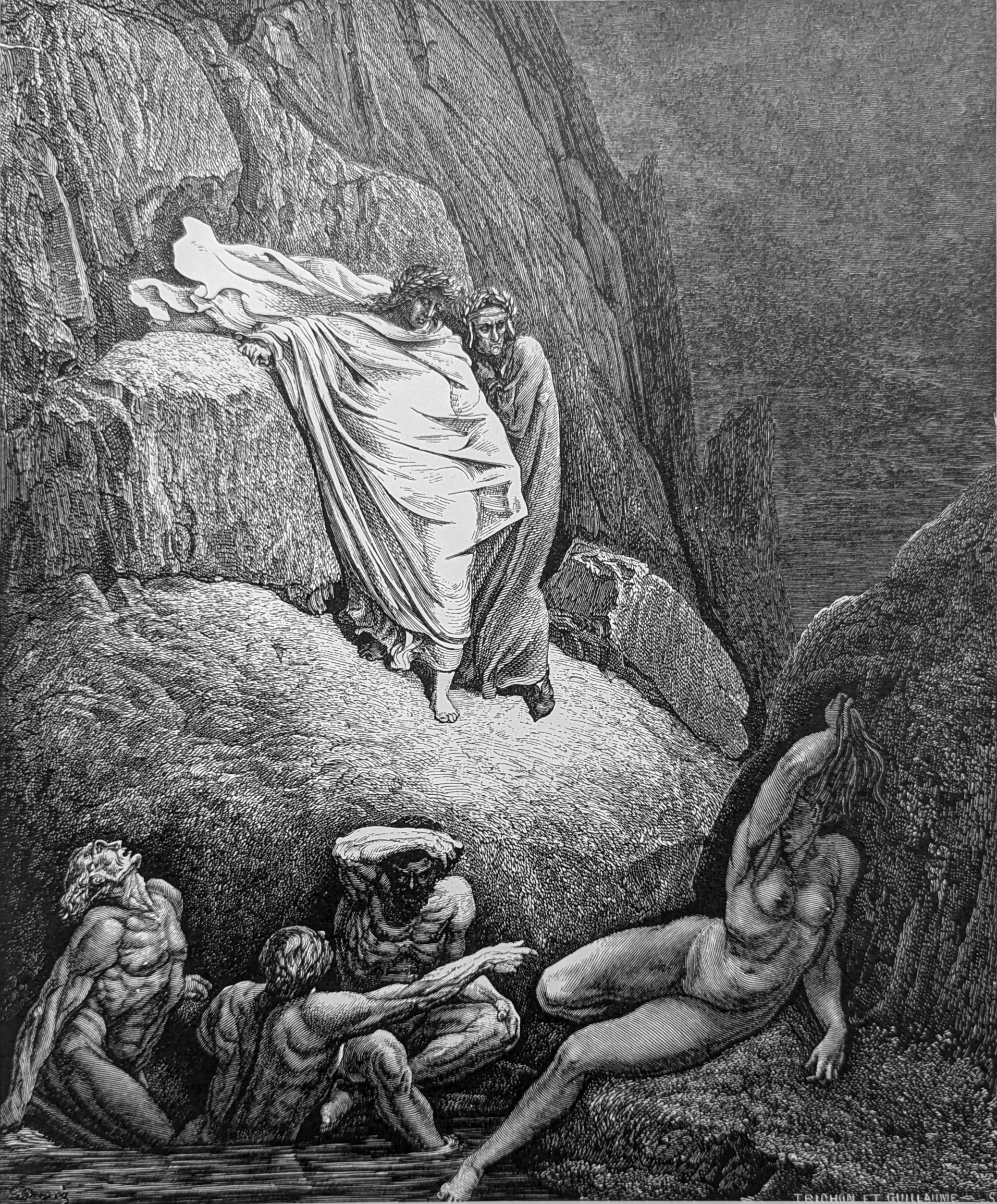

Thais the harlot is it, who replied / Unto her paramour, when he said, 'Have I/ Great gratitude from thee?'—'‘Nay, marvellous;' Inf. XVIII, lines 133-135

Footnotes

1. Dante seems to have invented the Italian word malebolge, which is plural, and means "evil ditches" or pouches, a bolgia being a ditch. The Eighth Circle of Hell (Fraud) is subdivided into ten of these ditches, all filled with sinners being punished for various forms of fraud.

2. In the year 1300, the same year that he sets his poem, Dante's nemesis, Pope Boniface VIII, initiated the Jubilee Year in Rome. The idea of the jubilee is first noted in the Book of Leviticus in the Old Testament (see 25:8-13) where every 50th year was designated as a Jubilee Year. During this year, debts were forgiven, slaves were freed, the land would lie fallow, families who were dispersed would come together, and the whole of Israel invoked and celebrated the mercy of God.

