Dante's Divine Comedy: Paradiso

Canto XVIII

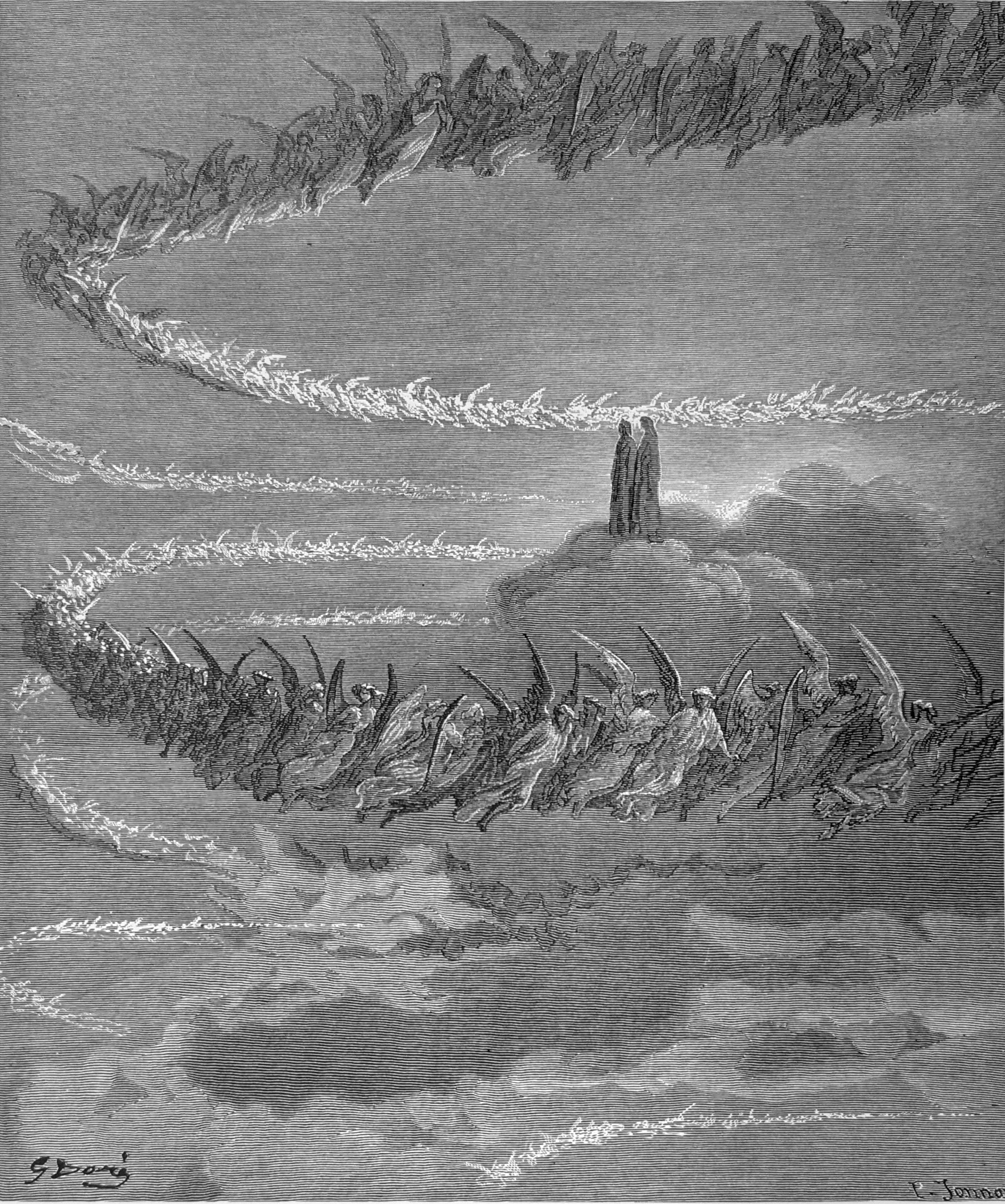

As Beatrice consoles Dante, Cacciaguida calls out the names of eight warrior saints and joins them as they flash along the pattern of the Cross. Dante, and the ever-more-beautiful Beatrice, ascend to Jupiter, the Sixth Heaven. As the planet's silvery sheen replaces the ruddy glow of Mars, Dante beholds a spectacular display of lit-up letters (the souls of the Just) spelling out "Diligite justitiam qui judicatis terram" (Love justice, ye that judge on Earth). The final 'm' reconfigures into the imperial eagle, symbol of justice. Dante accuses the Pope of abusing his holy office.[1]

Now was alone rejoicing in its word

That soul beatified, and I was tasting

My own, the bitter tempering with the sweet,

And the Lady who to God was leading me

Said: "Change thy thought; consider that I am

Near unto Him who every wrong disburdens."

