Dante's Divine Comedy: Inferno

Canto XXIX

When Virgil chides his pupil for showering such prolonged attention upon these wretches, Dante argues that he is searching for someone in particular. Virgil swears having seen Geri del Bello, first cousin to Dante's father, pointing a finger at him. The pair continue their discussion of the sinner. In the tenth bolgia, they find all kinds of shrieking, diseased and pestilent Falsifiers, frantically scratching at their sores. Dante converses with two shadows sitting back to back, Griffolino d'Arezzo and Capacchio. The Florentine makes jokes about the Sienese.

The many people and the divers wounds

These eyes of mine had so inebriated,

That they were wishful to stand still and weep;

But said Virgilius: "What dost thou still gaze at?

Why is thy sight still riveted down there

Among the mournful, mutilated shades?

Thou hast not done so at the other Bolge;

Consider, if to count them thou believest,

That two-and-twenty miles the valley winds,

And now the moon is underneath our feet;

Henceforth the time allotted us is brief,

And more is to be seen than what thou seest.[1]

"If thou hadst," I made answer thereupon,

"Attended to the cause for which I looked,

Perhaps a longer stay thou wouldst have pardoned."

Meanwhile my Guide departed, and behind him

I went, already making my reply,

And super-adding: "In that cavern where

I held mine eyes with such attention fixed,

I think a spirit of my blood laments

The sin which down below there costs so much."

Then said the Master: "Be no longer broken

Thy thought from this time forward upon him;

Attend elsewhere, and there let him remain;

For him I saw below the little bridge,

Pointing at thee, and threatening with his finger

Fiercely, and heard him called Geri del Bello.[2]

So wholly at that time wast thou impeded

By him who formerly held Altaforte,

Thou didst not look that way; so he departed."

"O my Conductor, his own violent death,

Which is not yet avenged for him," I said,

"By any who is sharer in the shame,

Made him disdainful; whence he went away,

As I imagine, without speaking to me,

And thereby made me pity him the more."

Thus did we speak as far as the first place

Upon the crag, which the next valley shows

Down to the bottom, if there were more light.

When we were now right over the last cloister

Of Malebolge, so that its lay-brothers

Could manifest themselves unto our sight,

Divers lamentings pierced me through and through,

Which with compassion had their arrows barbed,

Whereat mine ears I covered with my hands.

What pain would be, if from the hospitals

Of Valdichiana, 'twixt July and September,

And of Maremma and Sardinia[3]

All the diseases in one moat were gathered,

Such was it here, and such a stench came from it

As from putrescent limbs is wont to issue.

We had descended on the furthest bank

From the long crag, upon the left hand still,

And then more vivid was my power of sight

Down tow'rds the bottom, where the ministress

Of the high Lord, Justice infallible,

Punishes forgers, which she here records.

I do not think a sadder sight to see

Was in Aegina the whole people sick,

(When was the air so full of pestilence,[4]

The animals, down to the little worm,

All fell, and afterwards the ancient people,

According as the poets have affirmed,

Were from the seed of ants restored again,)

Than was it to behold through that dark valley

The spirits languishing in divers heaps.

This on the belly, that upon the back

One of the other lay, and others crawling

Shifted themselves along the dismal road.

We step by step went onward without speech,

Gazing upon and listening to the sick

Who had not strength enough to lift their bodies.

I saw two sitting leaned against each other,

As leans in heating platter against platter,

From head to foot bespotted o'er with scabs;

And never saw I plied a currycomb

By stable-boy for whom his master waits,

Or him who keeps awake unwillingly,[5]

As every one was plying fast the bite

Of nails upon himself, for the great rage

Of itching which no other succor had.

And the nails downward with them dragged the scab,

In fashion as a knife the scales of bream,

Or any other fish that has them largest.

"O thou, that with thy fingers dost dismail thee,"

Began my Leader unto one of them,

"And makest of them pincers now and then,

Tell me if any Latian is with those

Who are herein; so may thy nails suffice thee

To all eternity unto this work."

"Latians are we, whom thou so wasted seest,

Both of us here," one weeping made reply;

"But who art thou, that questionest about us?"

And said the Guide: "One am I who descends

Down with this living man from cliff to cliff,

And I intend to show Hell unto him."

Then broken was their mutual support,

And trembling each one turned himself to me,

With others who had heard him by rebound.

Wholly to me did the good Master gather,

Saying: "Say unto them whate'er thou wishest."

And I began, since he would have it so:

"So may your memory not steal away

In the first world from out the minds of men,

But so may it survive 'neath many suns,

Say to me who ye are, and of what people;

Let not your foul and loathsome punishment

Make you afraid to show yourselves to me."

