Dante's Divine Comedy: Paradiso

Canto V

The stories of Piccarda and Constance have raised the subject of vows and how best to obey them. Impressed by the illuminated state of Dante's mind, Beatrice declares that every vow to God is defined by two aspects: the thing sworn and the surrender of one's will. The latter condition underpins everything but the content of what is pledged may be altered, provided that an individual gives up something even dearer in exchange. Beatrice and Dante ascend into the Second Heaven, the sphere of Mercury, where crowds of luminous souls flock to them. Beatrice urges Dante to question one of them.

"If in the heat of love I flame upon thee

Beyond the measure that on Earth is seen,

So that the valour of thine eyes I vanquish,

Marvel thou not thereat; for this proceeds

From perfect sight, which as it apprehends

To the good apprehended moves its feet.

Well I perceive how is already shining

Into thine intellect the eternal light,

That only seen enkindles always love;

And if some other thing your love seduce,

'Tis nothing but a vestige of the same,

Ill understood, which there is shining through.

Thou fain wouldst know if with another service

For broken vow can such return be made

As to secure the soul from further claim."

This Canto thus did Beatrice begin;

And, as a man who breaks not off his speech,

Continued thus her holy argument:

"The greatest gift that in his largess God

Creating made, and unto his own goodness

Nearest conformed, and that which he doth prize

Most highly, is the freedom of the will,

Wherewith the creatures of intelligence

Both all and only were and are endowed.

Now wilt thou see, if thence thou reasonest,

The high worth of a vow, if it he made

So that when thou consentest God consents:

For, closing between God and man the compact,

A sacrifice is of this treasure made,

Such as I say, and made by its own act.

What can be rendered then as compensation?

Think'st thou to make good use of what thou'st offered,

With gains ill gotten thou wouldst do good deed.[1]

Now art thou certain of the greater point;

But because Holy Church in this dispenses,

Which seems against the truth which I have shown thee,

Behoves thee still to sit awhile at table,

Because the solid food which thou hast taken

Requireth further aid for thy digestion.

Open thy mind to that which I reveal,

And fix it there within; for 'tis not knowledge,

The having heard without retaining it.

In the essence of this sacrifice two things

Convene together; and the one is that

Of which 'tis made, the other is the agreement.

This last for evermore is cancelled not

Unless complied with, and concerning this

With such precision has above been spoken.

Therefore it was enjoined upon the Hebrews

To offer still, though sometimes what was offered

Might be commuted, as thou ought'st to know.

The other, which is known to thee as matter,

May well indeed be such that one errs not

If it for other matter be exchanged.

But let none shift the burden on his shoulder

At his arbitrament, without the turning

Both of the white and of the yellow key;[2]

And every permutation deem as foolish,

If in the substitute the thing relinquished,

As the four is in six, be not contained.

Therefore whatever thing has so great weight

In value that it drags down every balance,

Cannot be satisfied with other spending.

Let mortals never take a vow in jest;

Be faithful and not blind in doing that,

As Jephthah was in his first offering,[3]

Whom more beseemed to say, 'I have done wrong,

Than to do worse by keeping; and as foolish

Thou the great leader of the Greeks wilt find,

Whence wept Iphigenia her fair face,

And made for her both wise and simple weep,

Who heard such kind of worship spoken of.'[4]

Christians, be ye more serious in your movements;

Be ye not like a feather at each wind,

And think not every water washes you.

Ye have the Old and the New Testament,

And the Pastor of the Church who guideth you

Let this suffice you unto your salvation.

If evil appetite cry aught else to you,

Be ye as men, and not as silly sheep,

So that the Jew among you may not mock you.

Be ye not as the lamb that doth abandon

Its mother's milk, and frolicsome and simple

Combats at its own pleasure with itself."

Thus Beatrice to me even as I write it;

Then all desireful turned herself again

To that part where the world is most alive.

Her silence and her change of countenance

Silence imposed upon my eager mind,

That had already in advance new questions;

And as an arrow that upon the mark

Strikes ere the bowstring quiet hath become,

So did we speed into the second realm.

My Lady there so joyful I beheld,

As into the brightness of that heaven she entered,

More luminous thereat the planet grew;

And if the star itself was changed and smiled,

What became I, who by my nature am

Exceeding mutable in every guise!