Unto the loving accents of my comfort

I turned me round, and then what love I saw

Within those holy eyes I here relinquish;

Not only that my language I distrust,

But that my mind cannot return so far

Above itself, unless another guide it.

Thus much upon that point can I repeat,

That, her again beholding, my affection

From every other longing was released.

While the eternal pleasure, which direct

Rayed upon Beatrice, from her fair face

Contented me with its reflected aspect,[2]

Conquering me with the radiance of a smile,

She said to me, "Turn thee about and listen;

Not in mine eyes alone is Paradise."

Even as sometimes here do we behold

The affection in the look, if it be such

That all the soul is wrapt away by it,

So, by the flaming of the effulgence holy

To which I turned, I recognized therein

The wish of speaking to me somewhat farther.

And it began: "In this fifth resting-place

Upon the tree that liveth by its summit,

And aye bears fruit, and never loses leaf,

Are blessed spirits that below, ere yet

They came to Heaven, were of such great renown

That every Muse therewith would affluent be.

Therefore look thou upon the cross's horns;

He whom I now shall name will there enact

What doth within a cloud its own swift fire."

I saw athwart the Cross a splendor drawn

By naming Joshua, (even as he did it,)

Nor noted I the word before the deed;[3]

And at the name of the great Maccabee

I saw another move itself revolving,

And gladness was the whip unto that top.[4]

Likewise for Charlemagne and for Orlando,

Two of them my regard attentive followed

As followeth the eye its falcon flying.[5]

William thereafterward, and Renouard,

And the Duke Godfrey, did attract my sight

Along upon that Cross, and Robert Guiscard.[6]

Then, moved and mingled with the other lights,

The soul that had addressed me showed how great

An artist 'twas among the heavenly singers.

To my right side I turned myself around,

My duty to behold in Beatrice

Either by words or gesture signified;

And so translucent I beheld her eyes,

So full of pleasure, that her countenance

Surpassed its other and its latest wont.

And as, by feeling greater delectation,

A man in doing good from day to day

Becomes aware his virtue is increasing,

So I became aware that my gyration

With heaven together had increased its arc,

That miracle beholding more adorned.

And such as is the change, in little lapse

Of time, in a pale woman, when her face

Is from the load of bashfulness unladen,

Such was it in mine eyes, when I had turned,

Caused by the whiteness of the temperate star,

The sixth, which to itself had gathered me.[7]

Within that Jovial torch did I behold

The sparkling of the love which was therein

Delineate our language to mine eyes.

And even as birds uprisen from the shore,

As in congratulation o'er their food,

Make squadrons of themselves, now round, now long,

So from within those lights the holy creatures

Sang flying to and fro, and in their figures

Made of themselves now D, now I, now L.[8]

First singing they to their own music moved;

Then one becoming of these characters,

A little while they rested and were silent.

O divine Pegasea, thou who genius

Dost glorious make, and render it long-lived,

And this through thee the cities and the kingdoms,[9]

Illume me with thyself, that I may bring

Their figures out as I have them conceived!

Apparent be thy power in these brief verses!

Themselves then they displayed in five times seven

Vowels and consonants; and I observed

The parts as they seemed spoken unto me.

'Diligite justitiam,' these were

First verb and noun of all that was depicted;

'Qui judicatis terram' were the last.[10]

Thereafter in the M of the fifth word

Remained they so arranged, that Jupiter

Seemed to be silver there with gold inlaid.

And other lights I saw descend where was

The summit of the M, and pause there singing

The good, I think, that draws them to itself.

Then, as in striking upon burning logs

Upward there fly innumerable sparks,

Whence fools are wont to look for auguries,[11]

More than a thousand lights seemed thence to rise,

And to ascend, some more, and others less,

Even as the Sun that lights them had allotted;

And, each one being quiet in its place,

The head and neck beheld I of an eagle

Delineated by that inlaid fire.

He who there paints has none to be his guide;

But Himself guides; and is from Him remembered

That virtue which is form unto the nest.

The other beatitude, that contented seemed

At first to bloom a lily on the M,

By a slight motion followed out the imprint.

O gentle star! what and how many gems

Did demonstrate to me, that all our justice

Effect is of that heaven which thou ingemmest!

Wherefore I pray the Mind, in which begin

Thy motion and thy virtue, to regard

Whence comes the smoke that vitiates thy rays;

So that a second time it now be wroth

With buying and with selling in the temple

Whose walls were built with signs and martyrdoms!

O soldiery of heaven, whom I contemplate,

Implore for those who are upon the Earth

All gone astray after the bad example!

Once 'twas the custom to make war with swords;

But now 'tis made by taking here and there

The bread the pitying Father shuts from none.

