Dante's Divine Comedy: Paradiso

Canto XIX

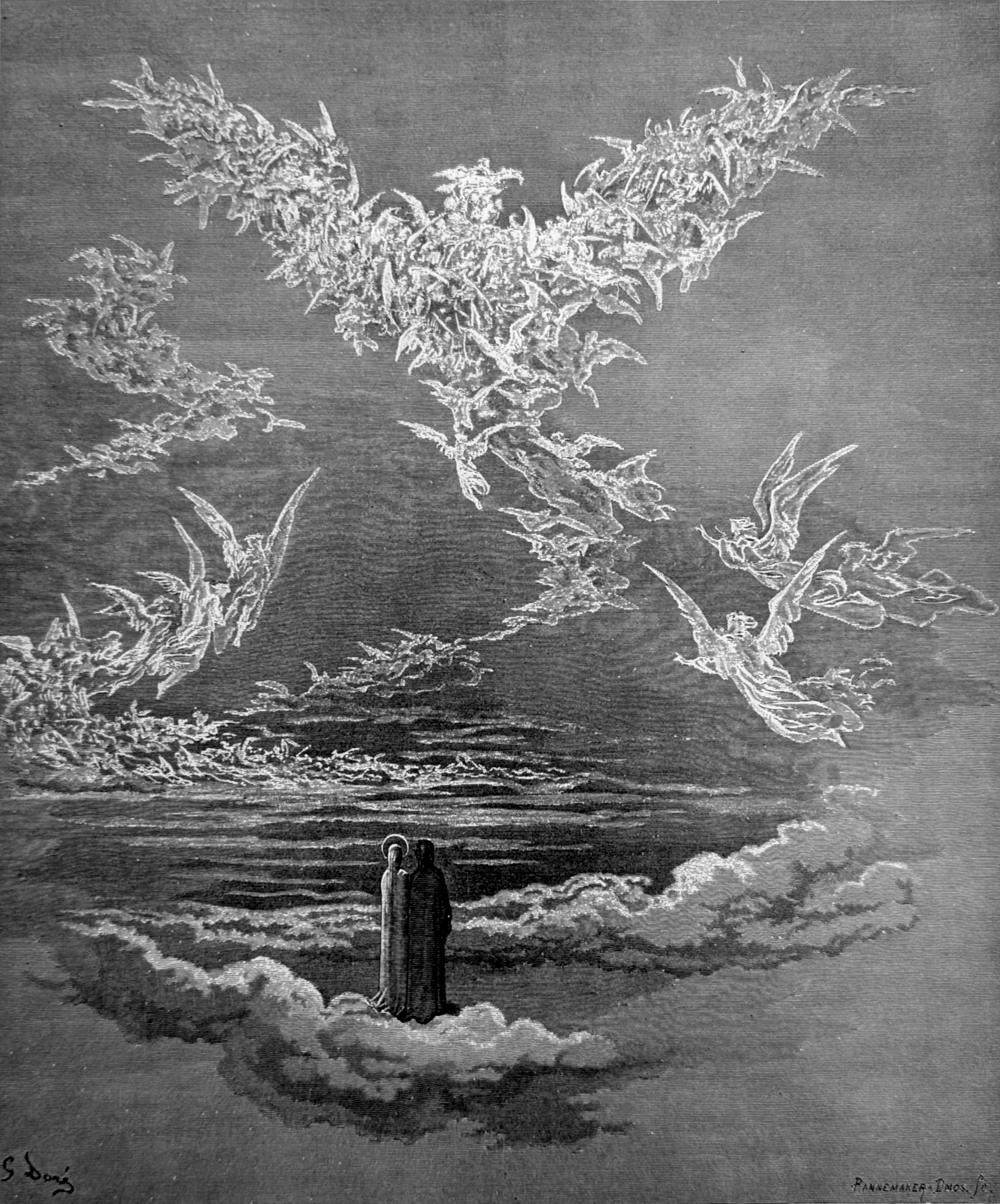

An eagle appears. Its image is made up of many rubies each representing a soul. Its voice speaks for all the souls within it, who had left examples of justice on Earth that were not followed. Dante asks whether the souls of virtuous heathens are excluded from heavenly bliss. The eagle replies that mankind cannot expect to understand the workings of divine justice and should only question whether God's judgments conform to His will not whether they are fair—because our concept of justice is but a poor reflection of God's infallible standard. Evil, contemporary monarchs, such as Albert of Austria and Philip IV of France, are openly condemned.

