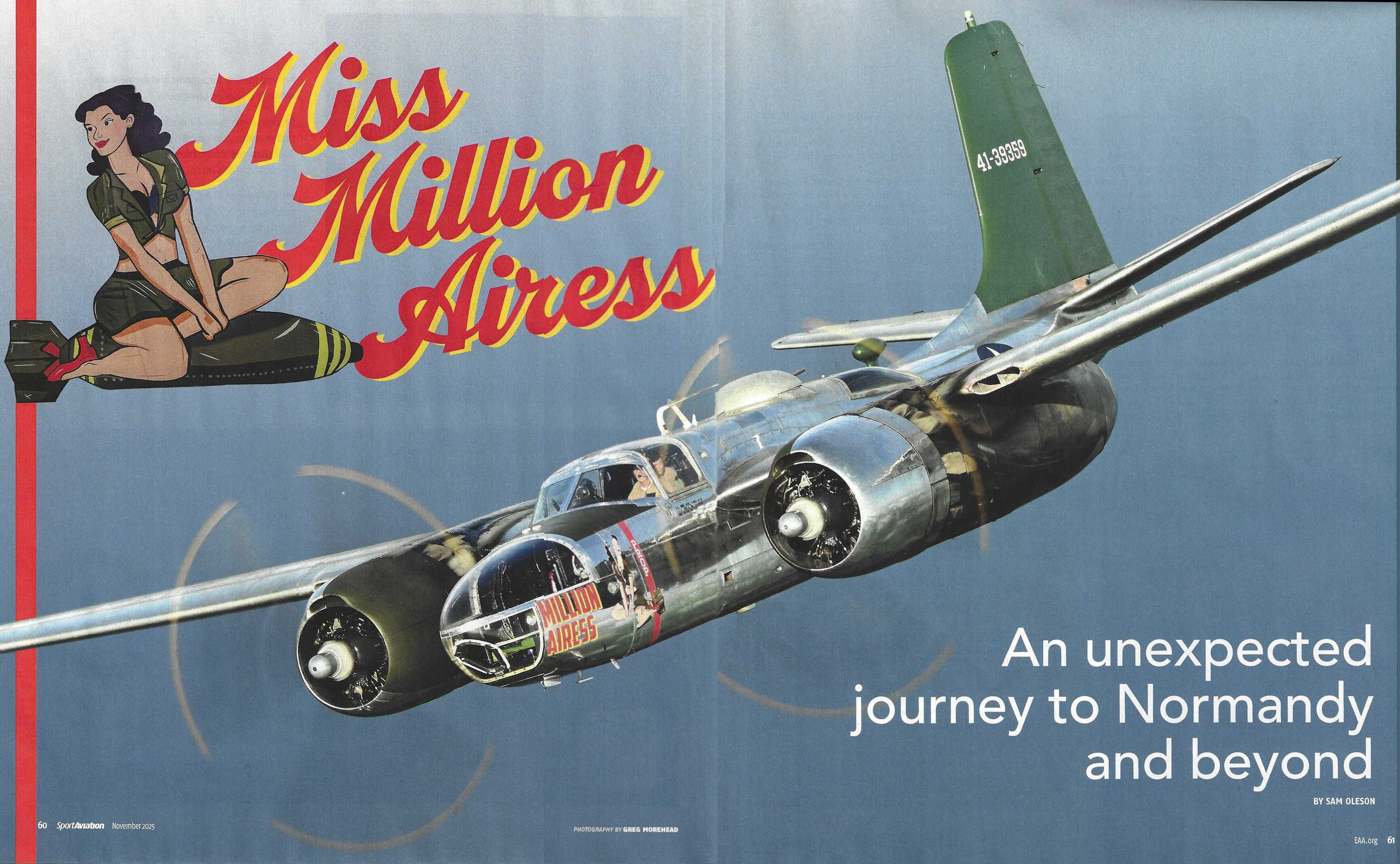

Miss Million Airess

An unexpected journey to Normandy and beyond

by Sam Oleson

Photography by Greg Morehead, et al.