Yet thou, who writest but to cancel, think

That Peter and that Paul, who for this vineyard

Which thou art spoiling died, are still alive!

Well canst thou say: "So steadfast my desire

Is unto him who willed to live alone,

And for a dance was led to martyrdom,

That I know not the Fisherman nor Paul."

Footnotes

1. Dante's time in the sphere of Mars ends with another "roll call" of exemplarily virtuous lives. The logic of who belongs in Heaven versus Limbo is getting a little fuzzy at this point, as neither Joshua nor Judas Maccabeus lived during the time of Christ. T he exact criteria for salvation are, however, less important to this canto than are Dante's efforts to elaborate the virtue of courage in this realm of Jupiter. To the crusaders of previous cantos he adds Hebrews, an ancient military leader, Joshua, a warrior-priest, Judas Maccabeus, an emperor, Charlemagne, and a medieval paladin Orlando (Roland). Chronologically, Dante's examples stretch across two and a half millennia; geographically, they reach from the Levant, the eastern Mediterranean countries, to southwestern Europe. This is, by medieval literary standards, a truly cosmopolitan group of heroes.

Present in this sphere are David, Hezekiah, Constantine, William II of Sicily, as well as two pagans: Trajan, who was converted to Christianity according to a medieval legend, and Ripheus the Trojan, who was saved by the mercy of God in an act of predestination.

The planet Jupiter is traditionally associated with the king of the gods, so Dante makes this planet the home of the rulers who displayed justice.

2. Beatrice "Bice" di Folco Portinari (1265–1290) was an Italian woman who has been commonly identified as the principal inspiration for Dante Alighieri's Vita Nuova, and is also identified with the Beatrice who acts as his guide in the last book of his narrative poem the Divine Comedy (La Divina Commedia), Paradiso, and during the conclusion of the preceding Purgatorio. In the Comedy, Beatrice symbolizes divine grace and theology.

3. Joshua, also known as Yehoshua, Jehoshua, or Josue, was Moses' assistant in the books of Exodus and Numbers, and later succeeded Moses as leader of the Israelite tribes in the Book of Joshua of the Hebrew Bible. His name was Hoshea, the son of Nun, of the tribe of Ephraim, but Moses called him "Yehoshua". According to the Bible, he was born in Egypt prior to the Exodus.

In Numbers 13:1, the Hebrew Bible identifies Joshua as one of the twelve spies of Israel sent by Moses to explore the land of Canaan. After the death of Moses, he led the Israelite tribes in the conquest of Canaan, and allocated lands to the tribes. According to biblical chronology, Joshua lived some time in the Bronze Age. According to Joshua 24:29 Joshua died at the age of 110.

4. Judas Maccabaeus or Maccabeus (died 160 AD), also known as Judah Maccabee, was a Jewish priest and a son of the priest Mattathias. He was an early leader in the Maccabean Revolt against the Seleucid Empire, taking over from his father around 166 BC, and leading the revolt until his death in 160 BC.

The Jewish holiday of Hanukkah ("Dedication") commemorates the restoration of Jewish worship at the Second Temple in Jerusalem in 164 BC after Judah Maccabee removed all of the statues depicting Greek gods and goddesses and purified it.

5. Charlemagne (748–814 AD) was King of the Franks from 768, King of the Lombards from 774, and Emperor of what is now known as the Carolingian Empire from 800. He united most of Western and Central Europe and was the first recognized emperor to rule from the west after the fall of the Western Roman Empire approximately three centuries earlier. Charlemagne's reign was marked by political and social changes that had lasting influence on Europe throughout the Middle Ages.

Roland, also called Orlando or Rolando (died 778 AD) was a Frankish military leader under Charlemagne who became an epic hero and one of the principal figures in the literary cycle known as the Matter of France. The historical Roland was military govern or of the Breton March, responsible for defending Francia's frontier against the Bretons. His only historical attestation is in Einhard's Vita Karoli Magni, which notes he was part of the Frankish rearguard killed in retribution by the Basques in Iberia a t the Battle of Roncevaux Pass.

6. William the Conqueror (1028–1087 AD), sometimes called William the Bastard, was the first Norman king of England (as William I), reigning from 1066 until his death. A descendant of Rollo, he was Duke of Normandy (as William II) from 1035 onward. By 1060 , following a long struggle, his hold on Normandy was secure. In 1066, following the death of Edward the Confessor, William invaded England, leading a Franco-Norman army to victory over the Anglo-Saxon forces of Harold Godwinson at the Battle of Hastings, and suppressed subsequent English revolts in what has become known as the Norman Conquest. The rest of his life was marked by struggles to consolidate his hold over England and his continental lands, and by difficulties with his eldest son, Robert Curthose.

