Dante's Divine Comedy: Paradiso

Canto XXI

On entering Saturn, the last of the planets, Beatrice avoids smiling because at this level Dante's mortal senses would not be able to cope with her radiance. Dante beholds a golden ladder on which countless splendors, the souls of the Contemplatives, ascend and descend like birds in flight. Saint Peter Damiano, renowned doctor of the Church and severe Benedictine ascetic, draws near. He indicates the unfathomable depths of the mystery of predestination and denounces the indulgent lifestyle of prelates. The other souls gather around him before sending forth a mighty cry of anger to express Heaven's indignation at such laxity.

Already on my Lady's face mine eyes

Again were fastened, and with these my mind,

And from all other purpose was withdrawn;

And she smiled not; but "If I were to smile,"

She unto me began, "thou wouldst become

Like Semele, when she was turned to ashes.[1]

Because my beauty, that along the stairs

Of the eternal palace more enkindles,

As thou hast seen, the farther we ascend,

If it were tempered not, is so resplendent

That all thy mortal power in its effulgence

Would seem a leaflet that the thunder crushes.

We are uplifted to the seventh splendor,

That underneath the burning Lion's breast

Now radiates downward mingled with his power.

Fix in direction of thine eyes the mind,

And make of them a mirror for the figure

That in this mirror shall appear to thee."

He who could know what was the pasturage

My sight had in that blessed countenance,

When I transferred me to another care,

Would recognize how grateful was to me

Obedience unto my celestial escort,

By counter-poising one side with the other.

Within the crystal which, around the world

Revolving, bears the name of its dear leader,

Under whom every wickedness lay dead,

Coloured like gold, on which the sunshine gleams,

A stairway I beheld to such a height

Uplifted, that mine eye pursued it not.

Likewise beheld I down the steps descending

So many splendors, that I thought each light

That in the heaven appears was there diffused.

And as accordant with their natural custom

The rooks together at the break of day

Bestir themselves to warm their feathers cold;[2]

Then some of them fly off without return,

Others come back to where they started from,

And others, wheeling round, still keep at home;

Such fashion it appeared to me was there

Within the sparkling that together came,

As soon as on a certain step it struck,

And that which nearest unto us remained

Became so clear, that in my thought I said,

"Well I perceive the love thou showest me;

But she, from whom I wait the how and when

Of speech and silence, standeth still; whence I

Against desire do well if I ask not."

She thereupon, who saw my silentness

In the sight of Him who seeth everything,

Said unto me, "Let loose thy warm desire."

And I began: "No merit of my own

Renders me worthy of response from thee;

But for her sake who granteth me the asking,

Thou blessed life that dost remain concealed

In thy beatitude, make known to me

The cause which draweth thee so near my side;

And tell me why is silent in this wheel

The dulcet symphony of Paradise,

That through the rest below sounds so devoutly."

"Thou hast thy hearing mortal as thy sight,"

It answer made to me; "they sing not here,

For the same cause that Beatrice has not smiled.

Thus far adown the holy stairway's steps

Have I descended but to give thee welcome

With words, and with the light that mantles me;

Nor did more love cause me to be more ready,

For love as much and more up there is burning,

As doth the flaming manifest to thee.

But the high charity, that makes us servants

Prompt to the counsel which controls the world,

Allotteth here, even as thou dost observe."

"I see full well," said I, "O sacred lamp!

How love unfettered in this court sufficeth

To follow the eternal Providence;

But this is what seems hard for me to see,

Wherefore predestinate wast thou alone

Unto this office from among thy consorts."

No sooner had I come to the last word,

Than of its middle made the light a center,

Whirling itself about like a swift millstone.

When answer made the love that was therein:

"On me directed is a light divine,

Piercing through this in which I am embosomed,

Of which the virtue with my sight conjoined

Lifts me above myself so far, I see

The supreme essence from which this is drawn.

Hence comes the joyfulness with which I flame,

For to my sight, as far as it is clear,

The clearness of the flame I equal make.

But that soul in the heaven which is most pure,

That seraph which his eye on God most fixes,

Could this demand of thine not satisfy;

Because so deeply sinks in the abyss

Of the eternal statute what thou askest,

From all created sight it is cut off.