Appeared before me with its wings outspread

The beautiful image that in sweet fruition

Made jubilant the interwoven souls;

Appeared a little ruby each, wherein

Ray of the sun was burning so enkindled

That each into mine eyes refracted it.

And what it now behooves me to retrace

Nor voice has e'er reported, nor ink written,

Nor was by fantasy e'er comprehended;

For speak I saw, and likewise heard, the beak,

And utter with its voice both 'I' and 'My,'

When in conception it was 'We' and 'Our.'

And it began: "Being just and merciful

Am I exalted here unto that glory

Which cannot be exceeded by desire;

And upon Earth I left my memory

Such, that the evil-minded people there

Commend it, but continue not the story."

So doth a single heat from many embers

Make itself felt, even as from many loves

Issued a single sound from out that image.

Whence I thereafter: "O perpetual flowers

Of the eternal joy, that only one

Make me perceive your odors manifold,

Exhaling, break within me the great fast

Which a long season has in hunger held me,

Not finding for it any food on Earth.

Well do I know, that if in heaven its mirror

Justice Divine another realm doth make,

Yours apprehends it not through any veil.

You know how I attentively address me

To listen; and you know what is the doubt

That is in me so very old a fast."

Even as a falcon, issuing from his hood,

Doth move his head, and with his wings applaud him,

Showing desire, and making himself fine,

Saw I become that standard, which of lauds

Was interwoven of the grace divine,

With such songs as he knows who there rejoices.

Then it began: "He who a compass turned

On the world's outer verge, and who within it

Devised so much occult and manifest,

Could not the impress of his power so make

On all the universe, as that his Word

Should not remain in infinite excess.

And this makes certain that the first proud being,

Who was the paragon of every creature,

By not awaiting light fell immature.

And hence appears it, that each minor nature

Is scant receptacle unto that good

Which has no end, and by itself is measured.

In consequence our vision, which perforce

Must be some ray of that intelligence

With which all things whatever are replete,

Cannot in its own nature be so potent,

That it shall not its origin discern

Far beyond that which is apparent to it.

Therefore into the justice sempiternal

The power of vision that your world receives,

As eye into the ocean, penetrates;

Which, though it see the bottom near the shore,

Upon the deep perceives it not, and yet

'Tis there, but it is hidden by the depth.

There is no light but comes from the serene

That never is o'ercast, nay, it is darkness

Or shadow of the flesh, or else its poison.

Amply to thee is opened now the cavern

Which has concealed from thee the living justice

Of which thou mad'st such frequent questioning.

For saidst thou: 'Born a man is on the shore

Of Indus, and is none who there can speak

Of Christ, nor who can read, nor who can write;

And all his inclinations and his actions

Are good, so far as human reason sees,

Without a sin in life or in discourse:

He dieth unbaptised and without faith;

Where is this justice that condemneth him?

Where is his fault, if he do not believe?'[1]

Now who art thou, that on the bench wouldst sit

In judgment at a thousand miles away,

With the short vision of a single span?

Truly to him who with me subtilizes,

If so the Scripture were not over you,

For doubting there were marvelous occasion.

O animals terrene, O stolid minds,

The primal will, that in itself is good,

Ne'er from itself, the Good Supreme, has moved.

So much is just as is accordant with it;

No good created draws it to itself,

But it, by raying forth, occasions that."

Even as above her nest goes circling round

The stork when she has fed her little ones,

And he who has been fed looks up at her,

So lifted I my brows, and even such

Became the blessed image, which its wings

Was moving, by so many counsels urged.

Circling around it sang, and said: "As are

My notes to thee, who dost not comprehend them,

Such is the eternal judgment to you mortals."

Those lucent splendors of the Holy Spirit

Grew quiet then, but still within the standard

That made the Romans reverend to the world.

It recommenced: "Unto this kingdom never

Ascended one who had not faith in Christ,

Before or since he to the tree was nailed.

But look thou, many crying are, 'Christ, Christ!'

Who at the judgment shall be far less near

To him than some shall be who knew not Christ.

Such Christians shall the Ethiop condemn,

When the two companies shall be divided,

The one for ever rich, the other poor.