Renouard is an historical figure who is recognized as a noble warrior and one of the souls in Heaven. He is associated with the legendary exploits of Charlemagne and is celebrated for his valor in battle. Renouard's role serves to illustrate the connect ion between earthly actions and their heavenly consequences, reinforcing the poem's overarching themes of justice and divine order.

Godfrey III (997–1069 AD), called the Bearded, was the eldest son of Gothelo I, Duke of Upper and Lower Lorraine. By inheritance, Godfrey was Count of Verdun and he became Margrave of Antwerp as a vassal of the Duke of Lower Lorraine. The Holy Roman Emperor Henry III authorized him to succeed his father as Duke of Upper Lorraine in 1044, but refused him the ducal title in Lower Lorraine, for he feared the power of a united duchy. Instead, Henry threatened to appoint his younger brother, Gothelo, as Duke i n Lower Lorraine. At a much later date, Godfrey became Duke of Lower Lorraine, but he had lost the upper duchy by that point in time.

Robert Guiscard (1015–1085 AD), also referred to as Robert de Hauteville, was a Norman adventurer remembered for his conquest of southern Italy and Sicily in the 11th century. Robert was born into the Hauteville family in Normandy, the sixth son of Tancred de Hauteville and his wife Fressenda. He inherited the County of Apulia and Calabria from his brother in 1057, and in 1059 he was made Duke of Apulia and Calabria and Lord of S icily by Pope Nicholas II. He was also briefly Prince of Benevento (1078–1081), before returning the title to the papacy.

7. Jupiter, in this case, a wandering star distinct from the fixed stars. This is the sixth sphere of heaven. On Jupiter, as previously in the spheres of Mars and the sun, the souls form a shape that underscores their distinctive virtue. Jupiter is the sphere of justice, populated mainly by rulers known for their fairness and composure. For Dante, the paragon of earthly justice must be Rome—specifically, the Roman Empire, which is traditionally symbolized by an eagle. In Purgatory 32 Dante used eagle imagery to connote the rise of the Empire and its role in establishing, and then corrupting, the Church. Here, he seems to revisit Rome in a more uniformly positive light, as the archetype of just rulership.

The limitations of Dante's astronomy also become a little clearer in this canto. He imagines Jupiter not as the now-familiar whorled and spotted giant planet, but as a silvery, starlike body. The telescope would not be invented until three centuries after D ante's lifetime, and details such as the Great Red Spot would first be observed only in the late 17th century. Perhaps this is just as well, since a "temperate," evenly colored star fits well with Dante's image of justice—better, anyway, than the roiling, planet-sized storm we now know Jupiter to be. There will be more to say about Dante's astronomical views in later cantos, as his theories on the very structure of the solar system become clear.

8. The holy creatures represented by the letters D, I, and L are angels or blessed souls that form patterns in the sky as they sing. These letters symbolize divine concepts, with D representing Diligite iustitiam, "Love Justice" and I and L likely representing other virtues or messages related to divine justice and order.

9. Pegasus is a winged horse in Greek mythology, usually depicted as a white stallion. He was sired by Poseidon, in his role as horse-god, and foaled by the Gorgon Medusa. Pegasus was the brother of Chrysaor, both born from Medusa's blood when their mother was decapitated by Perseus. Greco-Roman poets wrote about his ascent to heaven after his birth and his obeisance to Zeus, who instructed him to bring lightning and thunder from Olympus.

Pegasus is the creator of Hippocrene, the fountain on Mount Helicon. He was captured by the Greek hero Bellerophon, near the fountain Peirene, with the help of Athena and Poseidon. Pegasus allowed Bellerophon to ride him in order to defeat the monster Chimera, which led to many more exploits. Bellerophon later fell from Pegasus's back while trying to reach Mount Olympus. Both Pegasus and Bellerophon were said to have died at the hands of Zeus for trying to reach Olympus. Other tales have Zeus bring Pegasus to Olympus to carry his thunderbolts.

Pegasus is a constellation in the northern sky, named after the winged horse Pegasus in Greek mythology. It was one of the 48 constellations listed by the 2nd-century astronomer Ptolemy, and is one of the 88 constellations recognized today.

10. Diligite justitiam, "Love justice", noted by " D".

Qui judicatis terram, "You who judge the earth", perhaps noted by "I", the Roman letter for justice?

11. augurium, Latin, meaning divination, prediction, omen, portent, or foreboding. augury with three definitions: (a) A divination based on the appearance and behavior of animals; (b) An omen or prediction; a foreboding; a prophecy; or (c) An event that is experienced as indicating important things to come.

Illustrations of Paradiso

The holy creatures / Sang flying to and fro, Par. XVIII, lines 76-77

O soldiery of heaven, whom I contemplate, / Implore for those who are upon the Earth / All gone astray after the bad example! Par. XVIII, lines 124-126

Top of page