Sport Aviation, November 2025, pp 60-69.

If anyone AT EAA AirVenture Oshkosh 2024 saw the A-26C Miss Million Airess parked in the Warbirds area and was curious about where it traveled to Oshkosh from, they might have looked up the N-number, N26BP, in the FAA Registry. They’d have seen it was registered and based in Houston, Texas, and maybe thought to themself, “Oh, that’s a bit of a lengthy trip to Oshkosh.” What they probably didn’t know was that Miss Million Airess did not travel to Oshkosh from Houston. No, AirVenture 2024 was simply the cherry on top of a journey that took the airplane and its crew across the Atlantic Ocean to Britain, France, Eastern Europe, and back again.

Roger

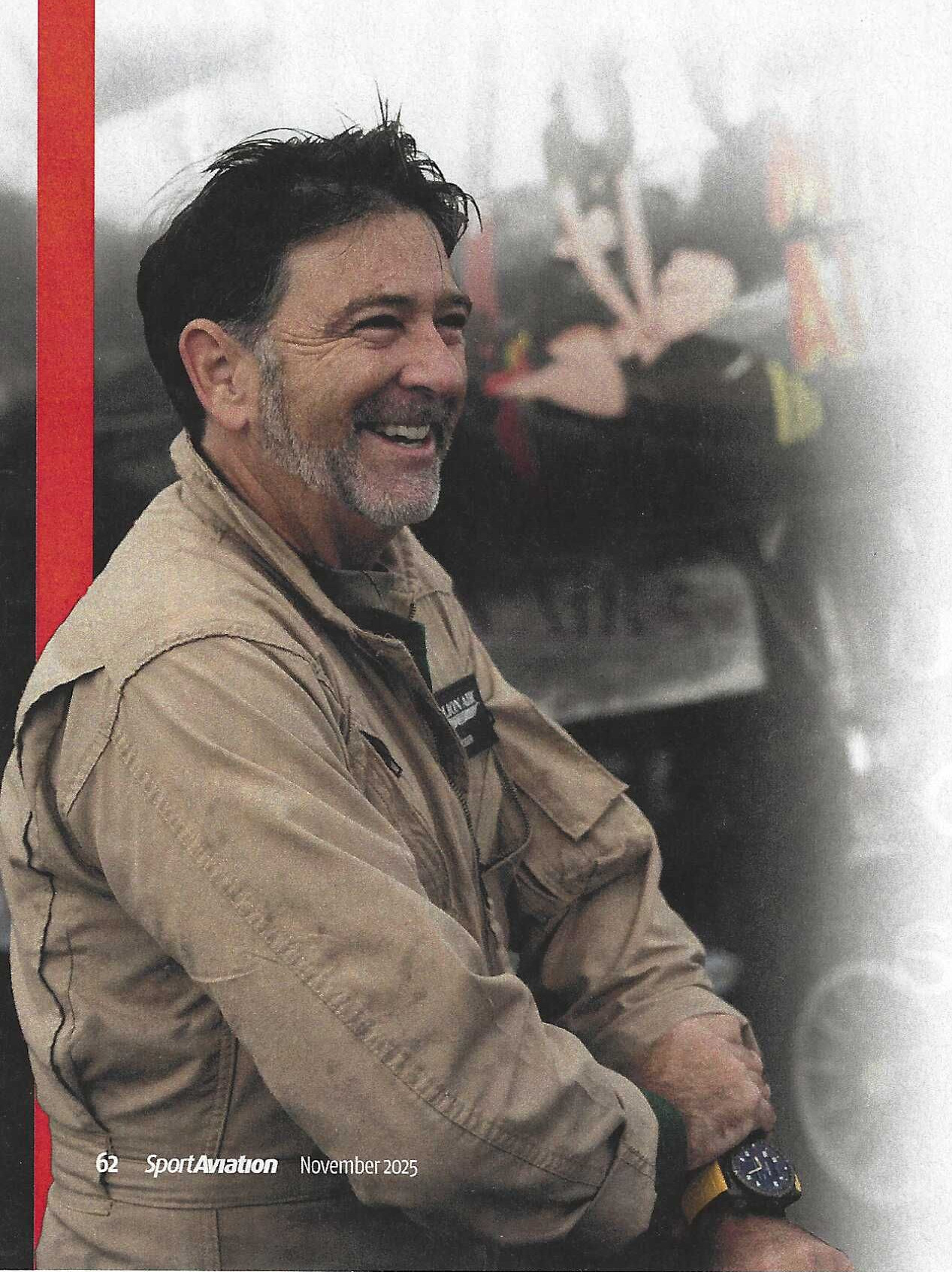

Roger Woolsey, EAA 1285100, has been a pilot basically his entire life. By the time he was 18 years old, he already had his commercial certificate. Through a connection of his, specifically a gentleman whose house Roger helped care for, he got an opportunity most wannabe professional pilots could only dream of at that age.

“He called me one day and said, ‘Hey, did you ever get your ratings?’ I’m like, ‘Yes, sir,' ” Roger said. “Bada boom bada bing, he made a phone call for me, and three days later I was flying Stevie Nicks with Fleetwood Mac in their old ... Vickers Viscount. So, I was a whopping 18, 19-year-old co-pilot in a foreign-engineered

plane on a world tour of one of the top rock bands in the world. Well, it ends up Chuck, the gentleman that I used to care for his house, he was Eric Clapton and Julio Iglesias’ personal chief pilot. ... That was my start. So, I was flying bands, and they were leasing airplanes. They would hire me as a pilot, and I got in that niche.”

At the ripe age of 20, Roger started his first company, Prestige Touring, which catered specifically to the rock ’n’ roll music industry. A few years later, in 1991, he founded American Jet, which focused on transporting medical patients all across the country, including picking up and delivering organs.