And to the mortal world, when thou returnest,

This carry back, that it may not presume

Longer tow'rd such a goal to move its feet.

The mind, that shineth here, on Earth doth smoke;

From this observe how can it do below

That which it cannot though the heaven assume it?"

Such limit did its words prescribe to me,

The question I relinquished, and restricted

Myself to ask it humbly who it was.

"Between two shores of Italy rise cliffs,

And not far distant from thy native place,

So high, the thunders far below them sound,

And form a ridge that Catria is called,

'Neath which is consecrate a hermitage

Wont to be dedicate to worship only."[3]

Thus unto me the third speech recommenced,

And then, continuing, it said: "Therein

Unto God's service I became so steadfast,

That feeding only on the juice of olives

Lightly I passed away the heats and frosts,

Contented in my thoughts contemplative.

That cloister used to render to these heavens

Abundantly, and now is empty grown,

So that perforce it soon must be revealed.

I in that place was Peter Damiano;

And Peter the Sinner was I in the house

Of Our Lady on the Adriatic shore.[4]

Little of mortal life remained to me,

When I was called and dragged forth to the hat

Which shifteth evermore from bad to worse.

Came Cephas, and the mighty Vessel came

Of the Holy Spirit, meager and barefooted,

Taking the food of any hostelry.[5]

Now some one to support them on each side

The modern shepherds need, and some to lead them,

So heavy are they, and to hold their trains.

They cover up their palfreys with their cloaks,

So that two beasts go underneath one skin;

O Patience, that dost tolerate so much!"[6]

At this voice saw I many little flames

From step to step descending and revolving,

And every revolution made them fairer.

Round about this one came they and stood still,

And a cry uttered of so loud a sound,

It here could find no parallel, nor I

Distinguished it, the thunder so o'ercame me.

Footnotes

1. Images of seeing and hearing are used throughout Paradise to indicate Dante's receptivity to God's grace. The pilgrim-poet is frequently dazed—and in one case, temporarily but completely blinded—by the brightness of the souls he meets. These are mere reflections of God's glory, so Dante's situation is akin to viewing God through a camera obscura, yet still being dazzled by the light. Likewise, Dante is enraptured by the songs these souls sing, but he is often overpowered by their beauty and sometimes unable to discern their words. Being a human in Paradise is, as Dante portrays it, a constant experience of too-muchness. Spiritual progress is measured by one's ability to adapt.

Canto 21 underscores the extreme nature of Dante's sensory experiences in Paradise. He learns there are sights so bright as to be not just disorienting, but harmful—as Beatrice's radiance would become if she smiled. The notion of God being too bright to be hold is widespread among the world's religions. Paul, in his first epistle to Timothy, gives this idea its definitive expression in the Christian context:

God only hath immortality, dwelling in the light which no man can approach unto; whom no man hath seen, nor can see.

Beatrice, however, is a mere spark or glint of this "unapproachable light," as are the rest of the saints. If she can immolate Dante with a smile, his spiritual vision must therefore be relatively weak and easily overpowered. Yet vision, for Dante, is not merely the ability to tolerate bright lights. It also involves the ability to discern fine details, even at a great distance. In this sense, too, Dante's vision is still limited since he cannot see the end of the contemplatives' ladder. By the time he reaches the Empyrean, his sight will be so purified and perfected that everything will appear in total clarity. He is moving back in time and moving higher all the time, into ever more rarified atmosphere preparatory to God and the final destination.

Semele was the youngest daughter of Cadmus and Harmonia, and the mother of Dionysus by Zeus.

Certain elements of the cult of Dionysus and Semele came from the Phrygians. These were modified, expanded, and elaborated by the Ionian Greek colonists. Doric Greek historian Herodotus (484–425 BC), born in the city of Halicarnassus under the Achaemenid Empire, who gives the account of Cadmus, estimates that Semele lived either 1,000 or 1,600 years prior to his visit to Tyre in 450 BC at the end of the Greco-Persian Wars (499–449 BC) or around 2050 or 1450 BC. In Rome, the goddess Stimula was identified as Semele. Semele was the subject of the now lost tragedy by Aeschylus called Semele (Σεμέλη) or Wool-Carders (Ξάντριαι).