What to your kings may not the Persians say,

When they that volume opened shall behold

In which are written down all their dispraises?

There shall be seen, among the deeds of Albert,

That which ere long shall set the pen in motion,

For which the realm of Prague shall be deserted.[2]

There shall be seen the woe that on the Seine

He brings by falsifying of the coin,

Who by the blow of a wild boar shall die.

There shall be seen the pride that causes thirst,

Which makes the Scot and Englishman so mad

That they within their boundaries cannot rest;

Be seen the luxury and effeminate life

Of him of Spain, and the Bohemian,

Who valor never knew and never wished;

Be seen the Cripple of Jerusalem,

His goodness represented by an I,

While the reverse an M shall represent;

Be seen the avarice and poltroonery

Of him who guards the Island of the Fire,

Wherein Anchises finished his long life;[3]

And to declare how pitiful he is

Shall be his record in contracted letters

Which shall make note of much in little space.

And shall appear to each one the foul deeds

Of uncle and of brother who a nation

So famous have dishonored, and two crowns.

And he of Portugal and he of Norway

Shall there be known, and he of Rascia too,

Who saw in evil hour the coin of Venice.[4]

O happy Hungary, if she let herself

Be wronged no farther! and Navarre the happy,

If with the hills that gird her she be armed![5]

And each one may believe that now, as hansel

Thereof, do Nicosia and Famagosta

Lament and rage because of their own beast,[6]

Who from the others' flank departeth not."

Footnotes

1. The souls form the imperial eagle of divine justice, speaking with one voice of God's justice. Dante uses this opportune moment in front of the eagle to ask about the accessibility of Heaven to people who were born before Christ or lived in an area where Christianity was not taught. Dante starts his question by positing such a person.

2. Albert I of Habsburg (1255–1308 AD) was a Duke of Austria and Styria from 1282 and King of Germany from 1298 until his assassination. He was the eldest son of King Rudolf I of Germany and his first wife Gertrude of Hohenberg. Sometimes referred to as 'Albert the One-eyed' because of a battle injury that left him with a hollow eye socket and a permanent snarl.

From 1273 Albert ruled as a landgrave over his father's Swabian (Austrian) possessions in Alsace. In 1282 his father, the first German monarch from the House of Habsburg, invested him and his younger brother Rudolf II with the duchies of Austria and Styria, which he had seized from late King Ottokar II of Bohemia and defended in the 1278 Battle on the Marchfeld. By the 1283 Treaty of Rheinfelden his father entrusted Albert with their sole government, while Rudolf II ought to be compensated by the Further Austrian Habsburg home territories—which, however, never happened until his death in 1290. Albert and his Swabian ministeriales appear to have ruled the Austrian and Styrian duchies with conspicuous success, overcoming the resistance by local nobles.

3. After the defeat of Troy in the Trojan War, the elderly Anchises was carried from the burning city by his son Aeneas, accompanied by Aeneas' wife Creusa, who died in the escape attempt, and small son Ascanius. The subject is depicted in several paintings, including a famous version by Federico Barocci in the Galleria Borghese in Rome. Anchises himself died and was buried in Sicily many years later. Aeneas later visited Hades and saw his father again in the Elysian Fields.

4. "he of Portugal" refers to King John I of Portugal; "he of Norway" refers to King Haakon V of Norway; and "he of Rascia" refers to Henry of Rascia.

John I (1357–1433 AD), also called John of Aviz, was King of Portugal from 1385 until his death in 1433. He is recognized chiefly for his role in Portugal's victory in a succession war with Castile, preserving his country's independence and establishing the Aviz dynasty on the Portuguese throne. His long reign of 48 years, the most extensive of all Portuguese monarchs, saw the beginning of Portugal's overseas expansion. John's well-remembered reign in his country earned him the epithet of Fond Memory (de Boa Memória).

Haakon V Magnusson (1270–1319 AD) was King of Norway from 1299 until 1319.

Haakon was the younger surviving son of Magnus the Lawmender, King of Norway, and his wife Ingeborg of Denmark. Through his mother, he was a descendant of Eric IV, king of Denmark. In 1273, his elder brother, Eirik, was named junior king under the reign of their father, King Magnus. At the same time, Haakon was given the title "Duke of Norway", and from his father's death in 1280, ruled a large area around Oslo in Eastern Norway and Stavanger in the southwest, subordinate to King Eirik. Haakon succeeded to the royal throne when his older brother died without sons.