During that time, Roger was unhappy with the FBO {fixed-base operator} he was using. They consistently pulled his airplane out of the hangar late and didn’t seem to care about service. It was then that he started his own FBO, becoming a Million Air franchisee. Originally founded by the Mary Kay Cosmetics family, Roger soon became frustrated with Million Air as a brand and was ready to quit until a new opportunity arose.

“I went to tell [Mary] why I was leaving the brand and the family,” he said. “She’s like, ‘You know what? That makes sense. You need to go fix it’ I’m like, ‘I don’t have time to fix it. I’m going to go run my own brand, She’s like, ‘No, no, no, no, no. Here, go fix Million Air’ So, 30 days later, I owned the Million Air brand as a franchisor, and I had one company-owned store in several locations. That was in, I guess, early 2000s. So, here we are, 20 years later, and we’re in 38 locations.”

It was a few years after taking over Million Air that Roger first came across the airplane that, years later, would become Miss Million Airess.

41-39359

First flying in July 1942, the Douglas-designed twin-engine A-26 Invader was used during World War II for a few different mission sets, including level bombing, ground strafing, and rocket attacks. While the Invader didn’t enter service with the U.S. Army Air Forces until late in the war, first seeing action over Europe in November 1944, it proved its value until the end of the conflict.

When production halted, just over 2,500 A-26s had been built. Redesignated the B-26 in 1948, the Invader went to war in Korea as well, playing a key role in the interdiction campaign against the ground forces of North Korea and China. Finally, with the onset of war in Southeast Asia in the 1960s, the Air Force again called on the services of the Invader, with 40 B-26Bs modified with more powerful engines and increased structural strength, designated B-26K, to perform special operations missions.

Built by Douglas as an A-26B-30-DL and converted to an A-26C (with a transparent “bombardier nose”) shortly thereafter, Miss Million Airess, serial No. 41-39359, served with the U.S. Army Air Forces through WWII (notably flying during the Battle of the Bulge) and the Korean War before retirement in 1956.