In one version of the myth, Semele was a priestess of Zeus, and on one occasion was observed by Zeus as she slaughtered a bull at his altar and afterwards swam in the river Asopus to cleanse herself of the blood. Flying over the scene in the guise of an eagle, Zeus fell in love with Semele and repeatedly visited her secretly.

Zeus's wife, Hera, a goddess jealous of usurpers, discovered his affair with Semele when she later became pregnant. Appearing as an old crone, Hera befriended Semele, who confided in her that her lover was actually Zeus. Hera pretended not to believe her, and planted seeds of doubt in Semele's mind. Curious, Semele asked Zeus to grant her a boon. Zeus, eager to please his beloved, promised on the River Styx to grant her anything she wanted. She then demanded that Zeus reveal himself in all his glory as proof of his divinity. Though Zeus begged her not to ask this, she persisted and he was forced by his oath to comply. Zeus tried to spare her by showing her the smallest of his bolts and the sparsest thunderstorm clouds he could find. Mortals, however, cannot loo k upon the gods without incinerating, and she perished, consumed in a lightning-ignited flame.

Zeus is the chief god in Greek mythology, ruling over Mount Olympus as the god of the sky and thunder.

Jupiter is the Roman equivalent of Zeus, adapted from Greek mythology into Roman culture.

Both gods are considered "sky fathers," with their names reflecting this role. Zeus is often referred to as "Zeus Pater," while Jupiter is derived from "Diespiter," meaning "Sky Father." Zeus is depicted as a strong, bearded man, while Jupiter's appearance is less defined in Roman art. Zeus is the son of Cronus and Rhea, while Jupiter is the son of Saturn and Ops, reflecting their respective mythological lineages. Both gods have similar family structures, with Jupiter being the brother of Neptune (Poseidon) and Pluto (Hades), paralleling Zeus's relationships in Greek mythology.

2. rook, a European bird, Corvus frugilegus, of the crow family.

3. Monte Catria is a mountain in the central Apennines, in the province of Pesaroe Urbino, Marche, central Italy. The highest peak is at 1,702 meters above sea level. It is a massif of limestone rocks dating to some 200 million years ago. Historically, it marked the boundary between the Exarchate of Ravenna and the Duchy of Spoleto The source of the Cesano river is located nearby.

4. Saint Peter Damiano, also known as Peter Damian (1007–1073 AD) was an Italian reforming Benedictine monk and cardinal in the circle of Pope Leo IX. Dante placed him in one of the highest circles of Paradiso as a great predecessor of Francis of Assisi an d he was declared a Doctor of the Church in 1828.

Peter was born in Ravenna around 1007, the youngest of a large but poor noble family. Orphaned early, he was at first adopted by an elder brother who ill-treated and under-fed him while employing him as a swineherd. After some years, another brother, Damian us, who was arch-priest at Ravenna, had pity on him and took him away to be educated. Adding his brother's name to his own, Peter made such rapid progress in his studies of theology and canon law, first at Ravenna, then at Faenza, and finally at the University of Parma, that, around the age of 25, he was already a famous teacher at Parma and Ravenna.

5. Cephas, also known as Saint Peter, is a significant figure in Christian tradition. He is one of the twelve apostles of Jesus and is often regarded as the first Pope. Cephas represents the Church's authority and the foundation of Christian faith. Cephas is mentioned in relation to the themes of spiritual leadership and the Church's role in guiding souls. His presence underscores the importance of divine guidance and the moral responsibilities of those in positions of power within the Church. Cephas symbolizes the transition from earthly to heavenly authority. His mention in this canto highlights the contrast between the spiritual purity of the heavenly realm and the corruption that can occur within the Church on Earth. This reflects Dante's concerns about the state of the Church during his time. Cephas serves as a reminder of the ideal of humility and service that should characterize true leadership in the Christian faith.

6. palfrey, Anglo-Norman palefrei, “steed”, French palefroi, palefreid, Latin paraverēdus, “post horse, spare horse”, Greek+Latin, παρά (pará) + verēdus (“post horse”). A small horse with a smooth, ambling gait, popular in the Middle Ages with nobles and women for riding, contrasted with a warhorse.