"I of Arezzo was," one made reply,

"And Albert of Siena had me burned;

But what I died for does not bring me here.[6]

'Tis true I said to him, speaking in jest,

That I could rise by flight into the air,

And he who had conceit, but little wit,

Would have me show to him the art; and only

Because no Daedalus I made him, made me

Be burned by one who held him as his son.

But unto the last Bolgia of the ten,

For alchemy, which in the world I practiced,

Minos, who cannot err, has me condemned."[7]

And to the Poet said I: "Now was ever

So vain a people as the Sienese?

Not for a certainty the French by far."

Whereat the other leper, who had heard me,

Replied unto my speech: "Taking out Stricca,

Who knew the art of moderate expenses,[8]

And Niccolo, who the luxurious use

Of cloves discovered earliest of all

Within that garden where such seed takes root;

And taking out the band, among whom squandered

Caccia d'Ascian his vineyards and vast woods,

And where his wit the Abbagliato proffered!

But, that thou know who thus doth second thee

Against the Sienese, make sharp thine eye

Tow'rds me, so that my face well answer thee,

And thou shalt see I am Capocchio's shade,

Who metals falsified by alchemy;

Thou must remember, if I well descry thee,

How I a skillful ape of nature was.

Illustrations

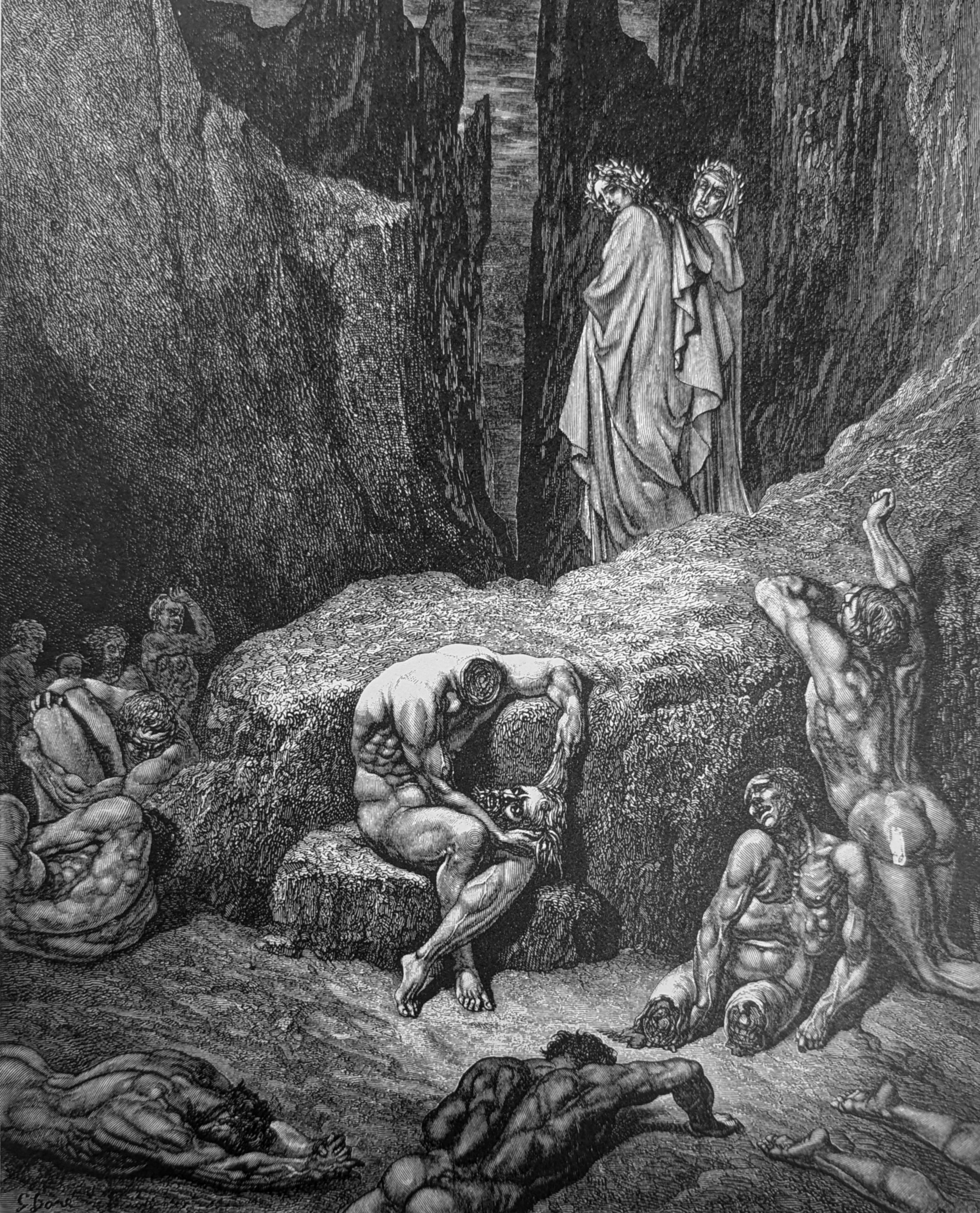

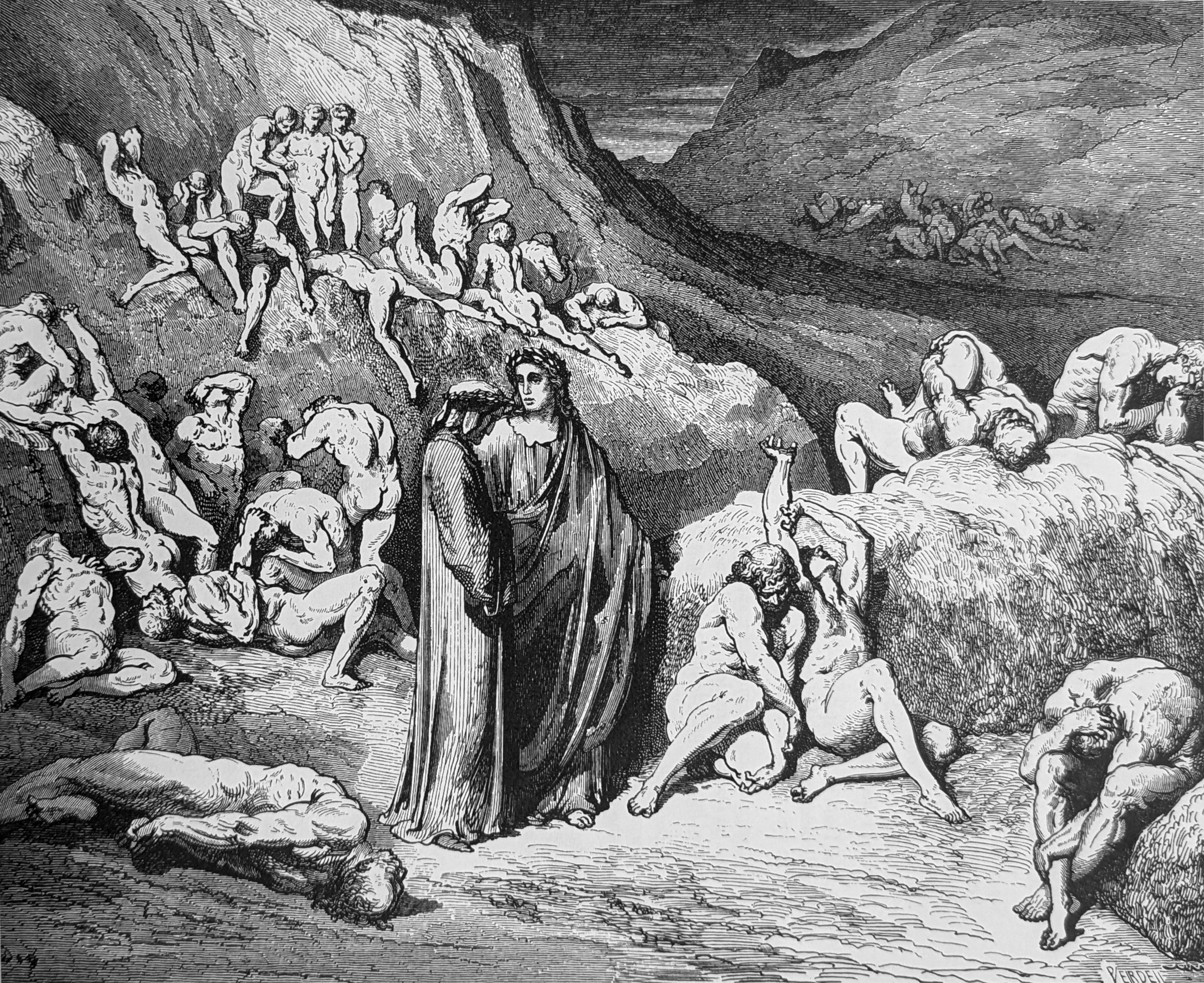

But said Virgilius: "What dost thou still gaze at? / Why is thy sight still riveted down there / Among the mournful, mutilated shades?" Inf. XXIX, lines 4-6