After sitting at Davis-Monthan Air Force Base in Arizona for about a decade, a corporation in Chico, California, purchased it in 1966. It was used as an aerial firefighter with Conair Aviation in Abbotsford, British Columbia, beginning in 1967. Conair sold 41-39359 in 1987, and the airplane changed hands multiple times over

the next few decades, going from Planes of Fame East in Eden Prairie, Minnesota, to Palm Springs Air Museum in Palm Springs, California, to the Vietnam War Flight Museum in Houston. When Roger first spotted the airplane, he knew he wanted to fly it.

“I remember walking in, and I said, ‘Why are you guys not flying this airplane? Why are you not doing something with it?’ The museum was a very small boutique museum, and they said, ‘Well, quite honestly, the volunteers, the money.’ So, I made a proposal,” Roger said. “I said, ‘Hey, what if I sponsored this airplane? Would you let me fly it?’ They said, ‘Absolutely’ So, of course, I am not wealthy, but I threw what I had at it. We got it flying, and this was like 15, 16 years ago. I took it that summer to 28 air shows. I was never paid for an air show. I would say only five of them even gave me gas. I did it for the love of the aircraft, and it doesn’t hurt to promote Million Air at the same time.”

Shortly thereafter, the airplane was sold. With no idea a sale was in the works, Roger was pretty heartbroken about the entire situation. Fast-forward to May 2024. In a twist of fate, Roger spotted the Vietnam War Flight Museum’s executive owner at his Million Air FBO at Hobby airport in Houston.

“He saw me, and he says, ‘Hey, by the way, we got that A-26 back. Do you want to do something again?’ I looked at him, and I’m like, ‘It is like you raise a foster kid, and then they rip them out of your home. You know what I mean? Yeah, I’d love to do something, but I didn’t know museums sold things. You got to know it hurt my feelings last time. So, I’ll buy it, but I don’t want to sponsor it.’ Before I could finish pouring my coffee, he said, ‘Okay, we’ll sell it

to you.' I was in shock. I did not expect that. I wasn’t looking for a warbird to buy, but I was so in love with it 15 years ago when I was involved. I couldn’t believe it. So, I literally went home on May 10 and thought about it. I came back on May 11, and I said, ‘I’ll do it. Do you think she could fly and make it across to D-Day, to Normandy?' ”

Preparing for the Journey

Getting Miss Million Airess ready for a flight across the Atlantic was easier said than done, especially in the limited amount of time Roger and his team had to do it. With the 80th anniversary of the D-Day landings quickly approaching on June 6, it took a monumental effort to prepare the airplane.

It hadn’t flown much for the past decade or so. Roger called in a radial engine expert to see if it could be ready to fly by June. The expert estimated it would take three full months, meaning Normandy was out of the question. That wasn’t the answer Roger wanted to hear. He simply decided not to accept it.

“I just pulled everybody in, and I just thought, ‘This is my man on the moon moment for us as a company, as Million Air, a team of mechanics,' ” he said. “I gathered them all together, and I said, ‘Are we going to do this?’ They’re like, ‘Well, I think ..' No, no, no, no, no. ‘I think’ and ‘try’ are nothing but pre-excuses to failure. Are we going to make it? They said, ‘We'll do it' I said, ‘Okay, stack of hands’ We did. So, we literally put eight mechanics a shift, three shifts a day, 24

hours a day, seven days a week for three weeks. We worked on that airplane to get her back to life.”

In preparing Miss Million Airess for the trip, the Million Air team changed a bunch of leads and spark plugs on the engines, cleaned the carburetors, swapped every hydraulic line they could find, and installed a new Garmin radio stack, among other things. As a new player in the warbird community, Roger pointed out that he and his team couldn’t have gotten the airplane ready without the help and advice of others in the know.

