Red vs Blue, 50 Years of Red Flag

by Connor Madison

Sport Aviation, September 2025, pp 54-64.

In April 2025 at Nellis Air Force Base outside Las Vegas, Nevada, the United States Air Force held a ceremony celebrating 50 years of its aerial combat exercise Red Flag. Several current and former Red Flag personnel were in attendance for the ceremony including Col. Eric Winterbottom, commander of the 414th Combat Training Squadron, the unit responsible for putting on the Red Flag exercises.

Winterbottom spoke at the ceremony and pointed out that it was more than just an anniversary, but evidence of how well the program has developed tactics for its aviators to successfully take those lessons into combat. It was also pointed out during the ceremony that 50 years ago the Air Force decided to make a change to ensure the losses that occurred during the Vietnam War didn’t happen again. That resulted in the creation of Red Flag.

Origin Story

Red Flag was born out of the lessons learned from Vietnam. In short, USAF aircrews had a difficult time fighting the North Vietnamese, which resulted in much higher losses than expected. Of course, this alarmed Air Force leadership. If they couldn’t beat a Soviet-equipped air force using Soviet tactics, how would they fare against the Soviets themselves?

Subsequently, the Air Force went about finding out what had gone wrong and where improvements could be made. The resulting reports brought forth several important takeaways.

The first takeaway was the aircrews had little to no experience dogfighting against dissimilar aircraft. One of the first solutions for this was the creation of the 64th and 65th Aggressor Squadrons in 1972. These squadrons were equipped with the Northrop F-5, and their pilots trained in Soviet air combat tactics. Their job was to then travel from squadron to squadron and train fighter pilots how to fight against a smaller aircraft using Soviet tactics.

While this was a good start, Air Force personnel knew they had to take it further. Another finding among the reports was that air- crews were found to have a 90 percent survival rate for their combat tour once they made it past their first 10 missions.

Lt. Col. Richard “Moody” Suter was the one to put forth the idea of the Air Force having dedicated exercises where aviators would be able to complete those 10 missions in a

controlled and safe environment. The idea was so well received that the first Red Flag took place in November 1975 at Nellis Air Force Base in Las Vegas, Nevada. This was just four months after Suter had come forward with his plan.

Air Force historian Brian D. Laslie said the initial Red Flag design “was to combine good basic fighter skills with realistic threat employment.” The first exercise, “Red Flag I,” in November 1975 saw participation from an F-4 unit as well as F-105s, OV-10s, and CH-53s. The next two exercises continued to grow in size with the third having almost 1,000 sorties flown through the duration.

The pilots who flew in the initial Red Flags were incredibly positive about their experiences, which only further spurred more growth into the 1980s. The evolving technology meant the exercises themselves became more advanced. With the advancements, it also grew closer to what real combat would be like, which, in turn, was more difficult for the participants.

The 1980s also saw the introduction of the United States’ foreign allied air forces taking part in Red Flag exercises. To date, 29 different countries have participated. The success of the exercise is evident in that it’s lasted for 50 years and shows no signs of stopping.

It’s estimated that more than 30,000 aircraft and 530,000 military personnel have taken part in Red Flags over its 50-year history.

The Hosts

Red Flag today has grown to be a large-scale operation, and the 414th Combat Training Squadron at Nellis is responsible for its planning and execution. Currently, it hosts three exercises a year. The first includes the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. The second is made up of coalition forces and varies depending on what nations want to participate. The final Red Flag of the year is United States only, with joint force participation.

The team that puts on Red Flag is a mix of military and civilian contractors, and many of the civilians are former military who were with the 414th, which shows how much they believe in the mission.

“The 414th is what we call the White force,” Winterbottom said. “We bring together the Blue force—the good guys, our main participants in our training audience—to fight the Red force, which is very heavily our professional aggressors here at Nellis. We, as the White force, basically run the operation. We like to say that we build the sandbox for Blue force to play in.”

Running the operation means the 414th facilitates all of the logistics necessary to put on a large-scale exercise like Red Flag.

On the surface, without visiting Nellis it can be hard to picture how much goes into the planning, hosting, and execution of a Red Flag. Each of the three Red Flags hosted during the year requires roughly a nine-month planning process. So, while one Flag is taking place, planning is going on for the next two.

For one of those single Flags, it’s {not un}common for there to be 3,000 people visiting Nellis to participate in the event. This obviously requires support from many different departments. For starters, the Nellis Support Center is responsible for making sure those 3,000 people are housed and have ground transportation.

The 414th maintenance personnel are another of the departments and are undoubtedly among the unsung heroes of the operation. They facilitate 100-plus aircraft visiting a remote air base. Their job is to make sure those visitors have everything they need to be successful. This also includes providing ordnance for units that don’t normally have it, as they may not have a nearby bombing range like Nellis.

The personnel who make up the maintenance team come from diverse backgrounds, working on both fourth- and fifth-generation aircraft, and this sets them up to be successful in hosting a wide variety of aircraft that are typical of most Red Flags. When it comes time to fly during the operation, another host of personnel based at Nellis are involved. The obvious ones are the people who make up the Red force, which include flying aggressors, surface-to-air aggressors, and information aggressors. Then there’s the

operational support squadron that manages the airfield and the airspace so that everyone can get safely to and from the fight.