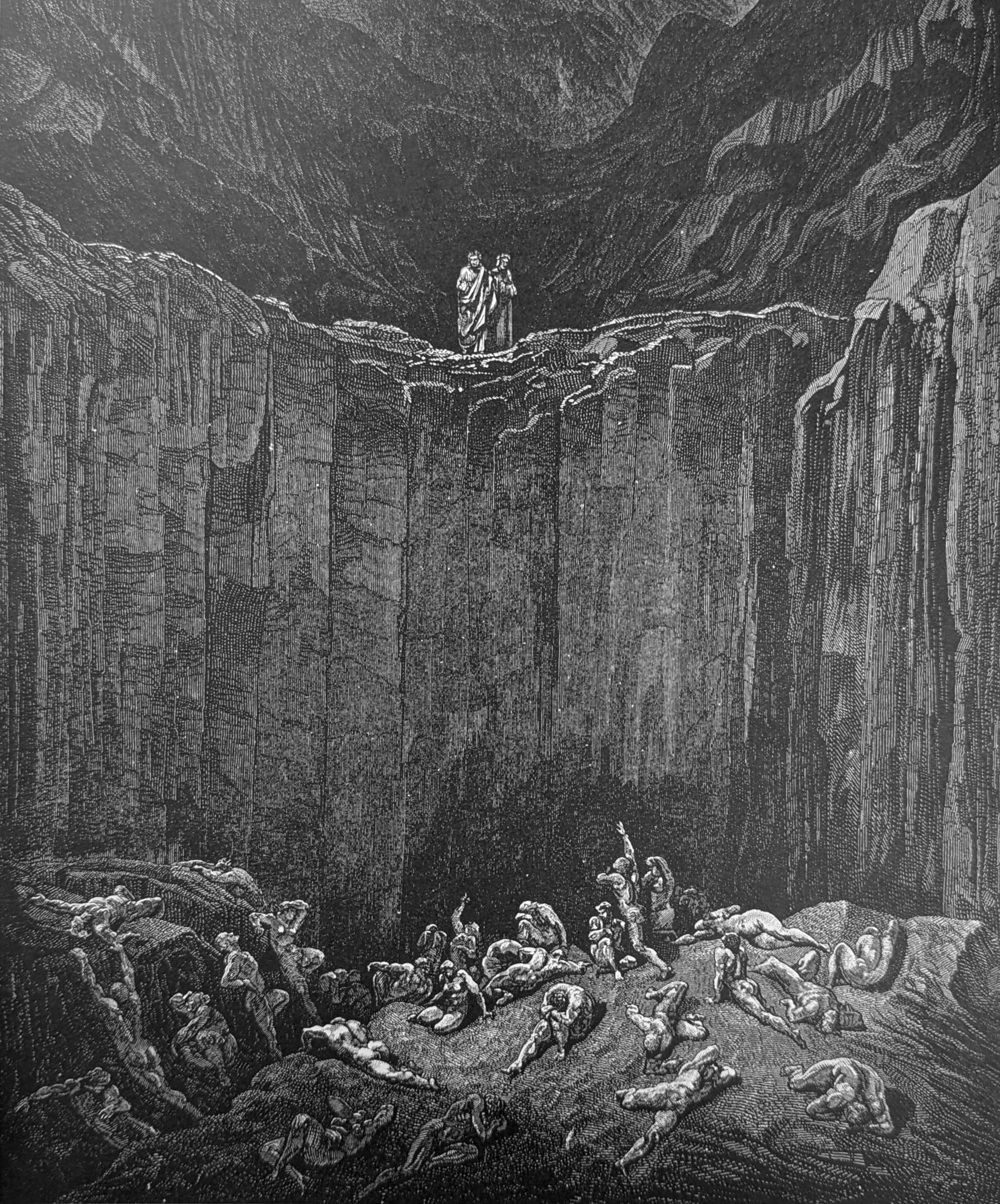

Such a stench came from it / As from putrescent limbs is wont to issue. Inf. XXIX, lines 50-51

Every one was plying fast the bite / Of nails upon himself, for the great rage / Of itching which no other succour had. Inf. XXIX, lines 79-81

Footnotes

1. And as we’ve noted before, time in Hell is told by the position of the moon. If we calculate from the other time references Virgil has made, it’s now about 1:00pm and they’ve been traveling from the dark forest of Canto 1 since 7:00am the previous morning–- about 18 hours.