“I’m so new at the warbird community, I didn’t know where to turn,” he said. “I love, love, love the warbird community.... I would call people. Rod Lewis, I mean, the guy’s running a multi-billion-dollar company. I’d text him, ‘Hey, I got a warbird question,' He would call me instantly. I mean, he would break out of a board meeting of his oil company to talk warbirds. I’m like, ‘Hey, I’m having trouble. I need a hydraulic pump, and I don’t know where to get one. They don’t make these anymore.' He would pull out his Rolodex of who is overhauling things and who’s got parts. It was a lot of work, but it’s amazing how the community held us up and helped us to make this mission possible.”

The team made a few test flights in late May. On Saturday, June 1, Roger and his crew pulled the airplane out of the hangar at 5 a.m., filled it with fuel, and began preparing to leave for Normandy, joined by many of their colleagues at Million Air.

“By 6 a.m., when I’m about ready to start the engines, I pulled my head up, and there were 40 employees around that airplane,”

Roger said. “You got to realize that these weren’t people working. This is their day off. I didn’t invite them necessarily for the departure. They just showed up because they wanted to be a part of it. I mean, that’s a testament to what these warbirds do to the hearts and souls. It gives meaning to our jobs. It gives meaning to our company and a mission.”

Bon Voyage

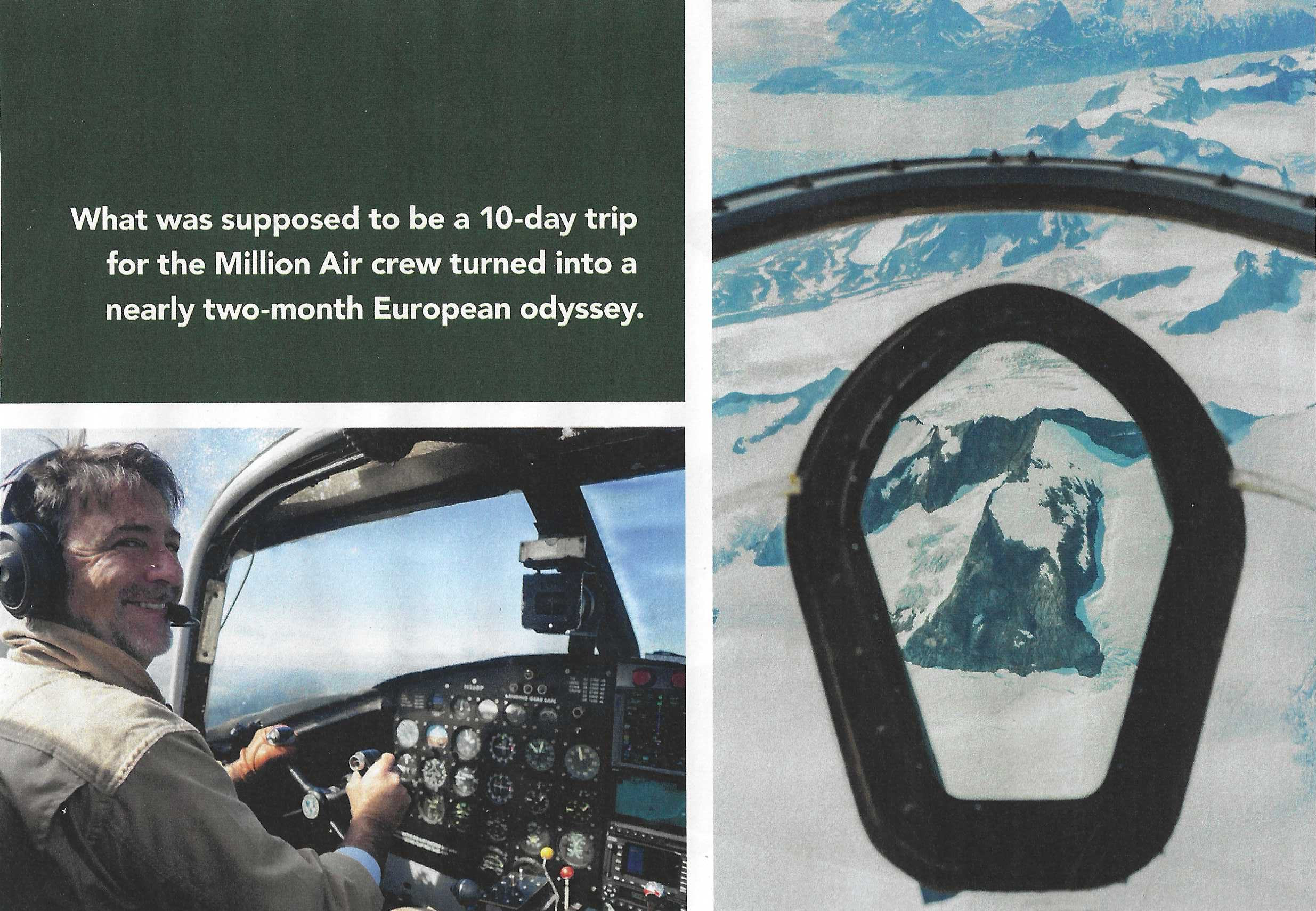

Starting from South Texas, Roger and his maintenance crew flew Miss Million Airess up to New England, into Newfoundland, Canada, and then followed the legendary Blue Spruce route across the North Atlantic—the same path so many aircraft took 80 years ago during WWII, with stops in Greenland, Iceland, and Scotland en route to Normandy. With such a quick turnaround from museum piece to flying airplane, the route to Europe certainly wasn’t without risks.

“We were passing broken-down DC-3s that didn’t make it,” Roger said. “I mean, every landing doing that Blue Spruce, I was in shock. I can’t believe we made another leg. Because I mean, inside of me, I was thinking we won’t make it. But on the outside of me, being the CEO and the leader, I’m like, ‘Come on, guys, we can do this.' I’m sure George Washington was shaking inside of his boots, crossing the [Delaware] that day, but you can’t show it.”