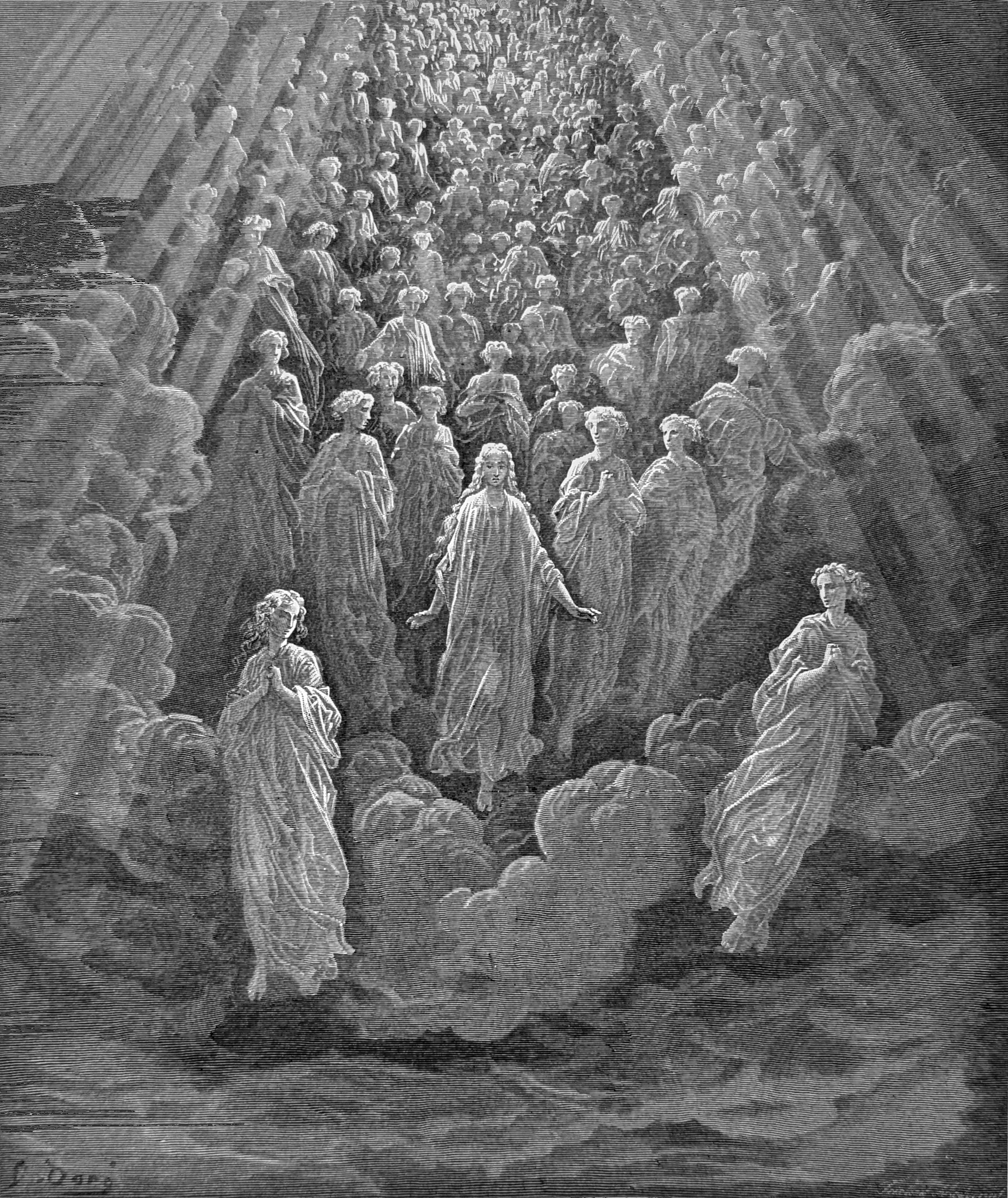

As, in a fish-pond which is pure and tranquil,

The fishes draw to that which from without

Comes in such fashion that their food they deem it;

So I beheld more than a thousand splendours

Drawing towards us, and in each was heard:

"Lo, this is she who shall increase our love."

And as each one was coming unto us,

Full of beatitude the shade was seen,

By the effulgence clear that issued from it.

Think, Reader, if what here is just beginning

No farther should proceed, how thou wouldst have

An agonizing need of knowing more;

And of thyself thou'lt see how I from these

Was in desire of hearing their conditions,

As they unto mine eyes were manifest.

"O thou well-born, unto whom Grace concedes

To see the thrones of the eternal triumph,

Or ever yet the warfare be aabandoned

With light that through the whole of heaven is spread

Kindled are we, and hence if thou desirest

To know of us, at thine own pleasure sate thee."

Thus by some one among those holy spirits

Was spoken, and by Beatrice: "Speak, speak

Securely, and believe them even as Gods."

"Well I perceive how thou dost nest thyself

In thine own light, and drawest it from thine eyes,

Because they coruscate when thou dost smile,[5]

But know not who thou art, nor why thou hast,

Spirit august, thy station in the sphere

That veils itself to men in alien rays."[6]

This said I in direction of the light

Which first had spoken to me; whence it became

By far more lucent than it was before.