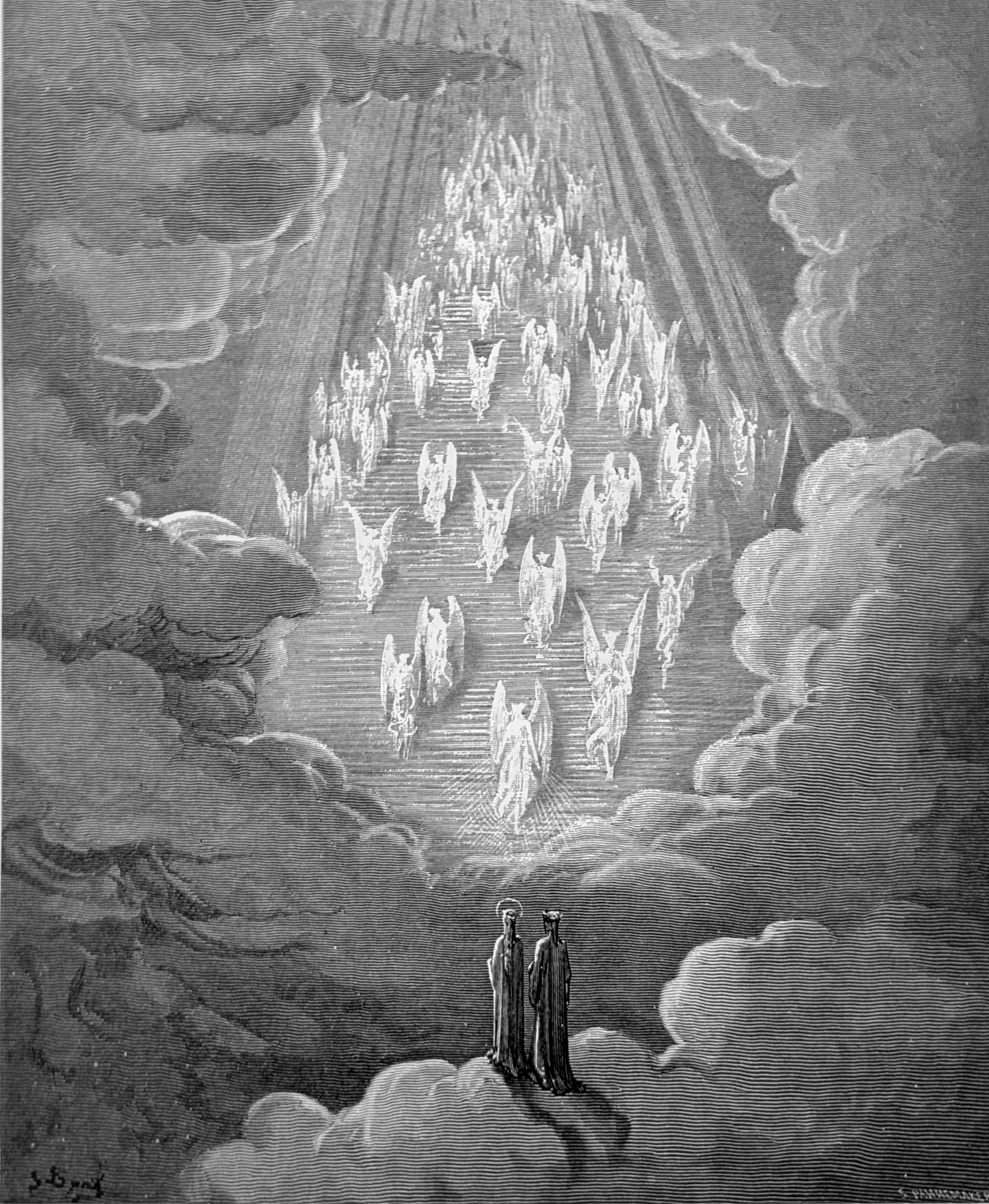

Illustrations of Paradiso

Already on my Lady's face mine eyes / Again were fastened. Par. XXI, lines 1-2

A stairway I beheld to such a height / Uplifted, that mine eye pursued it not. Par. XXI, lines 29-30

Top of page