Pope Boniface decreed that everyone who came to Rome for a certain number of days, visited the main churches and basilicas, venerated the relics of the apostles and saints, and confessed and repented of their sins would be given a complete pardon and forgiveness, and many other blessings besides. Dante himself was in Rome during the following year (1301) as part of an embassy from the government of Florence to the Pope, but he was most likely a visitor or pilgrim during the Jubilee to give such a precise description of Roman traffic control here (is there such a thing?). The idea of this Jubilee was extraordinarily popular with Christians throughout Europe. Contemporaries of Dante and other historians note that the Eternal City was thronged with hundreds of thousands of pilgrims during that year. The tradition of the Jubilee Year continues to this day every 25 years.

What connects Dante's memory with the two lines of naked sinners is that in order to control the crowds going to and from St. Peter's Basilica (keep in mind, this is the "original" St. Peter's, not the present one), all those going to the Basilica crossed over the Tiber in front of the Castel Sant'Angelo (the only bridge to that part of Rome in Dante's time) and proceeded toward the Basilica that way. Those returning from St. Peter's were directed to the right along the hillside across the Tiber (probably the area of Monte Goirdano) and passed back toward the bridge by going that way. On this bridge itself the Romans had constructed a barrier down the middle to keep the two groups separated. Those going to St. Peter's passed on the right, and those coming back passed on the left. Keep in mind, also, that construction of the present wide boulevard known as the Via della Conciliazione, which now leads directly from the river to the great piazza in front of the present Basilica was only begun in 1936 by Mussolini and sadly involved the destruction of dozens of structures dating back to the Middle Ages.

3. Dante has seen and identified several notable characters in his travels so far. But Venedico Caccianemico is someone Dante knew and now recognizes, even though he tries to hide his identity—the first sinner to do this and something sinners will do more often from now on. This hiding of identity is definitely an aspect of fraud. Venedico was a contemporary of Dante and a notable figure as the head of the Guelf party in Bologna. He also governed several other Italian cities, among them Milan and Pistoia. He was also accused of murder and harboring criminals. And we will learn something even more terrible as Dante continues. The Poet is obviously surprised to find him in this place and cleverly questions him using Italian slang. When Dante writes, "Ma che ti mena a si pungenti salse?" he's literally asking how Venedico came to find himself in such "pungent sauce." In other words, how did you get yourself into such trouble as this - thus, the "pickle." What's clever is that the Salse is not a reference to "sauce" but to a large garbage dump - a ravine, a bolgia - outside Bologna. Benvenuto da Imola, an early commentator who knew Bologna well tells us that the Salse was a place where, after execution, the bodies of "desperate criminals, usurers, and other unspeakable persons used to be thrown." W.W. Vernon adds that it was a place "where criminals were punished in various ways; where pimps and such like were flogged; where, perhaps, robbers were buried alive head-downwards, and the bodies of excommunicated persons were left unburied."

4. Venedico reveals the terrible sin for which he is now punished. Another way, perhaps, of suggesting that honesty uncovers/ overcomes fraud. In order to curry favor with the Marquis of Este, whom the centaur Nessus pointed out in Canto 12 as one of the tyrants standing quite deeply in the river of boiling blood, Venedico pimped his beautiful sister Ghisola. Apparently, there were many versions of this story, including one which states that this episode is not true. In the end, not only is Venedico forthcoming about his sin, but after he "confesses" to Dante he doesn't hesitate to implicate a huge number of his Bolognese countrymen in the same sin as his own. This bolgia is "stuffed" with them, he says. And when he amplifies this by telling Dante there are more sinners like him than those who say "Sipa," he's referring to the Bolognese dialect where the word sipa means "yes," as in si. What's interesting, though, is that Venedico ends with an appeal to Dante's memory - his memory of the Bolognese as a greedy people. He's just accused a large portion of the population of being pimps and panders, and now he's referring to them as greedy and avaricious. Of course, Dante studied in Bologna, so he probably has a fairly good idea of what Venedico is talking about. But one also begins to wonder about Venedico's objectivity. Dante's plain speech may have gained this sinner's trust. But he's a fraud, and soon enough he's implicating hundreds, not only in his own sin, but in one he's not here for. Would Dante have done better in not reporting these exaggerations, or did he risk the anger of the Bolognese by reporting what one of their citizens told him - whether or not it was true? Interesting questions....