2. Geri del Bello was a first cousin of Dante’s father, otherwise little else is known about him. He seems to have been a trouble-maker, was involved in a blood feud with the Sacchetti family, and was later murdered by Brodaio dei Sacchetti. By 1300, when the Inferno is set, this murder was not avenged, though it was avenged in 1310. In Dante’s day, vengeance of this kind was both lawful and almost required as a matter of honor. And there seems to have been scriptural backing for it—see Numbers 35:19.

3. Dante is just as specific with names and places here as he was with his list of wars and battles in the previous canto. The Maremma and the Valdichiana (Valley of the Chiana River) are presently rich agricultural regions on the western (Maremma) and eastern (Valdichiana) sides of Tuscany. However, they were not always like this. In Dante’s time, they were covered with swamps and marshes filled with dangerous creatures and breeding grounds for mosquitoes and malaria. Dante died of malaria after traveling through the swampy region of Comacchio between Venice and Ravenna. Like its mainland counterparts, the island of Sardinia in Dante’s time was also known for its disease-filled swamps.

4. Dante immediately begins to see the workings of another of God’s “ministers,” in this case Justice. (Recall Virgil’s explanation of Fortune, a previous “minister.” in Canto 7.) And, we’re also accustomed to his allusion to some past—in this case mythical— event that sets the scene for what he is about to describe. In this case, he borrows a story of the Plague of Aegina from Ovid’s Metamorphoses (VII,523-660). The Greek island of Aegina was named for a nymph who was the daughter of a river god. She fathered a child from Zeus named Aeacus, who later became king of the island. Hera became enraged with jealousy at her husband’s philandering and sent a terrible plague on the island which killed every living thing except Aeacus and the ants. Aeacus prayed to his father for help and Zeus repopulated the island from the ants.

5. Currycomb, used to groom the hoofs of horses.

6. Although this sinner doesn’t give his name, he conveniently provides just enough information about himself that we can identify him as Griffolino d’Arezzo. He was, to quote Benvenuto, “… a man very well versed in the science of nature and in alchemy.” Apparently, he was quite charismatic and glib about his abilities and seems to have duped his rich and credulous friend, Albert, son of the bishop of Siena, into believing he possessed extraordinary powers, and that he could teach the witless man how to fly. The gullible Albert, realizing that his payments for lessons amounted to nothing but words, he denounced Griffolino as a sorcerer to his father, the bishop. In turn, the bishop had Griffolino burned at the stake. The unwary Albert was apparently from a noble and wealthy Sienese family, and commentators seem to be divided as to whether he was the natural son of the bishop or whether he was adopted. In addition, we have no specific dates for Griffolino other than his name appearing in a Bolognese document dated 12 59.

7. Griffolino, who really has no reason to be honest, tells Dante twice that he’s not in Hell for sorcery or, at least, the kind of magical alchemy that would have landed him in the fourth bolgia with the fortune-tellers. Instead, he’s really here for the kind of alchemy that falsified baser metals as silver and gold. This sets a nice contrast between human justice which may be faulty (his execution for the wrong charge), and divine Justice which is always correct, as Griffolino indicates in his allusion to Minos. Humorously, the Anonimo Fiorentino records this conversation between Albert and Griffolino, who pointed out to him one of the particular advantages of being able to fly: “You see, Albero, there are few things I cannot do. If I wanted to, I could teach yo u to fly. Then, if there were any woman in Siena you liked, you could fly into her house through the window.” While this is comical, it is also an outright lie hidden in the humor here, and it is this kind of falsification of language is what lands Griffoli no here in Hell. Of course, there is a dark humor in this canto (and the next one) that will lead Dante to remark how silly the Sienese are, followed by more gossipy information freely proffered by the other Italian sinner. All of this will be climaxed by t he great “cat fight” that ends Canto 30. The reader must understand, of course, that Dante the Poet allows the Pilgrim to participate in this foolish “mis-“use of language as part of his strategy to present the subtlety of counterfeiting and falsification o f all kinds.

8. Capocchio tells us about more than himself. He agrees with Dante that the Sienese are effete, but sarcastically excepts several men who may have been his companions and members of the notorious Brigata Spendereccia or “Spendthrift’s Brigade.” This group was made up of twelve young, very wealthy rascals who sought to outdo each other in extravagantly wasting their money. It wasn’t long before they ended up as paupers. We know hardly anything else about them. Stricca, or Baldastricca di Giovanni de’Salimbeni, was apparently a Sienese lawyer and Podestà of Bologna for some time, and Niccolò had gourmet tastes. About Caccia d’Asciano and Abbagliato we know hardly anything. Caccia apparently squandered a fortune in vineyards and property. Abbagliato is a nickname which means “dazed.” Musa seems to be alone among scholars who adds this information about him.

Top of page