The Sandbox

Another huge piece of Red Flag is the Nevada Test and Training Range (NTTR) where the actual fighting takes place. Located north of the base, the NTTR is a 12,000-square-mile area and is one of the primary reasons Nellis was chosen as the host for Red Flag. The range features stationary targets that can be bombed, along with the deployment of moving targets that allow for dynamic targeting activities. Exercises will often put people on the ground in the range to practice survival tactics in the event they need to bail out of their aircraft in combat.

The NTTR also features 30-plus legacy systems that are capable of simulating almost any ground threat imaginable, as well as cyber- and space-based threats.

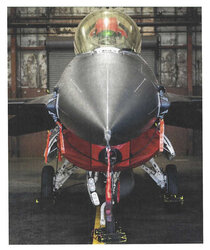

Another key piece of the NTTR and Red Flag is that it’s an instrumented range. This means fourth-generation aircraft, like the F-16, will carry Air Combat Maneuvering Instrumentation Pods, and the instruments on the range are then able to provide real-time locations of the aircraft

during a given fight. Fifth-generation fighters like the F-35 have the capability built in so they don’t have to carry the pods.

The ability to see the fight unfold in real time greatly aids those who are responsible for refereeing the fight. It’s also a vital tool in debriefing what happened during the fight.

The Fight Is On

The average Red Flag will take place for two weeks and usually features two sorties per day. The sorties are referred to as “vuls,” which stands for vulnerability window—the time of maximum exposure and danger during a fight.

Before flying a vul, both the Blue and Red forces will have mass briefings on what the objective of the mission will be followed by smaller formation specific briefings. When it comes to the actual flying of a vul, it’s easy to picture it as just fighter aircraft dogfighting with each other. While that certainly is one aspect of the operation, just about every type of aircraft in U.S. and allied nation inventory has participated in a Red Flag.

This includes tankers like the KC-135 and KC-46. All three of the United States’ current strategic bombers have participated: the B-1, B-2, and B-52. AWACS (airborne warning and control system) aircraft like the E-3 Sentry and Australian E-7 Wedgetail are key players in a lot of vuls.

Electronic counter-measure aircraft, like the Navy’s EA-18 Growler and the Air Force’s RC-135 reconnaissance platforms, are also common participants. The integration between the different types of aircraft are crucial to the training being as realistic as possible.

The word integration itself is mentioned a lot around the Red Flag operation, which extends beyond just the different aircraft working together.

“Integration is key,” said Winterbottom. “At home station, our warfighters don’t get to interact with the full spectrum of capability that our joint and multinational force brings together. We try to drive that integration here at Red Flag. In addition to all of those air operations, we also have cyber operations going on, both defensive and offensive cyber, along with nonkinetic effects, which is very heavily the Space Force bringing in their abilities.”

The integration across the board of the whole operation is really one of the things that stands out and shows just how intense and impactful the training is that Red Flag provides.

Another aspect of the actual fighting that is worth mentioning is that none of the air-to-air fighting involves live firing. As previously mentioned, the instruments on the NTTR provide real-time data of all the aircraft locations.

The White force then uses what it calls RTOs (range training officers) who manage the fight by looking at each

“shot” taken by both sides of the fight. They assess the effectiveness of a shot and then communicate whether the pilot is “dead.” If that’s the case, the pilot then has to fly to a designated regeneration area before rejoining the fight.

Red Force

The 64th Aggressor Squadron is one of two aircraft aggressor squadrons based at Nellis that are responsible for flying as the enemy Red force during Red Flag exercises. As previously noted, the 64th was established in 1972, three years before the Red Flag exercises began. The squadron has since been one of the squadrons responsible for providing a professional aggressor force.

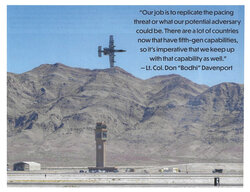

“The role of the 64th, in general, is to provide adversarial support to train our forces to go to war tomorrow,” said Lt. Col. Don “Bodhi” Davenport, the 64th’s squadron commander. “We are requested, respected, and required adversary air that are on call to help train our forces.”

Davenport’s job as the commander is to command all aspects of the squadron.

“I have 39 people in my squadron that I supervise, mentor, and then also provide instruction as an F-16 instructor pilot,” he said.

When it comes to selecting pilots to join the 64th he mentioned that they typically look for a pilot with experience who has been on either one or two assignments. Having experience flying the F-16 and/or experience as an instructor is desired but not required.

“Once we get a hold of said individual, we’re going to put them through an aggressive qualification training course and get them on step,” Davenport said. “Typically, about 10 rides to get them to the level that we expect them to be at once we release them to be a Red force.”

The 64th currently flies the F-16C/M, a fourth-generation fighter. With the advancement of the United States’ adversaries, the need to represent fifth-generation capabilities are taken on by the 65th Aggressor Squadron, which currently flies the F-35. Part of being a successful Red force requires the two squadrons to work hand in hand.