Despite what must have felt like overwhelming odds weeks before, Miss Million Airess made it to the beaches of Normandy for the 80th anniversary of the D-Day landings. During the commemoration ceremony, Roger and his crew had the incredibly special opportunity to meet Casey, a veteran of the Battle of the Bulge.

They wheeled Casey out to the aircraft, with 40 or so people around. Roger said it was something to behold.

“Everybody was just quiet,” he said. “You could hear a pin drop.... I still remember one of the things he asked me. He says, ‘Do you know what you’re doing with this?’ I’m like, ‘No, sir’? He says, ‘Yeah, you’re my guy’ But he was telling us stories about the airplane and what it was like when he was on the ground and the airplanes were coming over. He said, ‘Man, we cheered so loud on the ground when you boys flew over.’ He was talking to me like I was one of the soldiers.”

Eventually Casey wanted to get up close to Miss Million Airess, and he wasn’t going to be using the assistance of a wheelchair.

“He goes, ‘I’m getting out of this chair, goddamn it.’ They all stood back and in shock. It took him a good 10, 15 seconds to go from a sitting position to standing. He didn’t want help. He wanted to stand,” Roger said. “He pushed himself up, and he was probably 15 feet away from the airplane at that point. He got to the same position. So, then the CEO of United got on one arm, his handler on the other arm. They walked him up to the aircraft, and he put his hand up and touched the airplane. He started to cry. Forty people around the airplane started bawling. I mean, there wasn’t a dry eye.”

Roger said he couldn’t quite describe it.

“You just felt their sacrifice.... They keep talking about the Greatest Generation, and you just felt it. It was important. The man had so much honor. So, there was so much patriotism or he’s a hero. You know what I mean? Again, it’s that experience that’s

worth a thousand pictures. I wish I could describe it. I wish I could describe it.”