5. In this scene, Virgil tells Dante the story of Jason with a very definite slant against this hero-cum-womanizer. Jason appears in the classical mythology of both Greece and Rome and is the hero of the quest for the golden fleece of Colchis. Deprived of the throne of lolcus by a usurper, Jason was challenged by him to bring back the golden fleece of Colchis, and only then could he take up his rightful place as king. Through many adventures with his band of "Argonauts," he succeeded in capturing the precious prize, but not the throne. The long and convoluted story ends with Jason in grief and reduced to nothing. Virgil highlights a few of the story's major points. The sub-story at Lemnos has it that the women of the island had abandoned the worship of Venus. Insulted by this, the goddess took her revenge on the women by causing them to stink so badly that their revolted husbands abandoned them in disgust. In revenge for this, the women rose up and slew every last man on the island! The princess Hypsipyle, however, lied. She spared her father the king but told everyone else that she had killed him. Some time later, Lemnos was the first stop for the Argonauts on their way to Colchis. As Virgil tells Dante, Jason seduced Hypsipyle and then abandoned her while she was pregnant and continued on his quest for the golden fleece.

The second sub-story involves Medea. When the Argonauts arrived at Colchis, Jason fell in love with Medea, the daughter of King Aeëtes. Not only was she a princess, she was also a sorceress, and if he promised to marry her she promised to help him with her magic arts to steal the golden fleece. Jason succeeded, as we know, but he also repeated what he did to Hypsipyle. He took her with him when he left Colchis, but when he arrived at Corinth, he abandoned her and his two children for Creusa, the daughter of King Creon. In revenge, Medea poisoned Creusa and then murdered her two sons, a final act so savage that Jason seems never to have recovered from it and died in grief. And with this, Virgil abruptly brings their visit to the first bolgia to a close.

6. If Dante was surprised to encounter Venedico Caccianemico in the previous ditch, the surprise here probably has more to do with the clever contrapasso than with the sinner himself, though he, too, deserves mention. As above, Dante the poet anticipates the Pilgrim's encounter with the sinner by giving us a description of this bolgia that's beyond belief. Not so much because it looks like a sink-hole in which we might get a rare view of a broken major sewer line spewing out its contents, but because there are people in it besmirched from head to toe! And, as with most sinners in Hell, we can presume they're naked here as well. Dante is so casual with his curiosity here it's almost laughable, except who among us might not be the same in this circumstance? He wants us to understand that he's always curious and, as we know, only a few times has he been unrewarded. Whether or not the sinner he discovers is a priest or a layman made more sense to a Medieval reader than it might to modern ones who aren't familiar with the old rituals and practices of religious orders. In this case, as a symbol of his intention to move toward ordination, a circle of hair would be shaved off the top of a monk's or candidate's head. This was called the tonsure, and it was generally kept for life. The tonsure easily distinguished men who were clerics or priests from laymen, but Dante has difficulty distinguishing Alessio's status because he seems to be covered with shit from head to toe.

The quick and sassy dialogue between Dante and this flatterer is even more humorous than Dante's being "caught" staring at him. Dante's curiosity and the sinner's embarrassment at being "found our" lead the man to "confess." Alessio Interminei was from a noble family in Lucca who, like Dante, were White Guelfs and thus opposed to the interference of the papacy in civil and political affairs. He was a notorious flatterer as the early commentator, Benvenuto da Imola, writes: "This Alessio had a terrible habit: he was so given to flattery, that he was unable to say anything at all without seasoning it with the oil of adulation. He greased everyone, even the most vile and venal servants. In short, he completely dripped with flattery and stank of it."

7. Knowing his companion's (useful) curiosity and having heard the sass that prompted Alessio's "confession," Virgil urges Dante to lean way out over the bridge to get a look at a scene that is itself way out. Thaïs was the famous mistress of Alexander the Great, but this is not the courtesan Virgil is referring to. This one is the lesser-known lead character—modeled after her more famous counterpart—in a work by the Roman playwright Terence. The flattering words of Thais are quoted by Cicero, and it seems that this is Dante's source here.

This is, without a doubt, the most vulgar scene in Dante's Inferno! And it is Virgil who describes it, not Dante. The Poet's resort to such a repulsive description - whether she was engaged in sexual intercourse, physically defecating, or both, is warranted not only by his personal disgust for the vice of flattery, but for the danger it represented to clarity and reason, not only in social conversation but in the highest matters of statecraft. It is nothing less than fraudulent discourse. In her translation of the Inferno, Dorothy Sayers remarks: "Note that Thais is not here because she is personally a harlot; the sin which has plunged her far below the Lustful, and even below the traffickers in flesh, is the prostitution of words - the medium of intellectual intercourse." And Courtney Langdon, in his translation, adds: Whatever prostitution may be from other points of view, physical or ethical, Dante's marvelous insight saw that it was spiritually poisonous, because essentially it was the most corrupting form of flattery." And, like the previous canto, it is Virgil who brings this disgusting canto to a close.

Top of page