Henry of Rascia, also known as Henry of Hungary, was an historical figure who ruled parts of Italy during the late 12th century. Dante mentions him in this canto as a king who was known for his poor governance and the negative impact he had on the region. His mention serves as an illustration of the consequences of failed leadership and moral corruption.

Henry's rule was characterized by strife and conflict, and Dante criticizes him for not properly caring for his subjects and for allowing discord to flourish. This serves to underscore one of Dante's central themes: the importance of virtuous leadership in the moral order of society.

The Grand Principality of Serbia, also known by the anachronistic exonym Rascia, was a medieval Serbian state that existed from the second half of the 11th century up until 1217, when it was transformed into the Kingdom of Serbia. After the Grand Principality of Serbia emerged, it gradually expanded during the 12th century, encompassing various neighboring regions, including territories of Raška, modern Montenegro, Herzegovina, and southern Dalmatia. It was founded by Grand Prince Vukan, who initially served as the regional governor of the principality, appointed by King Constantine Bodin. During the Byzantine–Serbian wars (1090), Vukan gained prominence and became a self-governing ruler in the inner Serbian regions. He founded the Vukanović dynasty, which ruled the grand principality. Through diplomatic ties with the Kingdom of Hungary, Vukan's successors managed to retain their self-governance, while also recognizing the supreme over-lordship of the Byzantine Empire, up to 1180. Grand Prince Stefan Nemanja gain ed full independence and united almost all Serbian lands. His son, Grand Prince Stefan was crowned King of Serbia in 1217, while his younger son Saint Sava became the first Archbishop of Serbs, in 1219.

5. Philip IV (1268–1314 AD), called Philip the Fair, was King of France from 1285 to 1314. By virtue of his marriage with Joan I of Navarre, he was also King of Navarre and Count of Champagne as Philip I from 1284 to 1305. Although Philip was known to be hand some, hence the epithet le Bel, his rigid, autocratic, imposing, and inflexible personality gained him other nicknames, such as the Iron King. His fierce opponent Bernard Saisset, bishop of Pamiers, said of him: "He is neither man nor beast. He is a statue. "

Philip, seeking to reduce the wealth and power of the nobility and clergy, relied instead on skillful civil servants, such as Guillaume de Nogaret and Enguerrand de Marigny, to govern the kingdom. The king, who sought an uncontested monarchy, compelled his vassals by wars and restricted their feudal privileges, paving the way for the transformation of France from a feudal country to a centralized early modern state. Internationally, Philip's ambitions made him highly influential in European affairs, and for mu ch of his reign, he sought to place his relatives on foreign thrones. Princes from his house ruled in Hungary and in the Kingdom of Naples, and he tried and failed to make another relative the Holy Roman Emperor.

6. Nicosia, also known as Lefkosia or Lefkoşa, is the capital of Cyprus, which is geographically located in Asia. It is the southeastern-most of all European Union member states' capital cities.

Famagusta is a city located in the Famagusta District of the same name on the eastern coast of Cyprus, currently controlled by the de facto republic of Northern Cyprus. It is located east of the capital, Nicosia, and possesses the deepest harbor of the island. During the Middle Ages Famagusta was the island's most important port city and a gateway to trade with the ports of the Levant, from where the Silk Road merchants carried their goods to Western Europe.

In interweaving this unpleasant image throughout the last quarter of the canto, Dante underscores the insidiousness of bad rulership. The injustice of kings and princes, he seems to argue, spreads throughout the world like an unseen but devastating plague with running sores. Thus—as so often in the Divine Comedy—Dante insinuates corruption and decay are the norm in contemporary politics, as contrasted with a bygone age of justice and equanimity. This intricate and carefully plotted word play constructed f rom repeated letters gives a sense of the pleasures of language and symbol Dante employed as part of his medieval education, when learning in Latin was greatly valued. He uses the word play to make a political point even stronger than mere criticism might h ave it, bringing the old-fashioned construct into the modern world of 1300 in order to damn the most forcefully those who were endangering the future of mankind and faith, as he saw it.

Illustrations of Paradiso

Appeared before me with its wings outspread / The beautiful image that in sweet fruition / Made jubilant the interwoven souls; Par. XIX, lines 1-3

Beatrice

Top of page