A Whirlwind Tour

While the sole purpose for the trans-Atlantic journey to Normandy was for the 80th anniversary commemoration of the D-Day landings, it’s not often European warbird enthusiasts have the opportunity to see a flying A-26. What was supposed to be a 10-day trip for the Million Air crew turned into a nearly two-month European odyssey.

“I feel lucky I’m still married because what happened,” Roger said. “I was supposed to be home on June 10. I called my wife, and I said, ‘Hey, these guys want us to come to Warsaw for an air show.’ She’s like, ‘What?’ I said, ‘No, no, it’s just going to be a couple of extra days.’ Then from there, Berlin. ‘Baby, now we’re going to go to Berlin and then Belgium, My wife at one point said, ‘Stop calling me, lying to me that you’re coming home in two more days.' ”

During the course of the Million Air team’s tour through Europe, which saw the airplane go to Poland, Germany, Austria, and Belgium, Roger pointed out that there were numerous times where the stars seemed to align in their favor when something unfortunate did happen.

For example, when performing during the air show in Warsaw, a fuel line in the left engine ruptured, and Roger feared the airplane may be stuck there for a while. Who would have a replacement fuel line for a 1942 A-26 in Warsaw, Poland? The answer: a local MiG-15 pilot, of course.

“This MiG pilot goes, ‘I want to fly with you, and I think I have that in my hangar,' I’m like, ‘You don’t have this in your hangar. This is an American-made WWII [airplane]. You’re a Russian MiG guy,' ” Roger said. “No, no, no, no. I have in my hangar. I go get it. I want a flight with you today. Thank you.' But I’m thinking, I just got grounded in Warsaw, and the guy takes off in his MiG. I didn’t know when he was going to his hangar. He meant he had to go fly to his hangar, but he flew over and sent his MiG. I’m not lying to you. One hour later, the guy lands, and as he’s taxiing by, he opens the canopy and he’s fisting these fuel lines like he got them. He walks up to the plane, and I am in shock they actually fit the airplane.”

A bit later, Roger and crew flew Miss Million Airess to Salzburg, Austria, home to Hangar-7 and The Flying Bulls, Red Bull’s collection of historic and modern display aircraft. After landing, a Red Bull mechanic was examining the airplane and noticed a major problem with the airplane’s brake pucks. That was something Roger was concerned about throughout the trip as he and his team were unable to find the brake pads they needed for the airplane in the United States. Again, a solution appeared out of thin air.

“Red Bull guy walks up and says, ‘Well, let me see. Maybe I have some of these.’ I looked at him again, and I started laughing,” Roger said. “I said, ‘Sir, you don’t have these. We have called everywhere in the world looking for A-26 brakes, and you don’t have these.’ He goes, ‘Well, hang on.' He comes back 15 minutes later and he says, ‘You have converted your brake system to the DC-6 brake system. I happen to own every brake in the world.' ”

As The Flying Bulls operate a Douglas DC-6B, their mechanic team scoured the planet for any remaining brakes and secured what

they believed to be the last case of them. And they just so happened to be a perfect match for Miss Million Airess.

“The one place I break down, he happens to have the only supply on the planet of these brakes, and I couldn’t believe it," Roger said. “So, now Red Bull jacks up my airplane. The Red Bull mechanics did it, and they replaced my brakes. I got brand-new brake pads. Just shocking.”

Then, they finally began the return trip to North America. When they were en route to Duxford, England, the right engine on Miss Million Airess started popping. As Roger explained, he’d never been to the warbird haven known as Duxford and didn’t really know what to expect. But, once more, it turns out they couldn’t have been in a better place at a better time.

The Duxford-based Aircraft Restoration Co. took a look at the engine and determined it needed a new magneto. While waiting on a magneto to be shipped from the United States, fate stepped in.