“We train with the 65th every day,’ Davenport said. “We balance each other out with their fifth-gen and our fourth-gen capabilities to present the most realistic adversarial threat that we think we’re going to see. Our job is to replicate the pacing threat or what our potential adversary could be. There are a lot of countries now that have fifth-gen capabilities, so it’s imperative that we keep up with that capability as well, which is why we collaborate with the 65th.”

Ground Aggressors

While the aircraft portion of the Red force is what most would picture when thinking of the adversary force, they are just one portion of a larger ageressor force. As previously mentioned, part of Red Flag is integration that involves ground- and cyber-based threats. The 507th Air Defense Aggressor Squadron (ADAS), 57th Information Aggressor Squadron (IAS), and 527th Space Aggressor Squadron make up that part of the Nellis-based aggressor force (in addition to the 64th and 65th).

For the 507th ADAS, its mission is know, teach, and replicate. Essentially, its job is to make pilots more aware of what an enemy can do with a ground-based threat and how to eliminate that threat. The 507th ADAS is unique in

that it is the only unit in the United States armed forces that does what it does.

Speaking with members of the unit, they mention one of the biggest challenges they face is to keep up with the constantly evolving threats in the world and then coming up with unique ways of simulating those threats during an exercise. The equipment on the range is a snowball of old and new equipment.

Older equipment on the range is still useful to the squadron as it can be used to create signal density. The 507th team also mentioned that the difficulty for the exercises can be scaled; usually they start easy and get harder. They added that the 414th does a good job of tailoring each Red Flag to match the participants, and each Red Flag is always different. In addition, Red Flag can be used for squadrons to prove certain pilots are able to lead a strike package. In these situations, ADAS will “take the gloves off” and make the exercise extremely difficult.

During the fight, the 507th has several assessors that are responsible for assessing kills and making sure they are accurate. They use a team of five to six individuals and can determine the accuracy in roughly two minutes. The assessors also combine massive amounts of data in a matter of hours to create simplified products for the debrief after the fight. The debrief is then considered one of the most important aspects of the whole operation. It’s where they dissect what went wrong and right, and lessons are learned.

Proven in Combat

As if 50 years of continuous operation wasn’t enough proof that Red Flag is integral to the Air Force, the pilots

who flew in Desert Storm are firsthand examples of how well the training works. Dr. Brian D. Laslie makes the comparison between a dogfight in Vietnam versus a similar one that took place during Desert Storm.

The fight in Vietnam took place in April 1965 where a pair of F-4 Phantoms got into a dogfight with four MiG-17s, which resulted in a probable kill of only one MiG. In total, the Phantom crews had fired six missiles at the MiGs with only one that tracked, but it was evaded by the enemy MiG.

The Desert Storm example Laslie cites happened in January 1991. A pair of F-15s went up against a pair of MiG-25s. Once again, the U.S. aircrews fired six missiles (three AIM-9s and three AIM-7s), but this time they downed both enemy aircraft. Laslie drew the conclusion that if technology and weapons were relatively similar in both fights, there has to be another factor involved that made the U.S. crews more successful. That factor was the Red Flag training the crews had been through.

Many of the pilots who participated in Desert Storm backed up Laslie’s conclusion, saying outright that their Red Flag experiences were what made them successful in actual combat. Laslie additionally added that one of the US. pilots with a MiG kill said the main reason he was successful instead of his opponent was because he had been through hundreds of dogfights during Red Flag.

50 More Years

Winterbottom himself had previously been a Blue force participant in Red Flag when he was a lieutenant flying the F-16.

“It was exactly what we say it is,” he said. “It’s a high-intensity environment that prepares our warfighters to go off and do the real thing if necessary.”

Speaking to the importance of the experience for not just himself but all of the participants over 50 years, he agreed it’s truly an invaluable experience.

“Red Flag has endured for 50 years because it continues to evolve, to present our Blue participants with scenarios needed to prepare them for conflict.”

Davenport echoed Winterbottom’s sentiments that the continued evolution of Red Flag is key to its future.

“To be here during the 50th anniversary is super important,” he said. “It’s a great opportunity to take a look at what we’ve done the last 50 years and then look forward to the next 50 years and really refine that. I think right now is a pivotal time in our history to really hone those last 50 years and look forward [to] the next 50.”

Connor Madison, EAA 1132705, is EAA's staff photographer, capturing images of all kinds of aircraft both on the ground and in the air. When he's not shooting photos of airplanes for work, you can find him watching racing, playing guitar, and shooting photos (and building models) of airplanes for fun. Email Connor at cmadison@eaa.org.

Images

RedFig01.jpg |  RedFig02.jpg |

RedFig03.jpg |  RedFig04.jpg |

RedFig05.jpg |  RedFig06.jpg |

RedFig07.jpg |  RedFig08.jpg |

RedFig09.jpg |  RedFig10.jpg |

RedFig11.jpg |  thRedFig12.jpg |