Even as the sun, that doth conceal himself

By too much light, when heat has worn away

The tempering influence of the vapours dense,[7]

By greater rapture thus concealed itself

In its own radiance the figure saintly,

And thus close, close enfolded answered me

In fashion as the following Canto sings.

Footnotes

1. This canto contains some strikingly legalistic language: in describing the nature of sacred vows, Beatrice speaks of charges, liabilities, and recompense. Then, in explaining why certain vows cannot be broken without sinning, she resorts to the metaphor of monetary payment, complete with concepts of interest and penalty. Like the images of stars and planets, these terms are best thought of as allegorical, helping to bring the issue into focus. God does not, as Dante imagines Him, sit at His desk like a bookke eper or accountant, poring over a ledger of moral obligations. He is not stingy or vindictive, as the emphasis on payment might suggest. Rather, money imagery is a convenient symbol, used to show the exactness with which promises—including vows—must be fu lfilled.

Legal and financial metaphors are just some of the tools Dante uses to try to understand God's justice, which operates very differently from earthly justice. The distinction between the two—the seeming unfairness of God's actions when weighed in human term s—is a major preoccupation of the Divine Comedy. In a sense the problem is more acute in Paradise than in Purgatory or Hell because the logic of crime and punishment is less obvious. Those who obtain a smaller share of God's grace in Heaven are not "pu nished" in the same way as, say, a thief perpetually devoured by serpents earlier in the Commedia was. Nonetheless, Dante is troubled by the notion of a soul losing anything through what appears to be an innocent or involuntary act. He does not, to his cred it, give up trying to untangle this problem, even when it leads him into one impenetrable mystery after another. The Florentine society Dante came from was known as a world capital of money and finance, and its citizens were famous for their attachment to m oney and trade. So in answering this important question about human and divine natures, it is not surprising for the poet to use a monetary metaphor.

2. In Dante's Paradiso, the colors white and yellow symbolize different virtues and states of being. White often represents purity and divine grace, while yellow can signify ambition or earthly desires, particularly in the context of the souls Dante encounters in the celestial spheres.

Symbolism of Colors in Dante's Paradiso

White Key

- Purity and Divine Light: The white key often symbolizes purity, innocence, and divine light. In the context of Paradiso, it represents the souls who have achieved a high level of grace and are close to God.

- Connection to Virtue: White is associated with the virtues that Dante emphasizes throughout his journey, particularly the theological virtues of Faith, Hope, and Charity.

Yellow Key

- Ambition and Earthly Glory: The yellow key can symbolize ambition and the pursuit of earthly glory. In Paradiso, it may represent those who sought fame and recognition but lacked true virtue.

- Conflict and Division: Yellow is also linked to the historical conflicts in Dante's time, particularly the Guelphs and Ghibellines. It reflects the struggles for power and the moral failings associated with such ambitions.

3. Jephthah appears in the Book of Judges as a judge who presided over Israel for a period of six years (Judges 12:7). According to Judges, he lived in Gilead. His father's name is also given as Gilead, and, as his mother is described as a prostitute, this may indicate that his father might have been any of the men of that area. Jephthah led the Israelites in battle against Ammon and, in exchange for defeating the Ammonites, made a vow to sacrifice whatever would come out of the door of his house first. When his daughter was the first to come out of the house, he immediately regretted the vow, which bound him to sacrifice his daughter to God. Jephthah carried out his vow.

4. In Greek mythology, Iphigenia was a daughter of King Agamemnon and Queen Clytemnestra, and thus a princess of Mycenae.

Agamemnon offends the goddess Artemis on his way to the Trojan War by hunting and killing one of Artemis's sacred stags. Artemis retaliates by preventing the allied troops from reaching Troy unless Agamemnon kills his eldest daughter, Iphigenia, at Aulis as a human sacrifice. In some versions, Iphigenia dies at Aulis, and in others, Artemis rescues her. In the version where she is saved, she goes to the Taurians and meets her brother Orestes.

5. coruscate, Latin, coruscātus, coruscō + ate, “to flash, gleam” + verb-suffix.

6. august, Latin, augustus, “majestic, venerable, imperial, royal”), augeō, “to augment, increase; to expand”.

7. Because of its proximity to the sun, the planet Mercury is often difficult to see. Allegorically, the planet represents those who did good out of a desire for fame, but who, being ambitious, were deficient in the virtue of justice. Their earthly glory pales into insignificance beside the glory of God, just as Mercury pales into insignificance beside the sun.

Illustrations of Paradiso

So I beheld more than a thousand splendours / Drawing towards us, Par V, lines 103-104

Top of page