“There’s this pilot on the B-17 [at Duxford], and he says, ‘I know where there’s a case of parts in a barn,” Roger said. “Of course, we’re laughing at him.... He goes, ‘No, no, no, no. I think I got this in a barn. Follow me, I’ll take you.’ So, of course, we all pile in our car, and we start following this pilot, not knowing where we’re going. The guy drove for an hour and a half. I mean, the barn wasn’t down the street. I don’t know where in the hell we went, but we were going down dirt roads and there’s cows and there’s hay bales two stories tall, and we’re laughing our butts off at each other going, ‘This is either on Candid Camera, or I feel like we’re barnstormers. I mean, somebody’s going to punk us.' ”

Fortunately, Roger and his Million Air team were not on a hidden camera TV show. They struck gold again.

“We finally get to this old barn, and we have to move crap to get to this big a— wooden crate," he said. “We break it open with a crowbar, and the first thing laying on top is a B-17 tail wheel. We have to lift it

out of the way. Sure enough, here’s this wiring harness for an R-2800 and two of the GE magnetos. We just could not believe it. So, there we were finding these parts in a barn in the middle of England that’s been sitting there since 1944, and we take them out and we take them back to Aircraft Restoration Co. They crack them both open,

and they said, ‘Yeah, we can make one good one out of this,' and they did. They got Miss Million Airess back in the air. It was just shocking.”

Oshkosh!

As the Miss Million Airess rock ’n’ roll tour through Europe added additional impromptu stops, Roger kept one thing in the back of his mind—Oshkosh. He wanted to make sure he and the airplane were back in the United States by the time AirVenture rolled around in late July. But even then, you can forgive Roger if he wasn’t exactly prepared coming across the Atlantic and straight into the world’s largest air show.

“Oshkosh was also crazy,” he said. “We landed with not a lot of warning because I had forgotten to call and get a warbird parking spot. We had forgotten how hard it is to get an RV parking spot. You know what I mean? So, again, a little naive. But Oshkosh opened their arms to us.... We are very active with Miss Million Airess when we go to air shows. We really try to open her up. We’re there. We staff it. We don’t go away. We don’t have a rope up to keep people away from it. We let them come up and touch it and get oil on their shirt if they want.”

The crowd definitely wanted to see this aircraft up close.

“We had a crowd around that airplane from the moment they would let somebody onto the grass until the security guards were shoving people off at night,” Roger said. “We were exhausted at the end of every day. We’d lost our voices, all of us, because we’re telling the stories, talking about it.”

During the week of AirVenture, a number of people approached Roger to let him know they saw him and the airplane at various places in Europe—Salzburg, Antwerp, Duxford. Included in that group was an Austrian air traffic controller who, just weeks earlier, had brought Miss Million Airess into Salzburg with a P-51 escort. “It’s Oshkosh,” Roger said.

As Roger has become more ingrained in the warbird community over the past couple years, he’s seen how important these aircraft are to not only preserving history but also inspiring a future generation of pilots.

“If you talk to any pilot that exists, like most military pilots, there’s only two places that caught them on fire,” he said. “Why did you become a pilot? They’re going to tell you an air show story, or they’re going to tell you how they were on a family trip and the pilot invited them to the cockpit. The problem is the pilots don’t invite anybody to cockpits anymore. They’re not allowed; they don’t do it.... We’re not spreading the love like we used to.”

Roger said he thinks it’s up to the general aviation folks.

“We’re picking up the load, and that’s why we got to get to these air shows and open these assets for people to touch and feel it," he said. “Because I hated history when I was a child in elementary school and junior high and high school. I’m being honest, I did. Now I cannot get enough, but it’s because [warbirds] bring it alive. It makes it real, and then you start realizing the significance of it.”

Sam Oleson, EAA 1244731, is EAA’s senior editor, contributing primarily to EAA’s print and digital publications, and loves studying aviation history. Email Sam at soleson@eaa.org.

MissFig01.jpg |

MissFig02.jpg |

MissFig03.jpg |

MissFig04.jpg |

MissFig05.jpg |

MissFig06.jpg |

MissFig07.jpg |

MissFig08.jpg |

MissFig09.jpg |

MissFig10.jpg |